Family

VVS’ approach to life and cricket was shaped by the values imparted by his parents and grandparents. The biggest credit for his rise goes to his sporting minded uncle Baba Krishna Mohan who spotted his talent and believed in his ability. His parents were service-minded physicians who wielded the stethoscope rather than the willow. Laxman was a brilliant student who topped the united Andhra in Science in Standard-10. A career in medicine beckoned, but his parents never stopped him from following his dreams after witnessing his dedication and respect for the game on and off the field. Millions of cricket fans would thank and salute such great parents for that decision. VVS recalls that his lowest test score was in Telugu, but when he was on song taking on that spin wizard Shane Warne, the wristy strokes that flowed from his bat were as sweet as Telugu verse! His parents and grandparents were deeply grounded in dharma and sense of seva, and these values were instilled in him very early. It is apparent from his writing that they remain the source of VVS’ strength and provided the guidance for his decisions on and off the field. Laxman touchingly recalls his grandfather: “My paternal grandfather, Shri Jagannath Shastry, was a Bhagavad Gita teacher, a scholarly and erudite man who exuded divinity and goodness. He was in hospital with a broken leg after a fall at home, and before leaving his mortal coil, called my father over one night. He embraced him tightly, almost going into a trance, and shouted ‘Vijayam, Vijayam, Vijayam’ followed by ‘Aham Brahmasmi, Aham Brahmasmi, Aham Brahmasmi’ before peacefully breathing his last. This was to make a lasting impression on my father, and he dedicated himself to the service of humanity from that moment on.” Before he became a test cricketer, his father spoke not of locking-in commercial endorsements or batting records, but to remind a young Laxman of his duty.“The profession doesn’t glorify you, you glorify the profession. We are serving Mother India through medicine, you serve her through cricket."Laxman recalls: “I knew even then that I would never forget those words.” Once, when Laxman was injured and thought it would be difficult to play in an important upcoming match that needed his presence, he recalls a conversation with his father who put things in perspective: “… he reminded me of the hardships our soldiers encounter on the borders—their pain and discomfort, the long months away from their families, the huge sacrifices for our safety. He urged me to overlook my body’s protestations and use the power of the mind to blank everything out.” On another occasion his father gifted him a book by Swami Vivekananda that put him in the right frame of mind to do his best for his team. Right from the start, we see not a materialistic path to fame and money, but a long term vision rooted in dharma to serve the nation by playing for the team rather than chase individual glory. Post-retirement, Laxman is involved in providing scholarships to deserving students and supporting service-minded organizations. VVS had sporting genes, but the values imparted by his parents made him a great team player and helped India become a team that could hold its own against the best. Laxman stands as a reminder that even in this modern, technology-driven world of professional team-sport, family support is irreplaceable.

Shraddha and Sadhana

Next, we learn how the Gita helped VVS in his journey. His positive words are sure to encourage youngsters to follow in his footsteps. “The Bhagavad Gita has been a strong source of inspiration and learning throughout my life. My paternal grandfather, who had a massive influence on me when I was growing up, familiarised my brother and me with the shlokas, patiently explaining to us what they meant. Chapter 12, Bhakti Yoga, speaks of, among other things, giving one’s best every single time and not worrying about the results; remaining equanimous in victory and defeat, in success and failure. I took these principles to heart from when I was 17.” Many of us have read the Gita but end up merely intellectualizing it. In VVS, we find a person who has actually applied the teachings of the Gita in practice, in those difficult days of being in and out the team (especially the 2003 World Cup), and in those final hours and minutes of a test match when he was at the crease and India on the brink of defeat: “As I grew older, I realised that the origins of many of today’s success mantras lie in the scriptures. Especially, but not exclusively, from a cricketing perspective—focusing on the process and not worrying about the result. The results take care of themselves if you do the processes right. That’s precisely what the Gita says—do your duty, but not with an eye on the outcome. Effectively, it means the only thing that is in your hands is the effort. That is what drove me—the desire to not leave anything out when it came to effort…… I recalled the essence of the Gita—nishkama karma, reposing your faith in Lord Krishna and doing your job without worrying about the outcome. I could feel the confidence return.”

It is apparent that the sacred Puja room and the stadium of the material world were not two independent realities but an integral and seamless domain for Laxman. His team-mates mention how his half of the hotel room that they shared resembled a mini-temple! Seeking the blessings of Shirdi Sai Baba was something that he would repeat on several occasions, and this often preceded amazing performances. It is worth noting from the book that Laxman never went there to ‘petition for a century’. He talks of attaining a higher state of equanimity and peace of mind that enabled him to give his best. This Shraddha and Sadhana [4] that comes out of one’s own experience was central to VVS’ preparations since childhood, and to which he credits his poise in the face of adversity, self-doubt, and uncertainty (after all, cricket has been called the game of glorious uncertainties).Karma

VVS recalls his visit to Shirdi before that fateful Kolkata test in 2001. Australia had trampled over India in the previous test in Mumbai. Rahul Dravid was down with viral fever. Laxman suffered a slipped disc and was tearfully unsure if he would even be in the playing eleven. Then the first half of the match was a total disaster for India, and the second innings did not start well either. Half the Kolkata crowd had departed when Rahul joined Laxman at the crease that day. As Laxman notes elsewhere in the book, they were among the last generation of batsmen who played not for runs but for time. Hour by hour, the duo gradually brought India back from the brink. Many would agree that their partnership ended up changing the mindset of Indian test cricket."The more I look back at the Eden Test, the more my belief in fate and destiny is strengthened". - VVS Laxman.During the ongoing India-Australia test series (2018, Adelaide, Test-1,Day-5) commentary, an Aussie TV commentator mentioned that the Indians were more superstitious than all other international teams. Harsha Bhogle not only did not reject this claim but suggested that this was because ‘Indians were fatalistic’. As Rajiv Malhotra has explained [4], “Karma, contrary to Western misconception, is not fatalism in the sense of an external force depriving humans of free will. This misunderstanding has significantly distorted the West’s understanding of dharmic civilization. In truth, the principle of karma is a constant challenge to act without attachment to the fruits.” Perhaps Mr Bhogle needs to talk to Laxman garu and learn how Karma works so that he does not misrepresent dharma tradition in front of a live audience. VVS Laxman’s understanding of such concepts in the book is positive and inspiring, and his attitude is anything but ‘fatalistic’, having brought team-India back from the dead many times! There is not a trace of ‘superstition’ in his visits to Shirdi and Mandirs and his application of the Gita’s message of acting without eyeing the outcome are beautifully in sync with Rajiv ji’s explanation. These paragraphs in the book also show that Laxman was able to retain his adhyatmic/embodied knowledge [4] as the foundation while supplementing it with the information gained from the instrumentation-driven modern sports sciences (bio mechanics, sports medicine, nutrition, etc.). We have seen attempts to implement this ‘formula’, albeit in a digested form, in the NBA (Phil Jackson and the legendary Chicago Bulls), and the NFL (New York Giants). While modern instrumentation and laboratory testing can provide a material explanation for ‘what is going on’ with a high level of precision and ‘quantify’ these findings, the answers to deeper questions like ‘how can I improve my mindset’ come from the inner sciences of India’s traditional knowledge systems. We briefly study two examples from the book in this context– Laxman’s ability to raise his game in a pressure situation (where time is counted in hours and minutes), and his ability to ‘time’ the ball (where time is counted in fractions of a second).

Mr Comeback Man: Grace under pressure

Coming in at #6 in the latter half of his career, Laxman was often the last man standing — the Vivekananda rock who could turn near-certain defeat for India into victory (World-cup winning India coach Gary Kirsten labeled him Mr. Comeback man, the ‘Michael Bevan of test cricket’). In a pressure situation, in front of a huge live audience, a batsman has nowhere to hide – he can choke, perform as usual, or even deliver above par (Laxman talks about entering a ‘zone’ where everything is in harmony). VVS was able to execute his skills in pressure situations like few other players could. How does one retain focus when the going gets tough? First, Laxman talks about remaining focused in preparation and doing things right without becoming obsessive in trying to control the outcome (the teachings of Gita applied beautifully): “[Cricket] is also a game that is played between the ears. The more relaxed and focused you are, the better are your chances of succeeding.” “There is a very thin line between being focused and being obsessed. The former entails attention to detail during preparation, reading the pitch and the opposition bowling, being ready for any eventuality, and feeling confident that you have done everything within your means to give yourself the best shot at scoring runs. The latter is all-consuming and takes your mind away from the larger picture, from the process, as it were. If all you are thinking about is the outcome, the processes get skewed”. Next, VVS explains how he applied this mental approach to derive a working formula for batting in high pressure test cricket: “.. I had worked out a formula for batting under pressure. It involved acceptance and understanding, to start with… It was important not to panic. My solution was to break the end goal into smaller targets. When we achieved little milestones, the bigger objective automatically took care of itself. For this, I had to be in sync with my partner, so the communication had to be straightforward and clear. I also had to accept that while there was pressure, I would follow my routine. If you lose patience, you are bound to make mistakes. If you remain patient for long periods, the opposition will try something different. That’s when you must cash in, but without ever becoming complacent because there is still a job to be done. This is not a formula that comes with an always-win guarantee, but it worked for me more often than not.” Here we find the ancient Indian Ganita idea of ‘Kuttaka’ (to break a bigger problem down into sub-tasks) that remains a fundamental approach to solving complicated problems. Implicit in the formula is the dharma of collaboration, sahakarana dharma, which includes mutual trust between team members. VVS often batted with #10 and #11 who were bowlers and not recognized batsmen. Here, Sanjay Manjrekar and Rahul Dravid talk about this ability and the sense of reassurance he brought to his team. We also find the most difficult quality of all to master when every urge screams ‘break free and hit the panic button’ — patience, and the Indian quality of comfort with uncertainty and chaos [4]. All these elements unite to implement the teachings of the Gita in order to best serve the team goal. VVS comes across as a modern-day pro who was able to practically combine the sacred inner sciences, the modern mind sciences (which we now know borrows heavily from the Indic traditions), and artistry to excel under pressure and often prevail. Sometimes we come across two cricketers, both blessed with supreme skill & dedication: One often chokes and panics under sustained stress, whereas the other invariably closes out the game and even in defeat, never defeats himself. Why? To answer this, let’s delve into the science underlying the art-form of batting under pressure.Why do we choke?

As many top cricketers have explained in TV interviews, the ability to ‘remain in the present’ and not panic is crucial during the key moments of a contest. In the book ‘Choke’ [1], Sian Beilock studies the mechanics of choking in not just sports, but also high stress situations such as a competitive academic test or a job interview. “Choking under pressure is poor performance that occurs in response to the perceived stress of a situation. Choking is not simply poor performance, however. Choking is suboptimal performance. It’s when you— or an individual athlete, actor, musician, or student— perform worse than expected given what you are capable of doing, and worse than what you have done in the past... … Choking can occur when people think too much about activities that are usually automatic… people also choke when they are not devoting enough attention to what they are doing and rely on simple or in correct routines… Choking is most noticeable when an opportunity to win is squandered, perhaps because this is when the pressure to excel is at its highest. Choking is not random.” Stress triggers worry, which consumes a chunk of the precious ‘working memory’ required to manage and execute a sequence of complex and time critical tasks that require us to piece together several pieces of information [1]. There are two types of memory at play here, which is restated below in a cricketing context:- Implicit memory: this is a procedural or unconscious memory that oversees the execution of the cricketer’s skills.

- Explicit memory: this helps us reason out things and recall prior events at a conscious level, e.g., the line & length a particular bowler tends to employ.

The Art and Science behind VVS’ Timing

Laxman was at his best against the top cricketing nation of Australia and elevated the art of batting to the highest level. Remarkably, he did not have to sacrifice his artistry to achieve results in tense contests. They were integral to his success since his strokes were not a synthetic add-on but a natural outcome of an ability to ‘time’ rather than bludgeon the red orb. In his book, VVS makes his genius look simple while explaining this to us mortal beings! “The way I see it, timing is how the ball flows off your bat. The masters of timing are able to strike the ball from the sweet part of the bat more often than not because they ‘see’ the ball a fraction of a second earlier than the rest. Picking up the length stems from the cues the batsman garners—the way the bowler is running in and the position of his wrist at delivery. The sooner you pick up the length, the more time you have to play your shots—by more time, I am still only talking fractions of a second. There is a subtle correlation between time to play your shots and timing. The latter effectively means imparting maximum power to your strokes without trying to hit the ball too hard”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2-zkRgqYZbs Imagine Brett Lee at his peak, bowling at 90-95 mph. This is about 44-46 yards per second, and the ball takes 400-500 milliseconds to traverse a 22-yard cricket pitch (and slightly lesser time to reach the batsman). Somehow, VVS is able to ‘see’, prepare and decide, and get into a perfect position to pull the ball to the midwicket boundary using sheer timing. The number of milliseconds involved in this process is one of the reasons that makes cricket a special sport. Frank Partnoy’s book on the art and science of delay [2] explains the difference between superfast sports like cricket and the merely fast. “Football, soccer, and basketball are played in seconds; tennis, baseball, and cricket are played in milliseconds… Incredibly, the best athletes are able to observe their opponents, process information about their opponents’ actions, and then react, all in a few hundred milliseconds.… Superfast sports tap into the most primal, survivalist parts of our nervous systems. They mimic a fight to the death, a civilized version of a pistol duel… It is designed for periods longer than the fastest visual reaction time but shorter than the minimum conscious reaction time.” Well of course, MS Dhoni took this duel analogy to its logical end and made it a nerve-wracking one-on-one contest, and backed his ability to prevail in this contest of the milliseconds. Partnoy cites the finding of University of California physiology professor Benjamin Libet regarding this time interval that lasts more than 200 ms but less than a second: “[there is] a consistent half-second delay between a person’s unconscious reaction to a stimulus and his or her conscious awareness of the stimulus. Libet found that we don’t become aware of a reaction—even our own reactions—for half a second.” Recalling Beilock’s discussion, we can recognize the role played by implicit memory and pre-conscious reactions while batting. When we choke, this response and timing can get messed up. The ~500 ms decision time available is such that a professional batsman’s response is neither purely reflexive nor conscious. Interestingly, if a cricket pitch was shorter or longer than 22 yards, then cricket would’ve been a whole different ballgame [2]. Next, Partnoy learns about a key factor that differentiates the best professionals from an amateur cricketer: “Laboratory studies of baseball and cricket confirm that the best professionals are better, not because of what they do during the “see” phase, but because of what they do during the “prepare” phase.… it was what batters did after their visual reaction that distinguished professionals from amateurs… The professionals were quicker, but not by much—just in the range of tens of milliseconds quicker.” Per Partnoy, what makes the timing of a top pro like Laxman special is the “ability to create extra time, and then get the most out of it, before they have to react. They expand the available time period, slow it down, gather more information, and then end up in the right place to hit the ball … They are delay artists…” These laboratory research findings sync nicely with Laxman’s discussion of timing derived from his own experience. Instead of the quickest response, the pros actually ‘play the ball late’, as the TV commentators exclaim. It looks easy on TV, but a whole lot of high-speed cricketing Ganita and guts are required to pull it off!A Brief Story about ‘Delay’

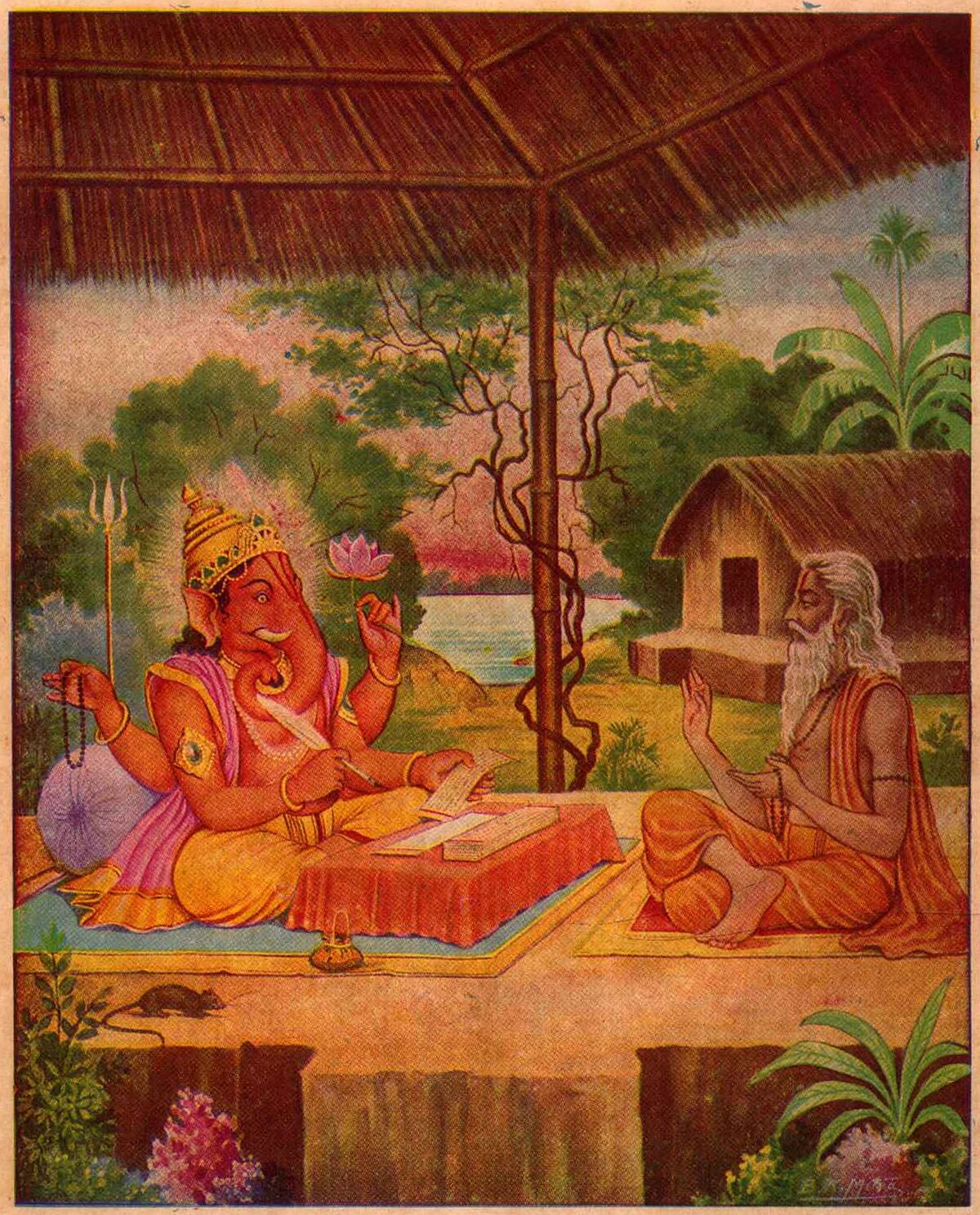

The story in our Itihasa of Sri Ganesha as Veda Vyasa’s amanuensis can also be used to explain the benefit of ‘delay’. We learn that Vinayaka gives himself an extra bit of time to grasp the full range of meaning of each verse of the Mahabharata before writing it down. This delay is equally beneficial to Veda Vyasa to prepare the next few verses rich in depth and meaning before speaking, thereby renewing this process. This dynamic equilibrium produces an uninterrupted and transparent flow of sacred verse. The spoken words of the Rishi continually pour into the divine script of Mahaganapati, resulting in an integral unbroken composition. By Gita Press Gorakhpur – https://archive.org/details/SankshiptaMahabharatPart1GitaPressGorakhpur, CC0, Link

Delaying decision making sufficiently (not unnecessarily) to identify a best response is critical to modern AI-driven decision optimization systems. In fact this approach is useful to all of us when we have to take important decisions within a short time limit. Students taking a competitive entrance examination or candidates attending a job interview may choke under the burden of expectation and end up answering too quickly or simply freeze. It may be better to expend additional time to fully grasp the nuances of the question, and then proceed to crisply answer. Also, one has to repeatedly practice this approach in mildly stressful ‘training conditions’ [1]. Partnoy also mentions the use of Yoga and meditation (that originated in the dharma traditions of India), which can helpful in this process.

By Gita Press Gorakhpur – https://archive.org/details/SankshiptaMahabharatPart1GitaPressGorakhpur, CC0, Link

Delaying decision making sufficiently (not unnecessarily) to identify a best response is critical to modern AI-driven decision optimization systems. In fact this approach is useful to all of us when we have to take important decisions within a short time limit. Students taking a competitive entrance examination or candidates attending a job interview may choke under the burden of expectation and end up answering too quickly or simply freeze. It may be better to expend additional time to fully grasp the nuances of the question, and then proceed to crisply answer. Also, one has to repeatedly practice this approach in mildly stressful ‘training conditions’ [1]. Partnoy also mentions the use of Yoga and meditation (that originated in the dharma traditions of India), which can helpful in this process.

Takeaways

One need not follow dharma traditions to become a top sports pro. However, embracing Hindu culture’s integral approach to life makes us better humans and wiser decision makers. Harmony in career and relationships is naturally achieved in this process of following the four Purusharthas. Fortunate are those who realize this open secret early in their life and act upon it. On the other hand, an absence of clarity can result in a person carrying a duality of objectives in their head. In the heat of battle, this ambiguity leads to confusion, negativity, loss of trust between team-members, and a degradation in the quality of decisions made. It was wonderful to learn how Laxman’s mental strength and team spirit played its part in taking India to the #1 spot in the test rankings. The book is aptly titled ‘281 and Beyond’ for its narrative goes far beyond a single magical innings. The ideas shared by Laxman in this book transcend sport, and are a celebration of a dharmic way of life that has sustained India for ages. Thanks to VVS Laxman for give us fans so much joy with his batting and for writing this inspiring book.Click here to Buy this Book!!!

References:

- Sian Beilock. Choke. Simon & Schuster, Inc. 2011.

- Frank Partnoy. Wait: The Art and Science of Delay. Public Affairs. 2013.

- VVS Laxman. 281 and Beyond. With R Kaushik. Westland Sport. 2018.

- Rajiv Malhotra. Being Different: India’s Challenge to Western Universalism. Harper Collins. 2011.