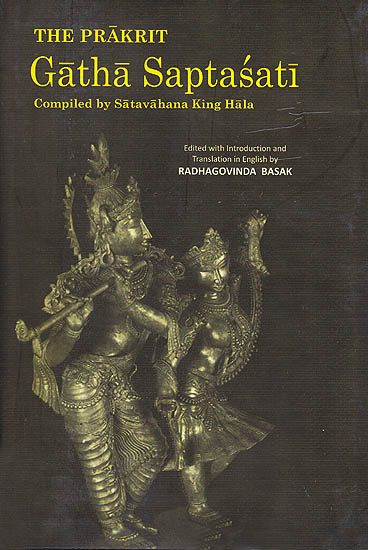

Having previously commenced our study of Classical Indic Literature, we now take our first look at Classical Indic Poetry. Appropriately, our first selection is from Andhra itself and dates back to the glorious Empire of the Satavahanas. This great dynasty featured mighty Conquerors such as Gautamiputra Satakarni and is famed for the Art & Architecture of Amaravati. However, it also produced talented poets such as Hala, an earlier dynast. He was the compiler of and contributor to the Poetic Anthology Gathasaptasati (known as Gaha Sattasai in the Maharashtri Prakrit in which it is composed).

Translated into many Indian, European, and Middle Eastern languages, the Sapta sati (also known as Gaha koso—or ‘Treasury of Gathas’) is considered to be one of the earliest surviving anthologies of Classical Indic Poetry.

Composition

While Sanskrit reads in an highly refined and courtly fashion, Prakrit is far more bucolic and earthy, fitting for the red earth of the Krishna-Godavari. Indeed, if Sanskrit literally means “refined”, Prakrit literally means “natural” and “common”. As such, while composed by none other than a great king, this work is appropriately written from the common woman’s perspective. Indeed, it is a fitting riposte to all those who seek to brand Classical Indic Literature as “elitist” and disconnected from the masses. Rather, it intimates a close awareness and love for village life and the village itself. While it is indeed Love Poetry, it is as much an ode to the Dakshinapatha (Deccan), its rivers, its plant life, and its rural life. Gardens, assorted flowers, maidens, ploughmen, hunters, and sisters are all mentioned and appreciated. Indeed, it is a celebration of the common life. From festivals, to bucolic happenings, to sylvan hideaways, to the qualities of good men and good women, we are given a a snapshot of the time.

Replete with imagery, the Godavari River itself is treated by the Gathasaptasati as a metaphor for the flow of love and desire. The banks of the nadi are viewed as a near aphrodisiac. It has, with good reason, been called “a woman’s book, a compendium of her gestures, utterances and silences“. [1]

Foreign commentators have had a tendency to over-emphasise the wanton and libertine while ignoring the loyal and chaste. Here is counter-evidence to their claims:

“house-wives entreat people going to the places of work of their husbands, to ask their husbands to return home earlier, or if they are literate they themselves send to their husband love-letters with similar request.”[2, xvii]

“Even a wife of noble family used to keep in writing on a wall of her house the last promised day of return to her husband (2.70). Such a lady often repeats many a time the words of her husband sent to her through a messenger (2.98)” [2, xix]

“In this way we come across many a passage suggestive of deep love on the part of husband & the wife” [2, xvii]

There is a full spectrum to love, and Sringara-kavya necessarily will cover both the negative and the positive. While it is true, in general, classical poets for the sake of auspiciousness (mangalam), prefer to focus on successful and faithful lovers, Haala gives us a full picture of the society, any society. The gossipy and guilty village-woman, the youthful ploughman, and the faithful wife and husband, all are captured here in verse.

Contrary to modern characterisations, kavya literature is neither uniformly prudish nor prurient. It very much runs the gamut, as do Hala’s 700 single verse poems (Sapta – satti), in Gatha form (the Prakrit counterpart to the Sanskrit Sloka and the Apabramsha Doha). Satakas are famous in Telugu literature, and the pre-Literary Telugu period of the Andhras was no different. A gatha, or song, consists of as many as 27 different variations, but is generally structured with 30 matras (syllabic instants) in the first line, and 27 in the second line. It is composed in the traditional Arya meter.

Elsewhere a prakrit gatha is defined as:

Pathamam vaaraha mattaa veeae atthaaraehi samjuttaa |

jaha patamam taha teeam dapancha-vihoosiyaa gaahaa ||

“That is called a gaaha or gaathaa which contains twelve maatraas in the first foot, eighteen in the second, again twelve in the third & fifteen decorating it in the fourth.” [2,ix]

The Kashmiri literary theorist, Anandavardhana wrote on the importance of dhvani, or resonance, in his suitably titled Dhvanyaloka. According to him, the gatha is the poetic embodiment of dhvani, and he himself was a poet in Prakrit. Indeed, in contrast to the ornamental and elegant Sanskrit of Kalidasa, the Prakrit of Hala et al truly resonates in unadorned yet evocative form. Simple, quick, and powerful.

Filled with vyanjanaa (suggestiveness), it is a work that appeals to the reader not only with sentiment, but with resonant simplicity. Earthy yet profound, rustic yet refined, it is redolent with the full spectrum of romance. At times insightful, at times humourous, at times chiding, and at times ennobling, it is a complete work. 262 authors are thought to have contributed (including 7 women). The Emperor Hala himself is credited with 44 of the 398 slokas. The colophon of each century of poems ends as follows:

Here ends the [first] century of gaathas from amongst the seven centuries, composed by good poets headed by Kavivatsala, which are so dear to the heart of men of taste (or sentiment). [2,23]

Writers such as Abhinavagupta (Kashmiri commentator), Kuntala (Vakrokti), Mahimabhatta (Vyaktiviveka), and Mammata, the author of the Kavyaprakasa, and others, have all cited this famed poem as examples for their theory. [2, x]. The Bana himself said the following, ostensibly in reference to Hala:

Avinaasinam-agraamyyam-akarot Saatavaahanah|

visuddha-jaatibhih kosam ratnair-iva subhaasithaih||

Just as (a king) collects a treasure which is inexhaustible and worthy of use by refined people, by means of jewels of pure kind, so the Saatavaahan (King) prepared an anthology which is imperishable and un-vulgar, by means of apposite sayings, which abound in pure jaati or Svabhaavikti alamkaara. [2, xi]

The sthayibhava and rasa are undoubtedly Rati and Sringara respectively. The anthology records every day trials and tribulations of Love and the Erotic, as well as the ebb and flow of affection. Indeed, it describes the escapades of various lovers and how they seek each others forgiveness, while others remain loyal. As described in our previous post, merely because the masses fall short of the ideal, should not mean that people should refrain from aspiring to them. Many of the descriptions are indeed erotic, touching on both the romantic and physical nature of love in real life. The poem itself exhorts virtue in those who seek to attract a beloved.

It is by dint of virtues that a (female) person obtains a (male) person who is worthy of being seen with unsatiated looks, who is equally affected

(with his beloved) in weal and woe, who offers good disposition and who is mutually attached to the heart (99) [2, 23]

Author

Not much is known about Emperor Hala (pronounced Haala). According to Western archaeology he is tentatively dated to between 200 BCE and 200 CE (but likely much earlier according to the indigenous Indic Chronology). The 17th Satavahana dynast in the pauranic king lists, Hala himself is called Kavi-vatsala (‘he who has parental affection for poets‘). Considered to be religious, he is famous for his patronage of Prakrit over the more popular and elite Sanskrit of the time. Despite this, the influence of his anthology extended to poets centuries after him, such as Govardhana, who wrote the Sanskrit work, Aryasaptasati . He is mentioned by many other Pan-India litterateurs such as Bana of Harsacarita fame.

Maharashtri Prakrit was considered the finest of all Prakrits, and is appropriately used in this work and many other classical ones. Only a portion of the Gathasaptasati, 44 of the 700 verses, are attributed to the Satavahana Emperor. The remainder are said to have been collected from assorted poets, most anonymous. There were as many as 7 or 8 women poets in an estimated 261 total, truly making it the poetry of the people.

The selection below, however, gives a only a taste of rati bhava and focuses more on sringara rasa. Enjoy.

Selections

§

Pia-viraho aappia-damsanam aa guruaaien dho vi dukkhaien|

Jie tum karijjasi theeain namo aahijaaie||

Separated from the woman you love,

To sit beside one you do not is

To double your sorrow. I honour

The goodness that brings you. (24)

§

Adrisanena pemmam aaveai ai-damsanena vi aaveai|

Pisuna-jana-jimpaina vi aave ai aimeaa vi aave ai||

Distance destroys love,

So does the lack of it.

Gossip destroys love

And sometimes

It takes nothing

To destroy love. (81)

§

Bahu-pupaph-bharonamiaa-bhoomi-gaa-saaha sunasu vinnatthim|

Rolaa-tad-viaad-kudangam-mahuaa saniaam galijjaasu||

Oh Mahua

Blossomed

On Godavari’s

Arboured bank

Shed

Your flowers

One

After

One (103)

§

Sama-sokakh-paivadadiaanaum kaalena rooda-pemmaanaum|

Mihunaanaum marada jam tham khu jiaai aiaaram muaam ho ai||

Their love by long years secured,

Sharing each other’s joys and sorrows,

Of such two the first to go lives,

It’s the other, dies. (142)

§

Bahu-viha-vilaasa-rasiai surai mahilaanaun ko uvajjhaao|

Sikkhaee aasikkhiaaeen vi savvo nehaanu bandhena||

Bookish lovemaking

Is soon repetitive:

It’s the improvised style

Wins my heart. (274)

§

Rannaau thanam rannaau paaniaam savvaam saam-gaaham|

thaha vi maaun maeen aa aamarananthaaeen pemmaaeen||

Stag and doe

Enter the forest

Separately looking for

Herbage and water,

And stay unparted

Till death. (287)

§

Lajjaa chatthaa seelam aa khandaam aajasa-gosanaa dhinnaa|

Jassa kai nam piaa-sahi so ccheaa jano jano jaaao||

He, for whom I forsook

Shame, chastity, honour,

Now sees me as just

Another woman. (525)

§

Muha-pecchaao paee se saa vi hu savisesa-damsanumbaeeaa|

do vi kaatthaa puhaeen aamahila-purisam va mannannthi||

He looks deeply in her face;

She is sunk in his vision

Thus looking at each other in great joy

As if for them they were all alone in the world. (743)

§

It is available for Purchase today in Telugu and English editions:

References:

- Mehrotra, Arvind Krishna. The Absent Traveller: Prakrit Love Poetry from the Gathasaptasati of Satavahana Hala. Penguin: Delhi. 2008

- Basak, Radhagovinda. The Prakrit Gatha Saptasati. Kolkata: The Asiatic Society. 2010

- Peter Khoroche; Herman Tieken (2009), Poems on life and love in ancient India: Hāla’s Sattasaī

- Amaresh Datta (1988) Encyclopaedia of Indian literature vol. 2 Chennai: Sahitya Academy

-

Winternitz, Maurice. History of Indian Literature. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. 1985

* Numbering diverges from original. Done according to Albrecht Weber's German translation.