In a time of trial and tribulation, it is easy for one to turn to divination or inquiry amongst the stars. But those who make claim to wisdom and statecraft must be rooted in practical principles. It is not enough to cite Dharma at the turn of every incident, or demand massive action on the basis of singular criterion. In truth, the sapthaanga of statecraft are not static, but are moving parts, that are on the move—virtually all the time.

As such, equanimity and prudence is required in facing such difficulties. Indeed, prudence, prioritatisation, and proportionality are all too lacking not only in the actions of Bhaaratheeyas, but also in their speech. Bombasticity, bluster, and buffoonery remain their “brahmic” as well as “a-brahmic” calling cards. This behaviour is not unlike the sons of an ancient Indic King, who sought to refine their demeanour and dignify it with wisdom. Hence the Hitopadesa.

“The Hitopadesa belongs to the class of compositions which aim at teaching the principles of polity guided by morality as far as possible.” [2, v]

Literally meaning ‘Book of Good Counsel’ or Discourse on One’s Interest, Hithopadhesa does more than merely educate on good policy. It illustrates the when, the where, the who, the what, the why, and even the how, that politicians must ask before implementing policy. Rather than reactive, it is reflective and instrospective. The first rule of politics, after all, is knowing who is in the room before one speaks. Speaking the truth alone is not enough. Knowing when to speak, how to speak, why to speak, before whom to speak, and even what the implications of speech are, is something that bigmouths need to keep in mind.

Often conflated for the more copious Panchathanthra, the Hithopadhesa is a related text that self-admittedly draws from the source text, but repackages it in supple form for statecraft. In contrast to our contemporary kullu vidhvaanas, ancient Hindu scholars were honest in their attribution, giving credit when due, rather than staking claim to reinventing the wheel—constantly. The result is not an echo-chamber “ecosystem’, but an honest and civic, civil society that is capability of internal collaboration, rather than pathetic external collusion.

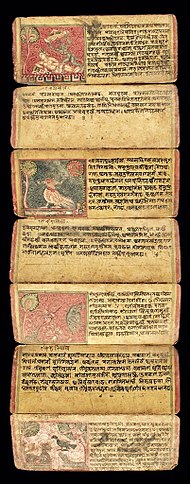

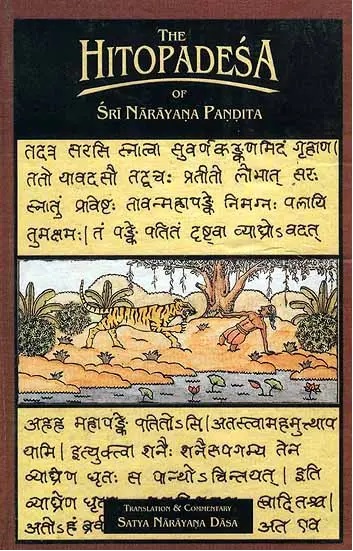

“The Hitopadesa is one of the best known and most widely translated works of Sanskrit literature. It is a collection of animal and human fables in prose, illustrated with numerous maxims and sayings in verse, both intended to impart instruction in worldly wisdom and the conduct of political affairs. Couched in simple and elegant language, it was also meant to provide a model for composition and rhetoric. These features made it a popular ‘reader’ for students of Sanskrit in India from ancient to recent times.” [1, x]

In an age of pedantry and navel-gazing, practicality is the need of the hour. Statesmen and policy-makers simply do not have the luxury of dhadhyannam-powered debates that drone on and on in pointless minutiae for ages. Statecraft is not for those who specialise in jalpa & vithanda vaadha. Even Tarka Sastra disqualifies such inapt people (anaapathas?). Specialisation is for those who actually practice, and proof of the pudding is in the eating.

“The work has also been placed in the Sanskrit literary genre of nidarsana kathaa or exemplum, a story which aims to teach by examples and is often satirical.”[1, xii]

“Naaraayana’s ‘another work’ covers multiple sources. Sternbach’s study categorizes them into three broad groups: neeti, dharmasaastra, and other miscellaneous works. The first two are reflected mainly in the verse portions of the Hitopadesa. Apart from the Pancatantra, Naaraayana’s single main source is the verse composition Neetisaara of Kaamandaki. Nearly ninety verses in the Hitopadesa are quotations from this work. Devoted chiefly to the aspects of neeti that deal with political theory, most of these verses are contained in the third and fourth books. They discuss the subjects of diplomacy, war and peace.” [1, xiii]

Above all, it must be remembered that despite its youthful appeal and zoological cast of characters, this is first and foremost a treatise on Neethisaasthra.

“The nature of the Hitopadesa is clearly defined in its prologue. The second verse names the work and asserts that its study gives knowledge of ‘neeti’, apart from proficiency in language. Subsequent verses extol the merits of learning and knowledge. The work is a manual of neeti. This Sanskrit word, derived from a root which means to lead or to guide, carries the connotations of worldly wisdom, prudence and propriety, as well as appropriate policy and conduct or by, extension, politics and statesmanship.” [1, xii]

Author

“Naaraayana has specifically acknowledged this source. In the ninth verse of his prologue, he names his four books and states that they have been composed by drawing from the Pancatantra and another work. The version of the Pancatantra from which he drew his material is, however, unknown at present. In some instances the Hitopadesa text is nearer to the Pancatantra’s southern recension, in others to the Kashmiri, the Nepalese or even the old Syriac version.”[1, xii]

Having named the author ostensibly as Naaraayana Panditha, the Hithopadhesa states that the work was commissioned by his patron Dhavala Chandhra [1, x] Where and when this ruler reigned is not entirely clear. The consensus view at present appears to be eastern India. Indeed, the prasthaavana (prologue) itself gives us some indication of the Panchathanthra’s protagonists. Aachaarya Vishnusharma is stated to have attended upon the court of King Sudharsana, of Pataliputra. It is worth wondering whether the Panchathanthra’s avowed Amarasimha of “the southern city of Mahilaropya” is in anyway related to this historical figure.

“As with many ancient Sanskrit authors, little is known about Naaraayana beyond his name. From the text of the Hitopadesa it is obvious that he was a person of considerable erudition, perhaps a court poet or preceptor, and evidently a devotee of the great god Siva, whom he invokes in both the opening and concluding verses. He addresses Dhavala Candra by the titles ‘Srimat’ and ‘Maandalika’ which have been rendered in the present translation as ‘illustrious prince’, but could also signify a viceroy or a provincial satrap. The territorial and other details regarding the life and rule of this dignitary have still to be discovered. It has been conjectured that the Hitopadesa was composed in eastern india. Its manuscripts have been founded in Nagari, Newari and Bengali scripts.” [1, xi]

Despite its deceptive simplicity, the Hithopadhesa’s composer proves its sophisticated nature through its practical principles and lucid understanding of the world. Rather than pie-in-the-sky theoretic frameworks, it deals in hard-nosed realities. Rather than roil in faux historical chaanakyan fantasy, it focuses on the reality of policy being the domain of princes, rather than prideful on-paper paupers. Indeed, even the ministerial Manthri class, per Raajadharma, was historically drawn from royal or aristocratic extraction. Amaathyas of the advisorial set could be more general and based on individual merits and expertise. Wisdom, after all, can be found even among the simple.

“When allowance has been made for some real progress in civilization, as in the recognition of the place of women in society, every fable in the Hitopadesa can still be applied to human character; every maxim quoted from the wise” [2, v]

Composition

“This work, entitled Heetopades, affordeth elegance in Sanskreet idioms, in every part and variety of language, and inculcateth the doctrine of Prudence and Policy—from the translation of Charles Wilkins [1, x]

This was only the second work, after the Bhagavad Gita, that was translated from Sanskrit to English. The compositional form of the Hithopadhesa is primarily in mukthaka or subhaasitha style. [1, x]

“Naaraayana also adds a sense of liveliness to many verses by having them recited by animal characters. The birds and the beasts of his tales comment on human foibles and discuss lifes’ problems with solemn quotations from authoritative texts. This lends a tongue-in-cheek charm to some of the stories, such as that of the aged tiger (I.i) sanctimoniously citing the scriptures to lure a hesitant traveler close enough to be devoured.” [1, xvii] Sanctimony, it seems, was a perennial problem of India’s, not only in real life, but in literature as well…

“Relationship with the Pancatantra

“The structure of the Hitopadesa is remarkably similar to that more ancient collection of tales, the Pancatantra. Both works have an almost identical frame story, and the principal narrator has the same name. Their relationship has been described variously by modern scholars. Basham considered the Hitopadesa to be a ‘version’ of the Pancatantra, Keith a ‘descendant’, Winternitz a recast, while Dasgupta and De described it as ‘practically an independent work’. A detailed study made more recently by Ludwig Sternback demonstrated that the Pancatantra provides the chief source of material for the Hitopadesa. Nearly three quarters of the latter, including almost a third of its verses, were traced to the older work.” [1, xii]

Despite the consonance between the two oeuvres, Hithopadhesa is a standalone opus on its own merits. Whilst Panchathanthra appeals broadly to the audience, to emphasise everyday practical principles, Hithopadhesa is statecraft for the “sophomoric”, so to speak…

“Compared with the five books of the Pancatantra, the Hitopadesa has only four. In these the order of the older work’s first two books—excerpt as found in the Nepalese text—has been reversed; its third book has been divided into two; and parts of the fifth book have been incorporated into them. The fourth book of the Pancatantra is mostly omitted in the Hitopadesa, and at least ten of the latter’s thirty-eight interpolated stories are not found in any Pancatantra version at all. Of the over two hundred verses traced to various Pancatantra versions, a majority are found in the first two books of the Hitopadesa.” [1, xii-xiii]

In the present time, the danger of incompetent koopastha-mandukas commanding their kingly-commanders on what policy to implement, based on a cursory reading of Arthasaasthra, is pandemic (if one pardons the pun). Statecraft is not simply about regurgitating memorised policy or single-factor criterion or context-free dharma. It is about understanding all circles of the mandala, and graduating to them as one progresses. The Hithopadhesa starts at the very beginning, at the innermost circle—then expands outward. It is only when all factors and all dimensions are considered, that the proper policy can be proposed.

Is it any wonder that Bhaaratheeyas vapidly alternate between supporting B to counter A, getting offending, then childishly turning to C to achieve revenge against B? Or worse, fickly going back to A? There is no understanding of the nature of A, B, or C—so what business do you have in statecraft?

It is therefore almost axiomatic that self-proclaimed digital “dharmrakshaks” fall for kaakollukeeyam, time and time again. Best friend-worst enemy dichotomies are almost designed to make ullu ka pattas out of these ullukaputhras. That is why, one begins with first the Panchatantra, then moves on to Hitopadesa, then Rajadharma, then Arthasastra, before finally studying Kootaniti. Our vidhusakas like to put cart before horse & jump to PHD, after only LKG. First study the basics properly, then you may graduate to the next level.

“Text and Translation

Unlike the Panchantantra, which exists in a number of recensions with notable differences, there is only a one main version of the Hitopadesa, though it may not be the ur-text. It has been critically edited several times, including by Max Muller in 1865. The longest text, containing 749 stanzas, is the 1864 edition of J.Johnson, while the shortest, which contains 655 stanzas and incorporates for the first time the Nepal manuscript already mentioned, is that of P.Peterson, published in 1887. A scholarly comparison of all the main editions concludes that ‘the textual differences between the various editions of the Hitopadesa are of little importance’. “[1, xvii]

Indeed, so appealing was its concise and pithy form (in contrast to the ponderous pedantry of the present…) that it is found in a plethora of languages to this day.”The Hitopadesa’s appeal as a compendium of sage advice in an attractive story form extended its currency beyond the confines of the original language. At the beginning of this century [20th], the Indologist Johannes Hertel noted that its translations already existed in Bangla, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Newari, Oriya, Tamil, Telugu and Urdu. The United States Library of Congress lists additional contemporary translations of the hitopadesa into Burmese, Dutch, English, French, German, Greek, Khmer, Russian, Spanish and Thai.” [1, ix]

This work is divided into 4 Books. These very much rhyme with the 5 collections of its predecessor, the Panchathanthra. Following the introductory portion, it steadily hand-holds the student-reader through the gaining of friends, the dividing of others’ friends, the waging of war, and finally, the attainment of peace. Tragically, in the current choleric cast of caste-obsessed kautilyas-wannabe, more emphasis is placed on the division of one’s own ranks and on alliance with inveterate foes.

This rank stupidity is common knowledge not only among Indians, but even among non-Indians. That is the true importance of mandala-theory. It helps you understand in-group, out-group as spectrum, not just singular caste or jackal-pack criteria. There is no honour among thieves, but the rest of the world will always consider blood to be thicker than water—so maybe don’t make such a big deal about drinking from the same fountain…

Ancient and antiquated parochialism aside, dating this composition remains nebulous at best. What has been determined with certainty is that it obviously post-dates the Panchathanthra and Neethisaara. As is often the case with a nation that was subjected to pillage and colonialism, the best extant manuscripts are often found outside of it.

“The Hitopadesa contains quotations from the political treatise Neetisaara of Kaamandaki, and the play Veneesamhaara of Bhattanaaraayana, which date back to the eighth century AD. The earliest Hitopadesa manuscript, found in Nepal, bears a date corresponding to 1373 AD. Between these two outer limits present scholarly opinion places its composition in the period 800 to 950 AD, or just over a thousand years ago.” [1, x]

Hitopadesa Books

- Prasthaavikaa/ Prologue

- Mithra-laabha

- Suhr-bheda

- Vigraha

- Samdhi

In summary, Naaraayana Panditha’s work is worthy of original appreciation. It brings to bear new insights, and clarifies bitter political realities that are even more relevant in this age of over-informed naivety and outright stupidity.

“The Hitopadesa is no pale imitation or mere aggregation of its source materials. What gives it a refreshing identity of its own is the skilful way in which Naaraayana selected and arranged his extracts from a wide range of other works, supplementing them occasionally with his own compositions and modifications to produce something distinctive. In the final stanza of the second book, he refers to his book as a garden or grove of pleasing stories. His art was essentially that of the compiler and the anthologist, assembling and presenting diverse tales and maxims in a manner which gave additional cohesion and impact to the whole. His grouping of verses, in particular, is harmonious for the most part, and designed to emphasize the moral of each tale.” [1, xvi]

Selections

1. “May success tend good people’s labour, By grace of him, on whose brow gleams, The moon’s delightful crescent favour, Bright as foam on Gangaa’s streams. Study of these counsels benefit, Gives to speech felicity, Skill in words, diverse and specific, And knowledge of right policy”(P, sl.1] [1, 1]

§

2. “An influx of money, constant health…a beloved wife, and one sweet-speaking (of gentle manners), an obedient son, and learning productive of wealth—these six O king, are the pleasures of the mortal world.” [2, 1]

§

3. “Learning if not kept up by constant study is poison; taking food after indigestion is poison; to a poor man a public assembly is poison; and to an old man a youthful wife is poison.” [2, 1]

§

4. “A man of merits, born of whatever parents, is honoured; (for) what is the use of a bow that is without string though made of a faultless bamboo staff (or a, what can a man of pure Kshatriya extraction do if wanting in martial vigour?” [2, 3]

§

5. “Men, endowed with beauty and youth and born of a very noble race but deficient in learning, do not shine as (do not ) the scentless Kimshuka flowers”. [2, 4]

§

6. “Food, sleep, fear and the enjoyment of carnal pleasures—these men share in common with beasts; surely the sense (or performance) of duty is their special attribute (distinguishing mark): devoid of this they are degraded to the level of…beasts”. [2, 3]

§

7. “Sacrificing, studying one’s prescribed portion (of the Vedas), charity, penance, truthfulness, patience, forgiveness and freedom from avarice—this is the eightfold way of doing religious duties as laid down in the Smritis.” [2, 7]

§

Click here to Buy this Book!!!

References:

- Haksar, A.N.D. The Hitopadesa.London: Penguin. 2006

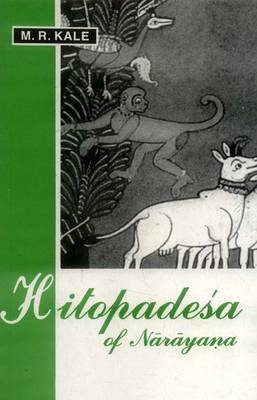

- Kale, M.R. The Hitopadesa of Narayana. Delhi: MLBD. 2015

Bhartrhari said: One should not wait until the house is burning to dig a well (sandipte bhavane tu kupakhananam pratyudyamah kidrsah)