Readers may recall our first article on Artisanry. Continuing our Series is the next installment which will evaluate Professions and Labour Organisation in more comprehensive detail.

Introduction

Understanding Aavesana means more than just studying the history. It means understanding implementation and even the political economy behind it. Many things today are over-analysed and many other things are too poorly understood.

In studying Indic Civilization it is important not to be too glossy-eyed, explaining away every flaw or mistake, but it also does not mean self-flagellation or willful misunderstanding. This sequel will evaluate Aavesana in greater depth and understand how it was meant to be implemented, and how, unfortunately, it (like any system) devolved into corruption over time. Doing so will ensure a clear-eyed study of the past so that an honest and pragmatic Revival can take place in the future.

Elites in every society make mistakes or fall from ancient heights. One must neither demonise nor deify our fellow man (Avatars notwithstanding, of course…). Rather, one must consider the needs of society as a whole, then ensure that high and low, elite and common, can live with dignity, decency, and self-respect.

Terminology

- Aavesana—Artisanry/Manufactury

- Kaaruchaaranakarma—Handicrafts/Artisanry

- Aavesanin—Artisans

- Kaarukarma—Craftsmanship/Handicrafts

- Chaarukarma—Performanceship/Graceful arts

- Karmantha—Manufactury

- Kaarmanthaka—Manufacturing Councillor

- Vasthra-karmanthikaa—Textile Manufactury Officer

- Udhami—Professional Builders Association

- Attaalikaa—Building

- Sthaana—Place

- Sthana—Udder

- Sthana/Svasaara—Stall

- Gostha—Cowshed

- Parnashaala—Hut

- Paanthashaala—Guest House

- Punyashaala—Hospice

- Graamya—Colloquial

- Gaarha—Household

- Gaarhapathya—Household Duties

- Khandakhaadhya—Confectionary

- Gandhayukthi—Perfumery

- Thakshana—Carpentry/Woodworker

- Tvashtri—Setting gems in gold)

- Samyoohya—Soldering

- Vaasitakam—Gilding

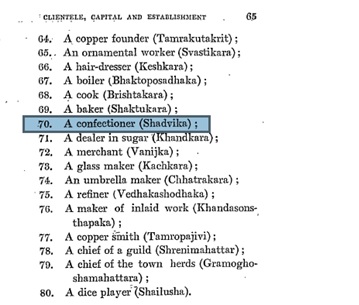

- Ashtadhasa sreni—18 guilds of Raajagrha (Goldsmith, Perfumer, Gemcutter, Oilpresser, Miller, Grocer, Rootist, Confectioner, etc).

- Sevanivrtthah—Retired

- Kinaasa—Peasant

- Angaaraka—Tailor

- Aapupika—Baker

- Prapavika—Bartender

- Prishtakaru—Beadmaker

- Dhamayaka—[Glass] blower

- Tapaniyakaru—Enameller

- Kaanchanakaru—Gemsetters

- Tvashtrakaru—Gilders/platers

- Dhanthakaara—Ivoryworker

- Aalepaka—Plaster Masons

- Medhaka—Basketmaker

-

Shaundaka/Shaundikaa—Distiller/Brewer

- Vaaraka/Vaarikaa—Royal Bellhops

- Paurogava—Chief Cook

- Chaamara-graahi—Cowrieholder

- Thuryakara—Trumpeter

- Sareeraparichaaraka/Angarakshaka—Bodyguard

- Kataka-kadhambaka—Food soldier/Forager

- Aaroha—Mahout

- Lesika—Elephant Feeder

- Karpathee—Attendant on elephant

- Nisaadhin—Elephant walker

- Thayaakarmikaa—Drinking water carriers

- Plavaka—Acrobat

- Maayakaara—Juggler

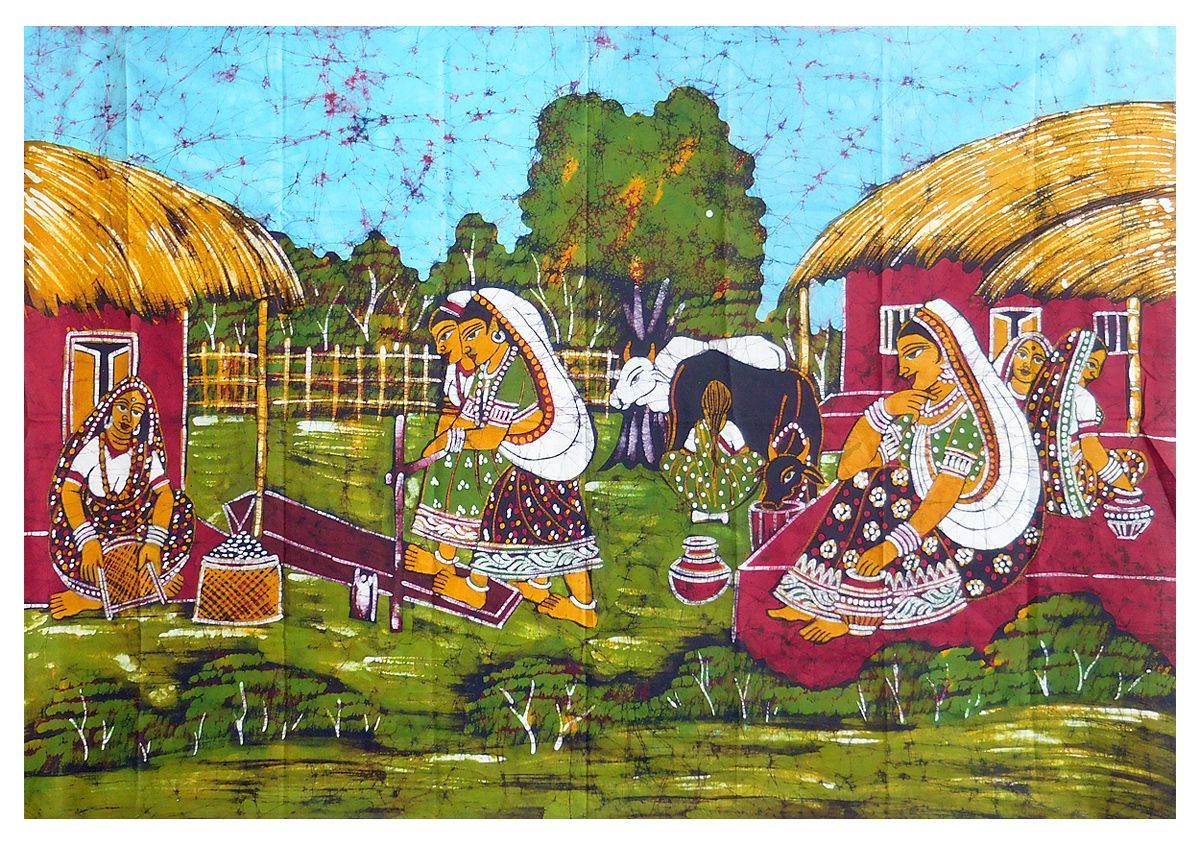

- Godhuh/Gopikaa—Milcher of cows

- Dhohaka—Milkman

- Thila-ghaataka—Oil presser

- Samvaahaka—Shampooer

- Kalpaka/Napitha—Barber

- Nejaka—Washerman

- Bhaaraka/Bhaarikaa—Porter

- Maarjaka—Sweeper

- Dhaaraka—Weigher

- Maapaka—Measurer

- Dhaayaka—Distributor

- Dhaapaka—Load Carrier

- Vaaguraka/Vaagurikaa— Trap-keepers/Hunter/Huntress

- Lubhaka/Vyaadha—Hunter

- Shaakunika—Falconer

- Sarpagraha/Vyaalagraha—Snake-charmer

- Pundaraka—Buffalo herdsman

- Dheevara—Fisherman

- Saadhayithayvya—To be accomplished

- Karthavyavinmukha—Averse to duty

- Kreedapatu—Skilled in Sport

- Kalaanipunaa—Skilled in Art

- Paakakushalaa—Skilled Cook

- Vardhaki—Skilled Carpenter

- Dhyoothaveenah—Dice Expert

- Vaidharana—Compensation

- Aardhika/Ardhaseethika—Sharecropper

- Bhrthi—Wage

- Bhrthaka—Wage-earner

- Praishya/Bhrthya—Worker/Servant

- Sevaka—Servant

- Aahithaka/Udhaaradhaasya—Mortgaged labour (labour-in-lieu of tax)

- Udhaaradhaasa/Ahithaka—Mortgaged Labourer (Debt Peon)

- Vishti—Corvee/ Conscript Labour (Emergency.Temporary govt. need)

- Vishtibandhaka—Corvee labourer

- Dhaasya—Indentured labour/Impressment/Bonded Labour

- Dhaasa—Indentured worker/Bondsman

- Dhvajaahrth—War Captive

- Aryapraana—Arya captive, now dasa

- Adhaasa syuh—Liberated

- Niravasitha—Excommunicated/Banished

- Mlecchabandha—Chattel Slave (foreign adharmic concept)

Professions

“kala meant an activity producing refined and sensitive effects. Adornment was an accomplishment, kala, cultivated with tests which literally meant art. Art and beauty are often synonymous with divinity. That Beauty was an element that elevated man, leading up to bliss, is persistently stressed through every conceivable medium.” [1, 25]

As demonstrated previously, there were a plethora of professions for the peasantry of the past. In our era of samatha (equality), these notions of aristocracy and peasantry might seem dated, but it is crucial to demonstrate that other than 1 depressed class, the masses in general could live contently and be treated well. An honest living and a living wage is what the common man needs in order to support a family and live with a measure of dignity. The rest is just frivolity as a nation of millionaires has yet to be invented. Disestablishing generational untouchability is imperative, but it need not mean wholesale homogenisation.

There has been much discussion over the role of the fourth varna. Nevertheless, there is a clear continuum in his rights and privileges in Arya society, of which he was considered a member. “He was expected to run his inde-pendent house, which he supported by agricultural and artisanal occupation. Gautama informs us that the sudra could live by practising mechanical arts. It seems that sections of the sudra community worked as weavers, wood-workers, smiths, leather-dressers, potters, painters, etc.” [3, 98]

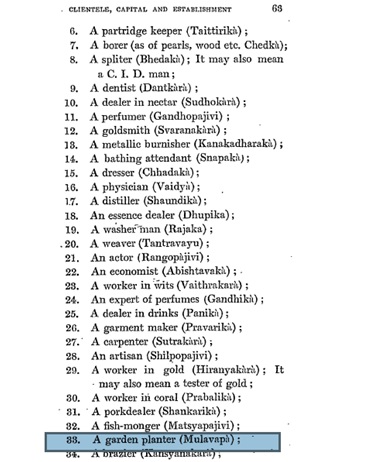

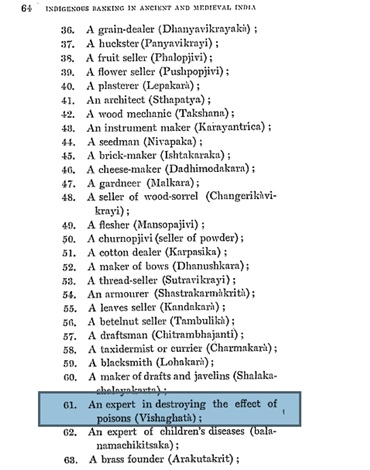

The vast array of occupations available for members of the fourth class ensured joblessness was relatively rare. The business cycle, recessions, and depressions were few and far between in that era, with only drought-driven famine, malgovernance, and war being the primary sources of unemployment and deprivation. Here are some additional occupations of ancient times that served to stave off chronic unemployment.

- Gandhopajeevi/Gandhikaa—Perfumist

- Snaapakaa—Bathing attendant

- Shankarikaa—Pork seller

- Malkaara—Gardener

- Dhanushkaara—Bowmaker

- Sutravikraayi—Threadseller

- Shashtrakarmakrth—Armourer

- Thaamboolaka—Betelnut seller

- Vishagath—Antiveninist

- Arakutakrth—Brass founderer

- Dhanyavikraayi—Grain-dealer

- Lepakaara—Plasterer

- Thakshaka—Carpenter

- Seedman—Nivapaka

- Isthakaaraka—Mason

- Dhadhimodhakaara—Cheesemaker

- Sthapathi—Architect

- Shaktukaara-—Baker

- Shadvika-—Confectioner

- Kachakaara-—Glassmaker

Labour Organisation

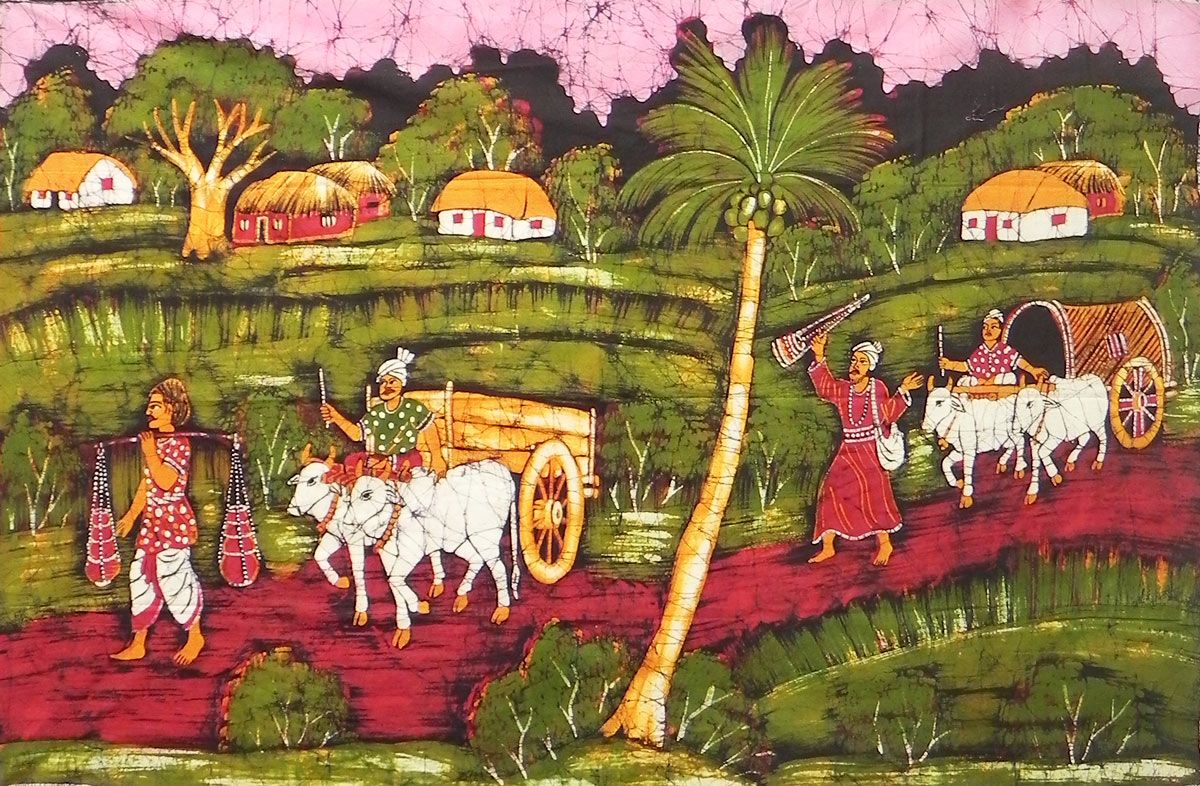

Srama Vyvastha (Labour System/Organisation) is a topic of much interest in the present era. Indeed, much ink has been spilled over the size and role of the ancient srenis and nigamas. It is well-known that these occupational associations were the basis for many of the modern ‘jaathis’ today, rather than the other way around. Guild associations led to inter-marriage, leading to communities dedicated to these occupations. This inter-dependence made possible a symbiotic rather than parasitic relationship between labour and finance.

“To some extent, a proper planning, with all administra-tive sophistication i.e., localization, specialization and ef-ficiency of labour, traditional groups were formed in the manner of associations or craftsmen for mutual benefits of their members.” [5, 172]

What’s more, entire villages and even towns were dedicated to trade and industry. “Gautama lays down that members of the various castes, and guilds of cultivators, traders, herdsmen, moneylenders and arti-sans could administer their affairs according to their respective customs, provided they did not override the dharma law. In other words those sections of sudras who were organised into guilds of artisans or castes could follow their own rules in the administra-tion of their internal affairs.” [3, 119]

The dharmic nagari was very different from the modern metropolis. Orderly planning courtesy a sthapathi (architect) would ensure that grimey and waste-heavy jobs were conducted away from city centers and water sources—unlike the present where man literally defecates where he drinks. As a result of this orderliness, one could have clear sense of which part of the city to go in order to access basic goods and necessities of life. While this was writ-large for the city and towns, it should be noted that even well-planned villages would have many of these amenities, storefronts, and designated access points.

As such, “guilds became localized in particular areas, and by now they gave impetus to specialization and efficiency of labour. We learn that within the town there was a localization of trade i.e. industrial villages or streets peopled by men following the same craft or calling, for example—the dyers’ street, the weavers’ place (thana) and so forth“. [5, 91]

Many of these agglomerations were entrepreneurial in nature, while others were clearly dedicated to a royal purpose or patron of status.

Many of these agglomerations were entrepreneurial in nature, while others were clearly dedicated to a royal purpose or patron of status.

“It seems that some artisans were attached to big house-holds; this can be said of the royal barber and royal potter and also a few craftsmen attached to big merchants. Other artis-sans such as smiths and carpenters lived in their own artisan villages, which were situated in the vicinity of towns. Obviously artisans living in suburban villages found their own raw mater-rial and produced their own commodities which they took to the town markets for the use of both the urban and rural folk.” [3, 101]

This organisation is apparent irrespective of whether it was a Bauddha or Vedic system in place. “The Guttila Jataka (No. 156) and Alinchetta Jat. mentioned about a guild of weavers who lived near Benares” [5, 91] .

The average village, therefore, might have many or most of the following buildings and enterprises:

§ Granary, Choultry, Grocery, Bakery, Dairy, Rotisserie, Fishery, Hatchery, Aviary, Apiary, Brewery, Winery, Distillery, Nursery

§ Laundry, Haberdashery, Chandlery, Perfumery, Bowery

§ Manufactury, Depository, Repository, Tannery, Cannery, Caskery, Smithy, Colliery

§ Chancellory, Constabulary, Armoury, Academy, Conservatory

§ Infirmary, Apothecary, Dispensary, Mortuary

§ Castellany, Cobbler, Pier, Abattoir, Tavern, Vintner

Cleanliness, of course, was imperative irrespective of the caste composition of a municipality.

“Manu introduces a new provision, according to which an area of about 400 cubits in width round the villages, and thrice as much around the towns, are to be set apart as pasture ground.” [3, 204]

Many industries, guilds, and even corporations (in the traditional, non-exploitative sense) evolved out of these municipal agglomerations. Rather than the vast, vertically and horizontally integrated zaibatsus, chaebols, and aktiengesellschafts of today, these srenis and nigamas were properly regulated and restricted by the Raaja, Pramukha, or Mantri.

“In actual practice, the state seems to have interfered with the affairs of the guilds when their actions prejudiced the general welfare or when they disagreed among themselves. ” [5, 91]

They reached a reasonable size, in a reasonable region, along a reasonable trade route, and stayed that way. The Samudhayas or Kulas (clan groups) that laboured for or even led these organisations, took them to a natural limit. Rather than faceless automatons, workers were treated as members of the wider family and labour treated with deserving dignity. It was by no means an utopia, but it wasn’t an Oliver Twist/Upton Sinclair industrial nightmare either.

“Wages of artisans were determined according to the quantity of work and quality produced. Fair deal to the worker had also been emphasized to curb the tendency to make illegal profits.” [5, 173]

The economic system was neither capitalist corporatism nor communism. What could best be described as Dharmanomics was not only the default Artha Vyavastha (Political Economy), but was an highly profitable and industriously efficient one at that. At a time of comparative advantage driven specialisation, it should be noted that diversified India was the veritable workshop of the world, with wares running across the gamut.

“Pliny the Roman historian is most concerned by the currency drain on the Roman Empire, not just Rome, because of imports from India…’It is well worth for us to notice that India takes away from the Roman empire annually a sum of 500 millions of sesterces…for her wares supplied, which are then sold at 100 times their original cost”. [1, 67]

Corporate welfare had a whole other meaning altogether with guilds providing cradle-to-grave coverage for workers and their immediate family. “According to a Nasik Inscription when money was deposited with a weavers’ guild, the rate of interest paid by them amounted from 1-3/4 percent per month. “ [3, 202]

As mentioned previously, perhaps the most famous among such humble industrialists was Saddaalaputta. “Five hundred potters’ shops under Saddalaputta and a large number of potters working under him clearly meant for supplying pots to both rural and urbal people.” [3, 101]

Many such individuals were well-compensated and some grew to be wealthy enough to engage in small-scale philanthropy. “We have a large number of recorded gifts of caves, pillars, tablets, cisterns etc to the Buddhist monks by smiths, perfumers, weavers, goldsmiths and even leather workers in Gaya, Sanchi, Bharhut and the Nasik area. Besides these, dyers, workers in metal and ivory, jewelers, sculptors and fishermen figure as donors in inscriptions.” [3, 199]

Involuntary Servitude

Slavery is a delicate topic in any society, and indeed, is condemnable. However, those most frequently demanding context are quick to ignore context or even nuance when the shoe is on the other foot. Specifically, the question of whether or not Slavery existed in Ancient India is a dogged one and remains occluded even to the clearest of eyes. Irrespective, it is clear that foreign invaders certainly did practice and bring it to India, and victimised the local population of all classes and castes. But when asked about this, the caste system is brought up as though they were the same thing.

Then the question of the term ‘dasa’ (pronounced dhaasa) is raised, ignoring that it was indentured servitude. If European (including Portuguese, Dutch, & French) especially British purchasing, deployment, and enforcement of slavery is raised, then Wilberforce is brought up—conveniently ignoring that Indian indentured servitude continued. In fact, one of the causes of the War of 1812 between Britain and the United States was English impressment of Anglo-Americans into the British Navy. And the less said about modern and post-modern debt slavery and debt peonage, the better. In short, ‘Do as I say, not as I do—and don’t bring up the past except when it suits me.‘

As such, proper estimation of Hindu Civilization’s virtues as well as its vices is required if any evaluation of the past and involuntary servitude is to be conducted. To do so requires a rapid perusal of the relevant terminology posted above.

Srama in Classical India came in many forms. The role of Asprsya (so called ‘untouchables’ or dalits) will be discussed in depth in the a future article. For now, the specific role of srama (labour) and sramikaa (labourer) will be discussed.

- Praishya/Bhrthya—Worker/Servant

- Sevaka—Servant

- Aahithaka/Udhaaradhaasya—Mortgaged labour (labour-in-lieu of tax)

- Udhaaradhaasa/Ahithaka—Mortgaged Labourer (Debt Peon)

- Vishti—Corvee/ Conscript Labour (Emergency.Temporary govt. need)

- Vishtibandhaka—Corvee labourer

- Dhaasya—Indentured labour/Impressment/Bonded Labour

- Dhaasa—Indentured worker/Bondsman

- Dhvajaahrth—War Captive

- Aryapraana—Arya captive, now dasa

- Adhaasa syuh—Liberated

- Niravasitha—Excommunicated/Banished

- Mlecchabandha—Chattel Slave (foreign adharmic concept)

Labour in India was multifarious and variegated. “This consisted of two ‘categories’, the ‘karmakaaras’ and ‘bhrtikas’, ie. who were regarded as free labourers working for a regular wage” [5, 105] in cash and in-kind. ” It should be noted that the Arthasaastra asserts “wages in cash were convertible into kinds at the rate of ’60 panas per adhaka‘”. [5, 105]

“A hired workman was named after (1) the period for which he was engaged e.g. maasika and (2) the amount of wages fixed to be paid e.g. panchaka. A month was the unit of time for calculating wages.” Patanjali plays a key role in illuminating fair wages and “he mentions a labourer working for one ‘padika’ coin (one fourth of a karsha-pana) a day, i.e. seven a half-karshapanas per month)“. [5, 104] “Manu further states that the wages of those employed in the service of the king—maids and servants—should be fixed according to the consideration of time and place. These workers, high (utkrsta) and low (apakrsta), should get the daily wages varying from one to six panas. Besides, they should get provisions such as food, clothes, etc. differing according to their status.” [3, 205] Elsewhere, it is stated that “a hired herdsman may milk with the consent of the owner the best count out of ten“. [3, 204]

There was also fair recompense to the employer in the event of fraudulent work. “According to Manu, if any body had refused to give the article for which he had taken the price and wages, they were charged with 4 suvarnas or 6 nishkas or 100 silver coins”. [5, 106]

Free Servant

A servant is a free person with unrestricted national movement who provides labour as service for a wage. This wage is generally paid in cash, but often in-kind. “A bhrtaka lived on wages, i.e. bhrti, which is mentioend by Panini either in the sense of service for hire or simply as wages. It seems that the brthaka was hired for a particular period.” [3, 110] This was the mainstay of labour in Ancient Hindu Society. Most Sudras worked as free artisans on contract or retainer or were employed as servants to the other 3 varnas. Thus, without wading too much into over-discussed varnashrama dharma, this was the origin of the Sudra caste (a part of Vedic, i.e. Arya, society), but not given access to dvija privileges (primarily Vedic education).

“These artisans were not attached to their clients the way as the dasas and the karmakaras were attached to their masters. Thus Patanjali informs us that the weaver was an independent worker. While the dasas and the karmakaras worked in the hope of getting clothes and food, the artisans worked in the hope of getting wages.” [3, 201]

In later ages, starting with the Sudra Nanda Emperors, Chandragupta Maurya (himself a Nanda per the Puranas), and many dynasties such as the Pala, Reddi, and Madurai Nayak dynasty, they would become businessmen, feudal barons, and even Kings. So quite apparently, there were changes in the Kali Yuga “caste system” so to speak, that were expansive. However, there were also changes that were constrictive. The first is the devolving of the term dhaasa.

Mortgaged Labour

The term dhaasa refers to indentured labour. The most common form of this was udhaaradhaasya, which refers to a free person who mortgages his or her labour to pay off tax or debt over a period of time. Raaja Harischandra was a celebrated Emperor of the Ikshvaku dynasty who gave up his kingdom to pay off his debt to Maharishi Vishvamitra. As even such munificent proceeds did not meet the required amount, he mortgaged his son and wife as dhaasas. This has been erroneously and egregiously touted as evidence of slavery—but it is quite the opposite. No man (certainly not a King) can be expected to sell his wife into sex slavery. She was in fact taken away to work as a servant (much like that other unfortunate Empress, Draupadi). That is the power of fortune and fate which can bring down even the privileged. “In all the cases Shama-sastry recognises that the aahitaka [udhaaradhaasa] is different from a daasa and describes him as a pledged labourer or a hireling.” [3, 179]

Thus, mortgaging of labour was a means of paying off a debt or tax. However, as society becomes immoral, people cannot be trusted with such power and in the ages that came after Raaja Harischandra, men began to exploit women dhaasas (i.e. dhaasis), but were also punished for it. Not only the Mahabhaaratha, which featured Bheema slaying prince Keechaka for his attempt to exploit the disguised dhaasi Draupadi, but even the Kautilya Arthasaastra lays out punishment for men who exploit their dhaasis—resulting in immediate manumission (liberation) of the dhaasya and mandated child support due to related pregnancy. [3, 180]

Indentured Labour/Impressment

In contrast to udhaaradhaasas, there were also indentured, impressed, or prisoner dhaasas. These were men and women who had become attached to a job or enterprise or dynasty on account of a debt (financial or otherwise) or were captured in war. Much of the issue with the term dhaasa stems from the racialisation of it. It is seen as synonymous with dasyu and dravidian. This association is incorrect. Dasyus may have in fact become dasas; however, the term Dasyu did not refer to ‘dark-skinned dravidian’: “in Iran there was a tribe ‘Dahae’ who were known as dasas in India. The Dasyus were a sub-tribe of these ‘Dahae’ people.” [4, 55]

Nevertheless, while they were attached to a court or a prisoner, dhaasas could not be exploited. Legalised, but heavily regulated, prostitution existed in ancient India as did polygamy. While patronage of a prostitute was condemned and frowned upon, keeping of a free concubine or wife was significantly different, and exploitation of free workers or dhaasis therefore carried with it corresponding punishment.

Many minstrels, dancers, and singers, were dhaasis in the sense that they were attached to the court and expected to serve it for generations in return for remuneration and maintenance. While technically not in debt, they were legally considered permanent employees of the court or institution on account of the education they received there or the generational connection with a particular family. They could be released by their liege-lord or given to another court. In contrast to chattel slavery, this typically did not involve the inhuman splitting of families, separation of couples, or alienation of dhaasa men from dhaasa women. Since they married as they pleased, these chaarukarma dhaasis could not even be classified as serfs (common in medieval Europe), as they had greater rights. They were simply attached to the land or liege-lord, and would generally only travel as directed.

Men who were impressed or indentured were rarely exploited though no doubt exceptions were there and punished if discovered. “The king had to do everything for fairness of justice to all individuals of the state.” [5, 103]

Corvee/Conscript Labour

The next form of involuntary servitude is vishti. Corvee or conscript labour is not unknown in eastern Asia. Many great constructions, like the Great Wall were in fact constructed using corvee. Similarly, in times of trial and tribulation, citizens are conscripted the world over to deal with the emergency. Even in very liberal Western countries today, doctors and other medical responders can be “deputised” [euphemism for conscripted] by the government to respond to States of Emergency. Vishti in its most elementary form can be viewed in such a fashion. “The most common source for such labour involved stateless societies and in early states in the Corvee, a forced labour“. [5, 103]

Not only states of emergency, but criminals and prisoners of war can be put to work on behalf of the polity (also done today in self-touted liberal democracies). What matters with any system is how it devolves. Just as there are private prisons for profit today exploiting groups from particular racial backgrounds through a slanted justice system, vishti too over the ages devolved. In turkic polities like the Nizam of Hyderabad, vishti (known as vetti chaakiri there) this became shorthand for outright slavery (permitted according moslem law). To retro-actively fault dharma or the vedic religion for that is non-sensical. Certainly there were excesses in ancient India, but this type of goebbelsian approach to blaming others for one’s own sins must stop. To end exploitation, one must correctly understand what vishti was, is, and what it became. Ancient Hindus simply did not maintain vast marketplaces for slavery (the likes of which existed in Ancient Greece & Rome and have returned to a newly religious Libya for example).

“The old provision that artisans should work for a day in a month for the king…continued to work in practice, for an inscription of the sixth century A.D. in Western India states that forced labour (visti) should be imposed on smiths, chariot-makers (rathakaaras) barbers and potters by the elders (vaarikena).” [3. 262]

It is also known that Megasthenes, not the best or worst source on Ancient India, spoke of how there were no slaves. How does this reconcile will the term dhaasa (frequently mistranslated as slave)? As A.L. Basham stated “There was no caste of slaves: though the Artha-sastra declares that servitude is not in the nature of the Aryan (in which term the humble sudra is explicitly included)“. [6, 152] If there were slavery in Ancient India, it was of such mild form that Greeks did not notice it. In short, while involuntary servitude did exist in Ancient India, slavery (especially chattel slavery) was certainly banned by Dharmic states and seen as Adharma. The same cannot be said of Hindu Civilization’s Civilizational counterparts the world over.

Chattel Slavery

Chattel slavery was undoubtedly one of the most condemnable institutions produced by mankind. But while it was heavily practiced in Mesopotamia, Abrahamic Judaea, Eastern and Western Christendom, and reached its peak in the Arabic or Saracenic world, it was not permitted under Vedic or Dharmic India.

Indeed, later accounts from Indic sources condemn the usage of chattel slavery by Persian, Arab, and Turk Invaders (and most notably the mughal invaders) who practiced near genocidal slavery on the native Hindu population. The Portuguese and the Dutch later capitalised on this by merely “purchasing” Hindu slaves and shipping them off to South Africa and Indonesia—until Chhatrapathi Shivaji banned it. British servants (including the infamous Anglo-American Elihu Yale) continued this practice until the British Parliament in all its munificence banned it—and proceeded to transport Indian indentured servants to Africa and the Caribbean instead to “work off their debt”. This form of exploitation is nothing but a colonial form of human trafficking that continues to this day in self-proclaimed humane Western Countries (i.e. Germany). After all, if one cannot see it, it must not be happening. Today it is merely couched in cuddly corporate marketing and shell companies. The Dutch, French, and English East India Companies would no doubt be proud.

All this of course isn’t to gainsay or undercut the genuine suffering and justifiable grievance of our Dalit brothers and sisters today. Indeed, it would take a separate article (or indeed, Series of articles) to do justice to their experience—not just their trials and tribulations, but also their triumphs. Any society or civilization has its elite miscreants and criminals, as well as its men-of-conscience and even men-of-morality. No doubt, the exploitation of dalits did take place not just in medieval India or ancient India, but even continues in modern India. But it is also not so simple as savarna-avarna, birth or ews reservation or creamy layer, or religion A…or B and C, it takes place on an industrial scale driven by internal bigotry sure, but also external and international commercial interests as well. And however tragic it is, it simply was not nor is not the execrable institution of chattel slavery, where human beings are literally treated as tangible property with legal rights over the whole person and her body. Understanding context necessitates understanding not just the politically convenient, but all pertinent circumstances to finally minimise and even end exploitation of both high and low.

“Manu lays down the same moral code for the members of all the four varnas. They should practice non-injury, truth, non-stealing, purity, sublimation of passions, and freedom from spite, and should beget children on their wives only.” [3, 233]

This good conduct or Sheela could best be described as the Common or Saamaanya Dharma. It should also be noted that the ancient law-givers stated that “brahmanas who do not maintain good conduct (sila) should be regarded as sudras.” [3, 310]

Conclusion

The world today stands at a precipice. On the one hand, it is seemingly a technotronic utopia full of endless possibilities, and on the other, a slowly unveiling technoslaving dystopia, where citizens are branded for labour—cradle to grave. An humane society, an ethical society, doesn’t simply tout the line “greatest good for the greatest number” but seeks out the moral treatment of all members of society. It tackles the social ills of the past, while retaining & restoring its best features. Not to play platitudes, but in the name of jumping out of the frying pan, one should not fall into the fire. Or in short, don’t throw the baby out with the bath water. Indic or at a more essential level, Dharmic Civilization, did not and does not sanction chattel slavery or serfdom.

The same cannot be said for ancient, medieval, and colonial Europe, the Middle East in general until very recently (though it has been revived here as well), and in other forms, East Asia. Serfdom was merely a rebranded slavery and existed until the mid 1800s in European Russia. Exploitation of labour takes place in many forms across many time periods. That is why dharma exists—to prevent exploitation, or where it occurs, to punish the exploiter rather than blame the victim.

But dharma also asserts that innocent people should not be attacked for the sins of others or for the sins of their forebears. Aggressor and victim can be found in all classes, only power equations at different points in time change the balance of evil. It is for this reason that rather than raillery or wrath against all the wrong people, solutions must be developed so that gainful employment can be found, families can be fed in contentment, and bills paid without debt.

Aavesana is the cure for the short-term problem of unemployment and under-employment, and eventually, societal discord and over-competitiveness. Those who demand varnashrama dharma should first practice it properly in their own lives rather than using it to adharmically corner political power. Casteism can no longer be allowed to masquerade as “Nationalism”.

It is often argued, erroneously, that jaathi is synonymous with varnashrama dharma. It is not. Sri Krishna speaks of Chaturvarna, and yes, the system was historically birth-based (guna-karma being a qualifier and disqualifier). However, quality-control is a perennial fear for casteists who lack guna-karma and sheela. For this reason, they have taken recourse to jati. But jati was not discussed as part of the system by in the Bhagavad Geetha, even the mention of it by Arjuna was in ambiguous context, at a time when rakshasa and gandharva jati are said to have also walked alongside maanava jati. It is only in much-maligned & much-manipulated manusmrthi that we first see its exhortation as some sort of natural system co-terminous with varna.

“The jatis are described for the first time in Manusamhita. And this Jati or caste system has been imposed on the former four-rank system.” [4, 26] “Manu converted Varna into caste or Jati”. [4, 27] But after careful consideration of a number Manusmrithi editions, it becomes clear that multiple recensions have been manipulated. Jaathi has been grafted onto Varnashrama Dharma for the benefit of the same people who believe priests and rajgurus should be ministers (itself a violation of varnashrama dharma). Rather than blame venerable Vaivasvatha or Svayambhu, it is clear that a more recent or more medieval malcontent was at work.

“Manusmrti was [re] written by Sumati Bhargava after 185 B.C. that is after the revolution of Pusyamitra. As a Brahmin Pusyamitra should not have murdered his king but actually did.” [4, 25] Irrespective of the later allegations of Buddhists against Pusyamitra Sunga (who assassinated the last Maurya), and the crimes of his last Royal descendant against his own Brahmin minister, much-manipulated manuscripts of Manusmrthi should be viewed critically and evaluated. This can be done even whilst respecting venerable Vaivasvatha or Svayambhu and considering the possibility that select verses were later corrupted for the benefit of a few. Surely the Manusmrthi is much older that 185 BCE—but could it have first been corrupted then?

“The Vayu Purana and the Brahmanda Purana state that in the Kali age the sudras act as brahmanas and vice versa [i.e. brahmanas act as sudras]” [3, 234]

The innocent are not to blame for the sins of the guilty, societal discord ends with the lowest common denominator, and varnashrama dharma is not jaathivaadha. Kula, Gotra, Varna, Desa, Samudhaya all were identities attached at birth, and rarely (if at all), modified later—but whither jaathi?? After all, jaathi means race; how can it be illogically applied to caste unless some subcastes are in fact of another race as claimed?—only those from raakshasa or pisaacha jaathi would think so… The sooner people understand this the better, and the sooner they stop demonising other castes (whether “high” or “low”) the better.

“Baudhayana states that the brahmanas who tend cattle, live by trade, work as artisans, actors, servants or usurers should be treated like sudras.” [3, 137]

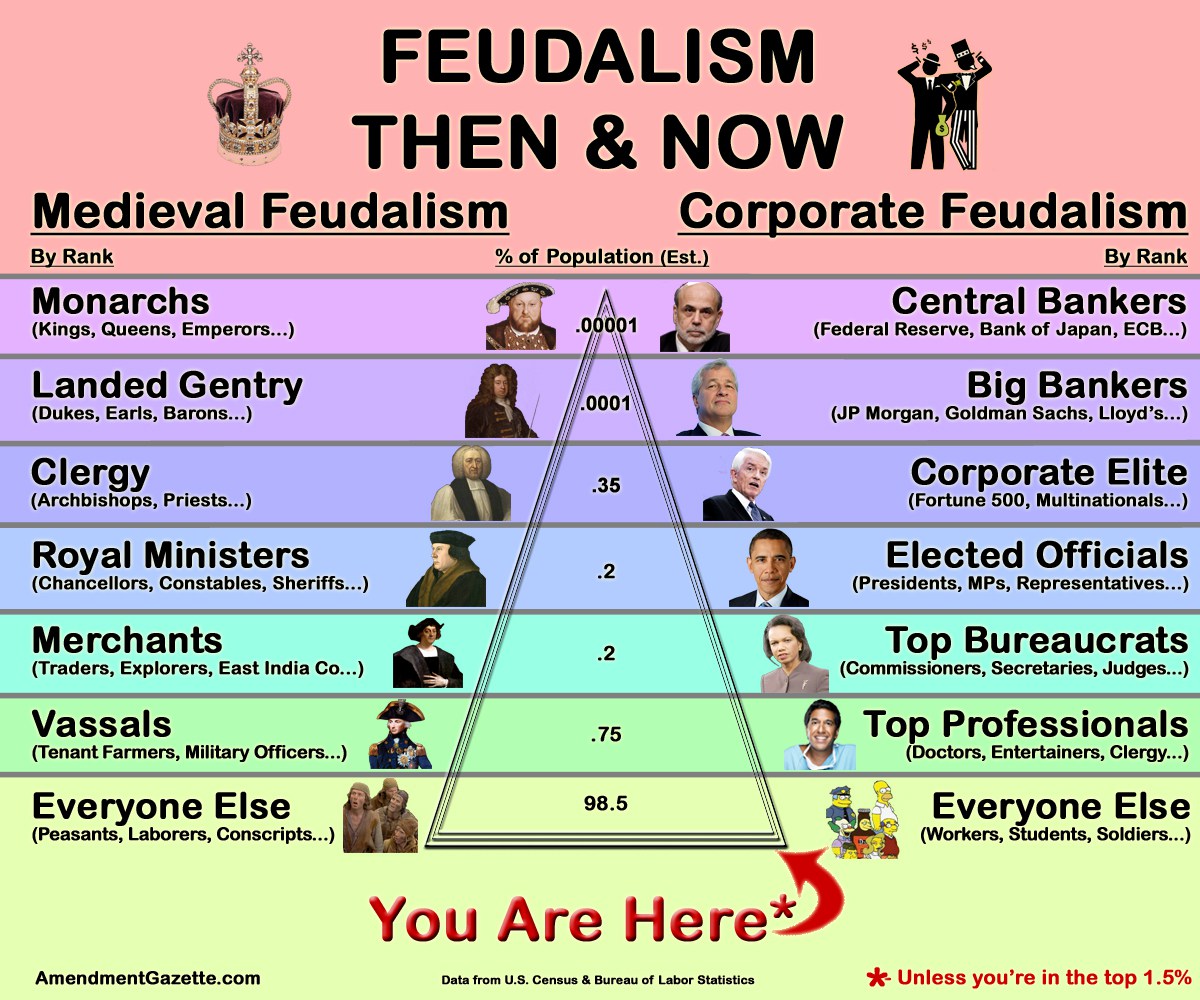

Those who wish to end the caste system must also study how birth continues to function in the corporatised class system (which is topped by European royals even today—apparently mediawallahs are fine with colonial colour systems…).

Aavesana celebrates hard work and free and independent labour. It emphasises dedication to a craft no matter what your caste, so that you can live by what you earn, be protected from exploitation, and have esteem in your end-product. Instead of just a corporate worker drone or communist revolutionary, the dignity of free labour under the auspices of the general dharma (be it Buddhist, Jain, Sikh, or Hindu) should be encouraged.

References:

- Chattopadhyay, Kamaladevi. India’s Craft Tradition. Publications Division, GOI. 2000

- Ayangarya, Valmiki Sreenivasa. Lokopakara (For the Benefit of People). Asian Agri-History Foundation. Secunderabad. 2006

- Sharma, Ram Sharan. Sudras in Ancient India. Delhi: MLBD. 2016

- Goswami, Subuddhi. Dalits in Ancient Indian Literature. VIIth Volume of the Journal of the Dept. of Sanskrit. Rabindra Bharati University. Calcutta. 1997

- Singh, Kiran. Textiles in Ancient India. Varanasi: Vishwavidyalaya Prakashan. 1994

- Basham, A.L. The Wonder that was India. New Delhi: Rupa.1999