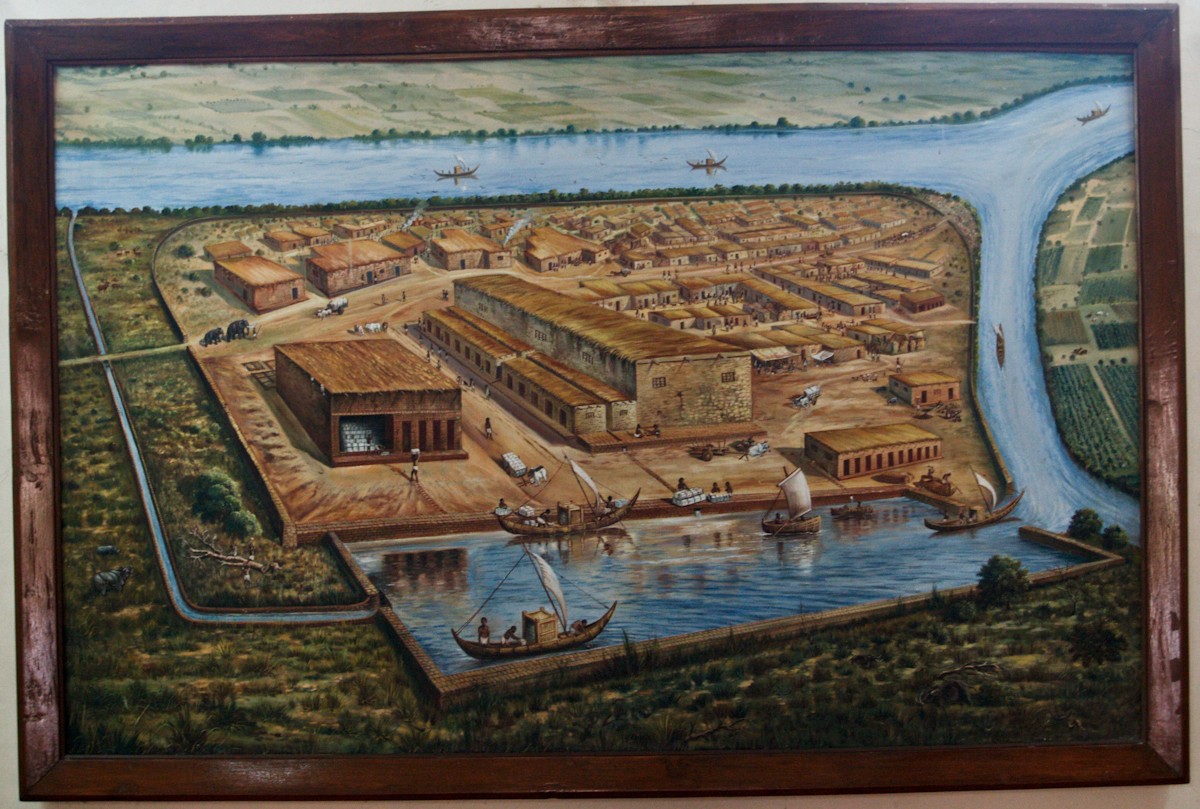

Long after the antediluvian city of Lothal, was a long tradition of trade and business. One of the more interesting and ostensibly profitable aspects of Indic Civilization is Commerce. Judging by the ‘shopkeeper mentality’ of medieval and modern Indians, more so than other countries, the business of India has long seemed to be business. While that is not actually the case, there is no denying the critical importance that Commerce and Political Economy in general has had in Greater India. But the Dharma of Commerce is neither capitalist nor socialist, but inherently its own system.

The Political Economy (Artha Vyavastha) of Bharatavarsha is one that that rejects both greed and penury. The Indian merchant (vanija) has become equal parts world famous and nationally infamous for his success and ability to turn a profit in the most adverse of circumstances. What is the secret to his sauce? To find out, one must study Classical Indic Commerce, which is more traditionally known as Vaanijya.

Introduction

Goddess Lakshmi has long had a powerful influence on the Dharmic psyche. Though poor poets have often calumnied her as fickle, in truth, she has been loyal to the worthy. Those who have been the sustainers of Dharma and the pillars of society are those She truly blesses over the long term. Rather than the mere shareholder, it is the stakeholder of society who is thought of as worthy. He who accumulates his wealthy honourably and endows his nation generously, is seen not only as a successful businessman (vyaapaarin) or rich man (dhanavaan), but also as an eminent citizen of society (paurika). And this is the reason why despite the modern antipathy towards “mercantiles”, vaisya dharma itself should be seen as something noble when conducted correctly. Dharmasya moolam Artham (the root of Dharma is Wealth). For Dharma to truly be strong, wealth (in the form of food and resources) is required for society to function. But it should also be remembered that Arthasya moolam Raajyam (the root of Wealth is Power) and Raajasya moolam Indriyavijayam (the root of Power is victory over the senses).

Nevertheless, many Gurus have in fact remarked that study—even spiritual study—is possible only on a full stomach. Thus, the role of Commerce in circulating goods and services serves both the highest and lowest aims in Society. Vaishya Dharma traditionally encompassed trade, agriculture, & pasturing, with cattle being central to all 3. Sri Krishna himself long lived among gopas and gopikas as a Vaisya, and exhorted the centrality of the cow to prosperity.

Dhenoh paripaalana kshemaya bhavathi

But if that is the origin of Classical Indic Commerce, what is its general nature, tradition, and history?

For the sake of simplicity, Indic Commerce can be divided into 3 phases: Ancient, Medieval, and Colonial. Modern has been omitted because modernity and post-modernity have effectively suborned the native systems. However, decline was apparent in the ancient period itself. Mercantile power began to assert itself to the point of occasionally dictating to political power—in express contravention of dharma. As such, the ideal-state will first be stated, after which period-based study and commentary will follow.

Terminology

- Vaanijya—Commerce

- Vanija/Vanik—Merchant

- Vyaapaara/Vyavasaaya—Trade/Business

- Vyaapaarin/Dhurina/Dhurandhara—Businessman/Trader

- Dhanavaan/Chanin—Rich man

- Arthacharya—Doing business/Wealth generation

- Udyama/Vyayama—Industry/Activity

- Udyoga—Job

- Srama—Labour

- Sreni—Guild

- Kreni/Aaparga/Vipani—Market

- Aapanam—Shop

- Aapanaka/Aapanika—Storekeeper

- Pattana—Port

- Vachana—Numbers

- Vilaasa/Sukhaana—Luxury

- Karamukta—Tax free

- Kara—Tax

- Vyaji—Transaction tax

- Krshaka—Farmer

- Krshi/Halabhrti—Agriculture/Farming

- Vittakosha—Bank

- Vitta—Banking

- Saamkhyaayaka—Accountant

- Karanam/Karanika—Accounts Officer

- Nibandhaka—Ledger-keeper

- Niranka Pratyaya—Blank Credit

- Ganitham—Sum

- Kosaajna—Finance

- Avakraya/Aayakara—Revenue

- Vyaya—Expense/Cost

- Laabha/Phala—Income/Profit

- Nastha—Loss

- Nasthanidhi—Bankrupt

- Arjanam/Praapthi—Acquisition

- Sampatthi/Artha—Asset

- Dheya—Liability

- Svathaa—Equity

- Nikshepa—Deposit

- Rna—Debt

- Vrddhi—Interest

- Vaardhusee—Usury

- Kuseedhaka/Kuseedhika—Money Lender

- Kaasu/Karsha—Coin

- Varaataka—Cowry shell

- Vikraayaka/Vikraayika—Salesman

- Kraya-vikraya—Purchase & Sale

- Prapana—Bargaining

- Prathipana—Counter bargaining

- Charita—Transaction

- Utthita—Principal & Profit

- Moolya—Value/Price

- Parikryana—Employment

- Prakrya—Royalties

- Prayoktr/Parikretaa—Employer

- Karmachaarin/Parikrta—Employee

- Praadhikarana—License/Authorisation

- Upaayanakrtha—Charter of Privilege

- Abhivrddhi—Growth/prosperity

- Vinyaya/Stithi—Office/Position

- Kaaryaalaya—Office/Place of Work

- Mudra—Seal

- Hasthaankana—Signature

- Vethana/Bhrthi—Salary/Wages

- Vethana-sreni—Pay scale

- Vethana-vrddha—Increment

- Vethana-adhikadhaana/Adhivethanam—Bonus

- Yantra shaala—Factory

- Yantrakaara—Factory worker

Classical Indic Commerce

Vaisya Dharma extended across a number of disciplines. As Sri Krishna stated in the Gita:

Krishi goraksha vaanijya Vysya karma swabhavajam Agriculture, cow protection and trade of goods is the karma of a Vysya [3, 664]

Svami Chandrasekharendra Sarasvati, better known as Mahaperiyava, echoed this when he stated the following:

“The Vaisya too serves society—to think that he takes home all the profit he makes is unfair…The third varna has three duties—the raising of crops, cow protection and trading—and it carries them out for the welfare of all people. The Vaisya ploughs the field and grows crops for the benefit of the entire community. Similarly, the milk yielded by his cows is meant for general consumption and for sacrifices. A Vaisya must also take care to see that the calves have their feed for milk. As a trader he procures commodities from other places to be sold locally.” [3, 664]

Agriculture, Cattle-rearing, and Commerce were seen as part of the same spectrum, precisely because there was an expectation that people not take advantage of each other. Indeed, most of India’s most famous business communities (Marwaris, Sindhis, Jains, Agarwals, Kammas, Chettiars) operate on the basis of trust. If the community is taken advantage of, then social boycott and ejection from the system is the penalty.

As history will show, the honest trader and cow protector would increasingly stand distinct from the notorious House of Jagat Seth. But this is a topic for a future article. Instead, the topic at hand is one that celebrates the historically honourable profession of trade. Indeed, many successful merchants in Ancient India, find respectable mention even today. One such is Anaathapindika.

“We also hear of merchants travelling from Kashmir and Gandhara to Videha, from Benares to Ujjayini, from Magadha to Sauvira and so forth. What vast wealth accrued from this system of inland trade is illustrated by reference to merchant princes like Anathapindika of Sravasti whose trading connections extended to Rajagriha on the one side and Kasi on the other.” [8, 268-9]

Anaathapindika was an highly successful merchant in Ancient Madhyadesa. He is said to have been one of the earliest endowers of the Buddhist Sangha. Thus, from mere cattle-herder or petty merchant, stood the potential for dharmic Vaisyas to become Eminent Citizens. One who does philanthropy (paropakaara) and engages in public service (jaana seva) is an eminent citizen (gaura paurika). Many were often appointed to positions of importance on the City Council or as bureaucrats and district accountants.

Interestingly enough, the term karanam (accountant/account officer) was originally used for inter-caste children of vaishya men and sudra women in the time of Manu himself. Ironically, the karanam system of Andhra Pradesh (patel-patwari in Telangana) became appropriated by Niyogi brahmins in later periods (demonstrating decline of varnashrama dharma). Regardless, it is clear in both the ancient era and medieval period, that Merchants and Commercial leaders had a prominent place. They were seen as a pillar of Dharma and not only profited from business but contributed back to society.

“In the past, the Cettiars [of the South] built dharmasalas [free boarding and lodging houses] for pilgrims from Kasi. Correspondingly, the Sethjis constructed dharmasalas for pilgrims going to Kasi and Badrinath.” [3, 671]

Elements of Vaanijya

If Classical Indic Merchants were as successful as modern ones, then what were the elements of their success? What were the institutions they utilised in order to not only enrich themselves but their communities and countries? One institution is one that is not so modern after all.

Kreni (Market)

While free-market fundamentalists believe only in the extremes of materialism (state & individual), Indic Civilization historically provided for a healthy free-exchange of Goods & Services, under the regulation of Dharma. The Market, Kreni, was very much alive in most cities and towns of Ancient India. It was also known as aaparga and vipani, but its value cannot be gainsaid. The Arthasaastra is illustrative here:

“The King shall promote trade and commerce by setting up trade routes by land and by water and market towns/ports. {2.1.19} Trade routes be kept free of harassment by courtiers, state of-ficials, thieves and frontier guards and from being damaged by herds of cattle. {2.1.38}”[4, 235]

“Frontier officers shall be responsible for the safety of the merchandise passing on the roads and shall make good what is lost. {2.21.25} Traders may stay inside villages after letting the village officers know of the value of their merchandise. If any of these is lost or driven away, the village headman shall recompense the trader, pro-vided that these had not been [deliberately] sent out at night {4.13.7,8}” [4, 235]

World-renowned Indian negotiating skills aside, haggling was not based on merely bilking of the buyer. Fair price was asserted to guide purchase, rather than arbitrary greed. “Prices shall be fixed taking into account the investment, the quantity to be delivered, duty, interest, rent and other expenses. {2,16.2, 3}”[4, 237]

Often craftsmen could become successful industrialists in their own right. One such name known to the Jain texts is Saddaalaputta. He was a potter who became very wealthy, eventually owning 500 potter workshops and a fleet of boats throughout the Ganga system. [6, 216]

“Arhat, too, was an indigenous word, meaning ‘agency for selling someone else’s goods by charging commission’ and also ‘the godown where such goods are stored’…The arhatiya gave a guarantee in a transaction between the buyer and the seller who might be at a great distance from each other, and he there-fore charged a higher commission than an ordinary broker (dalal) who simply brought the buyer and seller together.” [6, 126]

Sreni (Guild)

The centrepiece of ancient Indic commerce was the sreni (guild). “There are faint and uncertain references to some guild organization even in Vedic literature, but by the time of the composition of the Buddhist scriptures guilds certainly existed in every important Indian town, and embraced almost all trades and in-dustries” [6, 216]

However, this was not a mere medieval obsolescence. Rather than a gang of thieves salivating over profits, it was was a body of associated traders or artisans who retained a high-minded public spirit, and a sense of mutual responsibility.

“The guild united both the craftsmen’s co-operatives and the in-dividual workmen of a given trade into a single corporate body. It fixed rules of work and wages, and standards and prices for the com-modities in which its members dealt…a guild court could, like a caste council, expel a refractory member” [6, 216] “It acted as a guardian of their widows and orphans, and as their insurance against sickness.” [6, 216]. “The guild was headed by a chief, usually called the ‘Elder’ (jyesthaka, in Pali jettaka), who was assisted by a small council of senior members.” [6, 216-17]

Not only where they very active in safeguarding mutual interest, they demonstrated their civic-mindedness and charity to causes both religious and general. “All over India are to be found inscriptions recording the donations of guilds to religious causes of all kinds, the most famous being that of the Mandasor silk-weavers” [6, 217]

They also a had a strong financial angle. The wide distances of trade demanded some assurance about mutual protection of goods and interests. Instead of carrying heavy specie over long-distances, they needed to have a secure means of payment and store of value. “They sometimes acted as bankers and trustees. There are references in the legal literature to guilds accepting de-posits, and lending money at interest to merchants and others. They would often act as trustees of religious endowments.” [6, 217]

While this was an all-India phenomenon, South of the Vindhyas, saw a legendary rise of a ‘company of gentleman merchants’, so to speak.

“Such merchant corporations be-came very important in the medieval Deccan, and had branches in many cities. One such was the Viravalanjigar, freely translated as ‘the Company of Gentlemen Merchants”, which had members in every important city of the Peninsula and was controlled by a central council at Aihole” [6, 223]

In those days, the Indian Subcontinent was far more commercially accommodating. Areas of operations for these guilds extended far beyond the borders of modern India.“The company known as Manigrama functioned not only in Southern India, but also in Ceylon, where it hired its mercenaries to the Sinhalese kings.” [6, 223]

The Sri Lanka was a treasure trove of precious and semi-precious products. This island of heavenly delights showed the inter-connectivity of Classical Indic Civilization. “Sinhalese memory goes back to a time prior to the advent of Vijaya when trading vessels coming in sears of local products like ivory, wax, incense, pearls and gems were sometimes wrecked on the shores of Ceylon…By the beginning of the Mauryan period in India, however, we may be certain that important settlements had been established in different parts of Ceylon and a fairly high degree of culture attained.” [8, 256]

Above all, however, was that the nature of the sreni was to ensure a quality good for the consumer. The stamp of the sreni would stand for high standards, and their counsel to kings played a key role not in dictating commercial policy, but in providing a healthy input into it.

“Members travelling to strange cities would receive help from officers of the local branch, and, like the craft guilds, the mercantile companies no doubt helped members who fell on hard times, prevented adulteration, undercutting and other malpractices, and represented their members at the king’s court.” [6, 223]

Vittakosha (Bank)

One of the outcomes of the Sreni was banking on a large-scale. Indeed, it was trade that necessitated the bank, rather than the other way around. Nevertheless, money and coinage antedated the sreni, and mention of it is found throughout ancient literature and archaeological evidence for it available throughout India.

Kaasu/Karsha (Currency/Coinage)

“The Vedic nishka, satamana and suvarna may have been ingots of gold of different weights. Of these nishka was probably a gold coin even in the Vedic age as it was later in the time of Manusmriti.” [6, 278]

“The earliest Indian coinage consisted of flat pieces of silver or bronze, of irregular shape, but fairly accurate in weight.” [6, 220] These are known today as punch-mark coins, the earliest of which are said to date back to the 8th century BCE. While silver was the most common denomination, and gold coins (suvarna) also in circulation, copper and cowry shells were common currency for lesser, daily transactions among the masses. [6, 221]

“The coins current in India before her contact with the Greeks were of the variety usually described as punch-marked and cast. Their manufacturing technique widely differed from that of the Greek coins, and it has been almost unanimously accepted that it was invented by the early Indian moneyers, without the aid of any outside influence.” [8, 123]

The natural outgrowth of coinage and money is money-lending. However, the laws were not rigged in-favour of financial interests. It was dharma that guided the rate of interest and the terms of payment.

“Humane regulations on indebtedness are laid down in the Artha-sastra and some other legal tenets. Interest payments should cease when the total interest paid equals the principal. Loans advanced on securities used by the creditor for his own profit (e.g. beasts of bur-den) should be free of interest.” [6, 222]

In addition, it should be adumbrated that the illiterate (or foolish) consumer was protected from himself as “the earliest Dharma sutras lay down rates of interest, and re-gulations governing debts and mortgages. The just rate of interest is generally given as 1.25 percent a month, or 15 percent a year.” [6, 221]

It should also be noted that mere money-lenders or even srenis were not the only ones making loans. As seen “in the South the village communes occasionally made loans to peasants. There were many professional bankers and moneylenders, however, the sresthins (in Pali, setthi) [stood apart]. The sresthin was not merely a moneylender or banker, but usually a merchant as well…banking in India was a by-product of trading, and most sresthins had other sources of income besides moneylending.” [6, 222]

“’There is the loan by the bunneah or village money lender, who deals with his own money alone, and there is the loan by the mahajan or banker, who deals with other people’s money as well as his own’. The moneylender operated with his own capital. The banker in the larger centres of com-merce, on the other hand, was into credit-generating hundi operations and he thus dealt with other people’s capital, mobilizing it for commer-cial rather than agricultural operations. The moneylender financed the cultivator by advancing him money for the purchase of seed, plough-cattle and ornaments, and got the money back in grain by hypothecating the crop. The banker did not enter into this type of petty commo-dity production. He financed trading operations between market towns and seaports, either by financing commission agents (arhatiya) who guaranteed long-distance deliveries or by acting as commission agents themselves. In this type of operation, the general credit of the country, the state of trade, export conditions, and the question whether credit was good or bad, figured importantly—considerations that did not enter into the moneylender’s more restricted business…The moneylender’s rates were necessarily much higher than the rates at which the banker discounted traders’ hundis.” [6, 122]

In fact, this last term of interest covers one of the more pivotal financial instruments in Indian history.

Hundika

“The documentary evidence of the Lekhapaddhati show-ing the practice of mortgage (twelfth/thirteenth centuries) as a means of credit has been too well known to be repeated here. Similarly, varieties of hundikas (bills of exchange) mentioned in post-tenth-century sources also take cognizance of agricultural products, animals, etc.—fore example, dhanya-hundika, yava-godhuma-hundika, ghot-kanama-hundika.” [5, 18]

Hawala today may have come under the scanner for its black money and atankwadi connections, but contrary to mughal enthusiasts, its origins were not middle eastern. Hawala’s actual name is Hundika, and originates as an instrument of Indic credit.

“Actually, the word was a modification of hundika, a Sanskrit word derived from the verb hund, that is, to collect…This bill also served as an instrument for credit, and as its use proliferated in the prosperous years before 1929, it largely became the instrument through which bankers raised funds from pensioned people and widows who purchased it for the interest it offered. The hundi was thus a substitute for the deposit.” [5, 126]

Thus, long before great banking houses of Europe had gained dominance of the world, Indic bankers and moneylenders were operating their own sophisticated system of credit and monetary exchange. This had benefits not only for national and international commerce, but also implications for public finance and national sovereignty.

“The standing of the sarrafs engaged in the hundi business ranged from relatively small dealers to very large houses with agents or correspondents all over. In the seven-teenth century, one such major house was that of Virji Vohra with its headquarters in Surat. During the first half of the eighteenth century, by far the most important sarraf establishment in the empire was that of the Jagat Seth family operating from its headquarters in Murshi-dabad, Bengal. Among its other extensive activities, this house handl-ed the remittance of central revenues from Bengal to Delhi amounting to over 10 million rupees per annum.” [5, 47]

Detachment from Dharma aside, medieval hundika was an efficient means of affording credit, without the weight or risk of specie loss during travel and transport. The volume of trade naturally ballooned, it is only government that failed to impose its writ to properly harness such an effective system. Above all, it was a fall of culture that failed to consider the common interest. Ironically, ancient traders had a little bit more common sense, and collaborated with one another and even the native governments of the day.

Pattana (Ports & Caravans)

Trade was a mainstay of medieval and ancient India. It was not only voluminous but carefully nurtured as a means of prosperity for all. The great centres of trade in the Ancient era include Thaamralipthi, Champa, Paataliputra, Kaushambi, Vidisha, Ujjayini, Bharukaccha (Bharuch), and Patala in Sindh. This was the East-West route. Then there was the famous Uttarapatha (Northern route) which went from Paataliputra to Mathura and from there to Takshasheela, Purushapura (Peshawar), and Kabul. [6, 223] Finally, there was the Dakshinapatha (Southern route), which went from Ujjain to Pratishtana (Paithan), and then to Andhra before finally reaching Kanchi and Madurai. [6, 224]

Due to the existence of dacoits, inside and outside India, caravans often featured large numbers of merchants banding together for security, sometimes as many as 500. “The caravan leader (saarthavaaha) was an important figure in the commercial community, and the Gupta copper-plates of Northern Bengal (p.103) show that the chief caravan leader of a locality might occupy an important place on the district council.” [6, 225]

The vulnerability of caravans to raiders and loss of profit led to mutual protection and risk management, in the interest of smooth business operations.

“Co-operative ventures both in production and distribution were well known in Hindu India, but they were normally carried out by tem-porary associations of craftsmen and merchants, and these merchant companies were in no way comparable to the modern joint stock com-pany.’ [6, 223]

Organisation was remarkably coordinated, and caravans were well-guarded in order to safeguard wares. These cooperative ventures ensured a measure of confidence and guarded against catastrophic loss, individual or community.

“Overland caravans, though consisting of carts and pack animals owned and led by individual merchants, would be organized and controlled by officers of the company, and guarded by the company’s mercenaries. They would play a similar part in maritime trade, and probably owned warehouses and ‘factories’, where their members might store their wares in safety.” [6, 223]

The logistical operations of these cooperatives was often exceedingly impressive—given the technology of the time. “From Tamralipti ships not only sailed to Ceylon, but, from the beginning of the Christian era, to South-East Asia and Indonesia.” [6, 228] Other famous port cities include the afore-mentioned Patala and Bharukaccha, as well as Machilipatnam. Musiris in the Malabar was known to videshis, as well as Kaaveripattinam and Korkai in the Coromandal coast.

Archaeological remains for these international entrepots can be found to this day.“The Tamil kings did much to develop their harbours and encourage sea-trade. We read of lighthouses, and wharves, where ‘the beauty-ful great ships of the Yavanas’ discharged their merchandise to be examined by custom officials, stamped with the king’s seal, and stored in warehouses. Kavirippattinam, now a decaying fishing village silted up by river mud, had an artificial harbor, built, according to a late Sinhalese source, by soldiers captured by the great King Karikaalan in a raid on Ceylon.” [6, 228]

There were a number of islands not only to the east, but also to the west that had the stamp of Indic Commerce. The Arabian Sea island of “Socotra had a considerable Indian colony, and the name of the island may be of Indian origin [Sukhatara-dvipa, ‘the most pleasant Island’]”. [6, 228] There is mention of Indian merchants as far as Rome, Alexandria, and Ethiopia as well.

Commercial Law

Commercial law was very robust and treated extensively in both Dharmasaastra and Arthasaastra. However, as with all things legal, law & order waxes and wanes with national stability and the power of the state. Often times, merchants feel pressure from adversity and cut corners, and other times they themselves are treated unfairly. While commerce was no doubt encouraged, not all business-people are honest. Kautilya certainly remained suspicious in his views.

“’Merchants…are all thieves, in effect, if not in name; they shall be prevented from oppressing the people.’ {4.1.65} Their propensity to fix prices by forming cartels {4.2.19. 8.4.36}, make excessive profits {4.2.28-29} or deal in stolen property {4.6.3-6} was guarded against by making these offences punishable by heavy fines.” [4, 86]

He seemingly stipulated somewhat meagre margins that would likely make modern merchants morose. “Profit margins were fixed at 5% for local goods and 10% for imported ones; making undue profit attracted a hefty fine {4.2.28, 29}” [4, 91] To what extent this parsimony was enforced is not clear.

Contrary to the present time where shareholder interest is prioritised, in the Dharmic Raajya public interest was supreme, and hyper-inflation anticipated and headed off:

“When there is excess supply of a commodity, the Chief Controller of State Trading shall build up a buffer stock by paying a price higher than the market price. When the price reaches the support level, he shall change the price, according to the situation. {2.16.2, 3}” [4, 237]

Nevertheless, while many of his suspicions have become validated in the present era of buccaneer capitalism, a gentle but firm hand was nevertheless advocated.

“The duties of the Chief Controller of Private Trading are listed in VII.v. Control over prices and trade practices was made easier by prohibiting sale of agricultural products or minerals at their places of production; selling at places other than the designated markets was also punishable {2.22.9-14}. In addition to his supervisory duties, the Chief Controller could also grant the appropriate exemptions if a mer-chant’s goods were damaged due to unforeseen reasons {4.2.32}” [4, 87]

These generous arrangements were remarkably consistent whether in ancient Magadha, late antiquity Rajasthan, or medieval Tamil Nadu. Indian Kings were known to, time-and-again, guarantee goods of merchants (foreign and domestic) in case of theft.

Foreign trade, in particular, was prized, being an excellent source of specie. The Roman Pliny famously bemoaned the adverse balance-of-payments to India.

“The importance of foreign trade is indicated by the advice given to the conqueror that he should pause after declaring war, if he could divert to his own country the valuable goods going to the enemy by a trade route. {7.4.7} …The official in charge of exports, the Chief Controller of State Trading, was advised to undertake foreign trade only if there was a profit, except when there were political or strategic advantages in trading with a particular country. {2.16.19}” [4, 87]

Despite his exhaustive discussion and plethora of minutiae, Kautilya himself was drawing on an earlier tradition. For example, Manava Dharma Saastra “prohibited some types of interests namely kaalika, kaayika, kaarita and cakravrddhi“, and also mandated that “two percent per mensem was the maximum one could charge without being a sinner.” [12, 114]

Later, Candesvara would inveigh against “the kaarita type of interest, i.e. interest fixed by the parties themselves probably because that exposed the debtors to all kinds of mechanizations by creditors and hence he said that such interest could be charged only in emergencies (aapat kaala) where the borrower himself thought that in spite of the high rate of interest it would still be in his interest to take a loan.” [12, 115] This concern for usury remained a continuing concern.

Elsewhere, “Devana Bhatta could not ignore the prevalence of these types of interest but tried to put some check on exploitative rates of interest. He concludes that kaalika interest is prohibited if it is five per cent per mensem or above; kaayika involving excessive physical pain is prohibited and interest upon interest i.e., cakravrddhi” (compound interest) was often banned by customary law. [12, 115]

“It must be pointed out that Brhaspati and Katyayana both sought to prevent the possible exploitation of poor debtors. Katyayana said that if a creditor troubled a debtor who wished to seek the protection of the court, he would lose his right to recover and would be liable to pay double the amount of as fine. Brhaspati also prohibits a creditor from employing coercive measures against a debtor if there is a dispute”. [12, 120]

In short, usury as a way of life is condemned. Exorbitant (atyarthaadhika) rates are not sanctioned by dharma. [12, 115]

Pautaavam (Weights & Measures)

One area of particularly close regulation was in the system of weights and measures. From the Vedic era down to the early medieval period, there was remarkable consistency in weights and their enforcement. Some find remarkable consistency dating back even to the Sarasavati Sindhu (Indus Valley). Regardless, Pautaavam (Weights & Measures) was a pivotal part of commerce in any era.

“The Chief Controller of Private Trading kept a watch over merchants, by inspecting periodically their weights and measures and ensuring that they did not hoard, adulterate or add excessive mark-ups {4.2.2., 19, 22, 28}” [4, 76] Crown commodities could be sold by private merchants, after paying a fee {2.16.9}. [4, 76]

Contrary to contemporary concern about quality, and the alleged ‘sanctity of contract’, business dealings between merchant and buyer were expected to be honourable, and safeguarded by the state. “Weights and measures used by merchants were periodically ins-pected; use of unstamped measures was a punishable offence {2.19.41}. The specifications for making standard weights and mea-sures and their sales prices were laid down” [4, 86]

Finally, there was a public interest in this monitoring beyond the short term. The same government department was expected to plan for long-term needs and guard against shortage and deprivation.

“The Chief Controller of State Trading was responsi-ble for the equitable distribution of local and foreign goods, buffer stocking, sale of Crown commodities and public distribution. He could appoint private traders as agents for the sale, at fixed prices, of Crown commodities or sell them direct to the public through state-owned retail outlets {2.16.8, 14-16}.” [4, 76]

For those bemoaning the existence of allegedly non-performing Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs), it was quite clear that petty traders, wealthy merchants, well-organised srenis, and government vendors all operated to serve the needs of the public. Rather than profit being at the heart of this, service was, with profit being the (positive) externality of this activity.

Important Texts

Dharmasastra

Raajasaastra of Brahma

Arthasaastra of Brhaspathi

Arthasaastra of Kautilya

Sukra Neethi

Vidhura Neethi

Key Personalities

Anaathapindika

Tapusa & Bhallika

Saddaalaputta

500 Svamis of Ayyavolu

House of Jagat Seth

Conclusion

The merchants Tapusa and Bhallika of Balkh (Valhika) were among the early lay disciples of The Buddha. They are credited by Xuan Zhang with spreading the Dhamma throughout Central Asia. Whether they were Indian or not, they certainly were Indic merchants. Thus, from Anaathapindika down to the Ambanis, there has been a long and storied tradition of Indic Commerce. While the contemporary kirana owner may be facing extinction with the emergence of multi-brand/mass retail, hope remains that the tradition of Vaanijyam will once again stand the test of time. Indeed, even in the ancient-most days, merchants had a key role in spreading and sustaining Dharma.

In some historical cases, communities such as the Veera Balija Naidus of Andhra found the need to arm themselves in guarding their medieval trade caravans. As they began financing and supplying rulers with soldiers, they began to be inducted in the aristocratic hierarchy, eventually becoming Naayak kings in Madurai, Thanjavur, Gingee, and Sri Lanka. The 500 Svamis of Ayyavolu are said to have been from this community, and financed trade throughout South East Asia through their guilds (srenis).

“The Ainnurruvar, often styled the Five Hundred Svamis of Ayyavolepura (Aihole), were the most celebrated of the medieval South Indian merchant guilds. Like the great kings of the age, they had a prasasti of their own which recounted their traditions and achievements. They were the protectors of the Vira-Bananjudharma, i.e. the law of the noble merchants, Bananju being obviously derived from Sanskrit Vanija, merchant. This dharma was embodied in 500 vira-sasanas, edicts of heroes. They had the picture of a bull on their flag and were noted ‘throughout the world’ for their daring and enterprise. They claimed descent from the lines of Vasudeva, Khandali and Mulabhadra, and were followers of the creeds of Vishnu, Mahesvara and Jina.” [9, 300-301]

“Among the countries they visited were Chera, Chola, Pandya, Maleya, Magadha, Kausala, Suarashtra, Dhanushtra, Kurumba, Kambhoja, Gaulla, Lata, Barvvara, Parasa (Persia), and Nepala…they filled the royal treasury with gold and jewels, and replenished the kings’ armoury; they bestowed gifts on pandits and sages versed in the four samayas and six darsanas. There were among them the sixteen settis of the eight nads, who used asses and buffaloes as carriers, and many classes of merchants and soldiers, viz. gaveras, gatrigas, settis, settiguttas, ankakaras, biras, biravanijas, gandigas, gavundas, and gavundasvamis.” [9, 301]

Thus, we see here how Commerce began to detach itself from not only varnashrama dharma, but also desa dharma. In some cases this was to the benefit of society-at-large, but in others, not so much.

Whether the modern stereotype of intrepid businessmen or stolid shopkeepers is due, it is clear that ancient merchants, traders, and commercialists were expected to hold themselves to a higher standard. The dharma was not a mere written letter to pay lip-service, but a complete way of life ensuring reciprocal duties between citizen and king, employee and employer, and consumer and merchant. Great business communities, particularly from Gujarat and Punjab have managed to do business everywhere in the world. From Asia to Africa and North America to South America, virtually no continent is untouched by the modern Indic merchant. Menons and Memons, Aroras and Amils, Lohanas, Lahotis, and Komatis, all have made their stamp on the Global Economy. Post-liberalisation communities such as the Patels and Nadars have become internationally recognised, and now SC entrepreneurs have achieved impressive strides. While this success transcending backgrounds should be celebrated, solely counting of dollars and cents has set aside common sense.

Indeed, while it’s important to create an environment in which entrepreneurs (different from capitalists) can succeed, the national & civilizational interest cannot be suborned.

“The Indian princes opposing the European marauders not only failed to match the European technology of warfare on the sea and land, they could not create a state structure that would depend on the credit of a mass of loyal subjects rather than that of a small group of financiers who loyalty would shift as they saw the fortunes of their erstwhile patrons seriously threatened, or would actively conspire” [5, xvi]

Contrary to popular opinion, traditional business communities alone were not to blame. Reprobation goes to the very highest levels of government. Ironically, those most enthusiastic about varnashrama dharma are not always inclined to correctly observe it.

“in the eighteenth century, perhaps because of the growing political activities of the Marathas, a new class of sahukars, mainly brahmans, emerged under the patronage of the Peshwas, which dominated the political and economic life of the Maratha country for several decades. Among the major banking houses, mention may be made of Tulshibagwale, Chiplunkar and Khasgiwale of Pune; Biwalkar of Kalyan; Dixit-Patwardhan of Nasik; and Vaidya of Wai (Satara). “[5, 105]

“The Peshwas being Brahman by caste, enjoyed a privileged position in the society, which brought them many social, political and monetary advantages. One peculiar institution called ramana was developed by the Peshwas through which distribution of dakshina—money reward—to Brahmans in the month of Shravan was organized on a large scale; for this the royal treasury was depleted and to fill it, and even for making payments to the civil and military servants, money was borrowed from the sahukars. In 1796-97, Rs 245, 990 were distributed as dakshina among 3,851 at various gates of the city, including the royal palace.” [5, 107]

“As the Indian financiers came gradually to perceive that the naval and military organization of the Europeans, and in parti-cular the British, were superior to those of the local rulers, their loyalty shifted: they thought that their future would be better protected if they sided with the victor rather than the power about to be defeated through the might and wiliness of the farangis.” [5, xvi]

This, of course, goes against the grain of Dharmasaastra. Apastamba Dharmasutra states the following:

“Trade is not sanctioned for Brahmins…He should not be overly attracted to this way of life and give it up when he finds his legitimate livelihood.” [11, 59]

Rather than casteists of all castes castigating other castes, perhaps the time has come for all castes to critique themselves. Criminal negligence & complicity in colonial history can no longer be denied. Those obsessed with varnashrama dharma must first account for whether it was being correctly observed, and those wishing to eliminate caste for class or even caste and class, must also explain how their system will be significantly more humane and eco-friendly. That is the true loss to honest commerce: the absence of maanava-tattvam.

One thing both modern capitalism and medieval Indic commerce forgot was the human element. Usury and bilking others became a way of life. The very thought of “honest commerce” has become a risible proposition. On the flipside, the fabian license-permit-quota raj did not make things any easier for dharmic businessmen, and the less said about the treatment of workers the better. Communism, of course, is a sheer disaster, leading the consensus to break to neo-liberalism. But today, Bangalore is not just the software city of India, it is also the Bengaluru of Bellandur lake. Rather than Maharashtra’s status of being the most-industrialised state in India being a matter of pride, it is also a matter of water distress for Marathwada and the hinterland of the state.

Rather than foreign liberal “economics” and unsustainable development, it is Dharmanomics and Dharmic Development that can make true Vaanijyam a wealthy a viable proposition once again. Blaming only business or blaming only government or blaming only one class or blaming only one caste, is no longer viable. The time has come for serious people to look for serious solutions to common problems, as a common society. Constantly shifting blame to one class or another or one caste or another is not a recipe for success, but a recipe for disaster. And it is increasingly one that is taking us not only to economic and national disaster, but environmental disaster as well.

Until our principles of prosperous Dharmic business are rediscovered, until industry or business cease to be purely about a number but also about people, then the true tradition of Classical Indic Commerce, with all its profitable achievement and sustainable wealth, will remain a distant dream.

References:

- Vidura Niti

- Sukra Niti

- Sarasvati, Chandrasekharendra (Svami). Hindu Dharma: The Universal Way of Life. Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. 2015

- Rangarajan, L.N. Edit, Kautilya. The Arthashastra. New Delhi. Penguin. 1992

- Bagchi, Amiya Kumar. Money & Credit in Indian History—From Early Medieval Times.New Delhi: Tulika Books. 2002

- Basham, A.L. The Wonder that was India. Delhi: Rupa. 2010

- Majumdar, R.C. Ancient India. Delhi: MLBD. 2003

- Sastri, K.A. Nilakantha. Age of the Nandas & Mauryas. Delhi: MLBD.1996

- Sastri, K.A.Nilakantha. A History of South India. New Delhi: Oxford. 2015

- SarDesai, D.R. India: The Definitive History. Philadelphia: Westview Press. 2005

- Olivelle, Patrick. Dharmasutras. Delhi: MLBD. 2003

- Mathur, Ashutosh Dayal. Medieval Hindul Law. New Delhi: Oxford University. 2007

![[Reprint Post] Dharmic Development](https://indicportal.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/oordhva-150x150.jpg)

![[Reprint Post] Culture: The Cure for Stupidity](https://indicportal.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/3085064-Wendell-Pierce-Quote-The-role-of-culture-is-that-it-s-the-form-150x150.jpg)

![[Reprint Post] Origins of Indian Stupidity](https://indicportal.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/originsofstupidity-150x150.jpg)