Some aspects of Indic Epistemology may be arcane and little-discussed, while others may in fact be well-known and occupy centre-stage attention. When dealing with a living and breathing tradition, it becomes imperative to preserve the core traditional concepts while finding ways to ensure it remains relevant and responsive to the needs of the general population, whether traditional or modern. Our next topic remains one of the most relevant of Traditional Indic Knowledge Systems known to man.

After our consecutive articles on Sthaapatya Veda and Dhanur Veda (and our previous discussion of Gandharva Veda), we round out the 4 Upavedas with today’s Post. It is the first in a New Series on Classical Indic Medicine, better known as Ayurveda.

Introduction

Classical Indic Medicine is both ancient and modern. This is because ‘classical’ should not refer to a specified time period, but rather, a specific Saastric and ultimately Vedic tradition that is living and lived, even to this day. But how does one separate the incantations from the practical medicine? Should one separate them? Irrespective of the place of mantra and tantra, Ayurveda is most definitely a practical science (vijnaana).

In order to understand its value today, one must engage in holistic study and an open mind. While it is true that Western Civilization separates the sacred from the secular, Indic Civilization does not. Science, and indeed, knowledge itself is sacred. That does not mean doctrine cannot be challenged. It does mean that the tradition itself must be treated with respect and with the intention of preserving its aim: the betterment of mankind.

There are many scientists and even “swamis” today, who wish to strip Yoga (and eventually Ayurveda) of its “cultural trappings” and “deliver it as absolute science“. But this is a formula for absolutism, scientism, and absolute scientism. Authority is not given to them to take a tradition they don’t have a monopoly over and to commercialise it in order to increase followership. Similarly, it is understandable if board-certified Medical Doctors wish to emphasise the purely practical aspects regarding diagnosis and treatment. But rather than mining the tradition for personal gain while crediting “Western Science”, this can be done by simply stressing that research papers and treatments will emphasise only the ‘scientifically’ confirmed aspects of Ayurveda, while crediting the Ayurveda tradition as a whole.

Rather than referencing deities and other sacred figures, the long list of historically-confirmed, competent physicians, surgeons and medical authorities out of India can be cited instead. Doctors need not be associated with “pseudo-science”, Ayurveda need not be digested, and patients can benefit from effective treatment. Above all, if the Chinese have retained certification standards for acupuncture, and have ensured it has been recognised as rational alternative treatment, there is absolutely no reason India cannot do at least the same for Ayurveda.

Some time ago, a traditional Telugu Pandit spoke on how modern Western medicine (“allopathy”) treats the symptom, not the cause. One symptom is treated in one part of the body, but it ends up pushing the problem to another part of the body, and so on. The net result is there is only temporary ameloriation with a potential pandora’s box of lifelong side effects.

Along with patients, Doctors themselves are now finding it difficult to navigate a hostile space of corporatisation of care, universalisation of wage slavery, and multiplication of insurance forms. What was once an august and respected profession has been reduced to “damned if you do and damned if you don’t”. As a result, neither doctor nor patient nor family member (nor society at large) is satisfied with outcomes. Profit margins looms large, medical student loans even larger, and patient wellness a distant afterthought.

If medicine is to return to a greater degree of effectiveness, if the medical profession is to return to its former dignity, and if medical care is to return to the topmost priority, it may be time to get back to our roots. Ayurveda can certainly exist alongside Allopathy. The task at hand is determining whether & how it can enrich the body of ‘modern medicine’ without itself being digested. For that, the tradition itself must be studied with the emic lens.

Purpose

Aayusho vedah Ayurvedah

The science that deals with Ayus (life) is Ayurveda [7,1]

Ayurasmin vidhyathe anena vaayurvindathyaayuvedah (Sushruta Samhita 1.14)

Ayurveda is that which deals with Ayus (life) or promotes lifespan

According to Acharya Charaka, “The term ‘Ayus’ stands for the combination of the Sareera (body), Indriya (sense organs), Satva (mind) and Atma (soul). [7,2]

There are a number of synonymous that are often used for Ayus (life) and Ayurveda (Shakha, Vidya, Sutra, Jnana, Shastra, Lakshana, and Tantra).

Both Charaka and Sushruta write that there 2 objectives for Ayurveda:

- Preservation of the health of the healthy

- Treating the disease of the diseased [7,4]

Interestingly, Charaka himself writes the following on who is eligible to study Ayurveda

Ayurveda is to be studied by the Brahmans for providing benefit to all the creatures, by the Kshatriyas for protection, and by the Vaishyas for earning livelihood. In general, the Ayurveda is to be studied by all for the attainment of virtues, wealth, and pleasure. [7,4]

In fact, provision is made for the study of Ayurveda for all four classes of orthodox Hindu society. Only mantra was linked to upanayana. Health truly is wealth, and this form of wealth is naturally sought out by all. A healthy society can perform its duties and pursue the purusharthas without problem.

Terminology

- Ayurveda—Science of Life

- Aarogyam—Health

- Jeevanam—Life/living

- Maranam—Death/dead

- Rogam/Vyaadhi—Disease

- Aushadham—Medicine

- Vaidya/Bhishaj—Medical Doctor/Physician

- Anuvaidyaa/Parichaarikaa—Nurse

- Sutra Sthaana—General Principles

- Shalyatantra—Surgery

- Maanasa Roga—Psychiatry

- Stri Roga—Gynaecology

- Bhruna—Fetus

- Ulbam—Fetal fluids around the womb

- Kaumarabhritya—Pediatrics

- Rasa Sastra/Rasayana—Chemistry/Science of Rejuvenation

- Kaaya Chikitsa—Internal Medicine

- Sareera Rachana—Anatomy/Physiology

- Sareera/Vapus—Body

- Marma—Vital Parts

- Seera/Seersa/Masthakam/Moordhana—Head

- Bhaala/Phaala—Forehead/Middle of Forehead

- Mastishka—Brain

- Pramastishka/Seerobrahma/Moordhaa—Cerebrum

- Nimastishka/Seerobiloma—Cerebellum

- Thaalu—Palate

- Austha—Lips

- Mukhamandala/Vadhanam—Face

- Mukham/Aananam—Mouth

- Naasika—Nose

- Nayanam/Netram/Lochanam—Eye

- Hastham—Hand

- Kanta—Throat

- Greeva—Neck

- Uras—Chest

- Udaram—Abdomen

- Nabhi—Navel

- Jangham/Ooru—Thigh

- Paadham—Foot

- Phupphusa/Kloma—Lungs

- Tvacha/Charman—Skin

- Kesha/Loman—Hair

- Raktha/Rudhira/Asrj/Loha—Blood

- Sampruktham—Small

- Chikitsa—Treatment

- Chikitsam—License to practice medicine or pharmacy

- Chikitsaalaya—Hospital

- Yantra/Varthee—Instruments

- Kartaarika— Scissors

- Phenaka—Soap

- Ushna—Hot

- Shaithyam—Cold

- Aapannah—Afflicted

- Asvastha—Sick

- Jvara/Takman—Fever

- Vedhana—Pain/Ache

- Apasmaara—Epilepsy

- Atisara/Aasraava—Diarrhea

- Kaasa—Cough

- Balaasa/Yaksma—Tuberculosis

- Jalodra—Dropsy

- Aksata—Tumour

- Kilaasa—Leprosy

- Krimi—Micro Organism

- Immunity—Vaishnavi Shakti

- Inherited Disease—Ksetriya

- Ahiphena—Opium/pain-medication

- Tambhaku—Tobacco

- Spandanam—Throbbing/vibration

- Nischayothanam—Trickling/oozing

- Thoyam/Neeram/Jalam—Water

- Satvaara—Urgent

- Vishraanthi—Rest

- Bhaadhitha—Patients

- Vranitaagaara—Infirmary/Room for wounded

- Sootikaagaara—Labour room

- Kumaaraagaara—Nursery

Theoretical Foundations

The origins and foundations of Ayurveda are significant not just from an epistemological perspective, but also from teleological perspective. In the present time, it is fashionable to deconstruct and separate integrated practices and bodies of knowledge into hermetically sealed subjects. But knowledge is itself a continuum. Each subject can at some point in time or another have an impact on others, as seen in the Sulba Sutra. In the push to make it more digestible, the Veda is slowly but surely being taken out of the Ayurveda. It is therefore with the Breath of ParaBrahman that we must begin.

Veda

With Ayurveda, ICP’s tour of the 4 upavedas is complete. But which upaveda is attached to which Veda? This question has been a controversial one since almost the beginning of time. One school asserts that Ayurveda is an outgrowth of Atharva Veda, Sthaapatya Veda an outgrowth of Yajur, and Dhanurveda an outgrowth of the Rig. Another holds that Ayurveda emerged from the Rig Veda, Dhanurveda from the Yajur Veda, and Sthaapatya Veda emerged from the Atharva Veda. Both views correctly assert the natural outgrowth of Gandharva Veda from Saama Veda. For the sake of consistency and simplicity we will simply reassert the second one and put the matter to rest:

- Ayurveda — Rig Veda

- Dhanurveda — Yajur Veda

- Sthaapatya Veda — Atharva Veda

- Gandharva Veda — Saama Veda

The rationale behind this is that Ayurveda itself has alternately been referred to as either the fifth veda, or even as preceding the Atharva veda. Further, Dhanurveda’s association with Yajur makes sense, given the traditional concept of war as sacrifice. Ultimately, what matters is consistency and the connection of Ayurveda to and its theoretical foundation in the Chaturveda itself.

The science of medicine made great strides after the Vedic period, particularly in the era of consolidation, 200 BCE to 200 CE. There was some information on medicine in the Rig-Veda and considerably more in the Atharva Veda.” [2, 114-5]

Furthermore, it should be noted that the approach to learning was systematic.

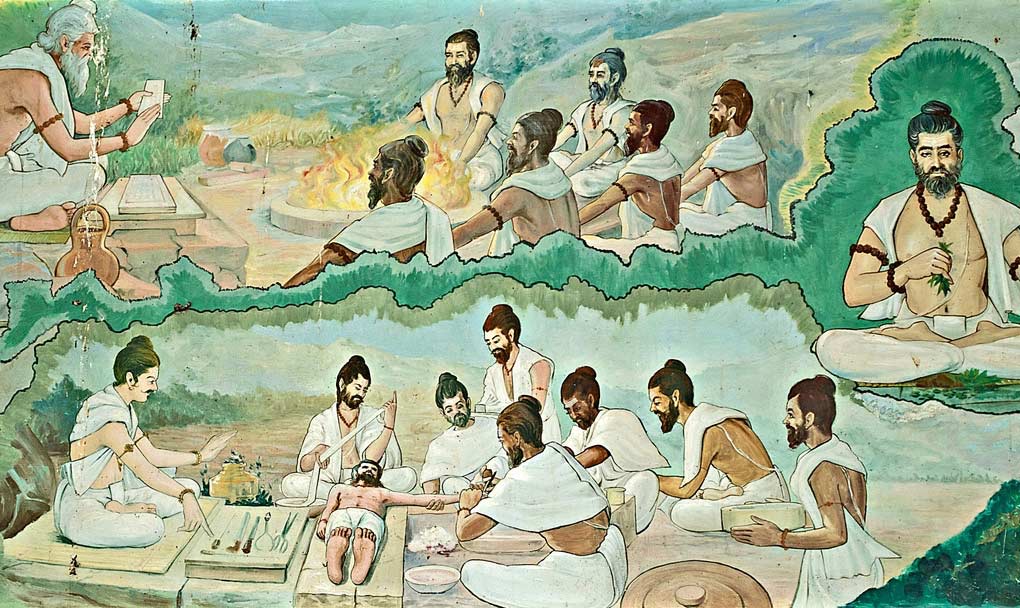

“Schools for the systematic study of medicine were established around the time of the Upanishads.. That was the time when ayurveda (the science of well-being and longevity) developed and, because of its importance, given the status of a semi-Veda or Upa Veda of the Atharva Veda. Of the eight divisions of ayurveda, only one now dealt with the evil spirits, whereas for most practitioners, medicine was rational, not magico-religious.” [2, 115]

The Descent of Ayurveda (Ayurvedatarana)

Ayurveda was said to have been conceived by the self-born Brahma prior to even creating the universe. The original composition was in 100,000 stanzas arranged in 1000 chapters. After evaluating the lifespan and intellect of human beings, Brahmadev further divided it into 8 branches.

“Even so, the origins of ayurveda were regarded as divine. The god Indra was believed to have taught the science of medicine to Punarvasu Atreya, who was regarded as the fount of wisdom in the field of medicine. Atreya taught at Taxila University at the time of the Buddha. Six pupils of Atreya compiled all that they learned from the master in a medical encyclopedia. Of the different versions, only those of Bhela (Bhela Samhita survived only partly in South India) and Agnivesa have survived. During the era of consolidation, the well-known Caraka Samhita was compiled. It was based on the compilation of Agnivesa in its final form.”[2,115]

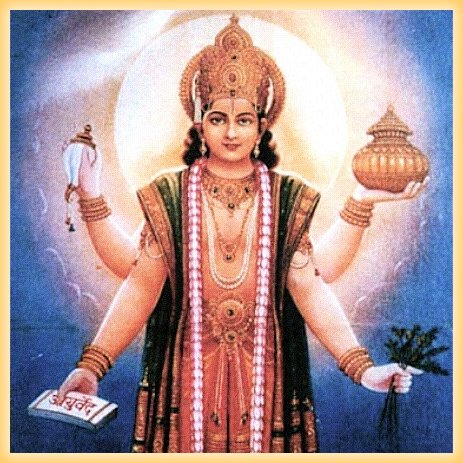

So where do we begin? Do we begin with Brahma who taught it to Indra? Indra who taught it to Atreya? Or Atreya who taught it to Agnivesa? Perhaps it is best to start with the deity Dhanvantari who presides over Ayurveda.

Dhanvantari

Dhanvantari is the patron Deva of Ayurveda. Per the Ramayana, he emerged during the Koorma Avatara of the Satya Yuga, while the Suras and Asuras were churning. As the bearer of Amrtham (nectar of Immortality), it is unsurprising that he assume the place of the giver of life. Interestingly enough, Health and Food are intrinsically connected. If diet and nutrition are associated with wellness today, Ayurveda’s role cannot be minimised. Indra who taught the Science of Life to Dhanvantari, also taught it to Kashyapa, Vasishta, Atri and Bhrigu (who in turn taught it to their descendants for the benefit of mankind). [7, 13]

But to understand all of this, one must evaluate the roles of the two most important historical Personalities of Indic Medicine: Charaka and Sushruta.

Charaka

Charaka is arguably the most foundational author on Traditional Hindu Medicine.

“The Caraka Samhita was the most elaborate treatise on medicine. It had eight divisions, each of them further divided into several chapters. It deal with fetal generation and development, human anatomy, and the bodily functions depending on the three bodily humours known at that time—vayu (breath or wind), pitta (gall), and kapha (phlegm). The treatise discussed the basis of the tridosa (or three-humors) theory. The work listed about fifty groups of medicines working on the various systems.” [2,115] It was a compilation of Agnivesa’s work that resulted in the composition known as Charaka Samahita. This contains 8 sthanas, 120 chapters, and 9295 sutras.

Notable Facts

- Bheshaja Chatushka encapsulates the general overview of health and medicine

- Svastha Chautshka explicates preventative and general medicine

- Nirdesha Chatushka covers effective treatment as well as the trivarga

- Kalpana Chatushka discusses treatment

- Roga Chatushka covers various conditions and illnesses

- Yojana Chatushka treats with human classification and corresponding ailments

- Annapana Chatushka analysis a wide range of topics, especially diet.

- This work was translated into Persian then Arabic. It is found in Latin translations of Avicenna as Sharaka Indanus.

Sushruta

“What Caraka did for medicine, Susruta did for surgery.” [2,116] Considered by most to be the son of Maharishi Vishvamitra (though some say his veterinary medicine teacher Salihotra was), Sushruta is often called ‘The Father of Surgery’. The Sushruta Samhita records that Brahma gave Ayurveda to Prajapati, who gave it to the Ashvins, who gave it to Indra, who gave it to Dhanvantari. Dhanvantari had 12 disciples, who are as follows: Aupadhenava, Paushkalavata, Kankayana, Vaitarana, Karaveerya, Bhoja, Gargya, Aurabhra, Gopura Rakshita, Nimi, Galava, and Sushruta. The association with Dhanvantari himself demonstrates the antiquity of Vrddha Sushruta. Though presently dated to 1000 BCE, it is more likely based on this association that he hails from the ancient-most days of the Aryavarta. [7, 40]

By some accounts there are said to be 2 Sushrutas, of which the main is Vrddha (old).There were other commentators such as Aurabhra, Gopurarakshita, Vrddha Jivaka, Ksharapani, and Videha. In conjunction with them are the 3 Schools of Ayurvedic Thought: Atreya, Dhanvantari, and Bhaskara.

Sushruta hails from the Dhanvantari school. His Samhita contains 6 sthanas (sections), 186 chapters, and 8300 Sutras. There were numerous commentaries on this treatise, with Jejjata’s now lost work as the earliest. Others were the Brihat Panjika of Gayadasa, Bhanumati of Chakrapanidatta, Sushrutartha Sandipana of Haranachandra, Tippana of Brahmadeva, and Nibandha Samgraha of Dalhana from Kashmir.

Notable Facts

- Provides framework of surgery as focal point

- Uses and faults of surgical instruments

- Instructions regarding Operative procedures

- Disease classification and Medical Vocabulary

- Deals with medical education and stresses cleanliness.

- Tridosha System

- Classification of Drugs and curative methods

- First Principles. Vital points (marmas), along with Rasayana

- Translated into Arabic as Kitab-Shah-Shun-al-Hindi & Kitab-i-Susrud.

Key Concepts

Approach

The Charaka Samhita asserts the following:

Dharmaartha kaama mokshaanaam arogyam moolam uttamam |

Health is the chief basis for the development of the ethical, economic, epicurean, and spiritual sides of man. [1]

As such, the wealth of a country depends upon the vitality of its people (along with the natural resources). Therefore, Acharya Charaka asserts that the physician should not be motivated by selfish reasons or worldly pleasures. His occupation is meant for the relief of humanity’s suffering. Modern medicine, in its drive for affluence and profit, has diverged from this ancient Indic approach. It is time to get back to the basics.

Traditionally, there were 8 branches (Ashtanga) of Ayurveda . These were as follows:

1.Kayachikitsa (Internal Medicine) 2. Shalakya Tantra (supra-clavicular diseases) 3. Shalyatantra/Shalyapharitrika (Surgery) 4. Vishatantra (Toxicology) 5. Kaumara-bhrtya (Pediatrics, Obstetrics, Gynaecology) 6. Rasayana (Science of Rejuvenation) 7. Vajikarana (Sexology), and Bhuta Vidya (mental illness/invisible agents).[7,5]

While 7 of these were what we would consider serious science, the 8th is often associated with mantra, tantra, and yantra and branded as “demonology”, in an attempt to discredit all of Ayurveda. But this is unfair. Concerns about “invisible agents” and malign influences and energies existed in all societies (including the western) at some point in time or another. These ‘occult’ aspects can be set aside by scientists. Indeed, the Ayurveda tradition itself which originally associated Psychiatry with Bhuta Vidya eventually developed the specialised field of Manasaroga for Mental Illness. Ashtanga Ayurveda eventually became the Sodasa Ayurveda, with 16 branches.

- Sutra Sthaana (General Principles)

- Kayachikitsa (Internal Medicine)

- Shalakya Tantra (Supra-clavicular diseases)

- Shalyatantra/Shalyapharitrika (Surgery)

- Agadatantra (Toxicology)

- Kaumara-bhrtya (Pediatrics)

- Rasayana (Science of Rejuvenation)

- Vajikarana (Sexology)

- Sareera (Anatomy-Physiology)

- Dravyaguna (Pharmacology)

- Bheshajakalpana (Pharmacy)

- Rasa Sastra (Chemistry)

- Nidhaana/Rogavijnana (Pathology)

- Svasthavritta (Preventitive & Social Medicine)

- Manasaroga (Psychiatry)

- Prasutitantra/Striroga (Obstetrics & Gynaecology)

Tridosha

As is now increasingly well-known, the tridosha system is central not only to Ayurveda but to well-being. These doshas are Kapha (oily, smooth, soft, sweet, thick, heavy, cool), Pitta (hot, keen, liquid, pungent, sour) and vaata (dry, light, restless, copious, transparent). [1, 64] Although this system seems simplistic, its connection to diet, and in turn, diet’s connection to health, make it elegant and ultimately valid. Coexistence of all 3 is known as sannipaata, and of two is called samsarga [1, 72]

The concept of Tridosha, that is the 3 humours, ultimately find their origin in the panchabhutas (air, earth, ether, fire, water). Air is notable specifically in the concept of wind, which drives various bodily functions such as peristalsis, etc:

“The bodily functions were maintained by the five ‘winds (vaayu): udaana, emanating from the throat, and causing speech; praana, in the heart, and responsible for breathing and the swallowing of food; samaana, fanning the fire in the stomach which ‘cooked’ or digested the food, and dividing it into its digestible and indigestible parts; apaana in the abdomen, and respon-sible for excretion and procreation; and vyaana, a generally diffused wind, causing the motion of the blood and of the body generally. The food digested by the samaana became chyle, which proceeded to the heart, and thence to the liver, where its essence was converted to blood. The blood in turn was in part converted into flesh and in the process was continued through the series fat, bone, marrow and semen; the latter, when not expelled, produced energy (ojas), which returned to the heart and was thence diffused over the body. This process of metabolism was believed to take place in thirty days.” [8, 498]

In tandem with the 5 vayus (associated with vaata) are the five agnis (associated with pitta). These are paachaka (abdominal area), ranjaka (liver and spleen), saadaka (heart area), alochaka (ocular functions) and bhrajaka (dealing with skin). These various derangements deal with various parts of the body affecting various organs. [1, 69]

Finally, there are 5 varieties of kapha: kledaka (abdominal area), avalambaka (heart area), bodhaka (tongue & palate), tarpaka (in the head), and slesaka (in the joints). All of these are related to heaviness, dullness, and torpor. [1, 70]

While this may not necessarily gel with modern ‘scientific’ notions, it nevertheless is notable for its thoroughness and holistic conception of the body and bodily functions. Tridosha is the central construct through which harmony is maintained within the body. Rather than merely treating the symptoms, it attempts to understand causality. The doshas do not alter spontaneously via various nidhaanas (causes), but are affected by dhaatu-saamya (or elemental equilibrium) as the goal. Tridosha provides a guiding principle to not only healing and preventative care, but verily the very lens through which the vaidya considers how to proceed.

Vaidya

The vaidya’s dharma was to determine and treat the cause for dhaatu-vaisamya, or imbalance that leads to disease.

“The physician was a highly respected member of society, and the vaidyas rank high in the caste hierarchy to this day. The rules of professional behaviour laid down in medical texts remind us of those of Hippocrates and are not unworthy of the conscientious doctor of any place or time.” [8, 500]

Interestingly, Hippocrates followed Charaka’s invocation of the gods (Apollo in his case) prior to the oath.

“Hippocrates is called ‘Father of Medicine’, because he first cultivated the subject as science in Europe, is shown to have borrowed his Materia Medica from the Hindus.” [7, 178]

Here is the relevant quotation from Charaka:

“If you want success in your practice, wealth and fame, and heaven after your death, you must pray every day on rising and going to bed for the welfare of all beings, especially of cows and brahmans, and you must strive with all your soul for the health of the sick. You must not betray your patients, even at the cost of your own life….You must not get drunk, or commit evil, or have evil companions…You must be pleasant of speech…and thoughtful, always striving to improve your knowledge.

When you go to the home of a patient you should direct your words, mind, intellect and senses now where but to your patient and his treatment….Nothing that happens in the house of the sick man must be told outside, nor must the patient’s condition be told to anyone who might do harm by that knowledge to the patient or to another.” [8, 500]

Medical education was also given due consideration. Aspiring physicians were exhorted to select a proper preceptor, while instructors themselves had the right to reject pupils. Per even the ancient Sushruta, all four classes could be admitted as pupils (though mantra reserved for 3). Training would last 6 years and would be based on an approved text, with a requirement of mastering both medicine and surgery. Character was critical and it was deemed that all persons were not necessarily suited to be students of medicine. Criteria was stipulated for teacher and student alike.

His appearance should be humble and his mind pure and guileless. He should be polite in his speech and friendly to all living beings and he should have an attendant of good character. [1, l]

Unlike today, there was no strict dividing line between medicine and surgery. Sushruta recommended that all students of medicine be taught both, and Charaka recognised surgery as an integral part of treatment. [1,xxi] Furthermore, it was imbued with philosophy. Ayurveda is said to draw from the Nyaya-Vaiseshika darshana. As such, 3 pramanas were considered valid: aaptopadesa (sabda of the wise), pratyaksa (perception), and anumaana (inference). [1, xxiv] The Atharva Veda itself is often considered the first text treating with medicine.

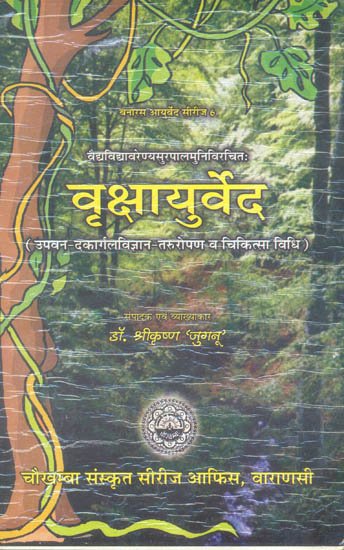

Veterinary medicine (Saalihotram), named after Sushruta’s teacher, was also practiced with specialties (Asvaayurveda by Sage Saalihotra & Hastyaayurveda by Maatanga), and pharmacopeia necessitated a knowledge of plants through vrksha-ayurveda (eponymous text by Surapaala).

The vegetable products are of four kinds: vanaspati, viroodh, vaanaspatya and osadhi. Trees or plants that produce fruit (but not flowers) are called vanaspati; those that produce both fruit and flowers are vaanaspatya; those that perish upon the ripening of their fruit are osadhi, while creepers are called viroodh. [1,110]

Free hospitals were common throughout ancient India, and were maintained by the donations of private citizens. Royal hospitals & veterinary hospitals also existed, maintained by the state. Pharmacology is a section of its own and could be an article to itself. Suffice it to say, there is an exhaustive list. Of note is that Charaka provides 50 classes of medicine, in 23 different forms. [1, 122]

Medicine

Both Charaka and Sushruta Samahitas have a section called Sareera Sthaana (anatomy). This is the mainstay of medicine as it effectively serves as the geography of the body. Per Ayurveda: a male attains full development at 25 years and a female at 16 years. [1, 93]

Embryology is a standard section, with much discussion over the the male and female generative contributions. Osteology is another. An interesting point here is that a total of 300 bones are listed (as opposed to the present standard of 206). What is the reason for the additional? Teeth, nails and cartilage (which hardens) were included in the count. Here is a listing of key names not named above:

bahu (arms), sakthi (legs), antaraadhi (trunk), dantha (teeth), ulookhala (sockets), anguli (phalanges/fingers), parsni (heels), gulpha (ankles), manika (wrists), aratni (forearms), jangha (thighs), jaanu (knee-caps), koorpaka (elbows), amsa-phalaka (shoulder blade), aksaka (collar-bone), sroni-phalaka (hip blades), prstha-gataasthi (back-bones), paarsvaka (ribs), jatru (wind-pipe), taaloosaka (palate), hanu-asthi (chin), sankha (temples), kapaala (skull). [1, 7] Bones and joints are categorised under various types. Muscles (snaayu) are treated as a separate section). A woman has 20 more muscles than a man (who has 513). [1, 19] Dhamanis are nerves and ducts, while the stomach (aamaasaya) and intestine (pakvaasaya) are important considerations as well.

The Ashtanga Hridaya lists 231 diseases, of which 94 are ophtalmic, 25 ear, 18 nasal, 75 oral, and 18 related to the head and skin. [7, 63] Diagnosis (vimaana) of these and examination are dealt with in Charaka Samhita under the sections Nidhaana, Vimaana, and Indriya. The ten elements of examination are as follows: kaarana (agent), karana (the instrument of agent), kaarya (purpose of agent), karya-phala (effect of agent), anubandha (result to the doer for effect), desa (place), kaala (time/seasons), pravrtti (effort needed for effect) and upaaya (aptitude of agent).[1,90]

Treatment

Urveeruha (vanaspathi), mantra, and karttika (surgery) are mentioned as the 3 pillars of treatment. Vanaspathi as discussed above, deals with medication. Mantra is used for invisible agents (typically for mental illness). And surgery is, of course, obvious. [10,135]

Surgery

Susrutha Samhita first ever English translation directly from Original Sanskrit texts. https://t.co/jOzeKfj0C4 pic.twitter.com/7z1chfd1ff

— Inquisitiv_indian (@Inquisitive_Ind) July 11, 2014

Shalya-tantra (surgery) was considered by many to be the most important branch of Ayurveda. To attain dexterity (yogya) skill was required in 8 types of surgical operations : bhedya (excision), chhedya (incision), lekhya (scarification), vedhya (puncture), eshya (probing), aaharyaa (extraction), visravya (drainage of fluids), and seevya (suturing). [1, 152] Cauterisation, various types of instruments, and different bandages are also stipulated. [1, 162] Arguably the most singularly spectacular contribution emerging from Hindu surgery is the concept of the marma. While this concept is best known in the arena of the martial arts (and used to deadly effect by practicioners of kalaripayattu), they are also foundational to shalya. There are 107 marmas in the human body. Mastery of the marmas is considered to be the hallmark of success in Indic surgery.

“Susruta believed that the navel, surrounded by the tubular vessels (sira), about 700 of them, was central to the body’s functioning. He was known to have used innovative techniques in dissecting the human body, for reconstructing noses and ear-lobes, and for performing abdominal operations and for removing dead fetuses from the body. Susruta Samhita was later translated into Arabic in the eight century CE and translated from Arabic into Latin. In 1897, it was first translated into English by the noted Sanskritist A.F.R. Hoernle. Under Susruta’s tutelage, surgeons learned their skills. Some information is available on the kind of instruments used in surgery. By the first century CE, instrumentation consisted of twenty types of knives and needles, thirty probes, twenty tubular instruments, and twenty-six types of dressing.”[2,116]

Though it is true that orthodox Hindus discouraged unrestricted dissection of cadavers out of respect for the deceased, Vagbhata does make restricted provision for it in the interest of gaining practical knowledge.

Aside from the standard works on Ayurveda, medical insight could often be found in other texts. The National Epics (Ramayana and Mahabharata) contain many details on this topic, as do the Arthasastra and Ashtadhyayi. There were also contributions from other sampradayas within Dharma.

“The science of osteology, in Vishuddamagga, is more extensive than in Sushruta Samhita.” [7, 10] Other Buddhist texts, such as the Mahavagga, Dhammapada, Nikaya, Jataka, Deepavamsha, and Divyavadana also provide insight into medical science. Jain texts also provide expert context. The Bhadrabahu Charita, Acharangasutra, Parishishtaparvata, Trilokavijnapati, Lokavibhaga are all compositions providing medical insight.

Plastic Surgery

“Ancient Indian surgeons were expert at the repair of noses, ears and lips, lost or injured in battle or by judicial mutilation. In this respect Indian surgery remained ahead of European until the 18th century, when the surgeons of the East Indian Company were not ashamed to learn the art of rhinoplasty from the Indians.” [8, 500]

Sushruta Samahita famously describes many different surgerical procedures, the most famous of which is the forehead skin-flap rhinoplasty. Another is the repair of an earlobe through a skin-flap from the neck. Although in the present time these procedures have been reduced to industry “plastic”, cosmetic surgery nevertheless serves a higher purpose in treating burn victims and those suffering from mutilation—with related procedures better described elsewhere. [9,55]

Diet

“Food was also part of the ‘discipline’ in daily living of the Hindu way of life….The peak of ascetic glory was to be able to live on air and water and the perfect ‘yogi’ was revered because he had taught himself to subsist on a mi[n]imum of food. The bogi learnt the pleasures of eating, and descended to eating two meals a day, while the rogi was the gourmet given to self-indulgence and excess which resulted in ill-health. Hence the same word rogi is used for a man sick with disease (from roga=disease).” [6,17]

Classical Indic Cuisine not only managed to balance the needs of the ascetic yogi with the royal bhogi, but also balanced health with taste. Nutrition and satisfaction need not be diametrically opposed. What matters is what you have, how you have it, and how it balances with not only the rest of your diet, but also with the rest of your lifestyle.

“‘There is no disaster in life’ the adult is admonished, ‘if one eats in mod-eration food that is not disagreeable. As pleasure dwells with him who eats mod-erately, so disease is the lot of the glutton who eats voraciously.’ Moderation in Ayurvedic terms is designated tripti, liter-ally satisfaction, but here connoting the appeasement of hunger and thirst. In contrast is atisauhitya meaning overeating to satiety.” [3, 79]

Does this in fact work? Well, as they say, the proof of the pudding is in the eating.

By an elaborate system of dietetics and regimen of life, Indian medicine teaches one how to keep fit, how to preserve carefully the vitality with which one’s organism had been endowed, how to reach old age, how to enjoy a long healthy life. [1,101]

Principles

- Ayurveda promotes the health of humans, as well as all living beings (i.e ashvaayurveda for horse, hasthyaayurveda for elephant, gavaayurveda for cow, and vrkshaayurveda for plants). Veterinary medicine in general is called Saalihotram.

- There are 3 classes of physician and 2 categories. The classes are chadmaachara (pretentious), siddhasaadhaka (accomplished in treatment), & gunayukta (qualified). The 2 categories are praanaabhisaaras (noble & competent bestowers of life) and rogaabhisaaras (ignoble & incompetent destroyers & pretenders).

- Certification is necessary.“Susruta mentions another restraining influence, the need for a permit to practice from the king.” [1, lii]

- Prevention is better than treatment. Do no harm—or at least minimise harm.

- Health is maintained with balance of Tridoshas (Vaata, Pitta, Kapha) via dhaatusaamya (equilibrium orasa,rakta,mamsa,medha,asti,majja, shukra)

- Achara, specifically, Dinachara, Ratrichara, and Rtuchara is the foundation of preserving good health through harmony with natural rhythm (Rta).

- Diet is the best means to preserve health and treat ailments via restoration of dhaatu-saamya. Neither excess nor deprivation in food. Periodic fasting is good.

- Treatment should be holistic and determined after systemic (rather than isolated) examination of the body & background.

- Psycho-somatic illness validates the connection between psyche and body and emphasises the need for holistic healing.

- Pharmacopic treatments should be based on natural products (herbs, foods, natural metals, etc) and not on chemicals. This minimises toxic side-effects from chemical compounds and compound metals compared with natural metals.

- Immunity development is more important than daily germ control. Bacterial contamination should be avoided, but children especially must develop immunity.

- Focus must be on root causes of the ailment, not merely treating symptoms.

- Learn through remembrance, critical thinking, and doing (on objects & vegetables). “Learning by rote, without understanding the meaning of what is thus committed to memory, is like the ass carrying a load of sandalwood and is labour without profit.” [1,xlciii]

- Sushruta: “He who is only trained in theory but is not experienced in practice knows not what he should do when he has a patient and behaves as foolishly as a youth upon a battle field” [1,xlix]

- “His appearance should be humble and his mind pure and guileless. He should be polite in his speech and friendly to all living beings and he should have an attendant of good character.(S.S.I.10)” [1,l]

- Disease (vyaadhi) is classified as: Aganthuka (Adventitious/External Cause), Sareeraka (Physical), Manasika (Mental), and Svabhaavika (Natural). [9. 115]

- Anesthetics like madhya, sammohini, or ahiphena can be used during surgery or episodes of severe pain.

- Courtesy to women is critical, as is due consideration for their demeanor, distinctness, and dignity. Professional demeanor is advisable in interaction.

Application

Presenting principles is easy enough, but how to apply? Application is best understood through teleology.

Presenting principles is easy enough, but how to apply? Application is best understood through teleology.

“The sole aim of Ayurveda is to prescribe diet, medicines and a regimen of life such as, if properly followed, will enable a hormally healthy man to maintain the equilibrium of his dhaatus and one who has lost this equilibrium to regain it, i.e., to advise man how to preserve or secure health (dhaatu-saamya).” [1, xx] Thus, through preventative care, dhaatu-saamya could be secured. Diet was the first prong of this.

While the general rule was to respect the deceased, Sushruta discusses, avagharshana, the process for dissection of cadavers for surgical purposes. [9,54] Nevertheless, sewing and bandaging were to be practiced on wood and clay figures. Gourds and fruits were also to be used.

“Training in puncturing, letting out fluids, etc. was to be given by performing operations on leather bags or bladders filled with water and mud. Scarification was to be practiced on stretched pieces of leather covered with hair. The operation of piercing, as in the opening of the veins, was to be shown on the veins of dead animals or on the stalk of the water lilly.“[1, xlix]

Per Acharya Charaka, “There are three causes of disease…They are: – (1) the excessive [atiyoga], deficient [ayoga], and wrongful [mithya-yoga] administration of sense objects; (2) the climatic characteristics of heat and cold; and (3) the misuse of intelligence (C.S. I. 1.53). While this basis of etiology may appear reductive to our modern eyes (focused primarily on bacteria, virii, etc), there is underlying wisdom. Improper use of sense objects as is now well-documented, very frequently leads to various STI’s, etc. Climate is of course obvious, and misuse of intelligence (prajnaaparaadha i.e. poor judgment seen in poor application of knowledge) is a catchall. Furthermore, one comes to see that nidhaanas don’t produce disease directly, but are triggered in an environment of dhaatu-vaisamya.

Inoculation was, of course, also familiar to ancient Ayurvedic practioners. Beyond the standard evidence of testimony from foreigners, there is a quote from Dhanvantari’s Shakteya Grantha that describes “in clear terms the process of vaccination as practiced by the Hindus“. [9,73]

Above all, however, is the concept of living in harmony with natural rhythms & nature itself. Rather than emphasis on compound chemicals, products of the cow were prized.

Panchagavya is collective name of five products obtained from Cow, which are Milk, Curd, Ghee, Urine and Dung.

#ProtectWithPen pic.twitter.com/iR5yxt3qbg

— Shreeraksha K (@Shreeraksha99) October 31, 2017

Important Texts

Dhanvantari Nighanthu & Chikitsa Tattva Vijnana of Dhanvantari

Chikitsa Sara Tantra of The Ashvins

Sarvasara of Budha

Naadi Vijnana of Kanaada

Jnanarnava of Yama

Dvaidha Nirnaya of Agastya

ChikitsaDarpana & Chikitsa Kaumudi of Kashiraja Divodasa

Vaidya Sandeha Bhanjana of Janaka

Jeevadaana of Chyavana

Tantrasara Sarvadhara of Jabala Kavatha

Nidhana of Paila

Charaka Samhita

Sushruta Samhita

Kashyapa Samhita

Bhela Samhita

Parasara Samhita

Harita Samhita

Ksharapani Samhita

Karaveerya Tantra

Paushkalavata Tantra

Aurabhra Tantra

Aupadhenava Tantra

Vaidyaka Sarvasva of Nakula

Vyaadhisindhu Vimardana of Sahadeva

Gopurarakshita Tantra

Vaitarana Tantra

Videha Tantra

Ashtanga Samgraha of Vrddha Vagbhatta

Ashtanga Hridaya of Laghu Vagbhatta

Andhra Teeka of Ramanujacharya

Ayurveda Rasayana of Hemadri

Raja Nighantu of Narahari Pandit (Kashmir)

Navaneetaka

Raja Martanda of Bhoja

Veerasimhavalokana of Raja Veerasimha (Gwalior)

Rasendra Choodamani of Somadeva (Bhairavapur, Uttar Pradesh)

Kalyanakaraka of Ugradityacharya (Andhra)

Bhava Prakasha of Bhava Mishra (Bihar)

Gunaratnamala

Personalities

Brahma

Ashvins

Dhanvantari

Bharadvaja

Kashiraja Divodasa

Charaka

Sushruta

Maharaja Nimi

Maharaja Janaka

Karaveerya

Drdhabala (Punjab)

Vrddha Jivaka

Nagarjuna

Vrddha Vagbhatta (Sindh)

Madhavakara

Damodara

Govindadas Sen

Acharya Tisata (Kashmir)

Basavaraja (Andhra)

Sodhala (Gujarat)

Vangasena (Bengal)

Conclusion

Neuberger in ‘History of Medicine’ says: ‘In considering of the outstanding independent achievements of the Indians in most branches of science and art, and of their aversion from foreign influences, the trend of opinion today, informed by recent discoveries is in favour of the originality of Indian medicine in its most salient features.’ [7, 176]

In the present era, Ayurveda remains as important as ever. Its long tradition of practical medicine is often minimised to facilitate its appropriation by other societies. Ayurvedacharya Shiv Sharma ji wrote the following in 1929:

Further, this growing interest in Ayurveda has caused a flutter in the dovecotes of the professors of the Western system of medicine who; have started a campaign of belittling, even of positive vilification of Ayurveda, which ignorance and self-interest alone can breed. It is a sinister propaganda and it is time that our cultured countrymen for whom it is primarily meant (for the vast majority of the country still have faith in our old system) should know the value of what they are asked to sacrifice. [9, vi]

That is why it is critical that the tradition of Ayurveda be established as the foundation upon which practical science (vijnana) can be constructed.

To do that, one must not only commence with the foundational texts, i.e.Brihattrayi (Charaka Samhita, Sushruta Samhita, and Ashtranga Hridaya), but also the long lineage of commentaries on these works by respected Ayurvedic physicians. [1, 106]

Commentary

Ayurveda, as with sastra in general, is not static. There is a tradition of bhashyas (commentaries) on medical texts. Yes, the tradition is sacred, but it is built upon in an organic way. Authentic Ayurvedic commentaries in India are found right down to the 20th Century. [7,105]

Clearly one can see the evolution beyond even the earliest treatises such as Charaka and Sushruta Samhita. This is seen not only in the prescription of opiates for pain-alleviation but also in the mention of new diseases. For example, a venereal disease called ‘Phiranga Roga‘ is said to have been introduced through sexual activity with the Portuguese. This is attributed to Bhava Mishra, who wrote in the 16th Century. He published numerous works including Bhava Prakasha and Gunaratnamala. [7, 68] Tambakhu (tobacco) finds its earliest mention in the Yogyaratnakara of Nayanashekar (a Jain priest) .[7,72]

Another interesting aspect is the integral Indic unity of the tradition of Ayurveda. Even as late as the 17th century, Narahari Pandit of Kashmir compiled a Raja Nighantu (King’s medical glossary) listing the names of various medicinal drugs in not only Sanskrit, Prakrit and Apabhramsa (Kashmiri), but also in Marathi, Kannada, and Telugu. [7,100]

Digestion

example of Data Mining by the British in India. Book on Indian medicinal plants 1810. Very rare copy @RajivMessage pic.twitter.com/gWKXfZTi5k

— Inquisitiv_indian (@Inquisitive_Ind) January 5, 2015

Unfortunately, in the context of Ayurveda, ‘digestion’ isn’t always a healthy concept. A neologism coined by the widely read scholar below, it refers to the consumption of the cultural capital of one civilization by another.

Thanks for speaking up against the digestion of ayurveda. This amounts to de-Hinduizing it to be fashionable. BAD! https://t.co/hzxYg671Ut

— Rajiv Malhotra (@RajivMessage) May 17, 2016

As Rajiv Malhotra has been warning, it must be asked, “Is Ayurveda the next Yoga?“

The attempted digestion of Yoga is well-known. Indeed, some alleged “acharyas” of the foreign variety have done their part in strategically helping to claim western influence on Yoga. As such, one can only imagine what lays in store for the multi-billion dollar healthcare bonanza that is Ayurveda. Despite being the venerable calling of vaidyas, the ancient and sacred upaveda, this Vijnana of Dhanvantari may be devoured by Western Science and ultimately cease to be Indian.

The truth is, as Malhotra has written, digestion of Indic Medicine is nothing new. In fact, more than spices, many Europeans are said to have been coming to India in search of medicinal plants. The patenting of turmeric, and other such tradition remedies, is already well known. The question is whether Ayurveda will eventually become simply Aveda…

For this to be avoided, the clash between traditional and modern Hindu, rural and urban Hindu can no longer be permitted to continue (at least to the out-of-hand level it has reached). Ayurveda is our common heritage, and health our common concern. Irresponsible development has lead to health issues around the world, and urban Indians cannot simply “unleash the animal spirits” of a capitalist economy without consideration for rural and tribal citizens. At the same time, traditional Hindus must work with modern Hindus and provide knowledge-based support to ensure our common heritage remains ours. Unless there is a partnership (in place of mutual recriminations), multinational corporations will continue laughing all the way to the bank.

“Ayurveda is practiced on a significant scale today in India, which has fifty eight four-year-degree colleges in ayurveda medicine.“ [2, 115]

Presently there is a degree for Ayurveda (BAMS-Bachelor of Ayurvedic Medicine & Surgery) [7, 189] Can traditional Ayurvedic vaidyas crowd-source funding to preserve their livelihoods from the grubby hands of deracinated digestors? Can doctors trained in allopathy find ways to balance this analytical, mechanical rigour while ensuring the Ayurvedic knowledge system is credited (in papers, etc) when it is utilised for patient care? These are all questions worth asking.

Rather than vaidyas being referred to as ‘witch doctors’ and Indian allopaths being blamed for the profit-driven, pharmaceutical crazy nature of modern medicine, both sets of culturally-aware physicians should find common ground to reinforce each other. As one Indian-origin allopath has written, priority must be patient-care and outcomes. It is true that costs of medical education are outrageous, but these in turn drive up career medical costs. Rather than saddling allopathic doctors with debts at the outset, outcomes can be improved by reducing front-end fixed costs and encouraging community-funded hospitals and health savings accounts rather than private insurance. Private hospitals (with their premium expenses) can continue to exist for those who can afford them, but innovative solutions (best provided by Ayurvedic and Allopathic physicians alike) are the need of the hour. But that will require an integral unity rooted in culture.

Why #allopathy and the cartesian mechanistic view of humans and disease are off track. We need physicians with empathy, as robots can do the pill pushing just fine https://t.co/L2KKp10qH6

— Prof राजीवः श्रीनिवासः (@RajeevSrinivasa) February 9, 2018

There are, in fact, a plethora of cases where traditional Ayurvedic physicians were trained and certified in Allopathy. Dr. Balakrishna Amarji Pathak is one such person from Gujarat. He was a Professor at the Ayurveda Institute at Benaras Hindu University and published Manas Roga Vijnana. [7, 125] Another such person is Dr. A. Lakshmipati from Andhra. He earned an MBBS from Madras Medical College and gained knowledge of Ayurveda from Pandit C.H.Sitaramaiah from Rajamahendravaram. A physician of notable repute in the early 1900s CE, he eventually set up the Andhra Ayurvedic Pharmacy and published works on preventative health as well. [7,129]

There is also a long history of Governmental committee level surveys of Ayurveda. Even the colonial British “Bhor Committee” under Joseph Bhor undertook such a study, with ulterior motives perhaps. Independent India had its preliminary survey under Ramnath Chopra. The Chopra Committee in 1946 recommended an integrated system of medicine including both modern and traditional Indic Medicine. [7, 140] The Indian Government under Nehru decided that such integration was not possible. It went ahead and accepted the recommendation to have an uniform syllabus for Ayurveda in all colleges. There were subsequent committees in 1949 (Dr. C.G.Pandit), 1955 (Dayashankar Dave), 1958 (Dr. K.N. Udupa), and 1963 (Mohanlal Vyas). [1, 141-144]

Today, Benares Hindu University, established in 1916 (under the Colonial BHU Act, 1915) is the largest of the institutions with a dedicated department for Ayurveda (est. 1922). While there were numerous Ayurveda colleges even preceding this, the prominence of this institution reasserted the rightful place of Ayurveda, at least a tad. In 1976, the National Institute of Ayurveda was established at Jaipur. Like BHU, it graduates both BA/MS, MD and PHD students. Another large institution is Gujarat Ayurveda University, and it too has a similarly large scope of degree/certification offerings.

Regarding general organisations, there is the All India Ayurvedic Congress. But like that other All India Congress (Party), it too was founded during the colonial period. Though it began in 1907, it has subsequently conducted more than 55 seminars. [7, 155] In 2000, the National Medicinal Plants board was set up to coordinate matters about medicinal plants.

india is heading in exactly the same direction. terrible quality of health care, very high cost of corporate hospital/#bigpharma allopathy. meanwhile low-cost, personalized, efficacious ayurveda is dying. https://t.co/fDuSRYv7Vt

— Prof राजीवः श्रीनिवासः (@RajeevSrinivasa) January 3, 2018

The Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (est. 2001) has been the bulwark against biopiracy and digestion of Traditional Indic Medicines and pharmocological botany (vriksha-ayurveda). “The Objective of this library is to protect the ancient and traditional knowledge of the country from exploitation through bio-piracy and unethical patents” [7, 156] It was successful in revoking patents of turmeric, neem, and basmati rice by Western governments. TKDL, as of 2010, had transcribed 148 books into 34 million pages of information in five languages (English, German, French, Spanish and Japanese). It is important for these to be further disseminated in native Indian languages, not only on the website, but also through books and national/state syllabi.

Influence

“The doctrine of the humours is taught in unmistakable terms in the holy books of the Hindus, which were composed prior to 2000 B.C. From India the theory seems to have spread to Persia and the Persians, who seem in matters scientific always torch-bearers rather than torch-lighters, carried the doctrine on” [1, xiii]

“as appears from the writings of Hippocrates, Dioscorides and Galen, various drugs and methods of treatment employed by the physicians of Indian were adopted by the practicioners of Greece.” [7, 176]

Contrary to many on the deracinated Left, rather than unani bringing medicine to India, unani itself is a product of ancient Indian medicine.

“Knowledge of the Indian holistic system of medicine, ayurveda, was first integrated with the Iranian unani system of medicine before transmission to Spain and Europe. Hindu physicians Ganga and Manka were invited to treat the well-known khalifa Haroon al-Rashid. A number of Hindu scholars were taken to Baghdad because of the caliph’s interest in getting Sanskrit texts in mathematics, sciences, medicine, and literature translated into Arabic. ” [2, 126-7]

Indeed, as the attempts to digest Ayurveda ascend in number, it becomes incumbent upon all of us to assert the native nature of the tradition. Much as with mathematics and the zero, long credited Indic accomplishments have increasingly been disappearing from previously ‘peer-reviewed’ texts. Perhaps the time has come to reconsider whom we consider to be ‘peers’ and to operate on the basis of the truth we have long known to be…true.

The origin of Indian medicine is not be sought in Greece, Egypt or any other country. The Indians are solely responsible for it. It is not as if medical history traced Indian medical ideas only to a point at which they were already highly developed and could not explain their beginnings. We can trace the history of the Indian humoral theory to its purely Indian beginnings. [1, xlii]

References:

- Kutumbiah, Dr. P. Ancient Indian Medicine. Hyderabad: Orient Longman.1999

- Sardesai, D.R. India: The Definitive History. Westview. Boulder, Colorado 2008

- Achaya, K.T. Indian Food: A Historical Companion. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. 1994

- Madhulika, Dr & Ed. Jayaram Yadav. Paka Darpana. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Orientalia. 2013

- Acharya Balakrishna. Ayurved: Its Principles and Its Philosophies. New Delhi: Diamond Pocket Books. 2006

- Rangarao, Shanti. Good Food from India. Bombay:Jaico.1977

- Yadav, Dr. Deepak “Premchand”. History of Ayurveda. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Subharati Prakashan.2013

- Basham, A.L. The Wonder that was India. Delhi: Rupa & Co. 1999

- Sharma, Krishna (Ayurvedacharya). The System of Ayurveda. Khemraj Shrikrishnadass. Bombay: Shri Venkateshwar Steam Press. 1995

- Varier, N.V.Krishnankutty.History of Ayurveda.Kottakal,Kerala: Arya Vaidya Sala.2016

- Rao, S.K. Ramachandra. Encyclopaedia of Indian Medicine (Volume One): Historical Perspective. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. 2005