One of the most lucid backgrounds yet most occluded histories remains that of the Thathagatha. While orthodox Buddhist accounts and even rival Vedic Dharma’s Puraanas are clear that Siddhartha Gauthama, that is, The Buddha, was of Sooryavamsa Kshathriya background, modernists have attempted to appropriate him for their own purposes.

The Sakyamuni was given his appellation not because he was allegedly a Saka, but because he came from the Sakya (with a Y) clan of the Solar Dynasty. This is the danger of playing etymological games for political purposes. A tradition’s own account can be ignored to ensure a group, an ethnicity, or a narcissistic political cult can utilise and even exploit their own spiritual Guru’s background.

In the immediate aftermath of a Guru’s passing, history and even historiography can be corrupted so that a political faction or outside ethnicity can claim ownership over something attained by the actual possessor (so to speak). That is the danger of materialism, and indeed materiality itself. If this is all there is, then the truth can go for a toss. It is, therefore, only spirituality, which The Buddha himself embodied, that can ensure adherence and accountability to the Truth. That is the importance of our next article in our Continuing Series on Indic Literature: Buddhacharita.

Author

The Author of the Buddhacharita, Ashvaghosha, is almost as well known as his work.

“The Buddhacarita is the celebrated poetical work (Kaavya) attributed to Ashvaghosa, the most outstanding Buddhist poet and philosopher in the Sanskrit literature. He is supposed to have been a contemporary of king Kaniska, the greatest king of the Kushana dynasty” [1, 9]

Said to be highly influential on not only literature, but also the culture and history of Indian society, Ashvaghosa’s impact thereof, needs no debate.

“There is no doubt that Asvaghosa was the author of three works — the Buddhacarita (Bc), the Saundarananda (sau) and Sariputraprakarana. The last colophone of Sau. described Ashvaghosa as Saketa, Suvarnaksiputra, Badanta, Arya and Acarya.” [1,3] Other names attributed to this personage are Maatrcheta, Pitrcheta, Soora and Maatichithra. Other titles included Bhaadhantha, Mahakavi and Mahavaadhin.

Though we know his mother’s name Suvarnakshi, and his place of both as Saaketha (Ayodhya), not much else is known. “According to Chinese tradition, Asvaghosa was a Brahman by birth, but later on, he was converted to Buddhism. ‘In order to benefit the world with noble law of BUddha,’ he was converted to Buddhism and he undertook to write his works. Asvaghosa possessed intimate knowledge of the four vedas, six treatises, vedangas, epics and darsanas“. [1, 7]

“According to Vasubandhu, for his versatility in the literature, he was invited to Kashmir by Katyayaniputra and there he used to compile his great commentary ‘the Vibhasa’.” [1, 7]

As is generally the case with Indian historical datings, there remains much controversy. Per the Western Chronology, however, Ashvaghosa is dated to the 1st Century CE, due to his contemporaneity with Emperor Kanishka.

Composition

A Sanskrit work divided into 2 Books of 14 cantos each, the Buddhacharitha is a splendrous example of Mahakavya. A Hindu genre that dates back to the Ramayana & Mahabharata, it was wielded skillfully by the Buddhists who followed. [1, 10]

“The main features of this work are – 1. Buddha Bhakti and deification of Buddha. 2. Use of miraculous element. 3. The refutation of Brahmanical practices. 4. The conquest of Mara and 5. The gradual development of Mahayana. The [Buddhacarita] was originally composed in twenty eight cantos and was rendered into Chinese and Tibetan…The Sanskrit text of the Poem comprises seventeen cantos only and it is said that one Amrtananda of the ninth century A.D. added these four cantos.” [1, 1]

Notably, cantos 2-13 exist in the Sanskrit recension, with partial existence of cantos 1 and 14. As such, there is significant room for discrepancy. [1, 8] This is unlike his second work, Saundarananda., which has all 18 cantos in existence. It describes the transformation of Buddha’s disciple Ananda into a hermit. The third work, Sariputraprakarana, is a play in 9 acts. However, only a few passages exist based on a manuscript from Turfan in Central Asia. It entails the conversation of Saariputhra with Maudgalyaayana. 2 other fragmentary dramas exist of disputed authorship. [1, 8]

The Buddhacharitha is considered to be a classic and influential Mahakavya. “According to one view the number of Mahakavyas is five. These are Raghuvamsa, Kumarasambhava, Kiratarjuniya, Sisupalavadha and Naisadacarita. ” [1,2] Other oeuvres included in the list of Classical Indic Epic Poetry include Bhattikaavya and Raavanavadha, as well as the Jaanakiharana of Kumaradasa.

“A Mahakavya should be written with Asih (blessing), Namaskriya (Salutation) or Vastunirdesa (reference to the subject matter). ” [1, 3]

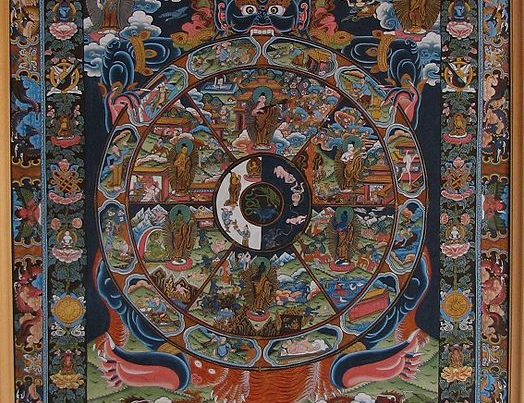

The main sentiment of this poem is Saantha rasa. The peace and tranquility of Enlightenment (Nirvaana) is imbued into the work. There have been a number of revisionist attempts to portray the Buddha as a mere student of Vedanta, happily continuing the “Hindu” tradition of the Sages Araada and Udhraka. However, the Buddhacharitha is clear that although Siddhartha Gauthama showed due respect to these teachers, he was also in disagreement with their doctrines. Hinduism, the core of which is better described as Vedic Dharma, featured the Shaddarsanas, or 6 main perspectives of philosophy. The Buddha evolved his own Dharma.

He, as such, embarked upon the task of originating his own experiential learning. “Arada described a prevalent form of Samkhyayoga teaching in different ways. But, the prince was not satisfied by the doctrines of the sage Arada. He therefore, went to the sage Udraka to hear the doctrines. When, Udraka was also unable to satisfy him..He sat down at the root of a pipal tree and meditated there in order to attain enlightenment. The gods became very glad.” [1, 17] These facts are all recounted in Canto XII of the Buddhacharitha.

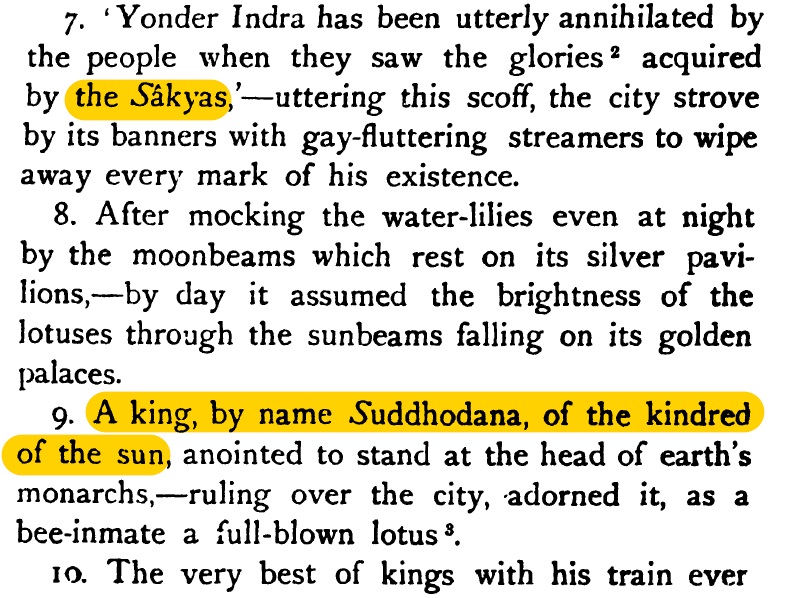

Important individuals in the life of the Buddha are described, starting with his father Suddhodhana and mother Mahamaya, as well as his wife Yashodhara, and son Rahula. Others include the famous merchant Anaathapinda and Kings Prasenajeeth of Kosala and Ajaathasathru of Magadha. Finally, it ends with his attainment of Mahaparininirvaana and his final instructions to his disciples. [1, 22]

It is also clear from the Buddhacharitha that the Buddha was not an ethnic Saaka (Scythian), but ethnic Aarya (Vedic Indian Ethnicity) of the Kshathriya class. He was born under the Pusya Nakshathra per Ashvaghosha. “We get the references of Rajasastra, Nitisastra and Dandaniti in [Buddhacharitha]. From these, we knew the poet’s knowledge of Arthasastra and Rajasastra or books on politics. ” [1, 121]

Poetics

The Buddhacharitha is said to be in Vaidharbhi Reethi, that is, the Style of Vidharbha. It is said to be a concise and elegant style, free of long compounds which characterise the cumbersome and gaudy Gaudi (of the present time). Others include Paanchaali (said to be a blend of the former two) as well as Laatika, which hails from the Laata desa. [1, 33] The metres he uses are Upajaathi and Anushtup, among many others.

There are references to both the Hindu epics throughout the Buddhacharitha. [1, 49] “The poet Ashvaghosa was greatly influenced by the two great epics of India — The Ramayana and the Mahabharata…Ashvaghosa has paid high respect towards the great sage Valmiki, the author of the Ramayana. He acknowledged him as the Adikavi, and has praised him as Dhiman.” [1, 49]

“Though besides Asvaghosa we come across names of some other buddhist poets like Matrcheta, Nagarjuna, Aryasura and Vasuvandhu etc., yet the literary merits of their works are not superior to those of Asvaghosa.” [1, 52] The impact of the Buddhacharitha cannot be minimised. Buddhist Avadhaana literature is directly influenced by this composition. Even Hindu poets such as Rajasekhara make reference to it in their texts. Indeed, selections from the text itself prove this intent as well as the civilizational continuity between the Indic Vedic & Buddhist traditions.

“The main principles of Bauddhadharma is to remove the sufferings of the human beings.” [1, 101]

Selections

1.That Arhat is here saluted, who has no counterpart,—who, as bestowing the supreme hap-piness, surpasses (Brahman) the Creator,—who, as driving away darkness, vanquishes the sun,—and as dispelling all burning heat, surpasses the beautiful moon. (C.1, v.1), [2, 1]

§

2.There the sun, even although he had retired, was unable to scorn the moon-like faces of its women which put the lotuses to shame, and as if from the access of passion, hurried towards the western ocean to enter the (cooling) water. (C.1, v.6), [2,2]

§

3.The very best of kings with his train ever near him, —intent on liberality yet devoid of pride a sovereign, yet with an ever equal eye thrown on all, —of gentle nature and yet with wide-reaching majesty. (C.1, v.10), [2, 3]

§

4.Having dispersed his enemies by his pre-eminent majesty as the sun disperses the gloom of an eclipse, he illuminated his people on every side, showing them the paths which they were to follow.

Duty, wealth, and pleasure under his guidance assumed mutually each other’s object, but not the outward dress; yet as if they still vied together they shone all the brighter in the glorious career of their triumphant success.” (C.1,v.12-13), [2,3]

§

5. Assuming the form of a huge elephant white like Himalaya, armed with six tusks, with his face perfumed with flowing ichor, he entered the womb of the queen of king Suddhodana, to destroy the evils of the world.” (C.1,v.20), [2, 4]

§

References:

- Sarma, Nripendra Nath. Ashvaghosa’s Buddhacarita: A Study.Kolkata: Punthi Pustak.2003

- Cowell, Edward B. The Buddha-Karita or Life of Buddha. Cosmo: New Delhi. 1894, 1977