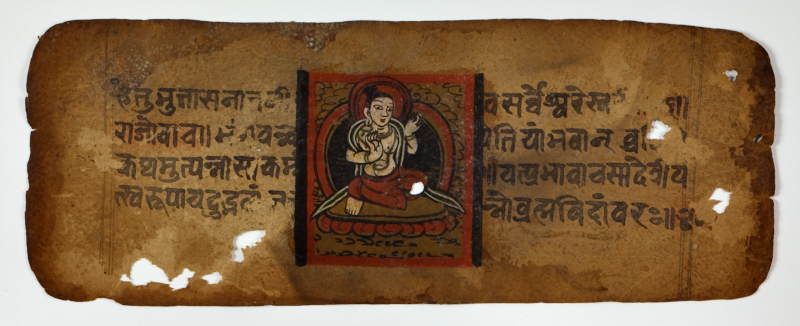

Tradition often finds itself adapting to Modern Times. Following our article on the Literary Nepali Tradition, which covered Pre-modern Literature, our next article covers Modernity.

Modern Literature

Modernos, or modernity, can mean many things to many people. Indeed, the contemporary period is in fact the Post-Modern period. Nevertheless, the roots of it lay in the Early Modern literary era, which exposed Colonial India, and its independent neighbour Nepal, to global western Literature. The effects of this are felt to this day with the widespread Marxist movement in the Kiraatha country.

Interphase

“A new age in Nepali literature begins with Lekhnaath Paudyal (1884-1965), Lakshmeeprasaad Devkotaa (1909-1959) and Baalkrishna Sam (1902-1981), who have left their impress on different genres: Lekhnaath and Devkotaa on poetry, Baalkrishna on drama. Lekhnaath marks the end of an era and the beginning of another. Educated at the Sanskrit school at Kathmandu and later at Benares, Lekhnaath hardly came under the influence of western literature. Influenced by the works of Bhaanubhakta and Motiraam he started composing verses early in life.” [1, 82]

Lekhnath drew the bulk of his inspiration from Sanskrit literature, but what is notable is that he does not merely parrot the old. He seeks to draw from the fount of the civilization while adapting it to the local/regional needs of the Nepali people. “He followed the norms laid down in Sanskrit prosody, but gave a new diction and direction to Nepali poetry. His first significant work Varshaavichaar (Thoughts on the Rains) was published in Maadhavee in 1909. In the description of the rainy season the poet uses metaphors and similes to depict a picture of the society, to reinterpret Hindu culture, to express a spiritual awakening and an ethical concern.” [1, 82-83]

What is also telling is that he wrote poems on Maharana Pratap and the French Revolution respectively. Due to the political tumult of the time, he was forced to destroy them as authors were being closely watched and censored. He would also write Pinjaraako Sugaa (The Parrot in a Cage), written in 1914. However, livelihood demanded that he eventually seek favour at court. He would later write Sokpravaah (Streams of Dirges, 1913) and Gitanjali (1929). Other works included Bhartriharinirved, Panchatantra, and Abhijnaana Saakuntal (1958). The impact of the Classical Indic Canon was apparent upon him.[1, 85]

His most unique work, however, was Satya-Kalisamvad. “Written in 1929 in praise of ancient Aryan culture, Satya-Kalisamvaad (Dialogues Between Satya and Kali Ages) is a poetic critique of the decadence of Hindu society. In it the poet shows his awareness about the cultural rejuvenation of India and also an eagerness to grasp the significant modern developments. The content of the work is revealed in a conversation between two epochs, namely, Satya and Kali. He sees in the internal squabbles and jealousies among Hindus the principal cause of their decline and traces the process of this decadence from the end of Dvaapar age when Kauravas started the internecine war. His subtle barbs on the rigidity of casteism and untouch-ability, a general devaluation of morality, the degradation of women in Hindu society amply show his concern for a Hindu cultural renaissance.” [1, 86]

He was not the only notable author of this period. The second in ‘The Great Trio’ was Balkrishna Sam. He wrote the poetic play Mutuko Vyathaa (Heart Ache) in 1929. He, unlike Lekhnath, was known for being influenced by foreign literature. He wrote in Shakespearean blank verse in tandem with Vedic metres. He was the grandson of Dambar Samser Jung Bahadur Rana, credited with the Royal Imperial Opera House. He was considered a rationalist, and took modernist interpretations to classical Indic stories such as Dhruva and Prahlad (which he composed as plays). “His Bhakta Bhaanubhakta on Bhaanubhakta’s life and Amarsimha about the hero who fought bravely against the British in the Anglo-Nepal War, 1814-16, are but structuralist interpretations of the biographies of Bhaanubhakta by Motiraam and of Amar-simha Thaapaa by Sooryavikram Jnavaalee.” [1, 100]

The third and youngest of The Trio was Devkota. He wrote Sakuntal in 1945, and composed it in 1754 stanzas, and twenty different Sanskrit metres. He then wrote a kavya on Maharana Pratap, inspired by his patriotic ideals. He also wrote Sulochana (a social commentary) and Bankusum (Wildflower), which was a drama on royal succession. Other works include Ravan-Jatayu Yuddha (1946), and Pramithas (Prometheus). This prolific dramatist weaved through Western and Indic stories alike. His later era featured the plays Savitri-Satyavan and Rajput Ramani as well as several essays. If “Lekhanaath’s language is sedate, calm and pure, Devkota’s is spontaneous, even Dionysiac, which holds us under spell. If Baalkrishna’s well-chiselled words sparkle like clean water in the marble pool of a palace, Devkota’s gushes like a hill torrent with glint, froth and foam” [1, 97]

New Sensibility

A palpable shift can be seen in the poetry of people like Dharnidhar Koirala. They made contact with many Indian luminaries, and became desirous of social upliftment. His early poems include Naivedya (Offering) and Guhaar, Guhaar (Help, Help). [1, 107]. Other worthies include Mahananda Sapkota, Parasmani Pradhan, Yuddhaprasad Misra, B.P.Koirala, and Madhavprasad Ghimire. They experimented with new styles and themes, and blended them with the old metres and forms.

Another notable was Gopalprasad Rimal. He was a political rebel against the Ranas and a social rebel against the norms of the time. He wrote Masan (1945) bearing the influence of Henrik Ibsen’s Dolls’s House.

“The theme of Yo Prem (This Love) also veers round the issue of a woman’s rebellion for human dignity. Women are not simply objects of carnal gratification.” [1, 186]

Novel

The modern novel came late to Nepal. “The dearth of novels in Nepali inspired Sadaasiva Sarmaa to bring out a monthly Upanyaas Tarangini from Benares in 1902 with the sole purpose of serialising novels. It serialised Sarma’s own Mahendraprabhaa that year…Sadasiva lived in Benares and was in close contact with Devkeenandan Khatree, the popular Hindi writer of detective novels, and his printing press. As a matter of fact, Khatree’s Chandrakaanta (Part One) and Narendramohini were translated by Sadaasiva into Nepali and were printed in Khatree’s press during 1899-1901.” [1, 167]

The influence of Devkinandan Khatri was apparent elsewhere. Compositions such as Jadugar (The Magician, 1907) and Vichitra Jasusi (Strange Espionage, 1914) are emblematic of this. Pratimansingh Lama’s Mahakal Jasus can also be seen in the same vein. There is some discussion about whether Kadambari of Harshavardhana can be considered a novel (literal in this case); “but it is admitted now that the first fully fledged novel, by modern standards, was Lady Murasaki’s Tale of Genji (c. 1000 A.D.) in Japanese.” [1, 168]

The Nepalese would turn to the novel with great alacrity, on both sides of the Himalayan border. “The first realistic novel in Nepali, Muluk Baahira (Outside the Country) was also published…in 1948. Its writer Lain Singh Bangdel is renowned as an artist. Born at Tuckvar tea garden in Darjeeling in 1924, Bangdel matriculated from the Darjeeling Government High School. As he showed the genius of a painter from his early days he went to Calcutta for study-ing art…Later he settled in Nepal” and became Chancellor of the Royal Nepal Academy. [1, 172]

Sarma and Girisvallabh Josi would take inspiration from global literature as well, writing works of fiction in the genre of horror and political intrigue, along with adventure. The latter, in particular, would satirise the court of the Ranas, in his Viracharitra. [1, 167]

“Different in theme Yampanchak Prapancha, a novelette serialised in Gorkhapatra in 1907, was written by Dvaarikaanaath Upaadhyaay. It contained a reformist message against the evil of gambling. Also social in theme was Venaath Aachaarya’s Dayaakee Bhaavee (The Fate of Daya, 1922)…the period between the First and Second World Wars was the period of great reawakening among the Nepalis of the sub-continent. It witnessed the establishment of the Arya Samaj in Nepal“. [1, 168]

This change symbolised a breach between the old established order and the new reformist one raring to roar ahead. It also heralded a tradition of literary criticism.

Biographical & Historical

Biographical and Historical works provide insight into the political trends of society. Royals tend to very closely guard dynastic narratives, rendering the study of history coloured by familial pride. The continued claim of many modern dynasties of descent from Bhagvaan Raama is emblematic of this, as the lineage actually ended thousands of years ago. Royals too have a responsibility to preserve the truth. In such a climate, historians such as Baburam Acharya and Nayaraj Panta penned their works. The former was granted the title ‘Itihaas Siromani’, and is considered the ‘doyen among Nepali historians’.[ 1, 197]

“The fall of the Ranas gave freedom to the scholars of Nepal and a burgeoning national feeling there as bound to give a boost to historical studies. Baaburaam Aachaarya’s Nepaalko Samkshipta Vrittaanta (1965) was followed by his major work which is a biography of Prithveenaaraayana Saaha in four volumes. Ambika Prasaad Upadhyaay’s history of Nepal (1936) published from Allahabad [Prayaagraaj] was the only work of its kind during the Rana Regime. Baalchandra Sarmaa and Dhundhiraaj Bhandaaree came out with their works on the history of Nepal in 1951 and 1958 respectively. The researches of Yogee Naraharinaath and a great Sanskrit scholar Nayaraaj Panta, who founded Itihaas Samsodhan Mandal, have thrown welcome light on many aspects of the past of Nepal.” [1, 216]

This was a period of tremendous churn and output in Nepal’s history. Indeed, the subsequent tumult and events of the 1990s and early 2000s would be, in large part, due to the prior dissemination of new ideas and revisionist histories. Nepal was certainly independent during India’s colonial period, but it was not untouched by new ideas, and in many ways, its dharmic nationality remains more vulnerable to challenges to its identity.

“Janaklaal Sarmaa’s most important work Josmani Santa Paramparaa Ra Saahitya (1963) is on the saints of an indigenous cult called Jos-mani. Its most important prophet of later times Jnaandil, was also a poet. His reformative zeal has been succinctly summed up by Mahaananda Saapkotaa in one of his articles. A military officer who later turned to be a saint of this cult, Ranaveer Simha Thaapaa, is the subject of a biography written by Samser Bahaadur Thaapa. It was published in 1966.” [1, 217]

Selections

Lekhnath wrote Rituvichaar in Anushtup chhandas, and honored Kalidasa’s Ritusamhaara.

“Nageechako rukho daado hum pardaa Himaalako

Dekhinchha fetaa baadheko moorti jhaee ugra Kaalako

Daahraa tulya chuche dhungaa danda jhaee dhupikaa rukha

Baayekaa paharaa-roopa chautafee gahiro mukha

Near stands a naked hill, when snowfalls on the Himaal.

It looks like a turbaned statue of terrific Kaal.

Sharpened tooth-like pointed rock, the pine stands like a pole;

Wide open is the cliff and on four sides a deeper hole !” [1, 83]

Elsewhere he writes with a more philosophical view:

“Samsaara yo hilo saaraa, padma Isvara-bhakti ho

Jeeva chhan bhyaagutaa tulya padmako rasa mukti ho.”

Mud is this world, lotus devotion,

Beings are but toads, the lotus juice redemption.” [1, 83]

§

Balkrishna Sam had a peculiar style of poetic diction. It was almost dialectical in nature.

“Aagaako bharbharaudo ek suntalaa bhoogolmaa

Bataariera lapkiraheko jwaalaa-jwaalaako samooha—

Ahamkaarle andha bhaikana bhunbhunaeko garjan—

Aafuskaa kaanekhusi; kichaai; nyaanaa aalingan—

Ekchhatree aadhipatya aatmatriptiko kampan

Vyaapta bhaekaa thie sabaitira,

Tara unkai antarbaata

Dalit soshit bhai sesh raheko

Umleko taato paaniko baaf

Abhipanne dalsamgha

Kraantile kaalo nilo pyaaji bhai

Ates-mates gardai nissaasindaee umki maathi maathi utryo

In the orange geography of live fire

Entwined and lapping horde of flames —

Blinded by ego, the rumbling roar —

Mutual whispers, attraction, warm embrace—

Tremors of sole domination of self-satiation

Spread everywhere,

But from the very core of these

The remnant of the trampled and sucked

The vapour of water boiled —

The fugitive water mass

Blackened, blued and crimsoned by revolution

Feeling stuffy, gasping escaped and landed up above.”

[1, 103-104]

§

Devkota believed that ‘A true poet is the garden of Spring’. His poetry reflected that.

“Satyake pahile yasaree paghlyo

rang pagal?

Srishtipareekaa chuhe parelaa

yasaree khajhalkee

Pahile lagaaee yo gaaja?

Did Truth melt thus before

colour-mad?

Did the Creator-Angle’s eyelash droop

glancing this

Her eyes mascara’d?” [1, 93]

Though he was optimistic about the future of man, he was sternly against what he deemed to be the tyranny of the times.

“Bholi huncha dhata gagan pavan nirmal saanta

Ritu basanta haaschha madhur sisir hunchha anta

The sky will be bright tomorrow, the air clean, sedate

Spring will be all smiles, winter’ll abdicate.” [1, 93]

§

Conclusion

“The introduction of western system of education in Nepal and the study of the English language gave birth to a new out-look in the younger generation. Thousands of ordinary, compar-atively uneducated and even illiterate youths of Nepal came into contact with the outside world and say the great difference between their own and the outside world. Records of the Nepal Foreign Office as well as British sources show that in addition to the number of early recruits, a total of 200,000 of Nepal’s best men were recruited by the British during the World War of 1914-1918. ” [1, 75]

“‘Pragatibaadee’ or progressive. There can be different approaches to literature and a sociological approach based on Marxist theory is undoubtedly one of them. But literary works in Nepali have not been examined with scientific rigour by any Marxist; unfortunately much of the works of progressives lacks an objectivity and is polemical in nature.” [1. 210]

Literature can serve to unite but also unwind a nation. That is why it has been historically so closely guarded. Free thought is important, but only truly possible among a high character populace. Those without any sense of civic responsibility, national harmony, or righteousness will seek to harm others to advance themselves. What is the point of being [allegedly] high iq if you routinely produce unashamed traitors like Alcibiades? Modern trends brought many things to the subcontinent, including Parliamentary Democracy. Given the continual decline in the quality of medieval Indic elites, this was not all bad.

However, the flipside to this advancement has also been the rise of naxalism in Nepal and India, which has had an harmful impact on both nations. Can the peasantry (now working class) be treated well without mass militant movements? That is the question these societies must answer. India has somewhat managed to do so through land-reform, modern infrastructure, and public distribution systems. Nepal underwent a Marxist Revolution that overthrew the Monarchy.

The return of Raajadharma (real Raajadharma, not mere code for kasteist kautilyanism…) may provide the basis for proper governance in Bhaarat Ganaraajya and Nepal Ganaraajya alike. Until then, the literature of both nations as well as the common Indic Civilization must exhort the return of a civic dharma in the minds of the people. Never-ending demands by the populace and never-ending corruption by the elites (both bureaucracy-based and caste-based) have only served to take polities and peoples from one disaster to another.

Maturity in the minds of middle-class adults is the need of the hour. The starting point for that is a modern, and indeed, post-modern literature that can elevate the thinking of the masses and elites alike. Uddaret atmane atmanaam. One should elevate one’s self…

References:

- Pradhan, Kumar. A History of Nepali Literature. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. 2020

- Krishnamachariar, M. History of Classical Sanskrit Literature.Delhi: MLBD. 2016

Editor's Note: All emphasis ours in quoted paragraphs.