Introduction

“A Jaataka is a story about a birth, and this collection of tales is about the repeated births—and deaths—of the Bodhisatta, the being destined to become the present Buddha in his final life. Written in Paali, the language of the Theravaada Buddhist canon, the tales comprise one of the largest and oldest collections of stories in the world.” [1, 1]

Currently dated to the 5th century BCE, The Jatakas (Jaathakas) are postulated to have attained their present form around the 3rd century CE. They are derived from a primarily oral tradition, and thus, were put down in written form at a later date.

“The 547 stories all evolve from one vow: the determination made by the Bodhisatta, at the feet of the last Buddha, Deepankara, to postpone his own enlightenment and freedom from the endless round of existences until he is ready to become a Buddha himself and teach others. This undertaking, recorded in the Jaatakanidaana, a lengthy introduction to the Jaataka stories that is regarded as a separate work, sets him apart from other beings.” [1, 1]

Nevertheless, it must be asserted that the source material also draws from other founts. The famous story from The Ramayana involving the noble Shravan Kumar features in the Jataka of Golden Saama. Connections between the Jataka tales and that famous composition the Panchatantra are also difficult to ignore. Modern indologists have erroneously attempted to antedate the Buddha and the Ramayana, but Siddhartha Gautama himself claimed descent from Lakshmana, making this impossible (Ashoka and Yuddhisthira, another such recent chronological reversal, is similarly violative of Classical Indic Tradition).

The impact of the Jatakas cannot be minimised. From Aesop’s Fables to the Arabian Nights and beyond, themes, motifs and outright stories are often recognisable. To understand why, one must turn to the author himself.

Author

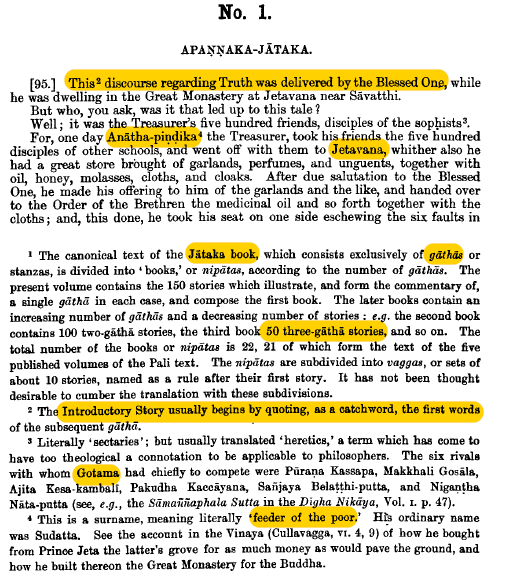

Authorship of the Jatakas is a concept difficult to ascribe. Primarily drawn from the Sutta Pitaka, they are formatted in a matter that attributes their origin directly to The Buddha. Each story commences with disciples surrounding the Thathagatha in a locale (i.e. Jethavana grove), listening to him recount his previous lives.

“A number of epithets are used exclusively for the Fully Awakened Buddha, who describes, interprets and explains the worlds his memory have conjured up for us: the Thus-gone (Thathagatha), the Exalted One (Bhagava) or the Teacher (Sattha). His earlier ‘self’ has two titles: the Great Being (Mahasatta), a bit like the English expression ‘our hero’, or the Bodhisatta, a name which could be taken to mean ‘the one bound for enlightenment or ‘the one attached to enlightenment’. The Buddha, whose name means ‘awake’, is enlightened.” [1, xxvi]

Like the Hitopadesa, it is considered an embodiment of nidharsana-katha, or exemplum. “According to the Buddhist understanding of the mind, formulated in a series of teachings known as the abhidhamma, mindfulness, or alertness, is always present at the moment of appropriate generosity or the wholehearted keeping of the precepts.” [1, xxxvii]

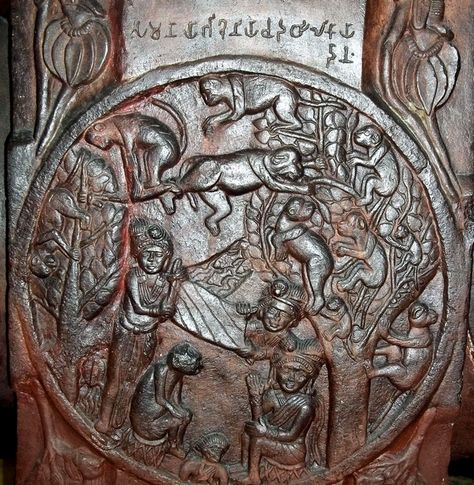

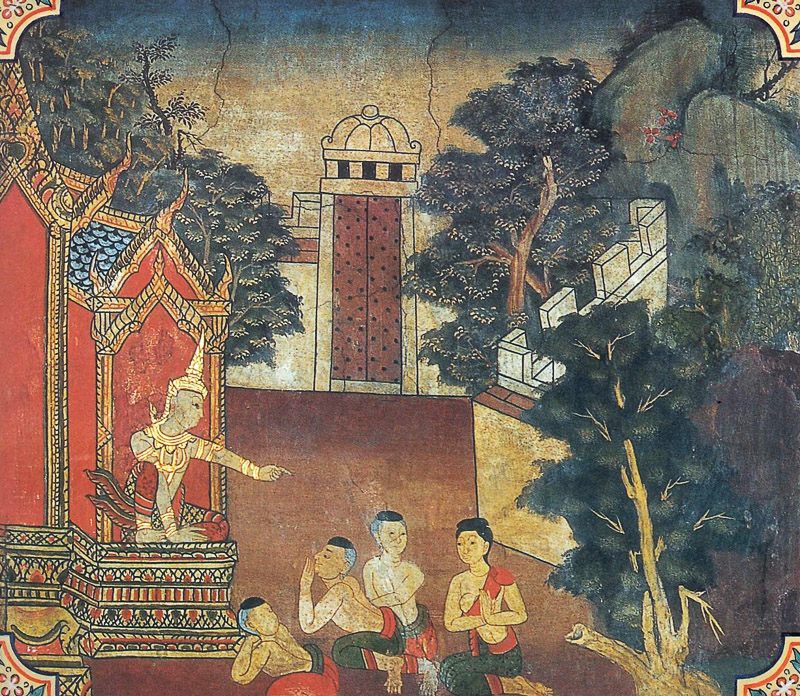

From Bharhut to Borobdur and back, the Jataka tales have inspired people in temples and stupas throughout Asia. The composition, itself, however, has had impact the world over.

“Through his vow the Bodhisatta is able to experience many different types of rebirths…According to later commentarial traditions, that soon become incorporated into the Jaathakas themselves, he fulfils in these lifetimes all ten perfections (paaramee) of generosity (daana), virtue or restraint (seela), renunciation (nekkhamma), wisdom (pannaa), effort (viriya), forbearance (khanti), truthfulness (sacca), resolve (adhitthaana), loving kindness (mettha) and equanimity (upekkhaa). These qualities enable him not only to find a path to enlightenment but to teach others too.” [1, xx]

Composition

Sanskrit (Samskrtham) is the language of the Devas and Dvijas (the three upper varnas). This elite language was not taught to all because of the liturgical ramifications. In the Kali Yuga, as varnas became mixed, there were many lower castes who often demonstrated high character or rose to high positions (such as the Reddi kings) and they became learned in the language as well.

The common language of the people was Prakrit (Praakrtham), of which Pali is a form. As such, the Jatakas are works in Paali precisely so that they would be intelligible to the masses. They serve to inspire them to metta (loving kindness) and high moral character/virtue (sheela). Thus, the Saakyamuni’s own life serves to elevate masses to morality and good behaviour as the path to Nirvaana.

The Composition is divided into 22 nipaathas or books. The form today was translated from Sinhalese to Paali by Buddhaghosa, who compiled it as such from the original gaathas.

“But in the middle of this diversity, the themes of not self (anatta) and impermanence (anicca) are unobtrusively knitted into the very structure of the collection as a whole. Though the Bodhisatta features in all the tales, either as watcher or protagonist, his identity, like that of the other characters, is constantly dissolved at the end of each lifetime with his death…Jaatakas embody Buddhism applied through events: at the beginning of each story the Bodhisatta is again reborn, searching once more for the qualities that distinguish him from other beings.” [1, xxiii]

The Jatakas, however, were not static.

“The texts as we have it evolved over many centuries and association of Jaatakas with particular perfections is probably a later, if deeply creative, development within the tales and popular tradition. It provides a formulation of the work the Bodhisatta sees ahead of him and so a unified way of exploring in greater detail the implications of his vow. A single perfection is cited by name in some stories; ‘The story of the one who taught forbearance’ (313) shows the Bodhisatta’s patient endurance in the face of terrible attack and ‘The story of the hare’ (316) is clearly associated with generosity. ” [1, xxxi]

In the end, despite the humanity and relatability of the Thathagatha, he stands apart from normal flawed men and women in the Jaathaka.

“A Buddha, able to teach gods and men, is said to know all worlds (lokaavidu). Many such worlds are described in the stories.” [1, xxvii]

Selections:

Recounting entire stories over the course of a small article would prove difficult. As such, we have provided relevant selections so as to showcase the wisdom in the Jataka tales.

Each Jataka commences with a Pacchupannavatthu, or Story of the present. It typically describes the contemporary context of the Buddha and his disciples. This is in contrast to the atheethavatthu, or the story of the past (the bulk of the jataka). [1, xxiv]

“This is the heart of each story too: the place of the Buddha, the knower of all worlds, freed at last from any grasping after false ego, or ‘I’—making (ahamkaara), at all.” [1, lxi]

§

§

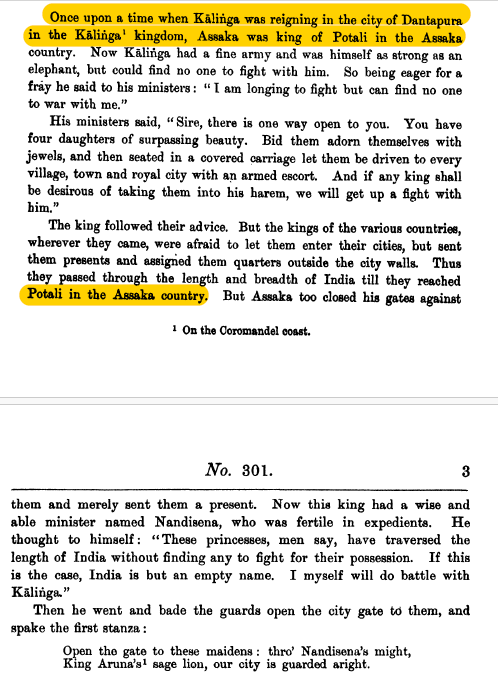

Dhanthapura mentioned as capital of Kalinga. Assaka mentioned on the other end of India.

§

Description of Vesali, capital of the 7707 knights-raaja and the Licchavi relatives of Siddhartha Gauthama.

§

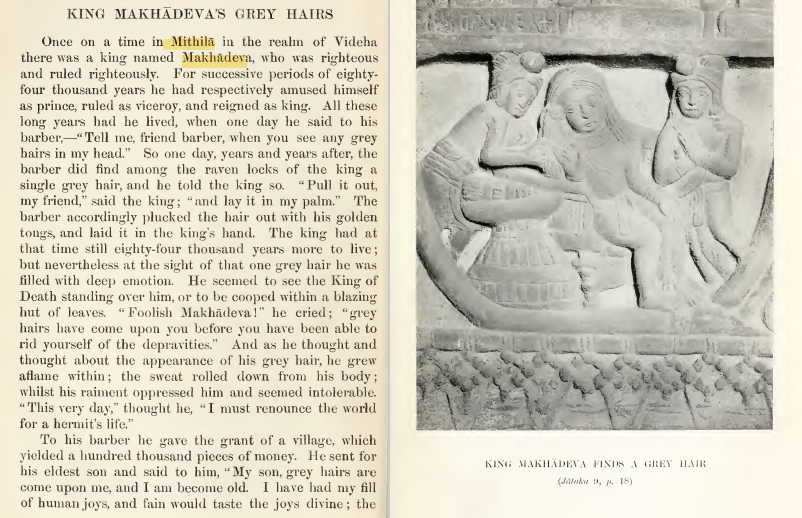

Story of King Makhadeva of Vidheha, who quits worldly life on account of his grey hairs.

§

Perhaps most notable is the inclusion of the story of Raama & Seetha in the Jataka itself.

§

Click Here to Buy this Book!!!

References:

- Shaw, Sarah. The Jatakas. London: Penguin Classics. 2006

- Francis, H.T. & E.J. Thomas. Cambridge University Press. 1916

- Cowell, E.B. The Jataka. Vol I. London: Luzac & Co. 1957

- The Jataka Tales. www.thejatakatales.com