Having discussed two other Dharma sampradayas, namely Sikhi and Jaina, ICP now overviews the third of the Four Distinct Dharma Traditions of Bharatavarsha. At once peaceful and controversial, universal and local, it was the first Dharma to truly transcend class and even nation. Some have argued, that it even presented a truly Global System of Governance that was both moral and political. It is a sampradaya that is best defined by the title of its founder, the Enlightened One.

Indic Civilizational Portal’s Category of Dharma article Continues with this first Post in a new Series on Bauddha Dharma—better known today as Buddhism.

Introduction

“The word Buddha comes from the root Budh, to be awake, to be conscious of, to know. From the same root comes the word Buddhi found in the Bhagavad Gita and meaning in different contexts: intelligence, reason, vision, wisdom. It is the faculty of man that helps him distinguish what is good and beautiful from what is evil and ugly, what is true from what is false, and thus helps him to walk on the path” [7, 9-10]

In an era where ‘religion’ has become associated with many things, it becomes necessary to question the label of ‘religion’ itself. The notion of “one book, one way, etc” is of recent prominence in the subcontinent. Even the Vedic corpus (divided into several books only since the time of Vyaasa) had numerous commentaries on it providing different views and 6 darsanas (Yoga, Samkhya, Nyaaya, Vaisesika, Uttara Mimamsa, & Purva Mimsamsa).

But the Buddha rejected the Veda and still managed to lay the foundation for a multi-variegated understanding of Dharma that transcended a single text. There were numerous texts and sects that emerged from his teachings, and a veritable galaxy of philosophy and terminology. And yet, it was was “Dhamma”, which is the Pali rendition of the Sanskrit “Dharma” that Siddhartha Gautama propounded, not some ‘ism’ classified as ‘religion’.

The Sampradaya of the Buddha is better termed as Bauddha Dharma simply because Dharma does not mean the same as religion. The equivalent word for religion is panth. Bauddha Dharma is distinct from Vedic Dharma, but these Dharmas (along with Sikh and Jina Dharma) have more in common with each other than they do with videshi ‘panths’. Therefore, while Buddhism may be the exonym, it is time to start emphasising the endonym…’Bauddha Dharma’. It is then and then only that rather than being misunderstood as antipodal to Vedic Dharma, it will be understood as it was meant to be: a distinct & separate view of Dharma.

To recognise this, one must go back to the lives of the Bodhisattvas, particularly the most important, the Shakyamuni himself.

The Bodhisattvas

There is a matter of some discrepancy at the heart of Bauddha Dharma. The two major sects themselves disagree on the import and foundational nature of the Bodhisattva. While some hold that the canonical Buddha was himself the first and only one, the majority assert that he was merely one of many Bodhisattvas. But before evaluating whether or not this is the case, one must attempt to understand Bodhisattvas to begin with.

“A Bodhisattva, thus, well equipped with wisdom and compassion, well versed in worldly lores, moves in society to remove the clouds of darkness from the hearts of the people. He protects himself from all evils. In doing everything, he acts with mindfulness and full conscious-ness. He speaks slowly and softly. His kind, clear and meaningful words please the ears and give satisfaction to everyone. He never speaks in a confused language. He does not yearn from chattering. He applauds whenever one utters good words. He commends whenever he beholds a virtuous one.

He does not abandon a good friend (Kalyaanamitra) even for the sake of his life and he does not mind sacrificing his life for a noble cause. He works to attain perfections (paaramitaas,) viz. liberality (daana), morality (seela), forbearance (kshaanti), energy (veerya), meditation (dhyaana) and wisdom (prajna). His self-denying acts and wisdom lead him to enlightenment and he becomes a Buddha. “[1, 49]

In the long list of Bodhisattvas are a few prominent ones.

Avalokitesvara

Amitabha

Maitreya

Padmapani

Manushri

Vajrapani

Nevertheless, the very embodiment of the Bodhisattva remains, at least in the present time, the proverbially original one.

“‘Gautama the Buddha…is the voice of Asia, he is the conscience of the world.’ The teachings of the Buddha, having penetrated deep into the veins of Indian Civilization, spread to all parts of Asia—Ceylon, Burma, Java, Sumatra, Borneo, Siam, Laos, Cambodia, Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal, Tibet, Central Asia, China, M[o]ngolia, Indo-China, Korea, and Japan.” [1,1]

Siddhartha Gautama

In the back-and-forth between the theistic and non-theistic views of Buddhism, comes the background of the Buddha’s life. The Book of the Great Decease is said to be the first ‘biography’ on the Buddha, but was written at least 200 years after his passing. Nevertheless, an essential consistency remains in virtually all accounts.

The Buddha who gave a name to a new Dharma was born in the Himalayan town of Lumbini. Although the date 563 BCE is given based on the present paradigm, traditional Pandits assert the Buddha was more ancient, and in fact born in 1887 BCE, and attained Nirvana in 1807 BCE. Regardless, all parties agree Siddhartha was the son of Suddhodana, of the Shakya clan of Suryavanshi Licchavi Kshatriyas. His mother Mahamaya dreamt of an elephant with a lotus, whilst she was pregnant with him, and soon gave birth to prince destined to become either a Chakravarthin or an Acharya. In a sense, the Shakyamuni would become both.

“As a Kshatriya prince, Gautama showed himself to have superior qualities of strength and intelligence.” [2, 53]

Nevertheless, young Prince Siddhartha Gautama would grow up with an education expected for a nobility of the time. Yet his father, concerned about the prophecy, would shield him from all sorrows and provide him all the pleasures fit to distract a young prince. He was even married off early to Yasodhara, who gave birth to a son Rahula. Nevertheless, the prince of Kapilavastu found no peace in the life of an householder. He pondered over various philosophical questions, never yet finding satisfactory answers. Finally, as the legend goes, he traveled in a chariot with his charioteer Channa one day and saw a sick man, an old man, a dead man, and an ascetic man. Troubled by the ephemeral nature of life, he left Kapilavastu, and traveled throughout Northern India, eventually joining with the mendicants known as Sramanas.

However, here too, despite 14 years of study, Siddhartha would find no satisfaction in austerity and extreme tapas. Finally, at the age of 35, under the Peepal tree (called Bodhi tree) in Gaya, he attained Nirvana. [2, 53]

“His new message, conveyed through his ‘First Sermon at Isipattana’ ‘the present-day Sarnath, was embodied in the well known ‘Noble Eightfold Path.” [1, 76]

From this first upanyaasa at Deer Park, The Buddha would go on to accrue thousands upon thousands of followers. Names such as Anathapindika and Amrapali stud the storied life of the Baudhacharya. Even Emperors such as Bimbisara and Ajatashatru came to him for wisdom. Eventually, he divided his disciples into bhikkus/bhikkunis (monks/nuns) and upaasakas (lay disciples).

“At the insistence of his foster mother and aunt, Krsa-Gautami, but most reluctantly, he agreed to admit women as nuns. Together with the monks and nuns, the Buddhist Order or Samgha was established.” [2, 54]

His aunt was not the only family member to adopt his message. Soon he returned to Kapilavastu, and his son Rahula joined the Buddha’s order.

“The Buddha preached his Dharma for 45 years, walking from village to village and from town to town. His activities were mainly confined to the Madhyadesa (Middle Country). For 25 years he lived at Shravasti and for another 20 years in other places.” [1, 76]

Finally, at the age of 80, the Buddha would demonstrate his last act of dhamma. He ate at the house of a lower caste person, who offered him sukara-maddava (alternately considered to be either pork or truffles). Nevertheless, he ate it out of consideration for his disciple, and soon became ill. With that, the once Prince Siddhartha Gautama attained Parinirvana. [2,54]

Acharyas

With the passing of the Buddha came the inevitable competition over leadership of the Sangha. Not only position but the message itself became a matter of controversy. Without nominating a successor, the Shakyamuni left the world. Regarding this matter, he is recorded to have said the following:

“The truths and the rules of Order which I have set forth and laid down for you, let them, af-ter I am gone, be the Teacher for you.”

As a result, The First Buddhist Council was held at Rajagrha, where the Pali Canon was systemised. The Vinaya Pitaka consisted of 227 rules for the monks, the Sutta Pitaka consisted of a collection of 10,000 religious discourses from Tathagatha. The Abhidhamma Pitaka consisted of the Philosophy of Bauddhas and is exegetical in nature. [2, 56]

A Second Buddhist Council was held at Vaishali, 100 years after Parinirvana. [3, 165] This was where the divine nature of the Buddha was asserted, whereas previously, he had been considered another jeeva. Indeed, the first schism between Mahayana and Hinayana was said to have taken place here. [3, 166] This was followed by a Third Buddhist Council presided over by Ashoka Maurya, and a Fourth presided over by the Turushka Kanishka, who ruled at Kashmir. By this time there were 18 sects and numerous Acharyas, including Kanishka’s contemporary Nagarjuna. The Maurya emperor Ashoka was crucial to the spread of Bauddha Dharma, and he sent bearers of its message throughout Asia, not only to Sri Lanka but also to the West, where Amtiyoka the Yavana (modern Afghanistan) adopted the faith in 1472 BCE. The Yavana Milinda of the Milinda-Panha (Questions of Milinda) was another King in Transoxania who was a significant patron of the faith.

Nagarjuna

Though it has become recent currency that he was an Andhra Brahmin, as established by Pandit Kalhana, and as averred by Pandit Chelam, Nagarjuna was in fact a Kshatriya dated to 1294 BCE. His significance cannot be minimised as he methodically propounded the madhyamika school of Bauddha Philosophy.

Vasubandhu

Famous Buddhist Acharya, said to have been a spiritual leader during the Gupta Empire. Authored the Abhidharmakosa (a treatise on ethics and metaphysics). Originally a Srautrika, his elder brother Asanga converted him. [1, 31]

Dignaga

Author of Pramaana-Samuchaaya. A pupil of Asanga. He laid down the foundations for Buddhist epistemology and logic. [1, 33]

Chandragomin

Bodhidharma

Kumarajeeva

Dharmakirti

Angarika Dharmapala

Punnaachaara

Pilgrimage Sites

- Lumbini (Rummindei village, Terai, Nepal)

- Kapilavaastu (Nepal)

- Gaya (Bihar, India)

- Sarnath (near Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh)

- Kushinara (Kasia, UP)

- Sravasti (Gonda District, UP)

- Sanchi

- Amaravati

- Temple of the Tooth (Kandy)

- Anuraadhapura

Principles of Bauddha Dharma

- The 4 Noble Truths are bedrock of Buddhism. They are the Arya satyaani.

- The 8 Fold Path is the path of Dhamma and the way to Nirvana.

- 3 Sided Purification—sheela (virtue), samaadhi (concentration), & prajna (wisdom).

- 4 Immeasurable Thoughts (brahmavitaaras) should be practiced.

- 5 Precepts are essential to Lay Disciples.

- 6 additional precepts are the next stage of moral development.

- Nirvana or “Enlightenment consists in freedom from samsaara”.

- Buddha has taught that he who holds himself dear should watch himself carefully.

- Dhamma is the guide to all Bauddha disciples and all schools. Saccam the Spirit.

- 10 Morals of Dasasheela are essential for Monks.

- Prajna is found where the mind transcends itself.

- Through Sunyata (emptiness), fullness of knowledge is attained.

- Law of Karma is eternal, but is a continuity of experience rather than transmigration.

- Practice of chastity & non-possession aims at removal of craving for sense pleasure.

- Progress in meditation and wisdom is reciprocal & simultaneous. He who has meditation and wisdom is close unto Nirvaana.

- Na tena ariyo hoti, yena paanaani himsati. Ahimsaa sabbapaanam, ariyo’ti pavuccati.

- Pathavyaa eka rajjena, saggassa gamananena vaa. Sobbalokaadhipaccena, sotaapattiphalam varam.

- A chakravartin or sovereign of the world, possessing a large well-equipped army, is responsible to construct a world order based on compassion and non-violence.

- Lord Buddha…advised in the Cakkavattiseehanaadasutta that a king should rule with justice and remove poverty, to eradicate theft and poverty.. In the kutadantasutta he prohibited the killing of animals for sacrificial purposes.

- “A noble person, fully free from sensuality & malice, is called non-returner”

- “Arhat means a worthy being who has conquered the enemy residing in the mind”

- Sangha: “The Buddhist society was to be a classless, casteless society where there was no room for rituals and sacrifices. The emphasis was only on ethical con-duct without the aid of any priests.”

- Lord Buddha says: “As the wise test gold by burning, cut-ting and rubbing it (on a piece of touchstone), so are you to acc[ep]t my words after examining them and not merely out of regard for me.

Principles & Explanation of Bauddha Dharma

If Bauddha Dharma is ostensibly free of caste, it is full of numbers: 4 Noble Truths, 8 Fold Path, 10 Morals of Dasasheela, and so on mark a system of ethics that found its foundation in Vedic Dharma, but evolved into its own worldview that mingled the teaching of the Upanishads with that of the Sramana, while distancing itself from both.

“Gautama Buddha, also called Saakyamuni, himself claimed to have ex-pounded the old path *puraanamaggo) of the perfect Buddhas of former times (pubbakehi sammaasambuddhehi).” [1,2]

1. The 4 Noble Truths are bedrock of Buddhism. They are the Arya satyaani.

The Four Noble Truths are the most memorable of the principles of Bauddha Dharma. The Chatur Arya Satyaani are as follows:

- Truth of Suffering

- Truth of the Origin of Suffering

- Truth of the Cessation of Suffering

- The 8 Fold Path leads to End of Suffering

More broadly, it establishes that existence is suffering, suffering is born from desire and unfulfilled craving leading rebirth, cessation of desire leads to cessation of pain, when desire ceases the cycle of samsaara ends and Nirvaana is attained. [2, 55]

2. The 8 Fold Path or Ashtangika marga is the path of Dhamma and the way to Nirvana.

Eight Fold path is the Path of Dhamma. It is divided as follows:

- Right View (Samyak-drsti)

- Right Thought (Samyak-sankalpa). Freedom from lust, ill-will, untruth, etc

- Right Speech (Samyak-vaacha). Truthfulness, pleasantness, politeness

- Right Action (Samyak-karman). Sexual propriety, non-violence, non-stealing

- Right Means of Livelihood (Samyak-aajeeva). Following a moral/ethical occupation

- Right Effort (Samyak-vyaayaama). Avoidance of ill-will and bad thoughts

- Right Mindfulness (Samyak-smrti). Vigilant attention to body, mind, and spirit

- Right Concentration(Samyak-samaadhi). Practice of 4 stages of meditation [1, 50]

3. The 3 Sided Purification.

The 8 Fold Path is considered an expanded version of the 3 Fold Purification. Nevertheless, these 3 points are central to the essential Buddhist Triratna. Sheela is more correctly translated as character, but this nevertheless demonstrates the central aspect of Dharma, which is character-building.

Seelam samaadhi pannaa ca Vimutti ca anttaraa

Anubuddha imedhammaa Gotamena yasassinaa.

“Moral virtue, concentration, wisdom and incomparable freedom, these verities were realized by the illustrious Gautama (Buddha).” [1, 55]

Morality, and moral discipline is what makes possible concentration and mental purity. This in turn grants wisdom, which paves the way for true freedom. [1, 56]

4. 4 Immeasurable Thoughts (brahmavitaaras)—maitri (friendliness), karuna (compassion), samata (equanimity), mudita (happiness in seeing someone benefit).

These are described as the four sublime states in the Deegha Nikaaya. [1, 59] They are virtues to be developed as much as possible, and seen as the core of the dhamma and part of the spirit of saccham.

5. 5 Precepts are essential to Lay Disciples

There are 5 precepts new initiates to the Sangha must observe

- Abstinence from taking life

- Abstinence from theft

- Abstinence from adultery

- Abstinence from telling lies

- Abstinence from taking intoxicants

6. 6 additional precepts are the next stage of moral development:

- Abstinence from slander

- Abstinence from impolite speech

- Abstinence from talking senselessly

- Abstinence from covetousness

- Abstinence from malevolence

- Abstinence from false views

7. Nirvana or “Enlightenment consists in freedom from samsaara” [1, 65]

Samsaara is the cycle of births and deaths, the variegated realm of miseries and impermanence. One who has attain Nirvana is steeped in the self and free from the dualities of pleasure and pain, attaining the permanent calm of transcendental bliss.

“Nirvaana is the ‘supreme bliss’: Nibbaanam paraamam sukham; it is the ‘immortal’ (amatam) ‘unique’ (anuttaram), ‘imperishable’ (acyuta) ‘abode of peace’ (santivarapada), the ultimate goal of Buddhism and its raison d’etre…The state of Nirvaana is ‘beyond the realm of death’ (maccudheyyassa paaram); it is ‘unspeakable’ (avaacya), ‘beyond discussion’ (anabhilaapya) and ‘beyond discursive reasoning’ (atarkaavacara).” [1, 66]

8. Medium of Mindfulness : “Buddha has taught that he who holds himself dear should watch himself carefully.” [1,60]

“The Buddha says ‘Mindfulness, O monks, I say, is essential in all things, everywhere.’ Mindfulness is a power, a process which trans-forms human personality and leads from ignorance to knowledge. It implies awareness, vigilance, recollection, remembrance and promotes tranquility of mind.” [1, 61]

There are four main types of mindfulness:

- Bodily Mindfulness

- Emotional Mindfulness

- Consciousness Mindfulness

- Mental Mindfulness

“Mindfulness with regard to body means an ardent contemplation of the body and a clear comprehension of it…Mindfulness with regard of feelings and sensations implies aware-ness and understanding of the feeling of pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral…Mindfulness with regard to consciousness means awareness of different kinds of thoughts…Mindfulness with regard to mental objects refers to the mindful awareness of mental objects (dharmas)” [1, 61-62]

Mental objects include the 5 hindrances (neevarnas). These are 1. Sensual desire (kaama chhanda), 2. ill-will (byaapaada), 3. sloth (thina-middha), 4. restlessness (uddhacca-kukkucca) and 5. sceptical doubt (vicikiccha). [1, 61]

9. Dhamma is the guide to all Bauddha disciples and all schools. Saccam the Spirit

“A man is not on the path of righteousness [dhamma] if he settles matters in a violent haste. A wise man calmly considers what is right and what is wrong, and faces different opinions with truth, non-violence, and peace. This man is guarded by truth [saccham] and is a guardian of truth. He is righteous and he is wise.” DP (G.256-257) [7]

Nirvaana is called the great bliss. This is due to its essential harmony with the spirit of truth, practice of which is called Dhamma. “And the words of Dhamma are words of Truth.” [7, 33] This is the spirit of Satya-Prema.

“Love is beauty and beauty is truth, and this is why in the beauty of a flower we can see the truth of the universe. This is how Buddha speaks of love in the Majjhima Nikaya:

Buddha spoke thus once to his disciples: The words of men to you can be of five kinds: at the right time or at the wrong time, true or false, gentle or bitter, profitable or unprofitable, kindly or resentful.

If men speak evil of you, this you must think: ‘Our heart shall not waver; and we will abide in compassion, in lovingkindness, without resentment.” [7, 21]

10. 10 Morals of Dasasheela are essential for Monks

There are ten injunctions that are pivotal, particular for monks:

- Abstinence from taking life

- Abstinence from theft

- Abstinence from sexual intercourse in any form

- Abstinence from telling lies

- Abstinence from taking intoxicating things

- Abstinence from eating at the wrong hour

- Abstinence from enjoying vulgar or sense-stimulating shows

- Abstinence from using unguents and ornaments

- Abstinence from sleeping in luxurious beds

- Abstinence from taking money

11. Prajna is found where the mind transcends itself.

Prajna is typically translated as intelligence, but here it is used as wisdom. Rather than treating the mind as objective, Bauddhas recognise that it has its own effect and colours the object being observed. Therefore, true wisdom is found in transcending the mind and relying on intuition to perceive reality. In the Middle Patha, Sunyata (emptiness) is treated as affiliated with Prajna. [1, 30]

12. Through Sunyata (emptiness), fullness of knowledge is attained

Sunyata is considered essential not only to Madhyamika (the Middle Path) but also to the Buddha’s own original view. “As the Buddha has said in the Udaana, if we are unable to see something as a whole in its unique individuality we would be apt to offer honestly many divergent and discrepant explanation.” [1, 38] Therefore, by emptying ourselves of preconceived notions and biases, full perception is gained.

13. Law of Karma is eternal, but is a continuity of experience rather than transmigration

Although the Buddha borrows the concept of Karma from the Upanishads, there is a distinction. Unlike Hindus and Jainas, Buddhists see life as a stream of experience rather than distinct lives in which soul transmigration occurs. Karma is deemed as autonomous, and functions as a universal law. [2, 55]

14. “The practice of chastity and non-possession aims at the removal of craving for sense gratification”. [1, 43]

The demon Maara famously tempted the Buddha, who is called Maarajit. The Mahasramana’s victory over Maara is the representation of his victory over the senses. Chastity and non-possession reduce the power of the senses and craving for sense gratification (kaama-trshna). This ultimately make possible attainment of Nirvaana.

15. “Progress in meditation and wisdom is reciprocal & simultaneous. He who has meditation and wisdom is close unto Nirvaana.” [1, 57]

Meditation of various sorts is described and 4 stages prescribed. It is deemed as essential to the path of Dhamma. “Nirvaana is neither a ‘thing’ nor a ‘nothing; it is beyond thingness and nothingness.” [1, 67] Therefore, meditation is deemed as essential to understanding it.

The four stages of meditation are as follows:

- Meditation aloof from sensuality (savitarka-savicaara-vivekaja-preetisukha)

- Meditation with Intuition (adhyaatmapramodannit preetisukha)

- Meditation with equanimity (upeksaa-smriti-samprajanya-sukha)

- Meditation with mindfulness (upeksaa-smriti-parisuddhi-adukhaa-asukha vedanaa)

Each stage is divided into 3 orders: initial (paritta), middle (majjima), final (panita). [1, 63]

16. One does not become a noble (Aarya) because one kills living beings. By non-violence towards all living beings one becomes noble.DP (G.270) [1, 46]

This quote comes from the famed Dhammapada. It asserts that a nobility is achieved through perfect non-violence.

17.” The reward of the first step in holiness is better than the sole sovereignty over the earth, better than going to heaven, and better than lordship over all worlds.”[1, 46]

Here it is clear that Nirvaana is distinct from heaven. The Buddha asserts that this position is higher than any earthly one. DP (G.178)

18. “A chakravartin or sovereign of the world, possessing a large well-equipped army, is responsible to construct a world order based on compassion and non-violence.” [1, 42]

It is odd that a sampradaya which stressed ahimsa would aver the use of an army for a Chakravarthin. Yet, Bauddha Dharma was eminently a practical dharma. Indeed, a true Chakravarthin “conquers the world not by force, but by means of dharma (righteousness) only“. [1, 41]

19. “Lord Buddha…advised in the Cakkavattiseehanaadasutta that a king should rule with justice and remove poverty, to eradicate theft and poverty.. In the kutadantasutta he prohibited the killing of animals for sacrificial purposes.” [1, 45]

19. “Lord Buddha…advised in the Cakkavattiseehanaadasutta that a king should rule with justice and remove poverty, to eradicate theft and poverty.. In the kutadantasutta he prohibited the killing of animals for sacrificial purposes.” [1, 45]

Though non-vegetarianism is not unknown among Bauddhas, the Buddha himself advocated vegetarianism as part of non-violence. This becomes all the more trenchant if his last meal was in fact truffles (rather than that the controversially translated pork).

Nevertheless, he mandated that Bauddhas abstain from sacrificial slaughter at a minimum.

20. “A noble person, fully free from sensuality & malice, is called non-returner (anagamin)” [1, 47]

Anaagaamins were those who were still embodied, but would not return for rebirth. They had not yet transcended the craving for the world, and still had pride, but it was deemed that there was no chance of falling back. “A noble person who has got into the stream of peace, step by step, overcomes sensuality, malice, and delusion of mind which prevent discernment of the truth. He reaches a condition of saintliness where worldly lust becomes weak; yet it has power to force him to take one more birth. He is called once-returner (sakrdaagamin).” [1, 46]

21. “Arhat means a worthy being who has conquered the enemy residing in the mind” [1, 47]

Arhats are an essential aspect of Bauddha Dharma. This status is attained through annihilation of the ten fetters:

- Stakaaya-drsti (the idea of self-eternity)

- Sheela-vrata-paraamarsha (idea of efficacy of purification by ritualism or austerity)

- Vicikitsa (doubts about the Triratna, or triple-gems)

- Pratigha (malice)

- Kaamaa-raaga (sensuality)

- Roopa-raaga (lust of heaven, having form)

- Aaroopya-raaga (lust of heaven, having no form)

- Maana (pride)

- Auddhatya (instability of mind)

- Avidyaa (ignorance)

22. Sangha: “The Buddhist society was to be a classless, casteless society where there was no room for rituals and sacrifices. The emphasis was only on ethical con-duct without the aid of any priests.” [2, 56]

The Sangha is open to all castes, genders, and backgrounds. It is an order consisting of monks and layperson, dedicated to ethical conduct through the 8 Fold Path and the teachings of the Buddha.

23. Lord Buddha says: “As the wise test gold by burning, cut-ting and rubbing it (on a piece of touchstone), so are you to acc[ep]t my words after examining them and not merely out of regard for me. [1, 48]

The Buddha did not claim any divine origin for himself. Thus he leaves it to his disciples themselves to test the truth of his teaching. “Buddhism leaves men free to act for the removal of all social evils, from the cultivation of good conduct and for the service of mankind.” [1, 48]

Buddhist Philosophy

The most fundamental concept in Bauddha Dharma is the ultimate objective of Nirvana. It goes by many names in the Pali Canon and other Buddhist literature: Nirodha, Nirmoksa, Nivritti, and Nirveda.

“Nirvana means the annihilation of passion, hatred, and delusion. It is a tran-scendental state from craving suffering and sorrow. Its positive character is inexpressible in any terms of finite experience, for its reality transcends the realms of birth and death.” [2, 56]

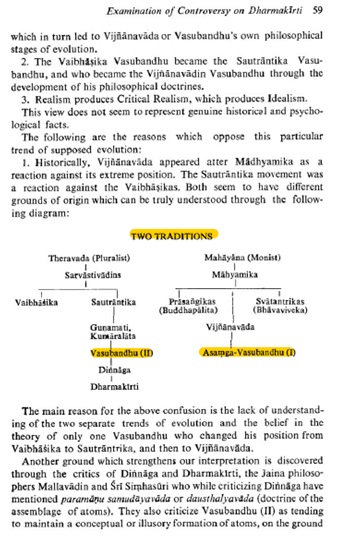

Nevertheless, many understand the same concept differently. There are a number of sects as well as four schools of Philosophy. These are Sautraantika, Vaibhaashika, Madhyamikaa, and Yogachaara. [1, 103] All of them rely on the doctrine of Pratitya-samutpaada (dependent origination). It is linked to the Second and Third Noble Truths. It provides 12 links in the causal wheel of dependent origination

- Ignorance (avidyaa)

- Impressions of Karmic forces (samskaara)

- Consciousness (vijnaana)

- Psychological organism (naama-roopa)

- Six Sense organs, including the mind (shadaayatana)

- Sense object contact (sparsha)

- Sense experience (vedana)

- Thirst for sense enjoyment (trshna)

- Clinging to sense enjoyment (upaadaana)

- Will to be born (bhava)

- Birth or rebirth (jaathi)

- Old age and death (jaraa–marana)

Dhamma is the path to escaping these links, and Nirvana the goal. And yet, there are different views on many of the same concepts. The Vaibhaasikas hold that both knowledge and knowable are real. The Sautranikas hold that knowledge is real, but is known through inference. [6, 98] The Madhyamikas stress the centrality of voidness. The Yogachaaras assert the only real existence to arise from consciousness. Thus, they are also called vijnaanavaadins.

Vijnaanavaada

Vajraayana

This school appeared at Vikramasheela in Bihar. Influenced by Tantrism, it soon made its way to to Tibet and beyond.

Videshi Schools

There are a number of Videshi schools of Buddhism. These have typically combined Bauddha Dharma with local beliefs and philosophies. Examples include Zen Buddhism (a combination of Bauddha and Shinto), and of course most famously, Tibetan Buddhism. The latter in particular is known for its eclectic mix of theories, including a heady dose of Tantra too.

Buddhist Sects

“Both Heenayaana and Mahayaana criticize the Hindu caste system. A Buddhist has no caste and he is free from the social restrictions im-posed by the Hindu Laws of Manu and others. The Buddhist samgha is free from cast[e] distinctions. Buddhism has a place for ev[e]ryone without any distinction of race or colour. This feature of Buddhism was respon-sible for its spread in the countries of Asia in olden days.” [1, 52]

Buddhist Sects are known as Nikaayas. Theravaada is considered the oldest as well as the most orthodox. Mahasanghikas were the first rebel/breakaway sect. [1, 102] Due to politics between the two, the disparaging name of lesser vehicle (Hinayana) was attached to the older one, while the newer one called itself the greater vehicle (Mahayana). Nevertheless, adherents of Hinayana insist on calling themselves Theravada, hence the original names will be used here:

Theravada

“In the Theravaada Buddhism especially, there is no place for any belief in God, or his prophet or his incarnation. Gautama the Buddha was neither an incarnation nor a prophet. He was born and brought up a man and he attained enlightenment by his own efforts. The Buddha’s personal name was Siddhaartha. The Buddhahood is an attainment which has been and can be attained by others also.” [1, 113]

Theravada (Hinayana) is know for its strict adherence to traditional orthodoxy. It emphasises simplicity over ritual grandiosity. The central dogma places focus on the individual achieving Nirvana, rather than adherents relying on the grace and compassion of Bodhisattvas. Theravada favours the use of the original Pali, rather than the more classical Sanskrit. The word Thera in Pali means “Elder”. [2, 58] Theravada is found today mostly in Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia, as well as in Sri Lanka. [2, 59]

Also known as Sthaviravaada, it gave birth to the most number of sub-sects. These were as follows

- Vaatsiputriyaas

- Mahisaasakaas

- Dharmaguptikaas

- Sautraantikaas

- Sarvaastivaadins

- Kasyapiyas

- Sankrantivaadins

- Sammitiyaas

- Shannaagarikaas

- Bhadrayaanikaas

- Dharmottarinyas

Mahasanghikaas

“The Mahayana faith naturally appealed to kings, nobility, scholars, and the elite because they could claim to be bodhisattvas, su-perior to other fellow beings by virtue of the extra merit they had earned through good works toward others.” [2, 59]

Other differences include the use of Sanskrit over the more populist Pali, elaborate rituals, and elevation of Bodhisattvas to the rank of Gods. Perhaps this reason underscores why Buddhism as it is practiced is best viewed as agnostic rather than strictly atheistic. There are deities, even in a popular sect such as Mahayana.

Mahayana produced the following sub-sects

- Ekavyavahaarikas

- Gokulikaas

- Behusrutiyaas

- Caitikas

- Praknaptivaadins

Interestingly enough, Theravadins critiqued that Mahasanghikas began to mimic many aspects of Hinduism:

“As centuries rolled on, the number of individuals, royals, and rich, saintly, and scholarly who claimed to be bodhisatt-vas and a large following of devotees increased. When they died, temples were built for them, and their images were regularly worshiped. Rituals and recitals of the holy scriptures with attendant offerings increased among the followers of the Mahayana faith. The number of temples for the Buddha and his previous incarnations as a bod-hisattva also multiplied. The Mahayana Buddhists looked more and more like the Hindus.” [2, 60]

Many Hindus avow that Buddha should not be included in the Dasavatara, as an incarnation of Vishnu. Nevertheless, this had become popular opinion by the late 20th century.

Buddhist Texts

“it may be pointed out that with the develop-ment of Buddhism as a world-religion, Buddhist literature also rose to the rank of a world-literature. It was studied all over Asia, and many of its legends, fables, and anecdotes found their way into Europe. Nay, it is even sur-mised by many, that the Christian Gospels, and particularly the story of Christ’s life, were profoundly influenced by the Buddhist canon. Rudolf Seydel, who has gone more deeply into this branch of study than any other scholar, has pointed out a close agreement between a larger number of Buddhist and Christian legends, parables and maxims. From this he has derived the very natural conclusion that the Bible is indebted to a large extent to the Buddhist literature.” [3, 183]

The Literary Canon of the Bauddhas is plentiful and transcends time and nation alike. Whether it is in Sri Lanka, Tibet, or modern Europe and North America, many Buddhists have commented on various aspects of the tradition. But if a philosophy becomes mere methodology and ideology, then its coherence is lost. Therefore, the core texts of the Bauddha Tradition should be understood.

The essence is the Tripitika, that is the 3 Pitakas. These in turn consist over additional portions such as the Nikaayas. The Dheegha, Majjhima, and Samyutta Nikaayas are among the most important. The first discusses basic aspects of the Bauddha Creed, the second includes moral lessons in the form of parables, and the third, the suppression of selfishness. There are two others, which contain key works such as the Jatakas, etc.

Pali Canon

- Sutta Pitaka

- Vinaya Pitaka

- Abhidhamma Pitaka

Nikaayas

Jatakas

Theragatha

Vibhaashas (commentaries)

Dhammapada

Buddhacharita by Ashvagosha

Buddhavamsa

Divyavadana

Lalitavistara

Samaadhiraaja

Lankaavataara

Astasaahasrikaa

Prajnapaaramitaa

Gandavyuha

Saddharmapundareeka

Dasabhoomika

Suvarnaprabhaasa

Tathaagataguhya

Vajracchedika

Bodhicharyaavataara & Sikshaasamucchaya by Shantideva

The Sangha

“The Buddhist society was to be a classless, casteless society where there was no room for rituals and sacrifices. The emphasis was only on ethical con-duct without the aid of any priests.” [2, 56]

There is one aspect that is often discussed but rarely explored in multi-disciplinary depth, and that is the role of the Buddhist sangha. While Hindus have had Mathas for millennia and Jainas have ganas, Buddhists have managed to produce centralised Sanghas with great frequency. Arguably, the largest one was in China during the T’ang Dynasty, and functioned as almost a proto-vatican. The net result was a political pushback and a fall in the influence of Buddhism there. The lesson, therefore, is one of decentralisation and accountability for any institution, be it political or religious, in order to prevent the conflation of the two.

The best course would be to look back on the Tathagatha’s own actions and understand the path he laid out:

“The Buddha did not established a ‘Church’ in the Western sense. Instead, he established an association of followers called the samgha, whose membership was open to all, male or female above the age of fifteen, irrespective of any distinction based on caste or class.” [2, 57]

Nevertheless, there were provisos and protocols

- Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha form the Triratna (Three Jewels)

- New converts needed a preceptor to sponsor him/her into the sangha

- Instruction lasted for 16 years after which full voting rights were granted

- Monks were to travel for 8 months, and stay in 1 place for 4 months (vassa)

- Daily recitation of pattimokkhar (treatise on the listing of offences by monks)

- The only exclusions were for the medically contagious or politically imprisoned.

Conclusion

“The Buddha Dhamma is fundamentally altruistic the D[h]amma was proclaimed by the Buddha ‘for the good of the many, for the benefit of the many out of compassion for the world’. The Buddha D[h]amma teaches right relationship between man and man in all spheres of life. The Dhamma is a social necessity, nay even a social responsibility of a cultured society.” [1, 114]

The Influence of Bauddha Dharma is difficult to deny. “To the classic clois-ters of Buddhist learning at Nalanda, Vikramashilaa and Udantpuri the daughter countries of the faith sent their scholars to dive into the depths of the Indian lore and draw on the vast intellectual treasures obtainable there.” [1, 100]

From Central Asia in the West to Japan in the East, Ancient Buddhists traveled and found converts to their faith from many different nationalities and cultures. The very course of civilization itself in Asia was marked by the meditations of the muni of the Shakyas.

Dharma and even the Chakra and Chakravarthin became synonymous with Bauddhas. And yet, rather than breeding harmony, this has bred competition.

There has long been a rather artificial dichotomy between “Buddhism and Brahminism” externally foisted on Indian Civilization. While there were no doubt sampradayic rivalries, even within Vedic Dharma, the use of “isms” rather than the more proper ‘Dharma’ undercuts many elements of philosophical unity between Bauddhas and Vaidikas. The Buddha himself belies this, however searing his critiques of both ritualism and sramanism.

Buddhist account of gohatya

“The Ancient Rsis were ascetics (tapassino) and practiced self-control and avoided the five pleasures of the senses…They spent 48 years of their life as brahmacarins in quiet of knowledge and good conduct. Even after their marriage they lived a life of restraint. They held austerity, rectitude, tenderness, love and forebearance in high esteem. They performed sacrifices with rice, beds, clothes, ghee or oil, which they could collect by begging and never killed cows in sacrifices. They possessed a noble stature and a tender and bright mien and remained always engaged in their own pursuits.

In course of time, however, they began to cove[t] a king’s riches and splendour and objects of pleasure such as women with ornaments, chariots yoked with stately horses…Coveting more and more they again persuaded him (King Okkaku, that is Ikshvaku) to celebrate sacrifices by offering of cows, which they said, constituted also the wealth of men…The slaughter of cows enraged the gods Brahma, Indra and even the Asuras and Rakshasas and multiplied the diseases which were originally three, viz. desires, hunger and decrepitude, to ninety-eight and further caused to appear discord among the people and within the household, and acts improper and impious among the various classes of men.”[5, 291]

Sanctity of the Cow in Ariya Dhamma

It is well known that in the rivalry of “Buddhism and Brahminism” there is another one of Kshatriyas and Brahmanas. Himself claiming descent from Suryavanshi Kshatriyas, the Shakyamuni naturally saw the matter through his own lens. Nevertheless, rather than wholesale condemnation of “Brahminism”, or more correctly Vedic Dharma, the Buddha was more concerned about the downfall of Aryas, and himself proposed his Dhamma as the essence of the original ‘Arya Dharma’. Despite preference for his own, he had respect for the other:

“The true Brahmins are distinguished from the false ones by Buddha and are well spoken of by him. Such Brahmins were expected to observe the five dhammas: truthfulness (saccam), austerity (tapam), continence (brahmacariyam), study (ajjhenam) and gifts (cagam). (sutta-Nipata p.85).” [5, 293]

From Guru Nanak Dev to Vardhamana Mahaveera to Siddhartha Gautama, the Kshatriya progenitors of Kali Yuga Dharmas themselves did not excoriate the Ancient Rishi or the honest traditional brahmana. Rather, their target was corruption & criminality everywhere, especially in the most privileged. Rishis and Rajas alike have fallen from time to time, what to say of Raajaputras and Pandas of the Kali Yuga? Rather than a militating and methodical warfare of the classes, what was sought out by each was a restoration of Truth, whether it went by the Punjabi Sat, the Prakrit and Pali Saccham, or the Sanskrit Satyam.

“In ‘truth‘, the mind is wholly free from all trace of subjectivity and the whole world of individuals, subjects and objects is wholly imaginary. Of the mind and its purity, it is hard to ever distinguish any definite nature.” [1, 30]

“The mendicant in Buddhism is an embodiment of chastity, non-violence and non-possession; hence he is adorable. A mere cast[e]—brahmin is not an object of adoration. The mendicant is a brahmin of the Buddhists and everyone may attain this Brahmanhood by purifying himself. Thus Buddhism opens the door for all people to obtain the true Brahmanic condition. ‘Him I do not call a Brahmin,’ declares Lord Buddha, ‘who is born from the womb of a mother. He may be addressed merely as sir, if he is well-to-do. He who is free from any possession and is not grasping, him I call a Brahmin.” [1, 45]

As such, the views of The Buddha are clear from his own words (rather than those who would put words in his own mouth). Indeed, for all the talk of rivalry, Kalhana records harmony between Buddhists and Hindus in Kashmir. Satavahanas, Guptas, and Harsha Shiladitya were patrons of both despite being primarily Hindus. Thus, rather than being a pulpit for adharmic videshis, Bauddha Dharma should be a path for casteless desis. Desa dharma too is part of Dharma, and rather militating against fellow nationalists, Bauddha Dharma offers a chance for immediate dignity among the downtrodden. It is not for nothing that the chairman of the drafting committee of the Indian constitution chose Bauddha Dharma to complement his patriotism.

Indeed, it is no mere coincidence the modern Republic of India, which adopted a Buddhist Emperor’s Lion Capital as its emblem, also adopted an Upanishadic phrase as its motto.

Satyameva Jayate

References:

- Rao, Seshagiri Ed. & L.M Joshi, ors. Buddhism. Patiala: Punjabi University. 1999

- SarDesai, D.R. India: The Definitive History. Philadelphia: Westview Press. 2005

- Majumdar, R.C. Ancient India. Delhi: MLBD. 2003

- Basham, A.L. The Wonder that was India. Delhi: Rupa. 2010

- Sastri, K.A. Nilakantha. Age of the Nandas & Mauryas. Delhi: MLBD.1996

- Sarma, Nripendra Nath. Ashvaghosa’s Buddhacarita: A Study. Punthi Pustak: Kolkata. 2003

- Mascaro, Juan. The Dhammapada. London: Penguin. 1973