The relations between Raja and Praja are even more important than those between Raja and Mantri and even Raja & Vamsa. Ministers are mere servants of the King and family members should be loyal to the rightful heir and ruler, but the leader ultimately governs for the benefit of the citizen.

This next article in our Continuing Series on Rajadharma investigates the multi-faceted relationship between Raja & Praja.

Introduction

Monarchies come in various forms. The absolute monarchy, however, is the best known and most condemned. So much so is the case that the very notion of monarchy has become condemnable. However, there are other forms. The constitutional monarchy (popular among many “democracies” today) is one such. Then there is the limited monarchy, which some medieval European countries embodied. Then there is the theocratic monarchy. However, the dharmic monarchy in general and the vedic monarchy in particular were none of these.

With any archetype or typology comes attendant risks and ramifications. Too decentralised, and the polity risks incapacity or fragmentation. Too centralised and over-bearing and the danger of tyranny forebodes—after all, not every ruler is a philosopher king. A dharmic monarchy in general and a vedic monarchy in particular, would be both responsive and restrained. It would be responsive to the needs of the populace, restrained in its interference in religious (particularly vedic) matters, but righteous in its willingness to punish injustice in both high and low. What then is the recourse for the praja to petition for justice? To understand this, one must first evaluate the nature of a polity (raashtra) and the nuances in political terminology that are all too often elided.

The Raashtra

“The word ‘rastra’ figures in the Vedic literature as the state of the king, as a territory, desa (country noting a particular region) and pradesa (janapada) with little variations in the context of their meanings and explanations as given therein.” [5, 79]

The raashtra, therefore, does not mean “nation”, as is all too erroneously translated today. So how could “raashtra-dharma” be the culmination of anything?—that is brute statism. The raashtra exists to serve the people, and provide them with Raksha, Paalana, and Yogakshema. One which fails to do so is a failing one or a tyrannical one—probably suitable for those with theocratically tyrannical pretensions.

Raashtra is equated to state/polity per Raamaayana, Kanda 2, Sarga 35, Sloka 20. [1] Valmiki is not alone in this classification and definition. “Vyaasa had distinguished Rashtra from Janapada. The former is the substitute of rajya and the latter stands for its different territorial units. The people inhabiting the rastra have been described in the Mahabharata as rastravasi or rajyavasi. The growth of the state depended on mutual co-operation of its king and his subjects living in different janapadas and puras.” [5, 80]

Raashtravaadha means literal statism and is something that is adharmic by its nature. Bhaarathavarsha refers to the Indic or Indian Subcontinent, and Bhaaratha raashtra refers to the state or polity of India. The Vanga desa or Andhra desa of yester-year are pradesas (provinces) of Bhaaratha Raashtra today. They were referred to as countries not because they were different nations separate from the Indian nation or Bhaaratheeya ethnic stock, but because the nation-state itself is a recent form of political organisation. The Bhaaratheeya janaah (Indian nation) occupied many countries (desas) constituting the subcontinent of India (Bhaarathakhanda), which was a part of the Continent of the Rose-apple vine (Jambudveepa). Desa referred to the land, but Janapaadha referred to the people and the land, and was a portmanteau of people & feet. Today its closest approximation would be the country-side.

Janapaadha (country)→Jaanapaadha (countryside)→Jaanapaadhaah (country-folk) → Jaanapaadheeya (countryish-rustic-countrystyle)

“The people inhabiting a Janapada has been collectively called ‘Janapadaah’, ‘Janapada-nivaasi’ or ‘Janapadavaasi’ and those inhabiting Pura (nagara or capital city) as pura-vaasi, and both were jointly known as “pAurana-Jaanapadah”. [5, 80] If janapaadha refers to a geo-cultural unit or country, then janaah refers to a nation, and janatha refers to a people. Thus, even nationalism, inartfully described as raashtravaadhi today, would be janaahvaadhi.

Ancient Greeks felt they were all one Hellenic nation and rarely organised as a unified empire. What the polis (city-state) was to them, the desa was to the Indian nation, whom they described as the largest ethnos (nation) in the world. It is only during times of national distress or through imperial monarchical ambitions that Indians felt the need to unify—because centralisation inevitably risks tyranny. Diversity is best preserved through de-centralisation; the task lies in finding a balance between the centrifugal and centripetal tendencies in any polity. That requires not only righteous rulers, but also responsible citizens. That is the exigency and obligation today for the Bhaaratheeya janaah.

Historically in India, the King always had an affinity for his subjects as 'my people' & the people had the affinity that he is 'our king'.

— Sage of Kanchi (@haraharasankara) July 19, 2017

“The people of a raastra were called ‘Raastrikas”. V.S. Agrawala, while interpreting the data supplied by Manu has observed that the ‘Raashtra” was a kingdom. It was the ‘collective name of the king’s sphere of administration.’” [5, 80]

The Raaja, therefore, is not subordinate to the Raashtra. He is subordinate to Dharma, which is supreme, and Raajadharma is the embodiment, transcendant and transcendental means of governing the raashtra. A mere state or political unit might have practices—but these cannot contravene Veda in kautilyan fashion. It is the role of the Vedic Raaja to overrule the raashtra’s shaili (custom) if it contravenes Veda egregiously. If it is the role of the Raaja in a Vedic Raajya (as opposed to general Dharma Raajya) to implement varnashrama dharma, then priests cannot be kings, ministers, and generals, and correspondingly warriors, aristocrats, and princes cannot be priests. All too often the degradation of varnadharma is used to justify such overreaches of clerical power, both in toto and in text. But simple lives of scholarship and ascetism is the command for the brahmana, and any privileges ensuing from it.

The only job of a Brahmin is to study and chant Vedas and then to teach Vedas to others. He should not earn money.#Periyava

— Sage of Kanchi (@haraharasankara) January 17, 2017

This is the basis for society’s support and the Raaja’s patronage of priests to begin with—that they do their jobs properly and don’t get involved in politics. One cannot be the moral conscience of the state, people, and society if one is playing puppet-master or malevolent minister. Such misinterpretations and in actuality mala fide manipulations of dharma and saastra have conflated kautilyanism with Krishna’s Raajadharma. This is no doubt the result of materialist kapalikas masquerading as venerable Vaidikas, and perpetuated by useful idiots. Even ostensibly well-meaning scholars of yester-year have erred in their understanding of basic concepts.

“K.P Jayaswal also takes Janapada, raastra, and desa as synonymous. He describes the term Janapada as ‘the seat of the nation.’ True, but ‘Paura-Janapada’ were not the two corporate political bodies or institutions as described by him. “ [5, 83]

“Actually, the raastra in a wider context included pur or nagar, Janapada and nigama or naigama (corporate association of guilds merchants.” [5, 82]

This rectification of raashtra, raaja, and raajadharma was therefore in order so that Raajas of the future (whether constitutionally elected or otherwise) do not become playthings for the amaathyas. As Bheeshma asserted, the purohith and even acharya can be punished if he conspires against the king. The purohith must be a humble well-wisher, and the amaathya and mantri are the servants of the Raaja—then and then only can he play guardian of the praja.

The Praja

“The relationship between the king and his subjects was mainly based on their mutual obligations towards the state.” [5, 42]

The Praja is not without rights in dharmic society. While this may be more obvious in a Ganaraajya (Republic) or Jaanaraajya (Democracy), this is the case even in a Dharmic Raajya. Detaining subjects without cause, punishing them out of petulance, or eliminating them out of tyranny are all barred. The Raaja is expected to wield the sceptre firmly but gently. In light of this, what means of petition does the Praja have in any Dharmic system?

“All men are my children, and I am their father”, thus spake a famous Indic Emperor from Antiquity. But while a Praja’s obedience to a Raaja is expected as a son’s to his father, this obedience is not absolute. While the head of a society or the head of a household should not be serially or needlessly questioned or badgered, when there is due cause to do so, even the humblest may petition the Raaja and ask for redress or explanation from him or a subordinate. This must be done not in the moronically modern, irascibly Indian way of argument to oblivion, but with an attitude of requesting reasonable answer to reasonable question.

“A citizen had the ambition to be the leader of the trade association or of the guild-merchant, failing to be a political leader…The art of peace and the art of war, discipline and perseverance, habits of ruling and being ruled, thought and action, home and state, went hand in hand. A highly practical and keen individual and citizen would have been the result of this life.” [6, 163]

The Raaja

Raajyavrkshasya nrpathimoolam skandhaascha-manthrinaah |

Shaakhaah senaadhipaah senaah pallavaah kusumaani cha |

Prajaah phalaani bhoobhaagaa beejam bhoomih prakalpithaa ||

“The king is the root of the tree of state; the ministry is its trunk; the military chiefs are branches; the army are the leaves of the tree and the subjects are its flowers; prosperity of the country is its fruits and the whole country the final seed.” [5, 30]

As the the head of society, the Raaja is not an ordinary kshatriya, but a ruler of men. Even sages in his domain may thus be sent to him for punishment, as Rishi Likhita was sent to King Sudyumna, in the Mahabhaaratha.[2] But it is best to wield the rod of chastisement lightly. The Raja too, should know when to punish and when to pardon, and when to put aside pride before genuine Maharishis, should they grace the court of mere mortals.

“They say that Raama was the best of the Ikshvaakus on merits; that he was born before Bharata; that he was brave; that he always enquired after the well-being of the Puras; that he took a leading part in the festivities; that he knew the principles of government, etc; that the country desired him as its lord.” [6, 246]

In short, the people do not exist to serve the raashtra, rather, the raashtra exists to serve the people. And the raashtra serves the people when the people either cooperate among themselves or serve the king congenially. Today, people collude with the enemy to serve themselves—and this is celebrated as “Chaanakya niti”…perhaps it in fact is.

As Bheeshma asserted, all things culminate in Raajadharma, as Raajadharma is the culmination of all Dharmas. The Raashtra, the Praja, the Mantri & Amaathya, all are subordinate to the Raaja, who himself is subordinate to Dharma. It is Dharma, and not its mere interpreters, that is Supreme.

“The reason why the sceptre of Hindu sovereign never became the wand of magician, was that the matter of constitutional powers of the king, in fact, lay beyond the province of the ritualist and the priest.” [6, 228]

Rajaniti

“All ancient political thinkers are of one opinion that the primary duty of the king is to protect his subjects by all means because the happiness of the former lies in the happiness of the latter. According to the Mahabharata, the ‘rajasastra’ (on polity and administration) lays great stress on this point ‘The protection of the people of whole state is the essence of rajadharma’. This is what Brhaspati has stated.” [5, 53]

If Raajadharma is about Governance of a Polity, and Raajyasaastra (Arthasaastra) about Statecraft, then Raajaniti is about Politics. At the fulcrum of politics are relations between Raaja and Praja. Simply put, without Politics, neither Statecraft nor Governance can take place. Politics is the grease to the wheel of statecraft, which moves the chariot of Governance. This necessitates not only outreach via grievance mechanisms, but institutional methods for public relations.

Public Relations

“The word Raajan and its origin Raat literally mean a ruler…King is called Raajaa because his duty is ‘to please’ (ranj) the people by maintaining a good government.” [6,183]

The Vedic Monarchy was originally an elected one. In fact, a Song of Coronation and Election is found in the Atharva Veda. [6, 186]

Previous articles discussed how the Ratnavarga or Council of State Gems confirmed the next ruler. The corollary of that is that the Samithi (Popular Assemby) may, in a state of disorder, elect the next king. Invariably, this would be enforced by the Vidhatha (or national executive conclave) consisting of the dynastic leaders, provincial governors, and military generals. But the decision of choosing a king ultimate resided with the people-at-large. A national samithi could and did elect one—particularly in times of trouble.

Hindu Coronation

“Now the chief features of the ceremonies comprised in ‘Hindu Coronation’ are before the reader. In modern language they may be summed up and expressed for the sake of clearness in a few sentences:

(a) Hindu kingship was a human institution

(b) Hindu kingship was elective; the electorate being the whole people.

(c) Hindu kingship was a contractual engagement.

(d) Hindu kingship was an office of State, which had to work in co-operation with other officers of State.

(e) Hindu kingship was a trust, the trust being the tending of the country to prosperity and growth.

(f) Hindu kingship is expressly not arbitrary. [6, 211]

(g) Hindu kingship was not above the law [i.e. dharma] but under it.

(h) Hindu kingship was primarily national and secondarily territorial. ..The Hindu race did not care solely for the world after. ” [6, 212]

The Monarch and his consecration was therefore vesting in the Raaja a trust that he would govern in the interest of his praja. In the Sathya, Treta, and the Dvaapara Yugas, the Raaja was expected to not only come from the Kshatriya Varna, but was to hail from those born Kshatriyas anointed as Raajanyas.

“The idea is that the Brahmin may not now be addressed by his privi-leged designation of superiority. The superiority which is given to the king by the whole nation including the Brahmin makes the Hindu king legally and constitutionally superior to all classes and castes.” [6, 210]

However, as Bheeshma asserted in the Raajadharma Anusaasana Parva, in the Kali Yuga, in a time of Apat (Emergency and Disorder) a legitimate Hindu King capable of providing security for the native inhabitants could come from any varna. [2] This is not pretext for foreign rule, but in fact, expressly asserts the need for native ethnic origin.

“a king to be a legal sovereign must receive his royal conse-cration. The Puranas called foreign barbarians of the sixth century ‘naiva-moordhaabhishiktaas-te,’ ‘unconsecrated heads.’ i.e., ‘usurpers'” [6, 223]

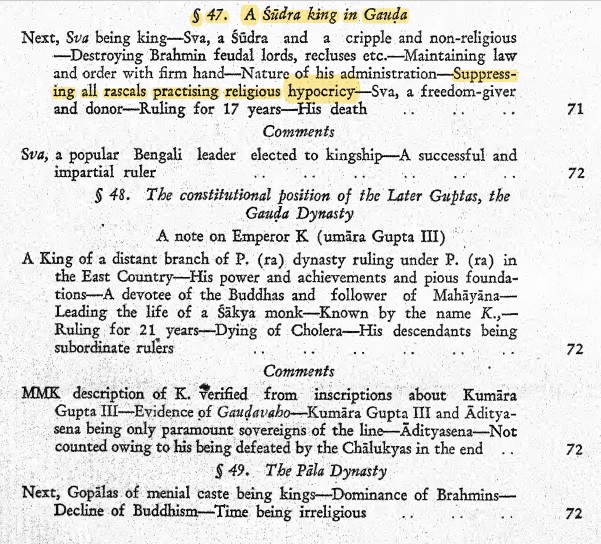

In such difficult and complicated times, election of Kings from among the masses became inevitable. However, they would have to eventually initiate as kshatriyas (of new vanshas, i.e Agnivansha) rather than continuing connections with purvashramas. But the popular election of Kings is lauded. Even the Puraanas assent to this:

‘The Devas and Asuras were fighting….the Asuras defeated the Devas….The devas said, ‘It is on account of our having no king that the Asuras defeat us. Let us elect a king.’ All consented.‘” [6, 184]

Elected Kings

“The king was elected by the people assembled in the Samitee. The people assembled are said to elect him according to rulership unanimously. The Samitee appoints him. He is asked to hold the state. It is hoped that he would not fall from his office. He is expected to crush the enemies.” [6, 186]

As discussed in Governance & Administration, the Jaana Samithi was an important institution. Translated as Popular Assembly, it was typically called by the Govikarthr, the Mayor, or the King himself. “The word Samiti (sam + iti) means ‘meeting together,’ i.e., an assembly. The Samiti was the national assembly of the whole people or Visah; for we find the whole people’ or Samiti in the alternative electing and re-electing the Raajan or ‘King’. “[5, 12]

Elected Kingships are therefore not unknown, and are documented also by foreign observers.

“Megasthenes notes that after Svayambhoo, Buddha and Kratu, the succession was generally hereditary but that ‘when a failure of heirs occurred in the royal house, the Indians elected their sovereign on the principle of merit.” [6, 185]

For those who believe that Raajadharma applies only to Raajas, here are some facts: First and foremost, even in traditional Vedic monarchies, the rules of Raajadharma extended not just to Raaja and Yuvaraaja, but also to Mantri, Pramukha, Mandalesvara, Panchayat, and Praja. Second, the elected Raajas for Ganasanghas (Republics/Oligarchies) also had to follow Raajadharma and were even styled as ‘Raajas’ (though Eeshaana or Rashtrapathi is preferred). It is for this reason Raajadharma is best translated as Dharmic Governance.

“For providing equal justice to all the members of the society, for peace, progress and prosperity of the people, for the welfare of the state or raastra, for an efficient administration, to protect the weaker sections of society from stronger one, to punish the offender and finally to keep everyone within the limits of ‘Dharm’, a ‘Dhanda-neeti’ (law) was framed and the king also known as ‘Dhandakartaa’ or ‘Dhandadhara’, was invested with power to enforce it” [5, 40]

Public Persona

राजप्रभावजुष्टाम् हि दुर्वहामजितेन्द्रियैः |

परिश्रान्तोऽस्मि लोकस्य गुर्वीं धर्मधुरं वहन् || २-२-९

“This burden of worldly righteousness is very heavy. This can be sustained only by royal power with qualities like courage and valor. A person who has no control of senses can not carry this burden. I have become tired while carrying this burden of righteousness. ” [1]

The position of a King is a burdensome one. Indeed, that of any political leader, whether democratically elected or royally selected, necessitates sacrifice of certain freedoms. Political life invariably places restrictions on private life. As such, a suitable leader, whether Raashtrapathi or Raaja, must play the role of a responsible first citizen in public—and ideally, even in private.

Sloth, slovenliness, selfishness, stupidity, all are behaviours which are criticised in prajas but outright condemned in Raajas.

Members of a Royal or Noble family are expected to show the refinement of Aristocracy as well. If the Royal Qualities represent the soul, then refinement represents the alankara.

- Sishta—Good habits & traditional discipline. Spiritual living & observance of custom

- Sthirasamskaara—Very Cultured

- Basic understanding of Dharma, Niti & Itihasa

- Skilled in 1 or many Arts and/or learned in Literature

- Trained in Dhanurveda as well as 1 or many types of self-defence

- Fashionable in Dress & Appearance

Public Recourse

Raja exists for Praja, not the other way around.

Dharma is supreme. The King is second to Dharma and must uphold it. He is to be honoured.

Raaja Ratnas only anoint & crown King if vacancy/ petition. Ratna varga has no other power. It is assembled by the incumbent Purohith.

King can arrest any member of society, but must formally charge them with legal aparaadha.

Ministers and others must give the king benefit of doubt. If he engages in terrible adharma, the following consecutive actions can occur:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lj0oPAHbrLI

- Mantrins can vote in Parishad before the king to express concern at current course

- If King proceeds without justification, 1 or several Srothriya Brahmanas to be invited before the King at the Sabha to explain correct raajadharma

- Mantrins can resign in protest (like Vidhura) [2]

- If King continues arbitrary/oppressive behaviour, Vidhatha may vote to censure/depose

- If King’s misbehaviour continues, Jaana Samithi can be called to vote to depose the King

It is only after these five steps over the course of a month or year that a resolution to depose the king can be brought before Raaja Ratnas. The Vidhatha’s motion to depose is to be brought to the Jaana Samithi by a senior member of the Vidhatha. Motion to depose should take place not more than once in 5 years. If no eligible member of the present dynasty can be anointed, then only can a qualified Kshatriya of Raajanya rank can be nominated. A rebellion to chastise but retain the king is an option. A revolt to overthrow/imprison is the next course to be followed. Civil war should be avoided. Coups, particularly involving foreign interference and foreign rulers, are worst of all and condemnable. If no qualified Kshatriya can be found, qualified Vaisyas or Sudras capable of providing security may be considered. Brahmanas were not ideal candidates for kingship or ministership.

The Jaana Samithi is to be organised in the National Capital Region by the Capital Mayor. Any official member of the Jaana Samithi can bring forward a motion, to be voted on for acceptance or rejection. The Govikartha is Jaana Samithi Chairman, and cannot adjourn until there is a motion to adjourn. Failing that, lesser Praja Samithis can be organised by an administrative head at district level (Naadu), province level (Pradesa), & territorial level (Visaya). It is better to suffer under a bad native king than to risk or invite foreign rule. Regicide is to be avoided unless foreign rule or destruction of society becomes obvious, and is at hand.

Deposable Offences:

- Tyrannical oppression of the Populace for years

- Targeted, deliberate, and consistent destruction of Stree-Go-Braahmana

- Mass Murder of Innocents

- Debased rule and obvious foreign, especially mleccha, interference

- Plunder of the populace through overwhelming taxation & enslavement

A change in the system of government should be the last option. The Licchaavis famously drove out the kings of Videha and established a system of Ganaraajya (Republic). Jaanaraajya is rule by the people through voting or popular election of representatives.

Conclusion

Raajadharma is not a pass-time for the petulant nor a conspiracy for kautilyan con-artists. It is very serious business, and it is long-past time that Bhaaratheeyas start behaving like a serious people. Playing Stree-go-braahmana prathipaalaka is not for the infantile or petty, but a matter of manly resolve, principled conduct, and pragmatic public interest. Any murkhapanditha can “do strategery” to win today, but lose tomorrow. Those who have skin in the politico-strategic game are better aware of how kootaniti must actually be conducted. It may seem well and good to irresponsibly declare one’s intentions or attack fellow citizens in a time of disorder, but Raajadharma and the relations between Raaja & Praja recognise fully how the raashtra exists to bring all raashtrikas along, and that the conduct of state business must take place responsibly—not selectively.

State as religion is adharma. Be it under the moniker of “raashtra dharma” or the misnomer of “raashtravaadha“, either of these two clerical franken-concepts result in prajavadha. It is imperative for people to recognise that Dharma is not merely a means to rule over citizens, but is the source of harmony for all society.

Selective information, selection bias, and confirmation bias rule the day, creating outspoken imbeciles, self-interested amaathyas, but few if any dharma raajas or even dharma pramukhas. When the masses behave irresponsibly, when educators behave irresponsibly, then it becomes incumbent upon those with leadership potential to not only call for responsible behaviour, but also to enforce and embody it. It is for this reason that raajadharma does not nor can ever culminate in raashtra-dharma [whatever that is…], but rather that Raajadharma is the embodiment and wellspring of all dharmas.

The importance of Raajadharma in protecting and governing all other castes:

Bhishma also said O, King, just as the foot of an elephant covers every other foot, so does Rajdharma cover every aspect of Dharma, in all conditions. Among all Dharmas, Rajdharma is supreme, as it provides nourishment to people of all Varnas (professions). Rajdharma encompasses all sacrifices. The sages, since ancient period, praise sacrifice as the best form of Dharma. The Sanatan Dharma got destroyed hundreds of time, but (each time) it was redeemed and spread again by Kshatra-dharma. In every age, Kshatra-dharma has to be active. Therefore, Kshatra-dharma is the best in the world. Sages praise sacrifice or renunciation, but the greatest sacrifice is that of the kings who lay down their body in fulfillment of their Raj-dharma.

References:

- The Ramayana. http://www.valmikiramayan.net/

- The Mahabharata. http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/m12/

- Singh, G.P. Political Though in Ancient India. New Delhi: DK Printworld. 2005

- Jayaswal, K.P. Hindu Polity: A Constitutional History of India in Hindu Times. Delhi: Chaukhamba Sanskrit Pratishthan. 2005

- Jayaswal, K.P. An Imperial History of India. Lahore: MLBD. 1934