For all the talk of decoloniality, one of the most colonised areas of the modern Indic mind is dimensionality. Specifically, Indic Weights & Measures have long been forgotten by the masses at large, and even most of our “intellectuals-yet-idiot”. While it is important to navigate the modern world, it is even more critical to remember where we came from. Pauthavam is one means of doing so, and measuring exactly how far we’ve come and how much the weight has been.

Measurement was known by many names in Ancient India. However, a degree of precision is necessary whilst classifying terminology. For the sake of simplicity, Thaalamaana refers to measurement, Parimaana refers to dimension, and Pauthavam refers to Weights & Measures.

” When dharma took a backseat, trust in the contextually flexible and versatile Rajju was lost and people returned to a rigid and inflexible ruler.” — Shivoham

Terminology

- Pauthavam—Weights & Measures

- Parimaana—Dimension

- Thaalamaana—Measurement

- Bhaara—Weight

- Aadhama/Aayaama—Length

- Rajju—Measuring String

- Kaala/Samaya—Time

- Thulabhaara/Samavrthhaa—Balance/Scale

- Chhaayaanaalikaprathodena—Day hours per shadow-measuring

- Dhaaraka—Weigher

- Maapaka—Measurer

- Dhaayaka—Distributor

- Dhaapaka—Load Carrier

- Salaaka-prathigraahaka—Counter of Tallies

- Prahala—Acre

- Kashtam—Wood

- Dirghachaturasra—Rectangle

- Akshnaya Rajju—Diagonal [6]

- Chaturasra/Samachaturasra—Square

- Tiryanmaani—Perpendicular (north-south)

- Lekha/Rekha—Line

- Rju-lekha—Straight line

- Varga—Unit Square (to compute area)

- Krithi/Varga—Square of any number

- Karani—Side of the square, square root [7]

Units of Scale

Weights and measures cover a myriad of matters running from the eponymous, to time, area, and even temperature. Some things we know for sure our ancestors calculated with ease, some, not so much. Irrespective, in order to properly determine weights and measures, a logical system of counting becomes imperative.

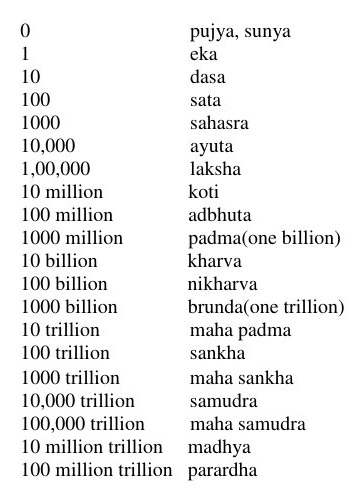

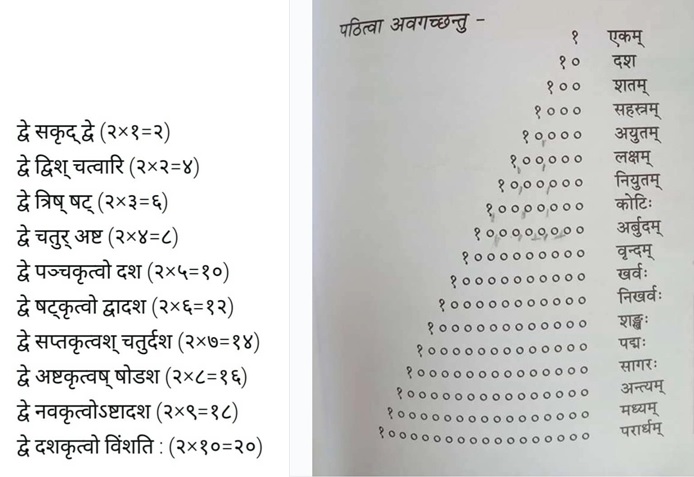

Units of Scale are crucial to understanding the sheer magnitude of a thing, which is often calculated in orders of magnitude. The myopic mind might have resort to roman numerals to calculate tallies, but to appreciate the grandeur of the cosmos takes talent that thinks in the trillions and 100 trillions. Ancient Hindus did just that.

Of course, the western academy as usual dilutes the Indic component of anything and hyphenates it as it does in all things—in this case, with the erroneous “Hindu-Arabic Numerals”. When pressed, hairsplitting and obscurantism is conducted (i.e. “well, you’re right, except here we are referring not to the numerals but to the glyphs”). This as though a mere minor change in the stroke of a symbol somehow birthed a new typology…

Nevertheless, the use of Hindu numerals to conduct Hindu calculations makes Classical Indic Weights & Measures that much more Hindu. Familiarity with this will facilitate the traditional standardised system of weights and measures, i.e. Pauthavam.

Units of Measurement

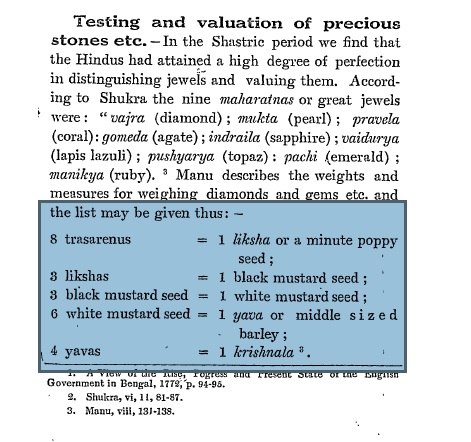

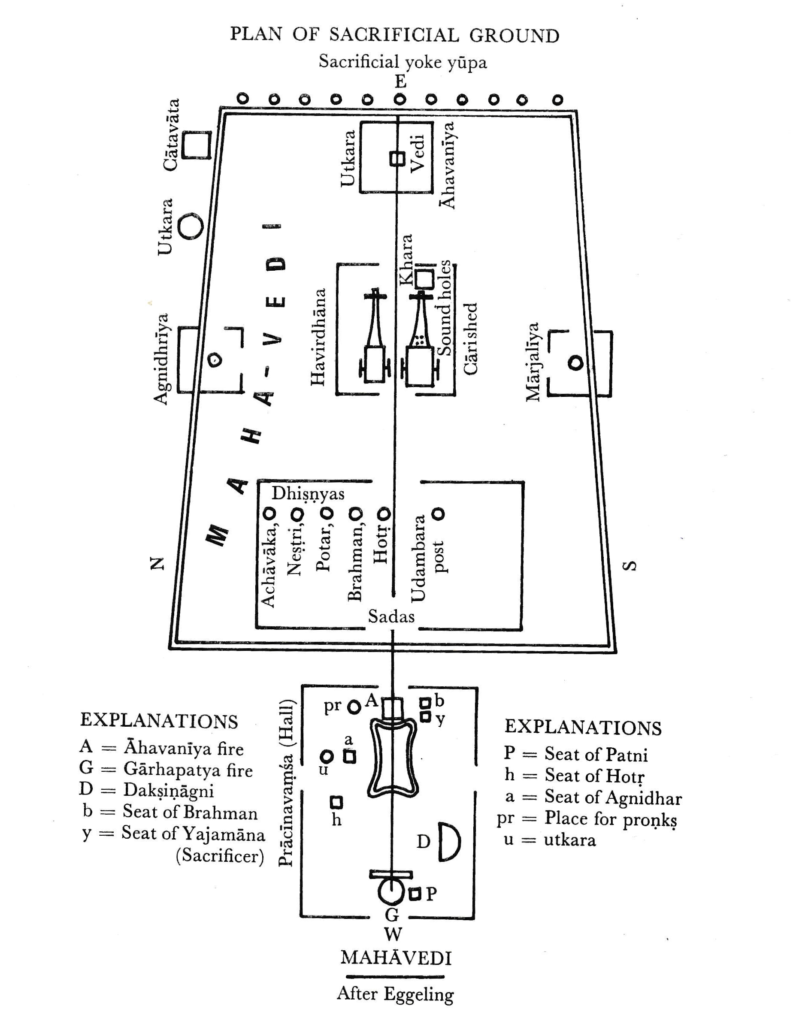

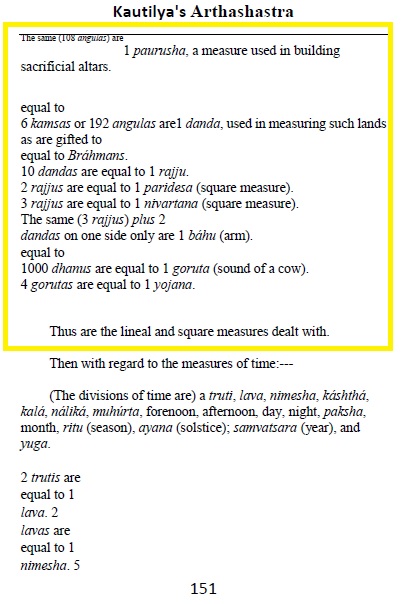

[2, 153]

[2, 153]

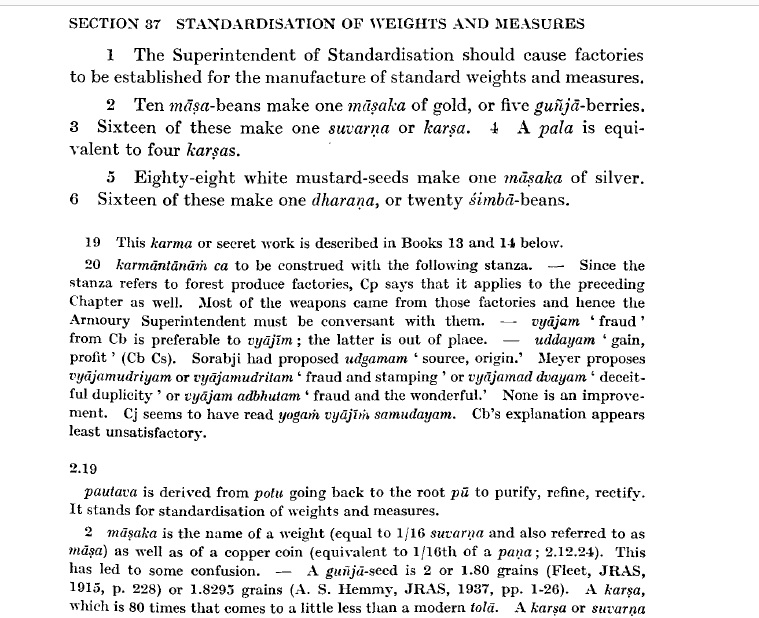

The Arthasaastra of Kautilya is merely one of many texts on the topic of Raajyasaastra (Statecraft), one of the main topics under Rajadharma (Governance). It is erroneously touted as a pioneering invention (Narada & Brhaspathi beg to differ) and the authoritative text on Raajadharma (it’s not, see Mahabhaaratha and Raamaayana). And Kautilya was certainly no Rishi (in fact, just the opposite…), unlike venerable Maharishi Vaishampayana. In fact, tradition holds that Kautilya himself corrupted Raajadharma out of petty revenge against the Imperial Nandas. For this reason, he is neither a pioneering empire-builder nor a role model.

However, he did do a fine job of documenting the previous knowledge accumulated by Brhaspathi, Sukra, Narada, and Bheeshma, and similar to the Acharya of the Asuras, should be seen as a source of statecraft learning rather than moral governance. Naturally, a Standardised System of Measurement was necessary across any well-organised polity (raashtra). It is here that the Arthasaastra, Maanava Dharma Saastra, and Baudhayana Sutra (among others) are all edifying.

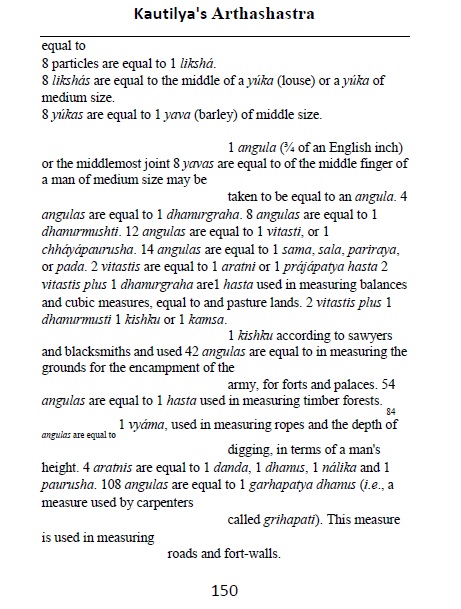

Surprising to many, the Indic system of measurement starts with the atom as the smallest unit of measurement. Even in our age of subatomic particles, it becomes astounding that atoms were not only conceived of, but conceived as the base unit of measure almost 3000 years ago. Discrepancies aside, some consistencies remain apparent. For the sake of consistency, one will consider the comparison of atom (paramaanu) to angula (finger-breadth). As per L.N. Rangarajan, 1 angula = 32,768 paramaanus. [4, 373] However, he uses base 8 for all the relations, which Kangle and others do not.

The Units of Measurements commence with the atom, per Kangle.

- 1 atom = 1 paramaanu

- 3 paramaanus = 1 raja.

- 8 rajas = 1 roma

- 8 romas = 1 liksha

- 8 likshas = 1 yooka

- 8 yookas = 1 yava

- 8 yavas = 1 angula

- 2 angulas = 1 golaka

- 2 golakas = 1 bhaaga (i.e. part)

Units of measurement used in the Baudhayana Sulbasutras [7]:

- anima pada = 10 angulas

- pada = 15 angulas

- aratni = 24 angulas

- prakrama = 30 angulas

- aksha = 104 angulas

- vyama = 120 angulas

*(linear) purusa = 120 angulas

Manava Dharma Saastra provides a modified system.

Weight

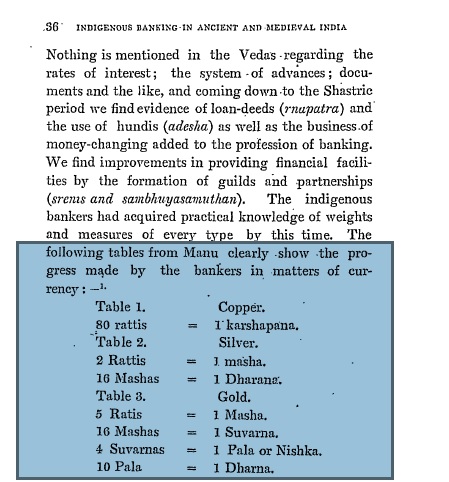

[8 ,36]

[8 ,36]

Weight and value do not always align, but nevertheless, closely intertwine.

For example, the value of 1 oz coin of Gold to 1 oz coin of Silver & 1 oz coin of Copper is as above: 1:16:80

However, the weights may be different

1 maashaka of Gold to 1 maashaka of Silver to 1 maashaka of Copper is 5:2:5 rattis.

1 ratti is an individual rice grain of the same size. 8 rattis = 1 maasha

1 maasha is 1 black bean, per Rangarajan [4, 767]. A maashaka is therefore a weight based on that bean. This naturally lends a whole new meaning to the modern phrase “bean-counter”.

The three respectable translations of the Arthasaastra are by Shyamasastry, Kangle, and Rangarajan. Each contribute valuable aspects of both weight and value. Nevertheless, it must be adumbrated that there are inconsistencies in the measures and equivalencies across their books. Whether this is due to a disparity in translations, calculations, or recensions is another matter altogether.

- 20 rice grains (rattis) = 1 dharana

- 16 maashakas = 1 karsha

- 4 karshas = 1 pala [4, 767]

- 10 maasha beans = 1 gold maashaka = 5 gunja berries

- 16 gold maashaka = 1 gold suvarna or karsha

- 4 gold karsha = 1 gold pala

- [8 maasha = 4 gunja= 1 simba = 2 silver maashaka]

- 4 maasha beans = 1 silver maashaka = 2 gunja berries = 4/5 simba beans

- 16 silver maashaka = 1 silver dharana or karsha = 20 simba beans

- 4 silver karsha = 1 silver pala [2, 178]

- 1 pala = 4 karshas, 88 mustard seeds = 2 gunjas

- 1 silver maashaka = 2/5 gold maashaka. [3]

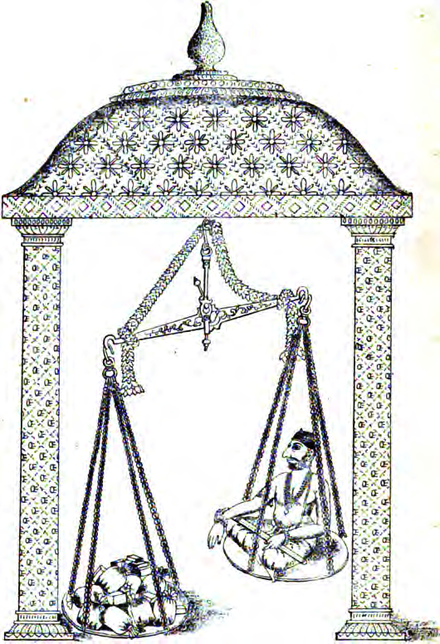

Finally, of tremendous weight is actually having a functioning mechanism for weight measurement. A famous episode in the Mahabhaaratha (Sri Krishna Thulabhaaram) illustrated this.

The historic scale (parimaani) was 96 angulas in length. Markings were made for 20, 50, 100, 200 palas. Each bhaara weight was equal to 20 tulas. 10 dharanas made 1 pala.

“part of the lever where, held by a thread, it stands horizontal). To the left of that mark, symbols such as 1 pala, 12, 15 and 20 palas shall be marked. After that, each place of tens up to 100 shall be marked. In the place of Akshas, the sign of Nándi shall be marked. Likewise a balance called parimání of twice as much metallic mass as that of samavrittá and of 96 angulas in length shall be made. On its lever, marks such as 20, 50 and 100 above its initial weight of 100 shall be carved.

20 tulas == 1 bhára.

10 dharanas == 1 pala.

100 such palas == 1 áyamání (measure of royal Public balance (vyávaháriká )” [3, 146]

Maanava Dharma Saastra bases the determination of weight on the rakthikaa (bright red gunja seed). This resulted in the following system:

- 5 rakthikaas = 1 maasha

- 16 maashakas = 1 karsha, tolaka, or suvarna

- 4 karsha = 1 pala

- 10 dharana = 1 pala

- 16 palas = 1 prastha

- 4 prasthas = 1 aadhaka

- 4 aadhakas = 1 dhrona

*1 karsha = 1 ounce

Equivalency

- 1 dharana = 230 gunja berries or 640 maashas

- 10 dharanas = 1 pala = 1 ¼ oz = 35 gm

- 100 palas = 1 tula = 7 ¾ lbs = 3.5 kilos

- 20 tulas = 1 bhara = 154 lbs = 70 kilos [4, 767]

Length

Length was based on the barleycorn (yava), paralleled by finger breadth (angula) and hand length (hastha). As discussed extensively in this exquisite series on Sulba Sutra, Indic measurers had a measure of intellect sufficient to realise that length is better measured through a flexible rajju than a rigid ruler. Mechanisms of measure and units of measure aside, below is the system of length measurement proper.

- 8 yava = 1 angula

- 12 angulas = 1 vithasthi

- 2 vithasthis = 1 hastha/arathni

- 4 hasthas = 1 dhanda/dhanush

- 2,000 dhanus = 1 krosha/goruta

- 4 krosas = 1 yojana

Here, the relationship between angula and dhanus is 96:1. Elsewhere, there is a different measurement:

“length (aayaama)

dhanus = 108 angulas

one danda (6 ft.)

a krosa (2250 yds or 6750ft)” [ 3, 150]

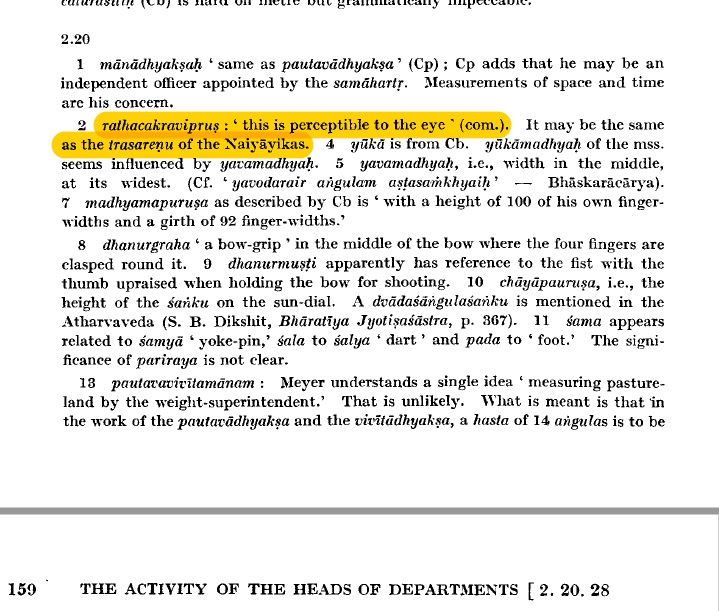

There is some discrepancy over the actual length of these units of distance. Across texts the relations sometimes vary (i.e. sometimes 24 angulas for a hastha other times 21, etc). This is most disconcerting with respect to that famous furlong (or mile if you prefer) known as the yojana (which actually equated to ‘league’). If one considers the details, some elucidation occurs. For example, as erroneously proffered by indologists, 1 hastha is not a cubit (aratni). It is not even 1 human hastha (hand), but the hastha of Prajapathi (the Divine Progenitor). To round out the measures, just as a paramaanu is an atom, a liksha is a nit (or poppyseed), a yooka is a louse, and a yavamadhya is 1 barleycorn middle. Per this edition, 1 angula is the width of a middle part of a middle finger, with four of these making 1 dhanurgraha (1 bowgrip).

However, 1 width of the middle part of a middle finger approximately measures 0.75 in. How can this, therefore reduce down to 8 barleycorn middles? At 0.33 in would make for roughly 2.5 in (almost triple). So something is off.

One matter of interest is that 1 rathachakraviprus is the smallest particle visible to the eye. Clearly, an incisive level of observation was taking place.

“Various estimates of its size [the Earth] were made, the most popular being that of Brahmagupta (7th century A.D.), who gave its circumference as 5,000 yojanas. Assuming Brahmagupta’s yojana to be the short league of about 4 1/2 miles, this figure is not far out, and is as accurate as any given by ancient astronomers.” [5, 288]

The colonial period often featured some ham-fisted attempts at false equivalency, under the pretext of ‘rationalisation’ of force-fitting terms under Imperial Standard measures (i.e. hastha and cubit (distance between tip of finger and elbow)). However, hastha translates specifically to hand and bhuja to arm, thereby disqualifying that measure.

It should also be noted that the Imperial and even ye olde English System of Measures (itself originating in the Roman) are curiously based on the barleycorn (0.33 inches) as the base unit. The relations between inches and feets, yards, miles, and even leagues cannot be ignored or taken as unrelated. But it also brings to question whether the angula (not equated to an inch) can be based on the barleycorn (very convenient). After all, if a barleycorn is a yava, then 8 of those equates to 2.5 inches (well over the 0.75 inches attributed to the angula at the largest).

Perhaps there is another equivalent for the yava. The yojana is also thrown off, with some equating it to 9.5 miles and Basham above equating it to 4.5 miles. Irrespective, reconciliation between these inconsistencies will have to occur at some point. Perhaps, this is all indicative of some other phenomenon altogether. Either way, something clearly is afoot (bad pun, I know…)

Area

- 1 dhanda = 1 standard brahmadheya land grant

- 1 rajju = 10 dhandas

- 1 nivarthana/baahu = 3 rajjus

- 1 kulyavaapa = 8 dhronavaapas = 13 nivarthanas

Thus, dhanda, rajju, nivarthana, and kulyavaapa are the proper units of measure for area.

Equivalency

- 1 dhanda = 1152 sq ft = 128 sq yards = 0.026 acres = 107.031 sq metres

- 3 rajjus = 32,000 sq ft = 3600 sq yards = ¾ acre = 1/3 hectare

- 1 baahu = 32 dhandas = 4096 sq yards = 3425 sq metres = 0.85 acres = 0.35 hectares

- 1 nivarthana = 1 square of sides = 3/4 acre = 32,400 ft = 3000 sq metres

- 1 kulyavaapa = ~ 421, 200 sq ft = ~10 acres = ~4 hectares [4, 765]

*1 acre = ~43,560 sq. ft sq ft

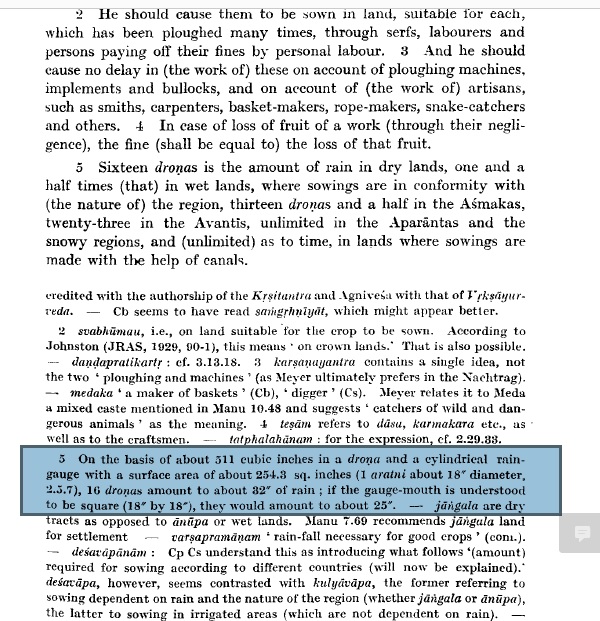

Volume

One would think there would be volumes on volume. However, textual evidence is not so voluminous, but not so scarce either. The Arthasaastra of Kautilya proves illustrative here, and provides the following system of cubic measures to determine capacity.

- 4 kudubas = 1 prastha

- 4 prasthas = 1 aadhaka

- 4 aadhakas = 1 dhrona

- 16 dhronas = 1 khari

- 20 dhronas =1 kumbha

- 10 kumbhas = 1 vaha (cartload) [4, 766]

*200 palas of maasha beans make 1 prastha. 25 palas of firewood cook 1 prastha of rice.

Equivalency

- 1 dhrona = 511 cubic inches

- 1 khari = 8, 176 cubic inches

- 1 kumbha= 10, 220 cubic inches

- 1 vaha = 102,200 cubic inches

Time

[Formatting and Proofing ours.]

According to the Smritis,

- 18 winks of the eye = 1 kastha

- 30 kasthas =1 kala

- 30 kalas =1 muhurtha

- 30 muhurthas =1 day and night.(This Ahoratree is the human day.)

- 6 respirations = 1 vighati

- 60 vighatikas = 1 ghatika

- 60 ghatikas = 1 day and night (This Ahoratree is the human day.)

- 15 days = 1 paksha

- 2 pakshas = 1 human month

[Indic Epistemology is invariably tied to the spiritual. While materialists may dislike the inclusion of Vedic Cosmology, Dharmic Time-keeping is invariably steeped in spirituality]

1 human month = 1 day and night: of the Pitris (Manes), the Sukla paksha being their day and the Krishna paksha being their night.

12 Human months or one year = 1 The Ahoratree of the Devas

6 Human months = 1 ayana, ( From Pushya to Jyesta is day of the Devas, from

Ashadha to Margasira is night of the Devatas.

30 human years = 1 Month of the Devatas.

360 human years or 12 Daiva months = 1 Year of the Devatas

12000 Daiva years or 43,20,000 Years = 1 Daiva yuga or ordinary Mahayuga

0.4 Mahayuga = 4800 Daiva years = 17,28,000 years = Kritayuga (yugasandi & Sandhyamsa).

0.3 Mahayuga = 3600 Daiva Years = 12,96,000 years = Tretayuga

0.2 Mahayuga = 2400 Daiva Years = 8,64,000 years = Dwaparayuga

0.1 Mahayuga = 1200 Daiva Years = 4,32,000 years = Kaliyuga

1 Mahayuga = Kritayuga + Tretayuga + Dwaparayuga + Kaliyuga

1000 Daiva Yugas or ordinary Maha Yugas or 432 crores of ordinary years = 1 day time for Brahma. This is Udayakalpa. = 30 Ghatikas for Brahma.

Another 1000 Daiva Yugas or 432 crores of ordinary years = Night for Brahma or Kshaya kalpa

2000 Daiva Yugas or ordinary Maha yugas i.e., 864 crores ordinary years = 1 Brahma Ahoratree.

30 Ahoratrees of Brahma or 6,000 ordinary Mahayugas = 1 Month of Brahma

12 such Brahma months = 1 Brahma year.

100 Brahmaic years = Life period of Brahma.

During the day time of Brahma (1000 Mahayugas) , 14 Manus look after this world. Each Manu reigns 71 Mahayugas . In the first day of the 51st year of Brahma have rolled away the following periods:

6 Manus = 6 x 71 = 426 Mahayugas = 184,03,20,000

27 Mahayugas of the period of Vivasvata, the seventh Manu = 11,66,40,000

The Kritayuga of the 28th Mahayuga = 0.4 Mahayuga = 17,28,000

The Tretayuga = 00.3 Mahayuga = 12,96,000

The Dwapara = 0.2 Mahayuga = 8,64,000

The Kaliyuga till (Kali 5056 or 1955* A. D.,) = 5,056

__________________

Total.= 426+27+0.9 Mahayugas + 5056 years = 196,08,53,056 years

___________________

7 Jalapralayas = Kritayuga = 7*0.4 Mahayugas =2.8 Mahayugas = 7 * 17,28,000 = 1,20,96,000

_________________

Total. 197,29,49,056 years *

_________________

1955 A. D. This is recorded in our Panchangas year by year.*

Age of the Universe per Pandith Kota Venkatachalam based on Traditional Vedic Reckoning per Jyothihsaastra.

[End Section]

Conclusion

In Sulba Vijnana itself, the contextually flexible and versatile Rajju replaced the rigid Bamboo rod (Venu) as a preferred means of measurement.

Corruption during Mughal occupation brought back rigidity in so many ways. pic.twitter.com/hJ6MZFoIAO

— Shivoham (@Ganitamrita) March 14, 2018

As usual, according to the secular school of saastra, “yeverything kayme from mughal”. As such, measurement today is stupidly seen as pre-and post-akbar. In reality, the system of measurement is far more ancient than given credit for. Indeed, the mughal kos quite obviously came from the classical indic krosa found in Arthasaastra. Tol clearly comes from tula.

But the cognatic relations don’t end there (pun intended). The roman uncius (root of English inch) means finger in latin, corresponding to the indic angula (finger breadth in Sanskrit). This is mirrored by the world yava (Sanskrit for barleycorn). Incidentally, this barleycorn (0.33 in) is the root measure of the English System of Measurement. Proto-Indo European advocates may quickly called for a ‘yamnaya’ system of yava measurement, but the reality is obvious.

These measures are all found in the Hindu epics long before ancient Rome, and unlike ancient Egypt, Ancient India already had a sophisticated system of numbers, making importation of weights and measures even less likely. If anything, one could easily claim the reverse. Then there is the question of Sumeria and its ancient links with Harappa. It is clear that further investigation is required to understand the relationship between all these systems, as well as reconciling equivalency tables with the modern metric system.

Units of measure come in myriad forms and purposes. From length and height to time and temperature, the list is copious. In the present time, new units of measure are being invented all the time, as Galileo, Kelvin, and Curie can all attest. While it is important to keep up technologically, and practical to think rationally and metrically, it is also critical to have a local lens on how to view, weigh, and measure the world. Empires rise and fall, systems come and go, but some systems of measure stay the same irrespective of time, age, yuga, or kalpa.

References:

- Kota Venkatachalam, Paakayaji (Pandit). The Age of the Mahabharata War. Vijayawada: Tirumala.1988

- Kangle, R.P. The Kautilya Arthasastra. Part II. University of Bombay. 1963

- Shyamasastry, R. Kautilya Arthasastra. Govt Press. Bangalore. 1915

- Rangarajan, L.N. Edit, Kautilya. The Arthashastra. New Delhi. Penguin.1992

- Basham, A.L. The Wonder that was India. New Delhi: Rupa.1999

- Shivoham. “Sulba Sutra”. Indic Portal. https://indicportal.org/sulba-sutras-the-indic-approach-to-engineering-1/

- Shivoham. “Sulba Sutra”. Indic Portal. https://indicportal.org/sulba-sutras-the-indic-approach-to-engineering-2/

- Bhargava, Brijkishore. Indigenous Banking in Ancient & Medieval India. Taraporevala & Sons. Mumbai. 1934

Excellent post. Keep up the good work.