After a long hiatus, ICP returns with an article on a key historical and philosophical figure. Often times, the theoretical intersects with the biographical. One such figure with an emblazoned imprimatur on Indic Logic was a studious Buddhist stalwart. Indeed, he made a name for himself by making an effort to separate the nettlesome Indian penchant to forever fuse logic with argumentation.

In the name of disputation, modern Indians have forgotten that the aim of logic is not assert your will or view (however imbecilic) upon the opponent, but rather, to jointly ascertain the truth. In this unwillingness to collaborate internally, truth has gone for a toss, and the masses are mired in a miasma of moronery. Therefore, study of this scholar is of import in this next installment of our continuing Series on Buddhist Personalities: Dignaga

Background

“Dignaaga was converted to Buddhism at an early age by a teacher of the Vaatsiputreeya sect and took the vows from him. But on certain points he could not agree with his teacher and left his monastery. Later he became the disciple of Vasubandhu and in the study of the science of logic he advanced further and attained great fame. [1, 87]

Alternately known today as Dinnaaga or Dignaaga, the original Sanskrit form of this personage’s name was Dheerganaaga. For the sake of simplicity and continuity, we will retain the modern phonetic spelling of Dhignaaga.

“One of the greatest Vijnaanavaada writers who lived in Andhra was Dignaaga, ‘He was master mind’ and one of the foremost figures in the history of Indian philosophy. He was a disciple of Vasubandhu. Dignaaga was mostly an independent thinker among his successors. Dignaaga was regarded as the father of Buddhist logic. He was a great celebrity in disputations with opponents. Dignaaga became one of the most powerful propagators of Buddhism.” [1, 86]

Nevertheless, as with all popular figures, there is a penchant for parochialists to claim them for the posterity of their provinces. Indeed, in the present time, one may find even other nationalities attempting to claim India’s Buddhist heritage and philosophy as invented by them. As such, it is imperative to set the record straight. Bhaaratheeya Bauddhas and Vaidikas alike have an interest in seeing our progenitors get due credit for their achievements. It is also critical to ensure that the philosophy is correctly understood and passed on.

However, the dating of such figures is often even more controversial. Dhignaaga’s association with Vasubandhu would indicate a life in the era of the Gupta dynasty, which is dated to the 4th Century BCE per Indian Puraanic Chronology and 4th Century CE per Western academia. “Most scholars are of the view that Dignaaga lived about the 6th century A.D.” [1, 86]

Then there is the question of the where. As previously discussed, although this writer hails from Aandhra, it is important to lead by example and not claim all figures as Aandhra brahmins, as has been done with Nagarjuna and, in this case, Dhignaaga. While the Satavahana dynasty certainly was Aandhra brahmin in origin, Nagarjuna, per the Rajatarangini, was a Northern Kshathriya. Dignaaga, on the other hand, is a bit more nebulous in natality.

The general consensus among scholars is that he was born at Kanchi. But the Tibetan tradition says that he was born at Simhavaktra near Kanchi. Simhavaktra is identified with Vikrama-simhapura of Nellore. The Tibetan tradition further says that he lived on Borasaila in Orissa, whereas Yuan Chwang associates him with Aandhra.” [1, 86]

“There might be truth in both the traditions as the regions are contiguous. The account of Yuan Chwang is that he saw a Sanghaaraama on a hill 200 li further south-west of Ping-ki-lo (Vengi), the capital of An-to-lo (Aandhra). On the ridge of this isolated hill was a stone tope where Dignaaga (Channa) Poosa lived and composed a treatise on logic. That Vengi is no doubt a Buddhist Kshetra, is established by the recent discovery of the ruins of a big stoopa and other antiquities. However, Guntupalli where there are a rock-cut caitya and vihaara answers well the description of Yuan Chwang. Therefore it may be concluded that Dignaaga spent the most useful part of his life in Aandhradesa. Tradition says that Manjusree summoned him to develop for the benefit of posterity the “Yogaacaarabhoomi saastra” originally delivered by Maitreya. [1, 87]

As such, while there is every possibility that Dhignaaga was native to Nellore in modern Andhra Pradesh, the state of Odisha too has a claim to him. Nevertheless, his peregrinations were mostly in the Aandhra province, and due to the prominence of Amaraavathi, that is where he made most of his impact.

“Dignaaga largely lived in Aandhradesa and travelled in Mahaaraashtra and Orissa, converting the Tirthikas. In the course of time, he converted a minister of the king of Orissa and founded sixteen Mahaavihaaras. Later, Dignaaga passed away in a forest in Orissa. After his death, his pupils founded schools and carried on the study of his works. Eesvarasena and Sankaraswaamin, the celebrated logicians were the direct pupils of Dignaaga.” [1, 87]

Philosophy

Ancient India, particularly in this period of what is termed “Classical Antiquity”, was deep in the throes of an inter-religious tussle between the Buddhist and Vedic Systems, which then sub-divided into intra-religious tussles between Theravaadha & Mahayaana, etc. The Shaddarsanas or 6 Philosophical Schools of Vedic orthodoxy, also engaged in deep dialectical diatribes internally. And all of these were jointly chastising the Charvakas of yore.

Dhignaaga stands out not only for his adherence to Vasubandhu’s school, but also for his genteel caveats of maintaining decorum in debate and urging an emphasis on the application of knowledge over futile disputation to oblivion (the modern Indian passtime).

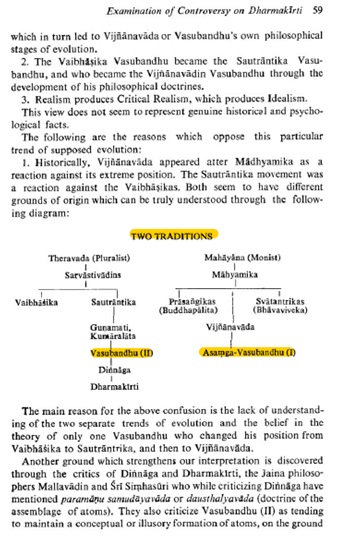

There is some controversy over whether there were 2 Vasubandhus. If so, then Dhignaaga was a follower of the second one who was a Vijnaanavaadhin, from the Sautraantika sub-sect of the Theravaadha Tradition. It is important to note that the Vijnaanavaadha school is also known as Yogachara, credited to Asanga. To ameliorate confusion, here is a framework below.

In brief, like most Bauddhas, he believed that valid knowledge could be determined from two sources (pramaanas), which were pratyaksha (perception) and anumaana (inference). Doctrinally, his philosophy remains a complicated mapping.

“His system shows an admixture of Sautraantika and Vijaanavaada tenets and he is known to have criticized Naiyaayika logical theories. With him therefore begins a new epoch in the history of Buddhist thought and in that of Indian philosophy. Later the Buddhist thinkers began to take an active part in philosophical debates and a keen interest in logical theories.” [1, 88]

Achievements

Acharya Dhignaaga’s achievements are litany. He fittingly commenced his career with a Commentary on Vaadha-vidhaana (‘Method of Debate’). [4, 35]

“According to I-tsing, ‘this star of the first magnitude in logic was the author of 100 treatises.’ The Pramaana Samuccaya is the greatest of his works and it is believed to have been composed near Vengi. It was the earliest work on modern pure Nyaaya which developed Pramaana or evidence as means of knowledge. It was Dignaaga who separated logic from disputation and replaced the word Vaada by Nyaaya. At first he gave expositions to his ideas in a series of short tracts, some of which are preserved in Tibetan and Chinese translation. Later the tracts were condensed into the Pramaana samuccaya in six chapters in verse with the author’s own commentary. Later Jinendra Buddhi composed a good commentary on it called Visaalamalavatee.” [1, 87]

I-Tsing lists 8 works of Dignaaga used by his students as textbooks for logic. Most are fragmentary today:

- Aalambana Pareeksha

- Tirkaala Pareeksha

- Hetucakra damaru

- Nyaayamukha

- Nyaaya Pravesa

But Logic, to Dhignaaga, was only a means to an end. The greater goal after all was Nibbaana (Nirvaana). His contribution to the Sautrantika school, and by extension Theravaadha, cannot be minimised. He was prolific and detailed in his treatment, and was later ably defended by his successor, Dharmakeerthi.

“Besides a number of works on logic, Dignaaga composed Prajnaa Paaramitaa Samgraha or Prajnaa Paaramitaa Pindaartha, in which he expressed his views on the theory of Advaya. Haribhadra quotes his work twice in his Abhisamayaalankaaraloka. Tucci has published the entire work with an English translation. In this Dignaaga says that Pranaapaaramitaa (highest wisdom) is non-dual knowledge and that is the Tathaagata.” [1, 88]

Stcherbatsky says that in Dignaaga “One finds a comprehensive system of critical philosophy.” Some of his works were rendered into Chinese by Paramaartha in the 6th Century A.D. “[1,88]

“Dignaaga is said to have controverted Eesvara Krshna the author of the Saankya Kaarikaa and defeated a Braahmana logician named Sudurjaya in a religious debate. He subjected Vaatsyaayana also to criticism.” [1,88]

Legacy

Dhignaaga’s legacy is difficult to gainsay. Although he did not found Indian Logic (that credit goes to Akshapaadha Gauthama), he did establish himself as “The Father of Buddhist Logic”. His contribution to Indian thought here is undeniable. Irrespective of whether he hailed from Aandhra, Tamil Naadu, or Odisha, he travelled Peninsular India and made his mark throughout.

He was a prolific author and teacher. He was the student of Vasubandhu II, and had numerous students of his own. He delved into the complexities of philosophical thought and existence itself without being an existentialist or a dogmatic. Above all, he stands out as a voice of reason on rationality. Indeed, the qualified disputant must himself be an adherent of the truth; otherwise, he is unqualified.

The modern Indian today has a proclivity to screech ahead to advance courses, while ignoring or neglecting primary lessons and first principles. In the quest to appear the smartest and most knowledgeable, he is frequently the stupidest and most ignorant. He uses the language of Dharma, but means something else all together.

#JaishankarsRuler

— Shivoham (@Ganitamrita) February 25, 2023

Hindus have to grow out of the mindset that their personal problems are Dharma's problems, but Dharma's problems are not their problems. https://t.co/hbsYxdfldf

“To the common people his teachings were only a code of morals intended for self-improvement and for promoting harmonious social life. They were satisfied with them. Such teachings are known as Vyakta upadesa or exoteric teachings which constitute the original or basic teachings of the Buddha. To the highly intellectual persons who could understand deeper things, he taught very intricate [esoteric] subjects and subtle issues of philosophy. ” [1, 2]

That is, in fact, what is lost today. The idea of Dharma as a code of morals and ethics for the common person to guide his or her life is of fundamental importance. Rituals (Nithya Karma) have their role, but the deeper aspects of deep culture are found in norms that preserve justice in society—that is the basis of harmony (a just order, not order for its own sake). Those who misuse birth and privilege for personal gain may make claim to Rta, but practice it not, and they are the enemies of Satya. Truth is the origin of Rta and Dharma alike. And it is Sathya which ascertains the actual role of an individual in society—in every context—so that society is not in turn injured by selfish individuals.

Hindu razor-sharp @ personal/family deals but gullible & naive when it comes to society/community/national dealshttps://t.co/MHvEBbyFng

— Shivoham (@Ganitamrita) September 24, 2017

That is why to receive truth, particularly esoteric (vs exoteric) truth), students (of any age), must first demonstrate fitness for it. If they are still mired in sense addiction and egoistic outrage, and carp and cavil, then not only truth, but even logic is not for them. Indeed, to teach such characterless fools formal logic is to teach a nuisance how to menace society.

“The people with their higher intellectual qualities could go deep into the ontological perception of the Buddha and develop his teachings. These are guhya upadesa or esoteric teachings, which were expounded and elaborated through the writ[i]ings and commentaries of great luminaries like Acarya Naagaarjuna, Aaryadeva, Dignaaga, Bhaavaviveka, Asanga and Dharmakirti over a long period of time. The result was the rise and develop-ment of Mahayaana.” [1, 2]

The Buddha made his division not on the basis of birth but on the basis of character and capacity. This is apparent in the Dhammapada. Each individual’s character and capacity was evaluated before deciding whether he was fit to receive higher knowledge. Those still addicted to the vices of senses or egotistic pride, were denied it until they could demonstrate the virtues of humility and unselfishness (this is what the Buddha meant when he praised the Brahmins of yore, not on the basis of birth, but Brahmins on the basis of demonstrating such ascetic qualities).

“On the other hand, Dignaaga was criticized by the most famous Buddhist thinkers like Chandrakeerti, and by Braahmanists such as Udyotakara, Kumaarilabhatta and Paarthasaaradhi Misra. However this great logician doubted the efficacy of logic in fully grasping the Dharma.” [1,88]

Indeed, logic, whether Vedic or Buddhistic, is only a means to walking the path of Dharma. The final path of Moksha or Nirvaana is attained through perfection of character and contemplation, which are spiritual rather than ritualist-materialistic endeavours. Mastery of logic is merely the starting point.

References:

- Sitaramamma, J. Mahayana BUddhism in Andhradesa. Delhi: Eastern Book Linkers. 2005

- Dhruva, Anandshankar B. The Nyaya Pravesa : Part I. Baroda: Oriental Institute. 1968

- Nariman, C.K. Literary History of Sanskrit Buddhism.Bombay: Indian Book Depot. 1923

- Singh, Amar.Heart of Buddhist Philosophy:Dinnaga and Dharmakirti. New Delhi: Munshiram.1984

- David, T.W.Rhys. Early Buddhism. London: Archibald Constable. 1908

- David, T.W.Rhys. History and Literature of Buddhism. Calcutta: Sushil Gupta Ltd. 1952