A version of this Post was published at Andhra Cultural Portal on September 30, 2014

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s recent speech at the United Nations revived the old debate on “national language”.

In response, conventional media and social media have been alive with debate, some informed, most un-informed. Some object to the very notion of Hindi as national language, seeing it only as 1 of 2 official languages. Others reject it both as national and official. A smaller subset concedes its official status but insists on English or Sanskrit as “national” link language. Nevertheless, all this has yet again provided a moment for introspection. Is Sanskritised Hindi India’s official and national language? Was Shri Narendra Modi correct in using this version of Hindi (any version of Hindi) to represent India? While his previous directives to encourage the use of Hindi across the country initially stirred this pot, the General Assembly appearance (available in the full 35 minute video below) outright churned it.

http://youtu.be/0ZOWBojcOLc

What’s more, it added the additional seasoning of Shuddh Hindi vs Bollywood Bhasha (which has increasing left common Hindustani or even Urdu for outright near Rekhta, as is seemingly in fashion on the other side of Wagah…if that). That’s what makes the opposition of the naysayers so humorous. The same voices who raise a hue and cry about “Northern Imperialism” and “Brahminical conspiracy” have no problem imposing regional or even non-Indian infusions (i.e. English, etc)—hypocrisy in its worst form.

In a particularly telling incident a number of years ago, one buffoon spouted off on how because India was an “IT Choopar pavar” software could be developed to automatically translate orders from an officer to a jawan in his mother tongue. Said moron predictably failed to answer what the contingency would be if an EMP destroyed the translating device—rendering all conversation, let alone orders, unintelligible). And that, folks, is the problem.

For almost 70 years this debate has dragged on to such ridiculous extremes due to self-centeredness on one end, self-entitlement on the other, compounded by stubborn Indian Stupidity and its penchant for argument for the sake of argument. The current clash has virtually divorced the discourse from the fundamental premise of Hindi as Official and National language to begin with. So let us start with the basics:

Article 343 of the Indian Constitution specifically stipulates the following:

“(1) The official language of the Union shall be Hindi in Devanagari script”

“(2) Notwithstanding anything in clause (1), for a period of fifteen years from the commencement of this Constitution, the English language shall continue to be used for all the official purposes of the Union for which it was being used immediately before such commencement:

Provided that the President may, during the said period, by order authorize the use of the Hindi language in addition to the English language and of the Devanagari form of numerals in addition to the international form of Indian numerals for any of the official purposes of the Union”

…

Article 344. Commission and Committee of Parliament on official language

…

(2) It shall be the duty of the Commission to make recommendations to the President as to—

(a) the progressive use of the Hindi language for the official purposes of the Union;

(b) restrictions on the use of the English language for all or any of the official purposes of the Union”

…

Article 351. Directive for development of the Hindi language.—“It shall be the duty of the Union to promote the spread of the Hindi language…by drawing, wherever necessary or desirable, for its vocabulary, primarily on Sanskrit and secondarily on other languages” [emphasis mine]

As such, for all the whiners, hysterical drama-bazis, and whirling dervishes of outrage, the fact remains what the Prime Minister did, and has been doing, perfectly comports with the intent and the letter of the Constitution: Hindi drawing primarily from Sanskrit is the official language for the Union, and should be used to represent India internationally. In fact, rather than repeatedly copying and pasting the [strategically amended] preamble (which even a child can do), perhaps the naysayers should start reading the actual articles of the Constitution (especially A.44).

Concerns about Regional identity vs National identity

There have long been concerns about regional identity vs national identity. To what extent should regional culture be patronised without compromising unifying factors. In short, how to avoid the dangers of new Periyars and Bhindranwales, while at the same time ensuring preservation of and justifiable pride in regional identity?

On the other end, we have those who point to the bifurcation of old Andhra Pradesh state as evidence of the obsolescence of linguistic states and even regional identity itself. Unitary system advocates posit that Federalism itself is problematic, and speak in terms of 1 dimensional nationalism. But along with the Constitution (which is Federal in Structure; Unitary in Spirit) the Mahabharata itself gainsays this when it states:

“Tyajet ekam Kulasyarthe, Gramasyarthe Kulam tyajet; Gramam Janapadasyarthe, Atmarthe prithivim tyajet”

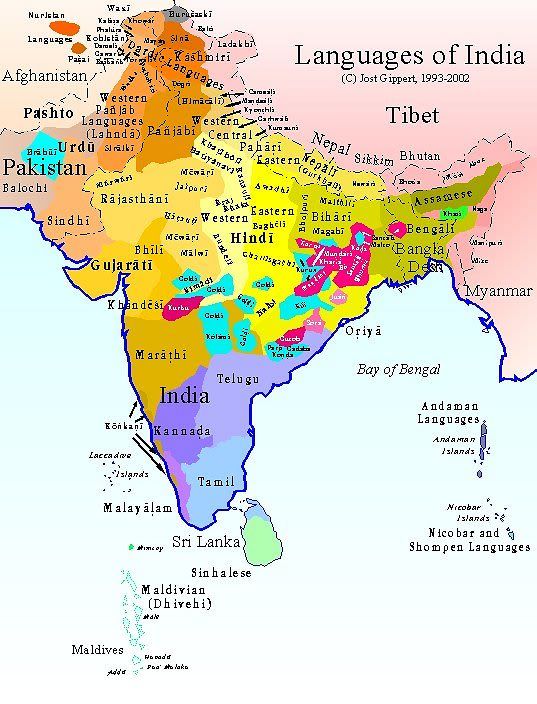

Thus, we all owe duties to our family, region (i.e. villages), and country (desh being above the rest in this ascending order). The entire business about citing Hindi’s pedigree versus more ancient Kannada or Tamil is preposterous. By that token, what is English’s pedigree compared to Hindi?–do the research on the origin of Angrez then talk (while you’re at it, ask the French what they think of English).

Dharma is our common thread, and Sanskrit the high language of its expression and culture. Hindi serves as a common tongue and is already used within the army by enlisted soldiers–it is the language of the jawan. Many of the same regionalists whining about Hindi would have no problem imposing their own regional language on others.

The language of government should be accessible to both the cultured grandee and the common man. Despite my love of Sanskrit, it is in recognition of this reality that I, as a proud Telugu, support Hindi as the national language, for the following reasons:

Reasons for Hindi

- De Jure Basis

- De Facto Basis

- Historical analogue to Prakrit

- National Pride

Basis for Opposition

- Hindi Hegemony (implies others less Indian)

- Regional languages threatened

- Native languages antiquated, English is Global, Modern

Rebuttal of Opposition

- Revive regional dialects of Hindi, many of which can be their own languages.

- Even without Hindi, regional languages already threatened…by English

- The most advanced/modern countries in the world use their own native languages

Reasons for Hindi

De Jure Basis

While we already touched on the substantive text of the Constitution establishing Hindi as the official language of India, it is quite clear time and again that the intent of the framers was for Hindi to be the national language as well. Article 351 clearly demonstrates how they desired to spread not English, or Farsi, or Abyssinian, or Esperanto, but Hindi throughout India. While the directive principles clearly establish the recognition of 22 Official languages of India, thereby preserving and sustaining the right of regional linguistic and cultural expression, the language of national dialogue and global representation of the nation was intended to be Hindi.

When that noble scholar in the English language (and Chairman of the Constitutional Drafting Committee), Shri Ambedkar, posited Sanskrit as the official language (demonstrating its validity to Indians across class and caste), it was ultimately Nehru, that Anglicised doyen of the left, who steered the official language to Hindi. Even Chakravarti Rajagopalacari a.k.a. Rajaji initially supported Hindi, despite being a Tamilian (and before TN politics later forced him to backtrack). No less than Gandhiji posited Hindi as the national language, yet his alleged inheritors on the left act as though English is somehow the Gandhian choice–it’s not, he chose Hindi. He pointed out that there are five requirements for a national language:

“‘(1) It should be easy to learn for government officials.

(2) It should be capable of serving as a medium of religious, economic, and political intercourse throughout India.

(3) It should be the speech of the majority of the inhabitants of India.

(4) It should be easy to learn for the whole country.

(5) In choosing this language considerations of temporary or passing interests should not count’.

English, Gandhi declared, did not satisfy any of these requirements, and he had no hesitation in declaring that Hindi satisfied all of them“.

De Facto Basis

Like it or not, two institutions have made Hindi use widespread. The first and most important is the Indian Army. While traveling in Chennai, I as a Telugu was faced with a conundrum when in need of information. Out of habit, I began my question in English. The very Tamilian jawan on duty said, and I quote, “no Angrez, only Tamil or Hindi”. I’m not going to lie, I felt a surge of post-colonial pride.

A similar occurrence took place when I was in Delhi. It so happened for whatever reason my relative’s housekeeper was a Tamilian, who didn’t speak much Telugu. Again, what language did two South Indians from different states and different socio-economic strata rely on for communication?—Hindi. Granted, this had less (really nothing) to do with the Army and more to do with location, it again demonstrated that I as a Telugu was no more inclined towards Tamil than I was to Hindi, despite the former’s geographic proximity (and vice versa).

The second and unofficial institution is Bollywood, which has also served to popularise Hindi to the extent that it’s actually become identified as the National Film Industry. The top talent from South and East gravitate to Hindi cinema for precisely this reason. Hema Malini, Rekha, Sridevi, and Aishwarya all cut their teeth in regional film before eventually going “national”. Indeed, one need only take a look at Telugu cinema’s actresses to see how Tollywood became a minor league of sorts for aspiring Bollywood stars.

But relying on Bollywood alone will not serve the cause of ensuring Hindi’s status as the national language, since “Hindi” cinema has also been in danger of drifting from the constitutional directive. An (North) Indian-American writer recently said as much:

The movie’s stilted dialogue in Persianized Urdu to evoke the Mogul era was as incomprehensible to my Indian aunt and uncle, who live in Gurgaon and speak fluent Hindi, as it was to me

Thus, it becomes all the more imperative to reorient Bollywood and our Cinema in general back to Sanskritic culture. As the incisive Christopher Hitchens once said, “Globalization is only really interesting if we all bring something different”. Rather than encouraging films catering to others in the name of “Being global”, we should focus on reviving the cultural essence of India.

Historical analog to Prakrit

With rare exception, Prakrit was the typical language of administration in Ancient India. Even the Satavahanas of Andhra and the Pallavas of Tamil Nadu used it for governance. The very meaning of the word Sanskrit is “refined”, whereas the word Prakrit means “normal or vernacular”. As there were many Prakrits (i.e. Ardh-Magadhi, Maharashtri, etc) so too are there many “Hindis” (Garhwali, Bhojpuri, Avadhi). Even the Pali of Ashoka Maurya is considered part of the Prakrit family. The fact that distant Southern empires of Ancient India used Prakrit is only further evidence that Hindi too can be accepted as a language of national administration and international representation.

Let me further clarify by saying that I firmly believe the language of state administration should be the regional one and that resident students must learn the state language. State Assemblies should conduct business in the native regional language, whether it be Assamese, Gujarati, or Kannada, but let the language of Rashtrapati Bhavan and Sansad Bhavan indeed be Hindi. “Adhyaksha Mahoday(a)“.

National Pride

There is something really shameful about an ancient civilization that respectively boasts quite possibly the most refined and ancient language, the 4th most common language, and what I as an Andhraite will insist is the sweetest language, yet we rely on a parvenu patois of an undistinguished Germanic dialect heavily infused with Latin and Viking French for our national communication. Don’t get me wrong, I certainly do not caucus with the luddites who want to kick out English, computers, and anything else that prevents them from handing out jobs to their cronies/party workers, but there is a such a thing as national and civilizational pride.

Geopolitically and commercially, English does have value to India (and it can be taught alongside our own as part of the 3-language formula), but language is also culture. For the same reason we at ACP advocate to revive the linguistic culture of the people of Undivided Andhra, so too should India revive the national culture of its civilization through a native language.

Having established the fundamental premises for (re)-establishing Hindi as the national language, let us then examine and deconstruct the specific prongs of opposition to it.

Basis for Opposition

1. Hindi Hegemony (implies others less Indian)

This has been a common complaint for Indians hailing from South of the Vindhyas. Many resent the idea of Hindi as both official and national language because they feel it devalues and even disparages their own idiom. Languages such as Kannada and Tamil are hundreds (or depending on how we define Hindi) even thousands of years older, with rich pedigrees and classical status to boot. Tamil claims descent from Lord Shiva himself via Maharishi Agasthya, and Kannada was the language of dynasties such as the Rashtrakutas and Chalukyas that crossed the Vindhyas and ruled lands as far Nepal and Bengal.

This sentiment is frequently coupled with resentment at the assorted Madrasi/Northeastern jokes that many non-Hindiwallahs are frequently subjected to. While many do give back as good as they get, I certainly did, they internalised and congealed this feeling into stereotyping all Northerners and retaining resentment (which I did not). Thus, language to many of them has become a way of frustrating what they see as the “over-bearing behaviour of superiority complex-ed Northerners” all while using their linguistic/cultural/imperial pedigrees to construct their own.

Finally, there is the irritating reality that there are many Northerners who do come to cities like Bangalore and Chennai, and don’t learn the local languages…and refuse to. They hope to coast by on English or even put the onus on the local for learning Hindi. This has resulted in (justifiable) movements like No more “Kannada Baralla”

2. Regional languages threatened

There are of course the regional language champions. They complain that the flood of Hindi in schools, government, and movies means their own languages will die out. In the name of defending their regional identity, some Manipuri militants have even “banned Hindi movies”–resulting in the growing popularity of Korean movies and K-Pop (is this going to help either national integration or regional identity?).

Then there is the opportunist. The self-starting, up from the boot-straps or clipped St.Stephens graduate who likes his English advantage with his single-malt Scotch, and will be damned if some “vernie” seeks to undercut his hard-earned or “inherited” privilege. Thus he posits English as the “link language” for fair play, much like his patrons from John Company once did.

3. Native languages antiquated, English is Global, Modern

This is the latest fashion for the anti-Shuddh Hindi /pro-Hinglish types. Many of these people even take pride in not knowing how to speak their own native regional language, let alone write it. For them, English is the only language of literacy, modernity, and fashionability…becharas. To be frank, I’ve never quite understood what goes on in the minds of these curious characters. But then why analyse what had already been spelled out as explicit colonial policy for subjects of Indian blood…

Rebuttal of Opposition

1. Revive regional dialects of Hindi, many of which can be their own languages

When there are many dialects of Hindi, many of which could be treated as their own language, how is this Hindi hegemony?

When there are many dialects of Hindi, many of which could be treated as their own language, how is this Hindi hegemony?

Bhojpuri’s vibrant cinema is already emblematic of this need for intra-Hindi cultural expression and diversity. Many speakers of Hindi dialects other than Hindustani/Kauravi often find it difficult to adjust to it, prefer their own enough to have a unique film industry, and have their own cultural heritages (Braj, Bundelkhand, Marwar, Mewar) that deserve to be celebrated rather than subsumed. Subsuming is” Synthetic unity”, we need “Integral unity”.

I agree, there shouldn’t only be one “authentic” Indian identity. Being a native of the Hindi heartland shouldn’t automatically designate one as more Indian. But, the same people who idolise China don’t know Mandarin is merely one language of many, and only the prestige dialect of Mandarin (Putonghua) is the official language–with recognised “regional languages”.

“In the early 1900s a program for the unification of the national language, which is based on Mandarin, was launched; this resulted in Modern Standard Chinese”. Much like Hindi, Mandarin holds native sway in a gigantic part of China. But even it is divided into various dialects, which are not always mutually intelligible. In fact, it is only the “prestige dialect” around the national capital region of Beijing that is used for Government, so why do these self-same China admirers in India balk at the use of the “prestige dialect” of Hindi (Kauravi/Hindustani) being used given its origin from around India’s national capital region. These are presumably the same people who went around saying “China’s Chairman is our Chairman”—or are intellectually (or genetically) descended from them.

2. Even without uniform Hindi use regional languages already threatened…by English

Aside from threatening regional languages with obsolescence in modern Indian homes, English may also serve to shut the less fortunate out. Many of our self-styled saviours of regional language posit how English is a better choice, because it puts everyone at an equal disadvantage (Indian crab mentality doing its work) and prevents Hindi from drowning out “vernaculars”. However, as if on cue, a recent article discussed how “India’s media, English-educated elites, and its government have often seemed out of touch with the majority of India’s population.”

It goes on to note that “The problem with this is that it is logistically impossible for all Indians to learn English well enough to use it in this manner, which limits its learners to those who are either good at learning languages or to those who grow up in an environment that exposes them to it from birth so that they pick it up easily. Hundreds of millions of Indians who are otherwise hardworking or talented but poor or not good with languages often do not get the opportunities in life that they deserve simply because they do not know English.”

As the article concludes, Hindi is far more closely related to Gujarati, Marathi, Odia, and Bengali than English is, not only making it more accessible, but shielding these languages in the process. Presumably, the primary complaint comes from the South, but there again the prescience of India’s constitutional framers becomes clear as Hindi primarily drawing from Sanskrit was specifically stipulated–putting Hindi again closely in the grasp of Telugu and Malayalam, which draw over 80% from Sanskrit, and followed not too distantly by Kannada. Tamil is the only outlier, and by some estimates it too is around 30-40% influenced by the Pan-India classical language. Sanskrit vocabulary therefore forms the only significant repository common to India’s large, native languages, and preserves them in the process. Whereas English simultaneously becomes a threat to the professional prospects of less fortunate regional language speakers all while extinguishing the regional language itself in upper and increasingly middle class homes.

I also want to know what exactly these self-styled saviours have done for their own languages? It seems regional languages are only a tool to oppose Hindi/National integration rather than a principle put into practice. Other than sarcasm (in actuality petty poseur passive-aggressiveness garbed in affectation), these champions of parochialism go back to general uselessness when the dust of debate settles. For all the talk of “English exploding in India”, ” It should be noted that English is spoken or understood by about 150 million Indians, or about 10 percent of the population. This means that around 90 percent of Indians do not understand or speak English.” So only around 10 percent know varying degrees of English, but more than 41% speak Hindi as a first language. Non-native speakers of Hindi would easily give this existing plurality a majority.

Thus it’s clear India’s elite and upwardly mobile only want to preserve their inherited English advantage or at best oppose because they “don’t want to give undue status to Hindi”. Yes, better for all to be equally enslaved than to have 1 first among equals–sounds vaguely familiar… Once again, it’s quite apparent these hypocrites are speaking only in their self-interest. The question is, who will speak out in the national interest?

Interestingly, this question of preserving native languages is not only an Indian one. In fact, the French themselves have long resisted the invasion of English. Once the language of culture and diplomacy of the European elite, la langue Francaise has been relegated to a global has-been, with only spheres of influence in parts of Africa and former colonial enclaves elsewhere (i.e. Pondicherry).

In their commitment to preserving the cultural validity and modern relevance of their language, the French have gone to the extent of not only insisting on translating Anglicisms such as “email”, but even attempting to anticipate popular words of science and business in order to translate them in advance. How easily we Indians give up what the French hold dear. Language is culture.

Looks like Rajnath Singh was right after all.

Even those Chinese learning English don’t replace their own with it, only add to an existing quiver of languages.

The key is forming academies to ensure India’s languages keep pace with science and sociology. But establishing such academies seems to be too much work for our sepoys, who insist “only English will allow for debelopment”.

As a recent article discussed,

“of the top 20 richest countries in the world per capita, only four are English-medium based. 16 of the 20 richest have higher education, science, engineering, medicine, business, law all available in their own non-English languages. None of these 20 countries have a disconnect between the mother tongue of their people and the languages of higher education and government. None of these have an English-medium based class system where English is a marker of social and economic standing above the ‘natives’.”

Thus, rather than destroying class, English obsession is reinforcing it.

What is often posited as a regional pride issue is really an individual pride issue. The most vocal voices against Hindi speak not out of concern for the son of the street side hawker, but, as usual, for his own selfish interest. Either his English gives him an advantage, rather than the par or disadvantage that Hindi would, or he is yet another example of the crab mentality of Indians (I would rather see all of us go down, than one of us go up!!!)

As the original article notes, “The division of Indian languages simply for “literary value” and English for professional fields was also an Orientalist prejudice, mentioned in the Macaulay Minute. ” Indeed, “Indian languages are far more scientific than English. Their grammar is more structured, they are phonetic; their alphabet is based on a systemisation of sound. If Japanese and Chinese with their multi-thousand letter writing systems can be used for modern knowledge, there is no reason that Indian languages cannot.”

In sum, whether considering the ancient or modern, classical or scientific, we should remember the following dictum:

“All major civilisations promote their own languages. “

Having laid out the case for Hindi as the official and the national language, what advice do I, as a Southerner, have for Northerners on what they can do to facilitate Hindi’s national use?

What can native Hindi speakers do to help

I recognise there are many well-meaning and even open-minded North Indians willing to learn a Southern or Eastern Indian language in the interest of national integration. For every boorish mohalla-Delhiwallah who throws his linguistic weight around in Bangalore or Mumbai (often with tragic results…), there are many more who are happy to learn beyond Bollywood stereotypes and “idli/vada/sambar”. So I am not here to perpetuate stereotypes, rather, I want to provide solutions. So what can native Hindi speakers do?

1. As previously stated, revitalise your native Hindi dialect’s cultural & literary canon

From the Prithviraj Raso to the Ramcharitmanas, there is an extensive literary canon for the various dialects of Hindi. It is incumbent upon the speakers of these dialects of Hindi to revitalise them. They deserve their due spotlight. North India is more than just Delhi-Agra-Jaipur. It is high time for the sons of Chittorgarh, Pithoragarh, and Pataliputra to take pride in not only historic, but also cultural and linguistic heritages. Your poetry and literature also counts. So take an interest in recovering it and passing it on to the next generation.

2. Ditch the Madrasi/Northeastern jokes

We all know the jokes, “Kallu this/Ch**ki that”, but nothing serves to more reinforce the resistance to Hindi than the “other”ising of your fellow Indian. Coming from Andhra (a region famous for comedians from Tenali Ramakrishna to Hindi film’s Johnny Lever) I am all for good-natured ribbing and witty one-liners. But brainless name-calling and lazy stereotypes are not wit, and making common cause with Pakistanis who, despite sharing the same background as most NI Punjabis, call all Indians “kallu” is the height of stupidity. If you want a united India, act like it.

I also know that with the development primarily in the South (though Gujarat and Gurgaon are actually ahead in some ways), the shoe of late has frequently been on the other foot. Many of our brothers from UP and Bihar have been at the receiving end of unprovoked mockery. So I am not saying don’t defend yourself, just be smart about it. An IT/Visa joke about a “Gult”= fair game. But attacking darker skinned Southerners and epicanthic fold bearing Northeasterners for their looks is crass and cultureless. What’s more, many of them have identified vulnerabilities in the North (all too crass and offensive to be repeated here), so rather than devolve to mutual acrimony and hate-fests, respect others and respect yourself by behaving like gentlemen and ladies–and your fellow Indians will do the same. If they don’t, report them to people like me, and we’ll give them a talking to.

3. Most importantly: Learn the language & culture of the state you live in

It doesn’t matter whether you like the sound of your own mother tongue more (who doesn’t?–though as a Telugu I will axiomatically beg to differ with you), or don’t have a knack for learning new languages; make an effort and pick it up. Trust me, the goodwill you generate from even showing the slightest interest in the local regional tongue will be met with a flood of reciprocation. By not just referring to everyone from Dakshin Bharat as Madrasi or South Indian and taking the time to learn the difference between Telugu and Tamil (or Mizo and Khasi for that matter), you will do more for national integration than all the twitter fights could ever hope to accomplish.

I, as a South Indian, have stuck my neck out for Hindi at the risk of considerably displeasing many of my brethren in Andhra and other parts of India, in the name not of self-interest, but national and civilizational interest. How are you, mere bhaiyon aur behinon of Uttar Bharat, willing to reciprocate in the same national and civilizational interest?

Conclusion

Ultimately, I personally am fine with either Hindi or Sanskrit. Many of late have been vehement in their insistence that Sanskrit and Sanskrit alone fits the bill as national language, and possibly even official language. Others more recently have proposed Hindi as the First Official Language but Sanskrit as the National Language. This suggestion, in fact has more merit, and is worthy of further study, as it allows government accessible to and conversation for the common man, while rooting national thought in the only true Pan-Indian language. However, this invariably calls for a reevaluation of the criteria for and the nature of a National Language (mandatory), and favours its replacement with a Civilizational Language (something available to all, but not mandatory).

I certainly believe Sanskrit is our common civilizational language of high culture, and along with Tamil, one of our two living classical languages, but show me how you’ll get the lance naik of the Indian army or the average auto wallah to learn the language speedily (i.e 1-5 years), then talk. Anybody can form an opinion, but the proof of the pudding is in the eating, so show how you would do it (not in a 140 character tweet, but a 14 or 140 page plan).

I don’t mean just making the case for Sanskrit, but providing the specific plans, timelines, and infrastructure to deliver the end result leading to Sanskrit as national language or official language. Otherwise, it’s quite clear that certainly in the near and even medium term, Hindi (as defined by the Constitution) alone fits the bill, and Sanskrit will remain a civilizational fountain. Pragmatism must also drive our decision and there is a need to organise ourselves correctly AND swiftly to meet the challenges of the future.

I mean for God’s sake, we are surrounded by hostile foreigners plotting to take our land and even our loved ones, but 70 years later we are still bickering over what language we should use for national communication?!!! Are we understanding the gravity of the situation? ARE WE A SERIOUS PEOPLE?!!!

The Bottom line is this: it has been almost 7 decades since India attained Independence. Whatever side you’re on, this debate is now beyond stale, and the “imposition” charges without merit. “Vell, VEE NEED CONSENSUS FIRST”, bray our gyaanis—well gyaani, there is such a thing as a reasonable time limit for consensus, and cloture for debate—and thanks to your dilly-dallying, the time is now up. Whether top-down or bottom-up, people, it’s time to make a call…what’s the national language?—as far as the Constitution is concerned, the matter is already settled…

References

- Constitution of India

- http://thediplomat.com/2014/07/why-india-must-move-beyond-english/

- http://thediplomat.com/2014/07/language-and-basic-rights-in-india-beyond-english/

- http://www.niticentral.com/2014/06/28/revitalising-indian-languages-will-unlock-our-civilisational-genius-232436.html

- http://rajivmalhotra.com/library/articles/response-postmodernist-charge-essentialism/

- Planet India. New York: Simon&Schuster. 2007. p.98

- http://www.openthemagazine.com/article/art-culture/a-historical-sense

- http://www.rediff.com/news/slide-show/slide-show-1-indias-english-obsession-must-end/20140626.htm

- Dasgupta, Jyotirindra. Language Conflict and National Development: Group Politics and National. p.110

- http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/361585/Mandarin-language

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/8820304/Frances-Academie-francaise-battles-to-protect-language-from-English.html

- http://www.academia.edu/7602522/The_Ability_of_Sanskrit_to_Coin_New_Words

- Rao, P.R. History and Culture of Andhra Pradesh. Delhi: Sterling. 1994

![[Reprint Post] Culture: The Cure for Stupidity](https://indicportal.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/3085064-Wendell-Pierce-Quote-The-role-of-culture-is-that-it-s-the-form-150x150.jpg)

![[Reprint Post] On the Importance of History](https://indicportal.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/george-santayana-history-quotes-those-who-do-not-remember-the-past-150x150.jpg)