Indic Decision Making Under Uncertainty—3: What Would Arjuna Do?

Background

Part—2 identified two divergent western streams of decision making and examined their strengths and limitations that are briefly summarized below:

Memoryless (prediction-free) decisions based on tacit doing or ‘convex’ tinkering contextually harness uncertainty to become locally robust or locally antifragile to unseen contexts. We presented examples of how real-world tinkering can come with large hidden or ignored consequences instead of the small errors of a convex world. On the other hand, history-centric (data driven, e.g., based on AI predictions) decision-makers aim to conquer uncertainty and automate decisions for a future that is expected to closely resemble the past. This can be disastrous when confronted with unforeseen contexts. Those who forget history or bank on history are both condemned. An equally serious issue common to both approaches is that ethics and fairness are not built-in to the decision-making process and must be externally imposed. Is there a way out of this deadlock?

This third installment studies Indic decision-making by learning from the choices made by our ancestors during pivotal events in the Mahabharata.

[all emphases within the quotes used in this post are mine].An Indic View of Uncertainty

One is struck by the lack of anxiety in the Nasadiya Sukta of the Rg Veda when it talks about the uncertain origins of the world. Since ancient times, India has sought to understand the connections between the original transcendent forms (typifying order or negentropy here) and their myriad worldly manifestations (reflecting increasing uncertainty or entropy) through Vedic Yajna [5, 7]. Similarly, Hindu teachings differentiate between Shruti, the Vedas that are apaurusheya and timeless, and a multitude of Smritis, which are man-made texts to be remembered and updated. Shruti and Smriti are not disparate but an integrally united [7] twoness whose teachings have been transmitted by living gurus across generations. Smritis guide decision-making in the presence of the real-world constraints that arise in a specific context, in order to maximally uphold the universal ethics of Shruti. Such an approach neither forgets nor banks on memory. Notably, Karma, which plays a fundamental role here, does not find a place in the brief history of western decision making [3].

Decisiveness in a Sea of Uncertainty

To keep things interesting, let’s turn to the tale of Raja Chandrasen (Caṇḍasiṃha, king of Tāmraliptī) and his loyal assistant Sattvasheel (Sattvaśīla). This is the seventh story of the Vetālapañcaviṃśati (Baital Pachisi) series in the Kathasarithasagara [1].

“.. King Trivikramasena went back to the śiṃśapā tree, and again found the Vetāla there, and took him on his shoulder. As he was going along with him, the Vetāla said to him on the way: “King, listen to me. I will tell you a story to make you forget your fatigue …”.

In the entertaining story that follows, the assistant is instructed by Raja Chandrasen to proceed on a challenging sea-faring mission. Mid-way through the journey, their ship is besieged by mysterious asuric forces and starts to flounder. To keep the king’s mission alive, Sattvasheel immediately plunges into the sea with his sword in hand to take on this unknown threat even as the ship sinks. There he enters a mysterious and wondrous world of asuras that was ruled, most unexpectedly, by a beautiful lady (the daughter of Kalanemi) who worshiped Mother Durga. Transfixed by her visage, he is seemingly tricked by the clever princess and unwittingly teleports himself back to Raja Chandrasen’s palace garden through a water tank that turned out to be a ‘wormhole’.

In a state of utter bewilderment and angst, Sattvasheel narrates this strange story to his king. The brave and compassionate Chandrasen instantly grasps his friend’s predicament. The king, who already owed a debt of gratitude to Sattvasheel, vows to discharge that debt by reuniting him with the sea-princess, come what may. He hands over all administrative duties to his ministers and accompanies Sattvasheel to the same location in the sea where the ship sank. They dive underwater and enter the underworld of asuras. Through his wise and kingly words and actions, Chandrasen finds a way to repay his debt to Sattvasheel and restore harmony between the two kingdoms. The Vetala’s question is simple:

““Now tell me: which of those two showed most courage in plunging into the water?”

When the Vetāla put this question to the king, the latter, fearing to be cursed, thus answered him:

“I consider Sattvaśīla the braver man of the two, for he plunged into the sea without knowing the real state of the case and without any hope; but the king knew what the circumstances were when he plunged in, and had something to look forward to, and he did not fall in love with the Asura princess, because he thought no longing would win her.”

When the Vetāla received this answer from the king, who thereby broke silence, he left his shoulder, as before, and fled to his place on the śiṃśapā tree. And the king, as before, followed him quickly to bring him back again; for the wise never flag in an enterprise which they have begun until it is finished.”.

The ‘fractal’ context-within-a-context format is often employed in Indic traditions. The outer story is the Baital Pachisi (Pachisi is also a famous board-game of chance that originated in ancient India). As the story ending indicates, the brave and wise Emperor Vikramaditya (King Trivikramasena) is stuck in a loop of bringing down an elusive Vetala from the tree and listening to his story that comes with a question. He is compelled by the Vetala’s rules of the game to speak when he has total clarity about his answer: “Tell me, for you are the chief of sages. And if, King, you do not tell me the truth, though you know it, this head of yours shall certainly split in a hundred pieces.” [1]. King Vikram invariably gives the right answer, allowing the Vetala to slip away, and the process resets. Their mutual path to liberation from this cycle starts with the certain and the expressible, but must ultimately pass through silence. This path finally opens up when King Vikram is given a paradoxical problem whose answer is entangled and inexpressible: “When the king heard this question of the Vetāla’s, he turned the matter over and over again in his mind, but he could not find out, so he went on his way in silence.” [1]. These stories were part of Indian folklore many centuries before Wittgenstein.

"What can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence.

” - Ludwig Wittgenstein's key statement in Tractatus Logico-philosophicus.

In this seventh iteration of the Baital Pachisi, King Vikram rightly chose the assistant for his decisive and selfless actions in the midst of extreme uncertainty and chaos whereas Raja Chandrasen had a pretty good idea about what to expect and what he needed to do. Uncertainty is recognized as the pramana for courage here for there can be no real heroes in a scripted Bollywood world.

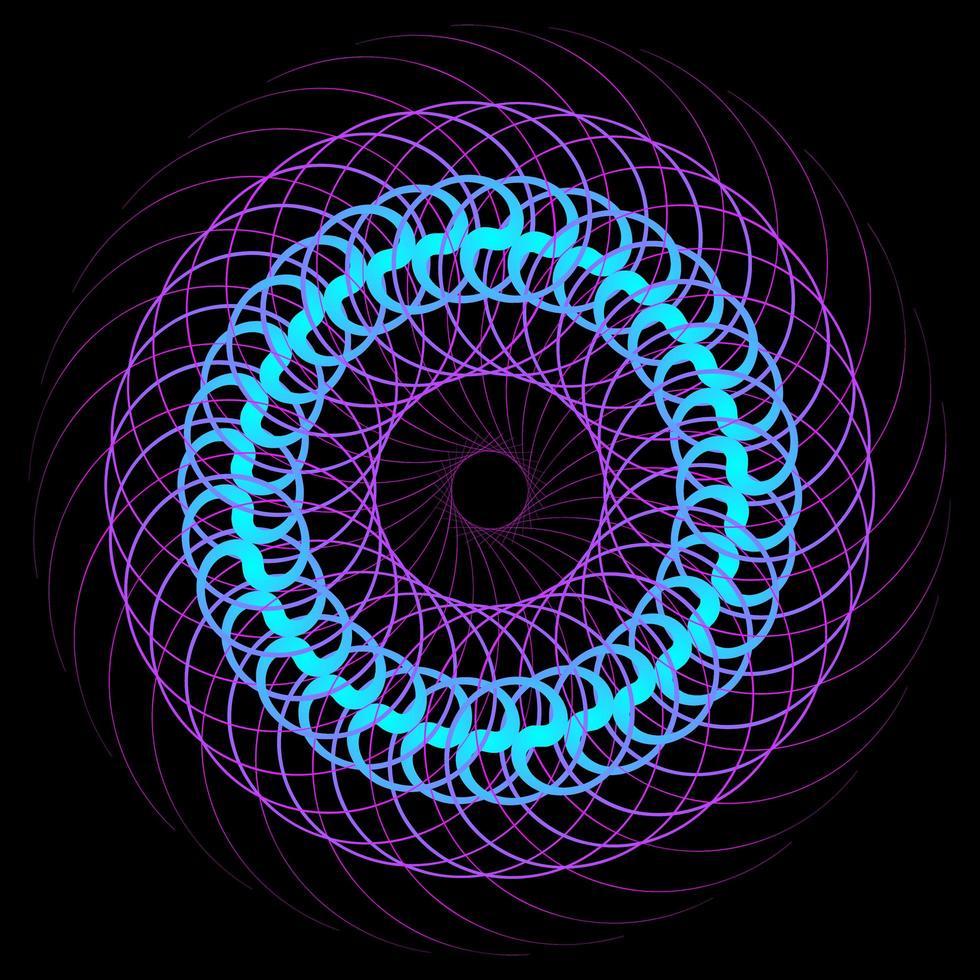

To summarize, we can either pursue our purusharthas and accept the consequences per our karma. Alternatively, one can choose antifragility as the way ‘to live in a world we don’t understand’ and harness uncertainty to either gain or limit losses. The third option of AI/internet data driven decision making is widely marketed as the ‘future’ of decision making. While tacit doing and AI are not devoid of plus points, there is no need to guess which path the Bhagavad Gita recommends. Whenever we think of the Gita, we remember Sri Krishna; but being mere mortals, we can also never forget Arjuna, the instrument of the divine decision maker. Hindu commentators have recommended that before making key decisions we ask, “what would Sri Rama do?” and “what would Sri Krishna do?”. Both are valid suggestions but in this Kaliyuga, the yuga characterized by maximal uncertainty, it is also important to ask: “what would Arjuna do?”

Kaliyuga: Era of Extreme Ambiguity

Mahabharata Game of Dice. Printed by Chore Bagan Art Studio, Public Domain, Link

Our Itihasa and Puranas describe episodes where the protagonists make decisions while subject to extreme stress, which clearly reveal their priorities; the decisions made by our ancestors at critical times repeatedly re-energized an entire civilization even as the rest of the ancient world slowly fell apart. Sri Rama who decides to obey his father and accept fourteen uncertain years in the wilderness. Sri Krishna who fully grasps the spiraling consequences of adharma’s antifragility (gaining from every crisis), which is emphatically demonstrated during the diabolical game-of-dice (similar to Pachisi). Rajiv Malhotra’s discussion in ‘Being Different’ [7] underlines the central role of karma and uncertainty here:

“Dice is also used as a metaphor for uncertainty in the Mahabharata… Yudhishthira, the otherwise righteous king, is addicted to dice play, and this is portrayed as a catastrophic vice. The dice game is nevertheless an obligatory and significant part of the Vedic ritual of royal consecration (‘rajasuya’). The four ages (yugas) of successive decline are named after the four faces of the Indian dice (with the unlucky face, Kali, corresponding to our own chaotic time). The king’s throw of the dice during this solemn ceremony suggests not only the uncertainty at the heart of cosmic order but also the power of the human ruler to determine his own yuga”.

Many wise and righteous elders present at that disastrous event were paralyzed by the collective failure of their decision-making process that had become mechanically history-centric and ossified. On the other hand, Shakuni, the master of the dice, and his nephews abandoned dharma, which allowed them to exploit such indecisiveness to gain from disorder at the expense of the Pandavas and eventually dragged Bhaaratavarsha into the Kurukshetra war. We know how it ended.

What would Arjuna do?

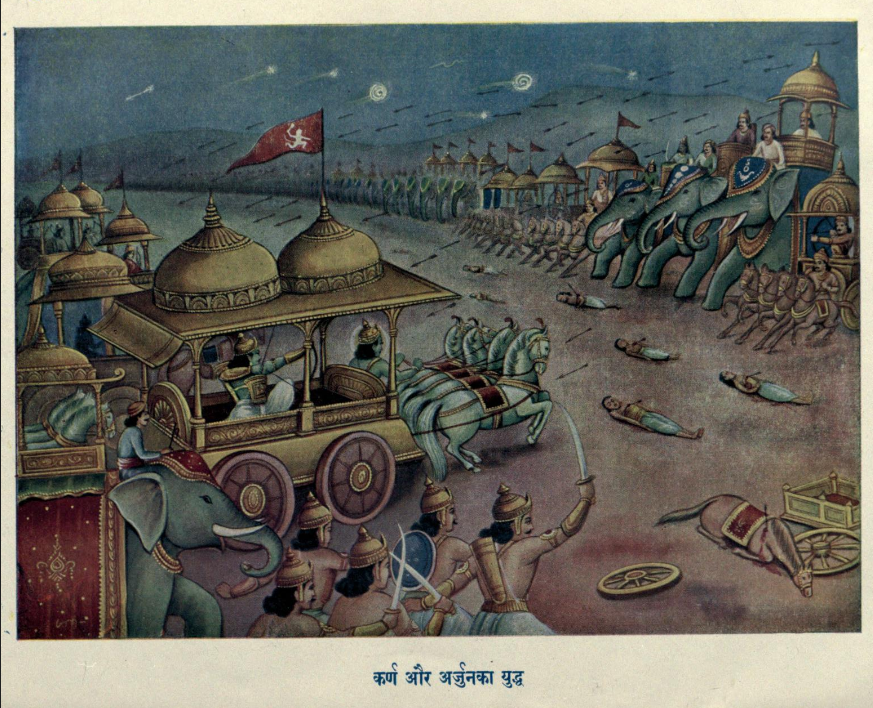

The Mahabharata presents a fascinating comparison of the choices made by Arjuna and his bitter arch-rival and elder brother Karna as part of their battle preparations. The latter’s lifelong quest for offensive military capabilities and gladiatorial glory in single combat against Arjuna ended with the exchange of his robust, unbreachable armor for a fragile single-use super-weapon. A humble Arjuna, the master practitioner of archery whose arrows hit targets from a distance with the highest predictability did the opposite by spurning Yadukula Krishna’s powerful but fragile armies. He only sought the divine decision-making guidance of Parthasarathi so that he may never aim at the wrong target and never shy away from vanquishing adharma.

By Ramanarayanadatta Shastri. Gita Press. Public Domain, Link

This choice by Arjuna proved to be pivotal to the fortunes of India and the world. The universal relevance of dharma civilization’s decision-making process to this day is evident in these excerpts from an essay by Dr Antonio De Nicholas [4]:

“.. the West will realize that both Plato and Pythagoras are footnotes to the earlier cultures of India, as in the Katha Upanishad, Rg Veda etc. Indic texts had already marked the individual training and ethics of social life. Nothing short of excellence will do. The training for excellence is to practice the embodied technologies of decision-making, the right decisions, the wise decisions, when needed by the present dharma, context, one faces. This is the goal, the ethics of the whole program of the Avatara Krisna in the Bhagavad Gita: to train Arjuna, that fallen and disturbed warrior, to make decisions, the best ones, as needed by his present dharma (his present situation), a battlefield. And this is the program of human acting, from the Rig Veda down, that Indic texts propose: an ethics of decision making as opposed to an ethics of compliance to rules coming from the outside.”.

There is no doubt that India is the original home of ethical decision making. AI seeks to outsource decisions to automatons. Western religion teaches subservience to a rigid book that decides for us. Dharma traditions alone train us to be self-organized and identify a dharma-optimal choice, including contexts that we have never encountered before. Kaliyuga will frequently throw up entirely new contexts. Dr Antonio De Nicholas continues:

“.. Decision-making is a must-ethics in a world that is so ambiguous… Arjuna in the Gita collapses in the first chapter unable to make the decision to fight in a very ambiguous -to him-situation. Family, friends, are on both sides of the battle field. Krsna takes him on a journey of communities and acts (yogas) he was familiar with for ten chapters until his whole organism opens and is able to see (chapter eleven) the geometries on which the passage and dissolution of nama-rupa ,names and forms, takes place. This is the embodiment of the Avatara in its full manifestation. A man has been able to embody in one lifetime the technologies of the present culture to the point of having it constantly present so that when called upon he may make the best decision, from among the possible, for the benefit of all…” [4]

Hindi Gita Press. Vishwaroopam. By B.K. Mitra, Public Domain, Link

The Gitopadesam is not an after-the-event postdictive excursion. Neither is it a pre-war prophecy of guaranteed hellfire to “unbelievers” and eternal life to “believers”. Even after the Gitopadesam, Sri Krishna does not predict Arjuna’s future. Arjuna as a military leader and warrior must make longer-term as well as real-time decisions while dealing with all the uncertainty of life, death, and everything in between.

Past data is of limited use. This is an entirely new context that pushed Arjuna to the brink of cognitive implosion. The Gitopadesam is given to us at a civilizational inflection point where every decision comes loaded with extraordinarily far-reaching and cascading consequences. The future of our adhyatmic civilization rested on the battlefield decisions of the noble Arjuna under the guidance of Sri Krishna. Dr Antonio De Nicholas continues:

“.. in the end the subject, Arjuna, may by habit decide from the desires of his heart whatever he wants: yatha icchasi tatha kuru (now that you know do as you wish).”

“…Indic Classical texts had already imprinted in the species the ability to practice “virtue by habit”, i.e., the ability to make decisions in ambiguous situations. And it is these technologies that need to be revived again now that the ambiguity of the world is so pronounced…”. [4].

हतो वा प्राप्स्यसि स्वर्गं जित्वा वा भोक्ष्यसे महीम्।

तस्मादुत्तिष्ठ कौन्तेय युद्धाय कृतनिश्चयः।। –Bhagavad Gita 2.37.

Yet, there is a possibility that Arjuna may have fought the war bravely like a gladiator and prevailed in the Kurukshetra war without the Yoga of the Bhagavad Gita. To many an external observer, Arjuna’s battles would’ve appeared just as courageous. After all, a most influential modern treatise on decision-making [2] celebrates gladiators as role models. What would have been the state of such a post-Kurukshetra Kaliyuga Bhaarata?

To better answer this question, we can first study the intent behind the widely followed dharmic practice of Ekadashi Vratam. This representative example helps establish an Indic pattern of decision making that has been embodied and transmitted in India over millennia.

Ekadashi Vratam versus Intermittent Fasting

Modern Western studies found that the human body can be antifragile to intermittent fasting. Prof. Taleb dives deep into this topic in his book [2]. Of course, what is not mentioned here is that such ‘findings’ about the human body response to perturbations were known and at a far deeper level in Ayurveda. We will get more into this in later episodes of this series.

Ekadashi Vrata are followed on certain dates of the Hindu luni-solar calendar. Swadeshi author, aerospace engineer, and Bharatanatyam instructor Smt. Prakruti Prativadi remarked on twitter about Ekadashi Vratam.

Upon request, the author was kind enough to provide details on the intent of a Vratam [8] that are paraphrased and excerpted below (any errors in transcription below are mine):

Vrata has been used in several contexts and finds mention in Shruti, Smritis, and Bhagavad Gita, among other sacred dharmic works and: “Vrata is also mentioned in Patanjali’s Mahabhashya – “vriyate iti anena” meaning one chooses to abide by that mode of conduct and is thus part of Yama and Niyama.

Vrata has no direct root but is a product of other root words.

.. there is a common truth and principle in the different usages of Vrata as it appears in the Veda-s and samskara-s – to discipline oneself and adhere to a way whether in food and/or conduct or way of life such that it purifies the inner and outer self. Vrata is not a rite or ritual and not transactional (“I will get some reward if I do this vrata)”.

Shraddha is another Sanskrit nontranslatable of Hindu dharma. In India, we always hear elders chide the half-hearted efforts of kids, saying: “whatever you do, do it with Shraddha”. The book on Sanskrit Non-translatables [6] explains:

“The word shraddha etymologically derives from a combination of two words, srat and dha. Srat is a Vedic term for truth (sat) and dha means ‘to hold’ or ‘to nourish’; shraddha thus means ‘to hold or align your mind with the truth or reality’. Shraddha in its original and primary sense denotes feelings of reverence towards the divine or a spiritually evolved being;

…Shraddha purifies the antahkarana and augments the efficacy of sadhana.”

To a casual observer, a ‘scientific’ person practicing intermittent fasting to get stronger, and a Bhakta during an Ekadashi upavasa may superficially appear to be doing the same thing, but their cause and intent dramatically differ, and the lifetime result and the path beyond is also different. In the former case, the reward-seeking intent as well as the outcome both strengthen the ‘doer ego’ whereas a Vrata is never performed with a self-serving objective but with Shraddha and as part of a lifelong Saadhana to unite with the divine. What is also interesting is that such dharmic practices naturally come with health benefits.

‘Convex’ tinkering can produce personal laabh (gain) but only a dharmic approach yields shubh laabh (~ auspicious gain) that is truly sustainable. Ancient India appreciated Chanakyan antifragile investment and planning methods (see Part-1) but understood it well enough to not put it on a pedestal and make it an ideal. Arguably, the author of that Arthasastra himself realized the karmic implications and limitations. An idea of ‘celebrating the Gladiator who takes the fall for us and keeps the system antifragile’ imitates the well-known Abrahamic ‘savior’ model [4] that rejects Karma. Missing in the useful but limited idea of skin-in-the-game is Karma, the ultimate skin in the game.

"Karma is not a matter of God playing dice or arbitrarily assigning fate, nor is it random, nor the result of some primal collective sin. Contrary to its frequent misappropriation in the West, the karma theory is really a guide to good action and not merely a model that explains present circumstances. As the consequences of one's karma play out, the karma gets erased, but the record gets replenished with fresh karma since the ego is always making choices." - Rajiv Malhotra [7].Such profound concepts are easily internalized by Bhaaratiya kids from an early age through play, e.g., the traditional dharmic board game of Moksha Paatam (lesson). This game was digested into ‘snakes and ladders’ after deleting Moksha and Karma and replacing it with an Abrahamic model of sin, redemption, and randomness.

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Nomu420 CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

From a Ganita perspective, ‘Ahimsa Paramo Dharma’ in the Mahabharata represents the dharmic decision optimization principle of minimum harm. This principle can be practically applied in engineering projects to optimize decision variables in the system to find a least-harm solution (see this ICP series on Indic Engineering [9]). Thanks to such wisdom, traditional India made wise investments that minimizes not only their carbon footprint but also Karmic footprint and remains the world’s oldest continually lived civilization.

We can summarize this post through a study of Arjuna’s intent.

Arjuna’s intent

At Sri Krishna’s lotus feet, Partha personifies Indic decision making based on adhyatma vidya, a dharmic embodied knowing [7] rather than the ‘tacit doing’ of the West. While both involve a certain kind of inexpressible ‘doing’ in the real world, the latter is mere karma. Such actions produce gain at the expense of an increase in the doer’s fragile ego as well as himsa as it lacks the yoga of the Bhagavad Gita.

Sri Velukkudi Krishnan explains on twitter: “Sri Krishna advised Arjuna to fight as that is his dharma. That is Karma yoga which would lead to Bhakti yoga and ultimately Mukti. Hesitant Arjuna wanted to get away to forest and practise Jnana yoga. Krishna said “Duryodhan, Karna would make fun and ridicule you as a coward.. Becoming furious you would return to battle field and fight. But Arjuna, note that, if you fight for the cause as I told, that is karma yoga but if you fight as you wish, that is just Karma. Decide”. Same action but results differ in line with cause. (Bhayat ranat uparatam …)”.

सुखदुःखे समे कृत्वा लाभालाभौ जयाजयौ।

ततो युद्धाय युज्यस्व नैवं पापमवाप्स्यसि।। –Bhagavad Gita 2.38.

There is a gigantic difference in the long-term consequences of Nishkama Karma and mere Karma of tacit doing. An entire civilization and its treasury of sustainable practices have been bequeathed to us by Rishis who realized the divergent impact of seemingly negligible differences in intent. Governments are better off investing in #DharmaForChildren to build a nation of self-organized Arjunas as opposed to raising a mass of Duryodhanas that outsources critical decisions to predictive machines or optionality driven Shakunis. In today’s highly uncertain and interconnected world of cause and effect, the world’s leaders in every sphere of human activity would surely make far better decisions for this planet if only they internalized the Bhagavad Gita and asked themselves before acting: what would Arjuna do?

Arjuna and Karna battle. By Ramanarayanadatta Shastri. Gita Press. Public Domain, Link.

References:

- Kathasaritsagara Book 12. https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/kathasaritsagara-the-ocean-of-story. Compilation attributed to Somadeva, 11th Century CE.

- Nassim N. Taleb. Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder. Kindle Edition. Random House. 2012.

- Leigh Buchanan and Andrew O’Connell. A Brief History of Decision Making. Harvard Business Review (Magazine). 2006.

- Antonio T. de Nicolas. The Avatara and The Savior: The Philosophical Foundations of Politics. Infinityfoundation.com. Original Presentation circa 1986.

- Prakruti Prativadi. The Bharatanāṭyaṃ Yajña. Third Swadeshi Indology Conference. Chennai. 2017.

- Rajiv Malhotra and Satyanarayana Dasa Babaji. Sanskrit Non-Translatables: The Importance of Sanskritizing English. Amaryllis. 2020.

- Rajiv Malhotra. Being Different: An Indian Challenge to Western Universalism. Harper Collins. 2011.

- Prakruti Prativadi. Vrata. Private Communication. 2021.

- Indic Civilizational Portal. Integral Engineering in the Sulba Sutras -3. 2018.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the ICP editor for his valuable feedback, and to Smt. Prakruti Prativadi for the enlightening pointers, especially regarding Ekadashi Vratam.