Introduction

Part-1 reviewed the modern concepts of local fragility, robustness, and antifragility (FRA) [3] in the context of decision making under uncertainty. A study of Kautilya’s Arthasastra (1500 BCE per Pauranic Chronology or 300 BCE) reveals a clear understanding and application of FRA principles in sync with dharma and purusharthas that finds application within modern decision support systems. Bharata’s Itihasa and ancient texts long before Kautilya contain deeper decision-making principles that transcend FRA.

This second part is a search for that deeper, more persistent civilizational wisdom that protects and guides us in an AI-automated, uncertain world. This leads us to the following questions:

what is the outcome of building AI whose decision-making under uncertainty follow western models?

Would the outcome be different if AI were primarily guided by dharma?

The first question leads us through a sequence of binaries that have fragmented western decision making and are presented below. We study the dharmic alternative in the final installment.

[all emphases in quotes are by this author]

Binaries that Fragment Decision Making

We will start with excerpts on the hidden costs of automation from Mike Cooley’s 1990 essay on AI and Culture [2]:

"..we begin to regard design as that which reduces or eliminates uncertainty; and since human judgement, as distinct from calculation, is itself held to constitute an uncertainty, it follows from some kind of Jesuitical logic that good design is about eliminating human judgement and intuition.

..attempts to produce workerless factories have revealed that such highly synchronized systems are incredibly vulnerable.. Systems will be more robust and capable of withstanding uncertainties and disturbances if there are skilled workers who understand the system and can anticipate and regulate difficulties..

.."In systems terms, both the culture and the competence transmitted [through apprenticeships] embodies wide levels of "systems redundancy". That is to say, the skilled person had ranges of competence, knowledge and skill which far transcended the individual tasks on which they were engaged".

From the machine-augmented human intelligence of the industrial revolution to human augmented AI of the 20th century to this century’s quest for commoditized complex AI, it appears that mechanization has increased fragility—the exact opposite of the envisioned master plan for a robust AI. So why are we following this trajectory?

The Tacit and the Explicit

The 1950s, hidden between WW2 and the chaotic 60s, were quietly eventful. Wittgenstein, whose research into the inexpressible and whose philosophy of mathematics and language are actively studied today, passed away in 1951. Alan Turing, who pushed the boundaries of what is expressible and computable, devised the Turing Machine and proposed the Turing Test for AI, departed the world in 1954. A sharp difference in perspectives between the two is evident from their interactions in Cambridge [15]. The second half of the decade yielded new ideas for both sides. The Perceptron algorithm was invented by Rosenblatt four years later in 1958 paving the way for explicit machine-generated predictions by artificial neural networks (ANNs). 1958 was also the year that Michael Polanyi‘s book drew western attention to the importance of personal and tacit knowledge (TK) in decision making.

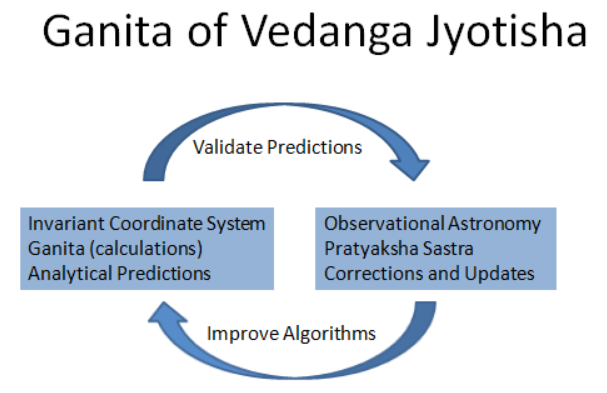

Since the 1950s, TK and mathematics has been synthetically united within the data-driven world of empirical models based on statistical inference and machine learning (ML). The data used to calibrate such models represent a distilled curation of past outcomes of tacit human decisions plus their contexts. Note that the final goal is usually not the prediction (“x”) but decisions based on the prediction, i.e., some f(x). Today, 80-90% of AI/ML business applications rely on human skill from development to post-deployment. Such TK-AI are engineering feats closer to the Indic tradition of Ganita based on Pramana rather than the infallible proof-driven Euclidean Mathematics.

It comes as no surprise that TK and AI began drifting apart in a quest for a “pure AI” untainted by human touch, much like the Euclidean-Jesuit “pure math”. It is a fond hope that such ANN-automated technologies will soon be able to deeply understand the interconnected world to attain a level of expressibility where lives can be bet on their recommendations.

It comes as no surprise that TK and AI began drifting apart in a quest for a “pure AI” untainted by human touch, much like the Euclidean-Jesuit “pure math”. It is a fond hope that such ANN-automated technologies will soon be able to deeply understand the interconnected world to attain a level of expressibility where lives can be bet on their recommendations.

Autonomous AI’s modes of fragility

Hands-free AI decisions work well inside a lab-like stationary world but are fragile outside. For example, the remarkable Go playing AI trains itself to invincibility by playing, winning, and losing within the same box a zillion times [5]. The real world allows but a few tries; a single LPHC (low-probability high-cost) shock can reduce us to toast anytime; game over. Not surprisingly, only toasters come guaranteed.

Hands-free AI decisions work well inside a lab-like stationary world but are fragile outside. For example, the remarkable Go playing AI trains itself to invincibility by playing, winning, and losing within the same box a zillion times [5]. The real world allows but a few tries; a single LPHC (low-probability high-cost) shock can reduce us to toast anytime; game over. Not surprisingly, only toasters come guaranteed.

Unlike stylized math, these models and algorithms do not come with provable guarantees but work remarkably well in benign settings having repeatable patterns [5] or where the cost of a bad decision is limited. While this theoretical NP-Completeness (“x”) is not in and of itself a practical issue, the consequences f(x) manifest within interactive AI settings, rendering them fragile to user-experience. They are inefficient and fragile with respect to data quantity and quality. An overwhelming majority of business users distrust such opaqueness and fragility. Consequently, AI has failed to take off in several flagship applications [4, 5] even as news media oversell AI prophecy and drive up future expectations.

"In a truly open-world problem devoid of rigid rules and reams of perfect historical data, AI has been disastrous.

Moravec’s paradox: machines and humans frequently have opposite strengths and weaknesses." - David Epstein in 'Range'[6].

This “Look ma, no hands” design reflects a Jesuitical notion of order and certainty by eliminating the chaos and uncertainty (and value) of TK from the loop. Like a potent new drug with hidden side effects, commoditized AI is cheaper upfront because it transfers all latent fragility to the user. The durability of products match the attention span of the customer.

An alternative approach to decision making under uncertainty discussed in part-1 is the Kautilya Arthasastra approach that examines outcomes and exposure to achieve a degree of robustness or even antifragility. This approach involves TK, which is indeed about ‘doing’ and breaks away from reductive Aristotelian models [3]. However, an approach that does not prioritize dharma offers only local antifragility at the expense of a more global fragility. This example shows how randomized tinkering led a ‘doer’ from Morphine to Heroin and subsequently slipped into women’s and children’s medicines. We can only apply ethical band-aids to contain such harm. Keeping this limitation in mind, let us study TK.

Decision Making Driven by Tacit Knowledge

An easy way to appreciate the tacit is through playing and taking part in sports. Test Cricket is a good example of TK-driven decision-making (see this) in a domain known for its “glorious uncertainties“. Classical batting (think Rahul Dravid) is about:

a) Understanding path dependence: a robust defense to ‘survive, then thrive’

b) Eliminating the bad and finding good scoring options

Successful batsmen appear to have ‘figured out’ entirely by doing, the best combination of a) and b) that works for them in any given match context. This naturally leads to the bifocal antifragile playbook of Kautilya’s Arthasastra (!) that pays dividends in sport: combining rock-solid defense with selective, profitable offense. Sporting theory is easy; the magic is in the ‘doing’. Sportspersons express the inexpressible better than philosophers*:

"Forecasting is very difficult, especially when it involves the future. In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is. How can you think and hit at the same time?" -Popularized by 'Yogi' Berra, NY Yankees.

(*excluding Suzuki Subramanyam who said you’d miss the magic in a quest for logic!)

The next section studies this western dichotomy of antifragile ‘doing’ versus fragile ‘naive rationalizing’ based on the discussion in ‘Antifragile’ [3].

Doers vs Model Builders

Artificial intelligence (AI), and the cognitivist view of mind on which it is based, represent the last stage of the rationalist tradition in philosophy." - Hubert L. Dreyfus [8].

‘Rebooting AI’ [4] offers a sound critique of what is wrong with AI. Whether their theory of fixing AI’s robustness problem is realistic is not so clear: “Building robust cognitive systems has to start with building systems with a deep understanding of the world, deeper than statistics alone can provide ..”.

Prof. Taleb has discussed the limits to deep understanding [3]. His view is that we live in an increasingly fragile planet in which the media “induce an illusion of understanding the world“. He is emphatic about our cognitive limit:

“randomness in the Black Swan domain is intractable. I will repeat it till I get hoarse. The limit is mathematical, period, and there is no way around it on this planet.

.. The mission is how to domesticate, even dominate, even conquer, the unseen, the opaque, and the inexplicable.”

We find two opposing western approaches here [3]:

Type M: Top-down theorizing using reductive models built on reasoning, naive rationalizing, and on top of past models. Hindering reality is ignored. Such academic ‘provable’ models are suitable for “know what” narrative building.

European scientists as late as the 1930s theorized that insects (not just bumblebees) couldn’t fly. Disobedient bumblebees debunk such ‘science’ by simply doing their dharma.

AI decisions are also driven by reductive models directly abstracted from terabytes of historical data. Such training data are reductive by design as they primarily consist of happenings, not non-happenings or stuff deemed irrelevant. Note the asymmetry: excluded facts can cause longer-term harm than fake data and the resulting problems like racial bias and Hinduphobia are likely to increase. Big data does not solve this problem. It can accelerate harm by greatly increasing spurious correlations: “in large data sets, large deviations are vastly more attributable to noise (or variance) than to information (or signal).” [3].

Some AI models are useful, all are fragile. Handle with care.

Type D: The tacit and largely inexpressible way of doing- tweaking and refining by in-the-trenches practitioners and algorizers. They “know how”. To do is to work with uncertainty and get through LPHC shocks.

The roots of this tension between the model builder and chaotic doer lie in the deep schism in the west between Hellenic reasoning and Hebraic dogma after Aristotelian rationalizing was synthesized into Christianity by St Thomas Aquinas [1]. Table-13 of ‘Antifragile’ [3] lists: Abrahamic dogma -“in the religious sense, the unexplainable” and myth as helpful to doers; their counterparts kerygma –“the explainable and teachable part of religion” and logic lend themselves to a theorizing, narrative building Type-M. ‘Antifragile’ can also be viewed as a math-backed push-back of the Orthodox Christian Hebraic ‘doer’ against the Hellenic ‘theorizer’ within the western big tent.

Key observation of this study: Western AI and decision making is both driven and divided by its Hebraic-Hellenic synthetic unity. This union collapses when it faces uncertain consequences that can only be managed through inner transformation. This fragile, history-centric AI is bound in the thrall of future expectation whereas TK in its Yogic self-aware form resides in the present.

Viewed through an Indian lens, the Sci-Fi classic Nightfall by Isaac Asimov offers a vivid example of this problem. A sustainable solution exists in the large dharmasphere that even the UN forgets.

Ganita vs Mathematics

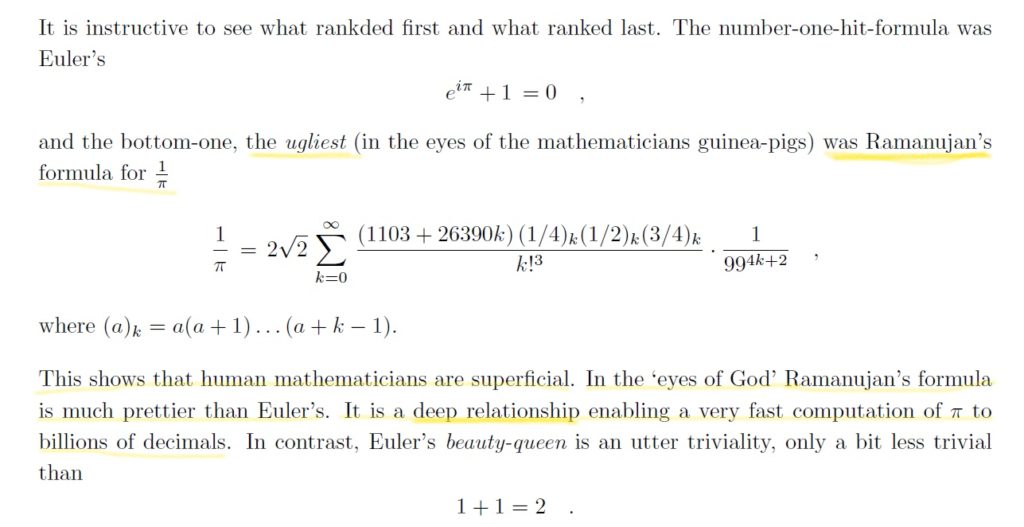

Using an Indian lens, Swadeshi scholars have noted the fallibility of Euclidean mathematics and differentiated it from Ganita. To learn more about model building versus Indian algorizing, the reader is referred to Prof. Roddam Narasimha [19]. An ICP Ganita series has summarized these findings and contributed its bit to this effort. This fault line has prompted mathematicians [6] to emphasize ‘doing’ and turn Mathematics into a science—a move that would take it closer its Ganitasastra roots:

“Beware of Greeks Carrying Mathematical Gifts: Once upon a time, a long time ago, mathematics was indeed a true science, and its practitioners devised methods for solving practical mathematical problems. The ancient Chinese, Indian, and Babylonian mathematicians were dedicated good scientists. Then came a major set-back, the Greeks!

..Western Philosophy, with its many pseudo-questions was developed in the hands of Plato, Aristotle, and their buddies, and `Modern’ pure mathematics was inaugurated in the hands of the gang of Euclid et. al.”

An applied versus the pure mathematician’s ranking of the ‘most and least beautiful’ equation among more than a dozen famous choices [7] embodies this divide:

The Hindu way of learning and knowing since times immemorial is through Prayoga. Key Ganita non-translatables here include Yukti, Upapatti, Pramana. The ancient Vedic people developed a Ganitasastra that transcends M/D binaries.

For example, sulba constructions and demonstrations are 'self-verifying'. No separate theorem is necessary. Hindu idea of prayoga: Doing is both learning and knowing.

— Shivoham (@Ganitamrita) February 11, 2018

Yet Indian pedagogy has adopted Mathematics and forgotten its Ganita that even western scholars are trying to bring back.

Prof. Taleb reconstructs the ‘doer’s history’ of Europe and remarks that their famous builders (e.g., Romans) were doers who: “relied on heuristics, empirical methods, and tools, and almost nobody knew any mathematics—according to the medieval science historian Guy Beaujouan, before the thirteenth century no more than five persons in the whole of Europe knew how to perform a division.” Barely a century later, Madhavan Empranthri arrived at a calculus without limits in India. Yet the combined Hebraic-Hellenic narrative sold to the world is that in four centuries they moved from division to inventing calculus. Ganita has been simply airbrushed out of historical data. ‘Antifragile’ attributes major inventions of the Industrial revolution to a spurt of European ‘uninhibited doers’ who turn out to be clergymen with lots of spare time. Curious. While the doer’s history in the west gets upgraded, let us see how Indian history has been treated by western scholars.

Swadeshi vs Western Indology

Western Indology prefers academic theorizing adding layer upon layer of reductive modeling rather than direct, immersive learning through dharmic practices. A good example is the Harvard-schooled Indologist Sheldon Pollock:

a) He postulates a practice-driven innovative culture for the west ignoring its M-D problem while

b) simultaneously denouncing Indian lived traditions and Sastras as top-down static texts that kill innovation, arriving at this result using top-down Type-M academic theorizing.

Western Indologists mistake what is opaque and unintelligible to them as incoherent and unintelligent [3]. Swadeshi scholars have explained how Shastras are radically different from the western idea of scriptures [1, 9]. They do not suffer from M-D tension of the west. Yet western academicians continue to assert their “dissertations and book chapters” as Adhikara over disobedient Hindu Bumblebees. In AI-speak, this layered Western Indology should be termed Deep Racism to differentiate it from the unsupervised ‘Race Science‘ classifiers of their equally worthy ancestors. They used calipers to measure our nose and head dimensions and used this training data to criminally divide and grade us into hierarchical ‘castes’ and ‘wild tribes’. Contrast this with a critique emerging from immersive experience: the scholarship of the 14th CE Tamil commentator Nachinarkkiniyar [10].

We may wonder how dogma is conducive to the western way of doing. Admitting a limit to deep understanding (based on history-centric religion or pure math) opens the door to a TK-driven quest for antifragility and longevity. This ego-driven doing transfers fragility elsewhere. This pattern can be seen in the last section of this post that summarizes the TK of different philosopher-doers cited in [3] who contributed to FRA ideas.

Philosopher-doers from different Western schools of Thought

"..the reliance on historical and prophetic revelation ties humans to the past while the lure of salvation keeps them fixated on the future, resulting in dissonance in the present moment." - Rajiv Malhotra in 'Being Different' [1].

Seneca the Younger of Rome (4 BCE – 65 CE)

Seneca the Younger was a Stoic. Prof. Taleb considers this stoicism as “pure robustness— for the attainment of a state of immunity from one’s external circumstances, good or bad, and an absence of fragility to decisions made by fate, is robustness“.

The discussion does not move inward from external robustness into the fragility of individual ego [1] and remains in a material realm with duality intact.

Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali (1058 – 1111 CE)

Prof. Taleb recognizes al-Ghazali as a skeptic fideist noting [3] “historically, skepticism has been mostly skepticism of expert knowledge rather than skepticism about abstract entities like God…“. Indeed, Al-Ghazali’s religious belief was absolute and his skepticism was reserved for ‘Type-M’ scholars like Ibn-Rushd:

“Al-Ghazâlî’s critique of twenty positions of falsafa in his Incoherence of the Philosophers (Tahâfut al-falâsifa) is a significant landmark in the history of philosophy as it advances the nominalist critique of Aristotelian science..

“In his own ethics al-Ghazâlî stresses that the Prophet—and no other teacher—should be the one person a Muslim emulates.” – [11].

Prof. Taleb records Ibn Rushd’s adverse impact on western thought [3]: “it is not Aristotle whom Aquinas is quoting— he calls him the Philosopher— but the Arab synthesizer of Aristotle’s thinking, Ibn Rushd, also known as Averroes, whom Aquinas calls the Commentator. And the Commentator has caused a great deal of damage. For Western thought is vastly more Arabian than is recognized..“. [12].

After getting the better of many opponents in debate, Al-Ghazali’s quest led him to the Sufis and their methods digested from dharma practices. His eloquence could not dent their TK and Al-Ghazali retreated for years into an ascetic inner search: “..And this is where; he finds refuge, or answers in Sufism, and their claim of their particular “ state,” meaning mysticism.

..a person becomes absent from his senses and withdraws into himself. It is a state that the individual witnesses on his own and realize as a country that is free from the principles of the intellect.” [12].

Al-Ghazali’s search led him to a “crisis that penetrated his existence, and affected his health eventually.” [12]. The inner quest terminated with duality and inner fragility intact. He adopted and prescribed a Sufi lifestyle to ‘discipline the soul’ so one can emulate the one prophet and no one else. He also issued a fatwa [11]. This dogmatic end is representative of the irresistible influence imposed by history-centrism on western tacit knowledge and decision-making.

Ernest Renan (1823 – 1892 CE)

Renan was an orientalist who learned from Hindu texts and is known for his views on an Indian origin of Christian concepts [14]. He too was firmly rooted in Judeo-Christian history-centrism. His quote cited in ‘Antifragile’ is important to the tussle between the Aristotelian logician vs the DIY practitioner:

“In his attack on Averroes [Ibn Rushd], he expressed the famous idea that logic excludes— by definition— nuances, and since truth resides exclusively in the nuances, it is “a useless instrument for finding Truth in the moral and political sciences.” [3]

A recent use of this quote can be found in ‘Pigeon Tunnel’, the 2016 autobiographical work of the influential British novelist John Le Carré who passed away a few days ago.

The perfectly expressible path is also the surest way to a dead end. Dharma traditions were always aware that intellect and deductive logic can play a supporting role but are not the primary means of reaching the Truth (see this discussion). India offers a radically different approach to understanding the nuances that attracted all these western seekers.

Unfortunately, the irresistible Aristotelian urge to reject the embodied knowing of dharma and embrace the expressible ‘know what’ has overtaken Indian intellectuals. As Prof. Taleb remarks [3]: “..the most severe mistake made in life is to mistake the unintelligible for the unintelligent— something Nietzsche figured out.. mistaking what we don’t see for the nonexistent, a sibling to mistaking absence of evidence for evidence of absence..”.

Nietzsche‘s philosophy was influenced by Indian thought [1].

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951 CE)

Born wealthy and of Jewish ancestry, he started his career as a mechanical engineer and was a decorated soldier in WW1. Wittgenstein’s importance in the west has steadily risen. There are similarities in his writings with Indian thought [17]. Wittgenstein was a seeker initially influenced by Schopenhauer who had learned from Indian texts. He did interact with Indian scholars and knew something about dharma traditions [18]. Like Al-Ghazali, Wittgenstein started from the textual and expressive and converged to the tacit and ‘mystic’ opaque.

“Language is a labyrinth of paths. You approach from one side and know your way about; you approach the same place from another side and no longer know your way about. ..There are, indeed, things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest. They are what is mystical. ..He must so to speak throw away the ladder, after he has climbed up on it. ..Thence we pass successively to Theory of Knowledge, Principles of Physics, Ethics, and finally the Mystical.. "'You think you are very clever, Shah, you think you know more than these [Jain] ancestors of yours who have thought about these things for thousands of years?'.." -Wittgenstein.

An ancient Tamil word for Vedas is ‘Marai‘, i.e., the veiled/secret (Rahasya). The renowned Vedanta work Vivekachudamani is cited by Rajiv Malhotra [1]: “‘shabdajaalam maharanyam chitta bhramana kaaranam’ (the net of words is a great forest that causes confusion). Shastras (spiritual texts) provide useful pointers to the spiritual seeker, but must eventually be transcended lest they become a trap in their own way“. Wittgenstein’s ‘throw away the ladder’ has also been compared to Buddha’s ‘discarding the raft’.

Wittgenstein’s arguments about the way we perceive reality has implications for AI and underscore the need to preserve Sanskrit nontranslatables and Indic languages “.. our language determines our view of reality, because we see things through it. So he no longer believed it to be possible to deduce the pre-existing structure of reality from the premise that all languages have a certain common structure.” [13]. About this duckrabbit picture: “..we can also see the illustration now as one thing now as another. — So we interpret it, and see it as we interpret it.“.

A deeper, seamless transcendental perspective can be found within the cow-elephant depictions in our ancient Hindu sculptures and paintings.

Superb old painting. When you look at Vishnu, he'll be riding elephant. If you pay attention to Siva, elephant becomes Nandi! pic.twitter.com/hNOPBzXDf4

— Aviator Anil Chopra (@Chopsyturvey) September 25, 2017

@subhash_kak darasuram temple near kumbakonam TN 12 th century . Cow or elephant ?! pic.twitter.com/CFjMulxTwc

— Patriotic Ganesh 🇮🇳 (@ganesh_kala59) May 3, 2020

Wittgenstein’s ideas fall short of integral unity. He was rooted in a Judeo-Christian duality that was “100% Hebraic” and free of Hellenistic adulteration [16]. While acknowledging that Wittgenstein’s notions have some similarities with Indian thought, Rajiv Malhotra is prescient about the final result:

“Postmodern thought in the West has gone to great lengths to deconstruct normative categories, but in the absence of the notion of purna (or Brahman), the end-result, as I have said elsewhere, is narcissistic and nihilistic, or leaves a vacuum that is eventually appropriated into some normative framework..”

From TK to Embodied Knowing

TK lacks the embodied knowing techniques of dharma civilization [1], the ultimate antifragile. FRA-related books study TK in the context of external systems such as nations, evolution, healthcare, AI, etc. A big gap in this western worldview is that our inner fragility manifests in our external decisions, priorities, and systems we choose to build.

Our actions directly depend upon our thoughts. The nature and quality of our actions are clear amplifications of the nature of our thoughts.⠀#swamichinmayananda⠀#Chinmayam⠀#wordsofwisdom⠀#reflections#vedanta #morningwisdom pic.twitter.com/kRzvltjYLe

— Swami Chinmayananda (@Chinmayananda) November 30, 2020

Western seekers identify sensory limits and accept them as an absolute dead-end. Rajiv Malhotra [1] points out that western thought “has failed to develop a repertoire of techniques and practices to overcome these limits. In the Bible, God imposes limits on human knowing as symbolized by the divine injunction not to eat from the tree of knowledge of good and evil. Modern Western secular frameworks in science and philosophy also often claim limits to the mind in a variety of disciplines. The West developed no systematic science comparable to adhyatma-vidya in overcoming these limitations“.

The western approach to decision making is governed by ethics derived from the Judeo-Christian ‘golden rule’ [3]. This rule proposes a local compromise and ‘tolerance’ between individual egos. Radically different from this is the dharmic golden rule [1]. Where western philosophy and tacit knowledge ends, Vedanta darshana and embodied knowing of dharma begins.

[to be concluded].

Acknowledgments & Disclaimer Thanks to the ICP editor for reviewing this work. This is a Ganita practitioner's perspective drawn directly from decades of 'in-the-trenches' experience including mission-critical engineering. Opinions expressed here are personal. The critique presented is not a denial of the hard-fought progress achieved by many dedicated AI engineers, researchers, and organizations. This post is our small shraddhanjali to Sri Roddam Narasimha (1933-2020). Om Shanti.

References and Further Reading:

- Rajiv Malhotra. Being Different: An Indian Challenge to Western Universalism. Harper Collins. 2011.

- Mike Cooley. The New Technology and the New Training: Reflections on the Past and Prospects for the Future. Chapter in ‘Artificial Intelligence, Culture and Language: On Education and Work: Editors: Bo Göranzon and Magnus Florin. Springer Verlag. 1990.

- Nassim N. Taleb. Antifragile: How to Live in a World We Don’t Understand. Allen Lane. 2012.

- Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis. Rebooting AI. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. 2019.

- David Epstein. Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World. Riverhead Books. 2019.

- Doron Zeilberger. What is Mathematics and What Should it Be?

- Semir Zeki, J.P. Romaya, D. M. T. Benincasa, and M. F. Atiyah. The experience of mathematical beauty and its neural correlates. Frontiers of Human Neuroscience. 2014.

- Hubert L. Dreyfus. The Socratic and Platonic Basis of cognitivism. AI & Society, Vol (2). 1988.

- Rajiv Malhotra. The Battle For Sanskrit: Is Sanskrit Political or Sacred, Oppressive or Liberating, Dead or Alive? Harper Collins. 2016.

- Thai. Ra. Subramanian. Nachinarkkiniyar: Etic, Emic & both. IntellectualKshatriya.com. 2020.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Al-Ghazali. First published 2007; substantive revision 2020.

- Nadiaharhash. Research Paper: On al Ghazali’s Deliverance from Error (Al-Munqidh Min Al-Dalal). 2015.

- David Pears. Wittgenstein. Fontana. 1971.

- Vedanta Monthly Bulletin. Vol 1. Vedanta Society. 1906.

- Ray Monk. Turing and Wittgenstein on Logic and Mathematics. The Eighteenth British Wittgenstein Society Lecture. 2017.

- Rush Rhees (Editor). Recollections of Wittgenstein. Hermine Wittgenstein, Fania Pascal, F. R. Leavis, John King, M. O’C. Drury. Oxford University Press. 1984.

- Ravindra K.S. Choudhary. Wittgensteinian Philosophy and Advaita Vedanta: A Survey of the Parallels. D. K Print World. 2007.

- Ramchandra Gandhi. Two Cheers for Tolerance. India International Centre Quarterly. Vol. 34 (1). 2007.

- Roddam Narasimha. Some thoughts on the Indian half of Needham question: Axioms, models and algorithms. National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore. 2002.