Introduction

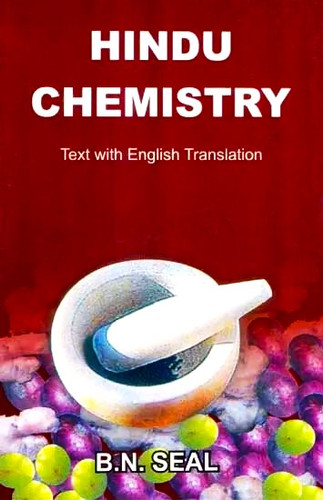

Chemistry is a complicated topic, even within the Western episteme. Equal parts hard science and traditionalist speculation, it is often conflated with alchemy. So strong is this association that Indic Chemistry is often wholly relegated to the quackery of alchemy (as Ayurveda is distanced from Medicine (Bhaisajya)). However, just as Jyotisha (Astrology) is not Jyotihsastra (Astronomy) neither is Rasayana (mercurial alchemy—pun intended) not Rasa Sastra. Though the two do often seem to intersect, Rasayana is the study of rejuvenation, often through otherwise dangerous elements such as mercury (paaradha).

In contrast, Rasa Sastra studies the full spectrum of scientific chemistry. From nuclei and atoms (anu) to the elements (dhaathu) and beyond, Indic Chemistry studied it all, and in the process produced a wide spectrum of compounds ranging from the celebrated wootz steel to myriad medicines, dyes, and perfumes.

Terminology

- Rasa Saasthra—Chemistry & Metallurgy

- Rasa Vijnaana/Rasayana—Science of Rejuvenation

- Paramaanu—Nucleus/Subatomic Particle

- Anu—Atom

- Kalaapa—Molecule

- Thrasarenu—Visible matter

- Dhravya—Substance

- Dhrava—Liquid

- Dhravaka—Solvent

- Dhravarasa—Acid

- Kshaara—Alkali

- Dhaathu—Element/Mineral

- Niryaasa/Rajana—Resin

- Visha—Poison

- Kanjika—Vinegar (Sour Wine/Fermented Rice Water)

- Bhasma—Ash

- Dhooma—Smoke

- Kvaatham—Decoction

- Ghara—Earthen jar

- Yanthra—Instrument/Machine

- Nalaka—Hollow Bamboo

- Varthika—Wick

- Majja—Pulp

- Akshupashana—Lodestone

- Ayas—Metal

- Suvarna/Hiranya—Gold

- Rajatha—Silver

- Thaamra—Copper

- Loha—Iron/Metal

- Theekshna Loha—Steel (i.e. Strong Iron)

- Yasadha—Zinc

- Vanga/Thraapu—Tin

- Seesam—Lead

- Vaikraantha—Manganese

- Kaamsya—Bell Metal

- Pittala—Brass

- Paaradha/Sutham—Mercury/Quicksilver

- Gairika—Hematite/Red ochre

- Makshika—Pyrite

- Jangala—Copper Carbonate

- Rathna—Precious Stone/Gem

- Uparathna—Semiprecious Stone

- Chapala—Bismuth

- Maanikya/Padhmaraaga—Ruby

- Tharksya/Marakata—Emerald/Beryl

- Pushparaaga—Topaz

- Vajra/Heeraka—Diamond

- Vaidhoorya—Catseye

- Muktha—Pearl

- Pravaala—Coral

- Raajaavartha—Lapis Lazuli

- Indraneela/Neelamani—Sapphire

- Soorakaantha—Sunstone

- Chandrakaantha—Moonstone [4]

- Sparshasila—Touchstone

- Kapardha/Varaataka—Cowrie

- Agnijaara—Amber

- Abhrakam—Mica

- Kacha—Glass

- Mandhura—Rust of Iron

- Sauvarchala—Saltpetre

- Gandhaka—Sulphur

- Angara—Charcoal

- Adhrija—Bitumen

- Harithala—Yellow Orphiment

- Aranda—Castor seeds

- Neeli—Indigo

- Hingula—Mercury Sulphide

- Sauvarchala—Nitre

- Thuvari—Alum

- Nilanjana—Stybnite

- Dharadha—Cinnabar

- Karpura—Camphor

- Thaalaka Varnanam—Orpiment

- Giri Sindhoora—Red Mercury Oxide

- Lavanam—Sodium Chloride (table salt)

- Navasaadhara—Ammonium Chloride salt

- Dhugdha Paasaana—Talc-Streatite

- Yavakshaara—Potash

- Sasyaka—Blue vitriol

History

“Chemistry is essentially an experimental science and has helped mankind prepare and manufacture their required materials by making use of natural resources like minerals, forest and agricultural products. Chemistry has also helped mankind prepare remedies to cure diseases and improve the health of men and animals alike.” [2, 1]

Classical Indic Chemistry naturally begins with the panchabhoothas, i.e. the 5 foundational elements of aakaasa (ether), vaayu (air), jala (water), agni (fire), & bhoomi (earth).

“Most schools believed that the elements other than ether were atomic. Indian atomism was certainly independent of Greek influence, for an atomic theory was taught by Pakudha Kaatyaayana, an older contemporary of the Buddha, and was therefore earlier than that of Democritus…

A single atom had no qualities, but only potentialities, which came into play when the atom combined with others. The Vaisesika school [of the Vedic religion] which specially elaborated atomic doctrines, and was the school of atomism par excellence, maintained that, before combining to form material objects, atoms made primary combinations of diads and triads. This doctrine of molecules was developed differently by Buddhists and Aajeevikas, who taught that in normal conditions no atoms existed in a pure state, but only combined in different proportions in a molecule (samghaata, kalaapa).” [5, 497]

Unlike the hard separation of Chemistry from Physics in Scientia (Western Science), the Classical Indic Episteme studied the two together, with the Vedic School of Samkhya providing the theistic/spiritual exegesis for matter and the universe.

Interestingly, a number of bhoomis or desas (countries) within Indic Civilization took their name from local elements (Paaradha desa) was the ancient name for Balochistan and Vanga should be familiar to anyone who’s heard of Poschim Bongo (a.k.a. West Bengal). The study of elements or minerals is Dhaathu Vidhya. This dhaathu vidhya is in turn the basis for Indian industry.

Industry

“India was considered to be the industrial workshop of the world till the end of 18th century. Everyone is familiar with the technical excellence of cast iron produced in ancient and medieval India. Tempering of steel, unknown to Europe, was brought to perfection in India.” [2, 1]

The portrayal of Katherine Mayo and even a young adult Naipaul of India as ‘An Area of Darkness’ is once again in vogue, due to the depradation of adharmic videshis on our dharma & vidhya. However, ancient and even early colonial India was a Global industrial behemoth, with economists routinely mentioning its share of world GDP in in the 20-30% range. This matter is better discussed elsewhere, but the industrial might of medieval India was in fact rooted in Rasa Saasthra.

As archaeologists have verified, the native industry was very copious and very comprehensive.“The Indus valley people used mortar consisting of lime, gypsum and sand plaster as construction materials for building houses and mansions. The Indus people were also experts in casting and forging. Copper and bronze (an alloy of copper and tin) were utilized for making tools, weapons, utensils, statuettes, finger-rings, earrings, amulets, wires and rods. Gold and silver were used for jewellery and ornamental vessels. Later excavations have unearthed specimens of iron implements.” [2, 3]

“The earliest references to the use of such materials by human beings are found in the Vedic hymns, were are the oldest recorded literature in the world.

‘I want stone, clay, hills, mountains, sands, trees, gold, silver, copper, lead, tin & iron.’

Asmaa cha me mrttikaa cha me girayascha me parvatscha me sikathaascha me vanaspathayascha me hiranyam cha me’yascha me seesam cha me thrapuscha me syaamam cha loham cha me ” – (kr.yaju.4-7-5)'” [2, 4]

“Homage to carpenters, makers of chariots, potters and smiths.’

Namasthekshabhyo rathakaarebhyo vo namah |

Namah kulaalebhyah kamareebhyascha vo namah || (kr.yaju.6-5-13)

[2, 4-8]

The industrious place of the soodhra was in artisanry. The Avesaka was crucial in the production and preservation of materiel and material knowledge.

“It is appropriate to mention that it was the Muslims, who took much of the Indian chemistry, medicine, astronomy, mathematics and other branches of science and technology to Near East and Europe. It is well established that the secret of manufacturing Damascus-Steel was taken by the Persians from India and by the Arabs from Persians.” [2, 2]

Soaps & Perfumery

Cosmetics and perfumery, like many others thinks, are routinely credited to Saracens. However, as seen in the Manasollasa and Lokopakara, these have a very antique authochthonous provenance.

“India was a leader in several chemical and pharmaceutical industries including dyeing, tanning, soap making, glass and ceramics, cement and metallurgy. Indians were far ahead of European experts in several technologies involving melting, smelting, casting, calcinations, sublimation, steaming, fixation and fermentation. They were experts in the preparation of a variety of metallic salts, compounds and alloys, pharmaceutical preparations, perfumery as well as cosmetics.” [2, 1]

“Recipe for a soap to be used as a depilatory has been given by Chakrapani as follows:

The ashes of Schrebera swietenioides and Cassia fistula are to be mixed with lime from burnt shells…The lye is then to be boiled with a definite weight of mustard oil. The plant ashes, composed mainly of potash carbonate, on treatment with lime invariably produced caustic alkali. The latter, when boiled with mustard oil, gave rise to a potash soap.” [3, 111] These are industrial soaps, and are no doubt to be used with caution.

Pyrotechnics

Saltpetre is an important component of Gunpowder (agnichoorna) which was known independently in India since the time of the Sukra Niti, and was employed in rudimentary weapons (though not rifles).

Fireworks were also not unknown and are mentioned by the traveller Abdur Razzak at Vijayanagara, which employed pyrotechnics for Mahanavami. There is also mention of the use of gunpowder in early-medieval Kashmir. Nevertheless, Sukra remains the most detailed mention to date.

“Take five palas of saltpetre, one pala of sulphur and one pala of charcoal, prepared from the wood of Calotropis gigantea and Euphorbia nerrifolia by destructive distillation; powder them and mix them intimately, and macerate them in the juice of the above-named plants and of garlic; afterwards dry the mixture in the sun, and pulverise it to the fineness of sugar. Gunpowder (lit.fire-powder) is thus obtained…If the fire-powder is to be used for a gun, six or four palas of saltpetre are to be taken, the proportion of charcoal and sulphur remaining the same as before…For a gun with a light barrel, balls of iron or of other metals are to be used…The guns made of iron or other metals are to be constantly kept clean and bright by the skilful artillery men…By varying the proportion of the ingredients, viz., charcoal, sulphur, saltpetre, realgar, orpiment, clax of lead, asafoetida, iron powder, camphor, lac, indigo and the resin of shorea robusta, different kinds of fires are devised by the pyrotechnists, giving forth flashes of starlight.’ 206-208″ [3, 225]

Indeed, saltpetre was a crucial resource that proved pivotal in the Colonial Wars. It is theorised that the capture of Bengal ultimately provide game-changing for the british. The monopoly of this resource facilitated their expansion first in the easy-to-invade plains, before finally subjugating the more mountainous plateaus and difficult-to-take deserts. That is value of saltpetre.

“It occurs extensively in Bengal and in upper India as an efflorescence on the soil. Saltpetre has been in use in India from a very early time as the basis of rocket and other fireworks. In the Dasakuramacharita by Dandi (circa 6th century A.D) mention is made of yogavartika (magic wick) and yogachurna (magic powder), of which saltpetre was probably the basis. The earliest account of the manufacture of saltpetre on a com-mercial scale in India , that has come to our notice, occurs in a work entitled, The Travels of John Albert de Mandelso from Persia in the East Indies, London, 1669. It describes the process as follows: ‘Most of the saltpetre, which is sold in Guzuratta, comes from Ajmer, sixty leagues from Agra, and they get it out of land that hath lain long fallow…when the water begins to thicken, they take it out of these pots, to set it adrying in the sun, where it grows hard, and is reduced into that form wherein it is brought into Europe.” [3, 229]

It is to be noted that Sukra described both kshudra nalika (small guns) and brhath nalika (large guns, i.e. cannon).

Colouring agents & Dyes

Ancient India was also celebrated for its beautiful textiles. Indeed, this is what dominated global trade, and Indian fabrics were prized for their redolent complexions.

“The Indus valley people were acquainted with red colour of the madder root (mangista) [manjistthaa]. There were more than 100 colouring agents of both mineral and vegetable origin and possibly a few of animal origin for dyeing the fabrics and the other articles of every day use. Indigo was the other most famous dye extracted from the plant ‘indigofera tinctoria ‘for dyeing various shades of blue. ” [2, 41]

“Another dye used in ancient India is Lac. Lac (Lakshaa) is a secretion of an insect (krmih), which is a parasite on some specific plants and trees. It contains 10% of red dye. Lac lake is the coloring matter of lac dye when precipitated from its solutions by alum (also known as Ragabhandhini).” [2, 41]

Cements & Glues

Fabrics were not the only feature of Hindus that were in fashion. The massive temples of yester-year still amaze viewers today. These were not only vibrant in colour, but have stood the test of time.

“India abounds in many temples, mansions and forts throughout the length and breadth of the country built over hundreds and thousands of years. Many of them have withstood the ravages of torrential rains, stormy winds and scorching sunshine and still maintained in an admirable condition over the centuries. How were the hefty wooden doors and window frames bound?” [2]

The use of industrial cements and glues is understudied yet of tremendous importance. From the Stupas of the Maurya era to the Deogarh Temple of the Gupta era to the forts of the Medieval era, Indic construction has stood the test of time. Unlike today’s Nehruvian deficit deconstruction, the construction of yore was rooted in Sthaapatya Veda. However, it was ultimately bound by the principles of Rasa Saasthra. The Brhath Samhitha, for example, has a chapter on Vajralepa (Adamantine Glue). These glues are known today as Ashtabandha, and are prepared on Temple grounds for fixing or restoring moorthies (statuary/idols).

“Take the unripe fruits of Tinduka [Diospyros piniculata] and kapittha [Feronia elephantum] flowers of silk cotton [Morus acedosa], seeds of Shallaki [Baswellia serrota], bark of Davana and voca [Orris root], boil all of them in a Drona [256 palas] and reduce it to an eighth part of its original volume [ie 32 palas]. Mix the sediments with the following substances viz. Shivaska [a secretion of a tree used as incense. turpentine], Raktabola [myrrh], Guggula [Commiphora roxburghii], Bhallataka [Semecarpus anacardium], Kundurooka [cunduru, exudation of Deodar] resin, Atasi [linum usikatissium] and Bilva fruit [Aegle marmelos]. The resulting paste is termed Adamantine Glue…

The book further mentions the use of glue. “When this glue, being heated, is used in the construction of temples, mansions, windows, walls and wells as well as in fixing Shiva’s Emblems and idols of gods, it will last for millions of years.” [2, 45]

Prasaadhaharmyavalabheelingaprathimaasu kudyakoopeshu |

Santhaptho dhaathavyo varsasahasthraayuthasthhayee ||

-(brhath samhitha)

“There is another adamantine glue of excellent qualities already mentioned, which is also used for the same purpose. It is composed of Lac, Kundru, Guggula, Soot [collected in the house], wood apple [Feronia elephantum], Bilva [Angle marmelos], Kernel fruits of Naga [Canthium parviflorum], Neem [Azadirachata indica], Tinduka [Diaspuros paniculata] and Madana [Randia dumetorum], Madhooka [Cynometra ramiflora] Manjishta [Rubia cordifolia] resin, myrrh and Amalaka [Emblicaofficinalis]”. [2, 45]

“Evidences have been found at Bangarh of the use of lime and surkhi as a mortar for making rammed concrete on the floor of buildings belonging to the Gupta period.” [3, 83]

Finally, even the ever denialist brits also made mention of the quality of mortar in India in the Colonial Era.

“There is an interesting report on ‘The method of making the best mortar’ at Madras in East India by one of the English Officer Hon’ble Issac Pyke published in Philosophical Transactions, Vol XXXVII, in 1732. This 250 year-old report gives details for the preparation of the mortar, its properties and its uses. This method has received appreciation and admiration in glowing terms by the foreigner.

‘Take fifteen bushels of fresh pit sand, well shifted. Add these to fifteen bushels of stone lime. Let it be moistened or slacked with water and laid for two or three days together.

Then dissolve 20 lbs of jaggery, which is coarse sugar or thick molasses, in water and sprinkling this liquor over the mortar. Beat it up together till it is well mixed and incorporated and then let it lie by in a heap.

Then boil a peck of Gram[which is a sort of grain like a Tare or between that and a pea] to a jelly and strain it off through a course canvass and preserve the liquor that comes from it.

Take also a peck of Myrabolans and boil them likewise to a jelly, preserving this water also as the other. If you have a vessel large enough, you may put these three waters together, i.e. the jaggery water, the gram water and the myrabolans. The Indians usually put a small quantity of fine lime there to keep their laborers from drinking it.

The mortar, when too dry is sprinkled with this liquor. It proves extraordinarily good for laying brick or stone. Some of the liquor is always kept at hand for the workman to wet his bricks therewith and if this liquor proves too thick, dilute it with fresh water…[though it be not usual to build common house wall thus, when the work is intended to be very strong as for instance Madras Church steeple. That was building when I was last there, and also some ornaments as columns, good arched work or imagery set up in gardens.'” [2, 49]

Gelatins

Gelatin is produced from the connective tissue of animals (such as goat and buffalo). This primarily consists of horn, hoof, and even ligaments. The boiling, dissolution, and reduction of this content results in gelatin. In harmony with its restriction on cow-slaying, ancient India nevertheless produced a number of gelatins for glue and other purposes.

The base compound might be edible (to some communities), however, the separation from the starchy components would create gelatin-based glue, which was highly effective. This type of glue is referenced by Varahamihira (a bhaaratheeya yavana-pandith) and traced to Mayasura. [2, 46]

Glass

Finally, glass and even crystal production was prolific throughout Bhaarathavarsha. Knowledge of the latter art in particular was closely guarded and is better discussed in a future article. For now, this should suffice:

“The earliest specimen of true glass in India according to Marshall was found at Taxila in the Bhir mound (circa 5th century B.C.).” [3, 78]

The chemical composition of glass found from Kopia, Basti District, Uttar Pradesh was as follows: 62.24% (Silica(SiO2)), 8.48% (Alumina(Al03)), 7.20% (Ferric Oxide(Fe2O3)), 0.51%(TItania(TiO2)), 3.13%(Lime(CaO)), 1.55%(Magnesia(MgO), 16.70%(Alkalis(NaO2), 0.20% (Manganese Oxide (MnO)).

“M.M.Nagar, who visited the locality at Kopia in1949 found countless number of tiny glass beads and glass pieces various shapes and sizes, scattered all over the place…A block of glass discovered by him was found to weigh about 120 lb. and to have a dimension of 18″x19″x12″. The block was found to contain some over-burnt brick-bats, used possibly for reinforcement.” [3, 74]

Metallurgy

“Steel has been prepared and used in India from remote ages. There is no dearth of evidences regarding the high quality of Indian iron and steel of ancient and medieval times. Thus Ktesias, who was at the Court of Persia in the 5th century B.C., mentions two remarkable swords of Indian steel presented to him by the king of Persia and his mother. The Periplus also mentions that in the 1st century A.D., Indian iron and steel were being exported from Africa to Abyssinia.” [3, 101]

Known to many today as wootz (ukku), this manufacture proliferated across the plateau of Dakshinapatha as well as Eastern India. It was, unfortunately, traded to other nations who predictably become hostile and adversarial powers. Something about capitalists selling the rope with which they are hung…

“Steel was produced in ancient India by a process resembling the modern cementation or crucible process. Wrought iron prepared directly from magnetic iron ore, as already stated, formed the starting material. This was heated in closed crucibles with dry wood chips, stems and leaves of plants over charcoal fire maintained by blowing air with large bellows. The operation was completed in 4-5 hours’ time, whereas the modern cementation process takes 6-7 days. The steel first obtained was heated again in closed crucibles whereby the excess of carbon was burnt off.” [3, 102]

And of course, who can forget the great Gupta Era Iron-pillar of Mehrauli. It was said to have been brought to its current location from eastern Uttar Pradesh. This was done in the time of King Anangapal Tomar of Delhi. That this iron pillar has refused to rust after more than 1500 years is proof-positive of the potency of Hindu chemistry.

Methodology

What is the philosophy of chemistry? Perhaps it can be described as such:

“The main goal of all these experiments described in the Rasa Sastras is two fold: one is to transform base metals to noble metals i.e. Loha Vedha and the other is to strengthen the body and maintain in a fresh and healthy state just like a youth. This is Deha Vedha or Kaya Kalpa.” [2, 21]

Dhaathu Vidhya is Minerology. “In the HIndu Materia Medica the mineral kingdom is broadly divided into the rasas, the uparasas, the ratnas (gems), and the lohas (metals. The term rasa is in general reserved for mercury [paaradha], though it is equally applicable to a mineral or metallic salt. In the oldest medical works, e.g. the Charaka and the Susruta, rasa has the literal meaning of juice or fluid of the body” [3, 166]

As a result, Rasa Saasthra is not only instrumental in the manufacture of industrial materials, but also in the preservation of health and its restoration via dravya guna, as well as the gustatory pleasures of paka sastra. This in turn brings in the concept of Rasa itself as well as the shadruchi (6 essential flavours/tastes).

Rasa

The theory of thriguna, thridhosha, and panchamahabhootha is known to many. However, the utility of their application to rasa saasthra is less discussed. Indeed, the combination of the different elements forming the basis for shadruchi has immediate relevance to chemistry. Acids are routinely described as aamla, though perhaps better delineated as dhravarasa.

“Rasa is believed to be evolved from Antareeksha or Divya Jala. It is devoid of taste. As soon as it came in contact with the panchabhautika soil, it attains rasa according to the predominance of panchamahabhoota in it…Panchamahabhootas will represent the elements and compounds of modern chemistry and accordingly the tastes are the results of some chemicals.” [1,11]

Different Acharyas assert different bases for tastes. As per Acharya Charaka, they are as follows:

- Madhura (sweet) = Apah (water) + Prithvi (earth)

- Aamla (sour) = Prithvi (earth) + Agni (fire)

- Lavana (salt) = Apah (water) = Agni (fire)

- Katu (pungent) = Vaayu (wind) + Agni (fire)

- Tikta (bitter) = Vaayu (wind) + Aakaasha (ether)

- Kashaaya (astringent) = Vaayu (wind) + Prithvi (earth)

Interestingly, the panchamahabhoothas are viewed as aadhibhauthika (primordial) and are deemed as visesha guna. “They are mainly useful in the diagnosis of the diseases. For example with the help of shabda guna we can diagnose the rasakshaya by seeing shabda asahishnuta (intolerance to high frequency sound waves) and accordingly we can adopt treatment by giving jaliya substance and also musical therapy in some maanasika vikaaras” (mental conditions). [1,21]

Divisions

Basic chemistry divides useful substances (dhravyas) as follows: gold, silver, copper, tin, lead and iron are described as the 6 fundamental metals (loha or ayas). Varthaloha/Varthaayas refers to metal alloys such as bronze. Rathna refers to precious stones or gems, such as diamond or ruby.

The maharasas are 8 major substances that are deemed the most powerful. These are makshika (copper pyrites), vimala (another pyrite), sila (rocks), paaradha (mercury), dharada (cinnabar), sasyaka (blue vitriol), rasaka (calamine), chapala (sulphides). The rasas that are commonly used are mica, green vitriol, lapis lazuli, collyrium, vaikranta and borax. The uparasas are the lesser substances, such as sulphur, orpiment and realgar.

All this is per the Rasakalpa. [3, 156]

Chemist & Staff

Chemistry in Ancient India necessitated an high order of knowledge and skill not just in the rasakaara (chemist) but also in the rasakarmaani (staff member).

“Professional discussions are to be carried out in a friendly atmosphere

‘One should have friendly discussion with persons of learning, possessed of scientific knowledge, proper argument, who did not get irritated, who are endowed with correct knowledge, who are competent in convincing others, who are capable of facing difficult situations and who can address in a sweet tone.” [2, 28]

“Thus a very high standard was set for such technical conferences in ancient India. CS (Charaka Samhitha] also provides guidelines for selection of teachers, students and textbooks connected with the medical education…who is free from vanity, envy and anger, who is hard working, who is effectively disposed towards the scriptures and is capable of expressing his views with clarity. A preceptor, possessed of such quality infuses medical knowledge to good disciples as the seasonal clouds help bring about good crop in a fertile land.” [2, 29]

The Chemist is expected to maintain a high degree of not only practical knowledge, but professional decorum. After all, he is not merely handling paints and pencils, but literally combustible materials. This also necessitates proper discussion rather than debate to oblivion, in order to ensure clear transmission of crucial knowledge. “The performer of chemical operations should be fully dedicated to the field of chemistry. He should know the chemicals and the drugs in all their aspects including the technical terms. He should know many languages of different countries. he should be pious, virtuous, truthful, very learned and also kind hearted…

“He should be free from greed, capable of controlling passion and senses and restricted in the diet to what is normally good for health. Such a person alone is considered fit to maintain the laboratory and prepare Rasayanas (rasaayanaani). A person is rich, generous and highly accomplished follows the teachings and advices of his teachers. A person who is familar and well versed with the different names of the chemicals and drugs, clean hearted and free from cheating and possess the knowledge of different subjects and languages should direct the laboratory. The attendant should be active in his work and persevering. He should be clean hearted, physically strong and courageous.” [2. 20]

Application

A pound of practice is worth a tonne of theory. As a result, the application of chemistry necessitates an order of magnitude more caution than the mere memorisation of its texts.

A laboratory would be set up with a designated functional zone for the 8 cardinal directions. There was a vedhakarma (Transmutation Bay) in the North, Material storage in the Northeast, presiding deity statue in the East, Furnace in the Southeast, Stone instruments in the South, Sharp instruments in the Southwest, Washing Bay in the West, & Drying Bay in the Northwest. [2, 16]

The chemist and his attendants would be expected to be vigilant to all dangers and attendant to ongoing processes and operating mechanisms. Equipment was expected to be carefully constructed and cleaned routinely.

Equipment

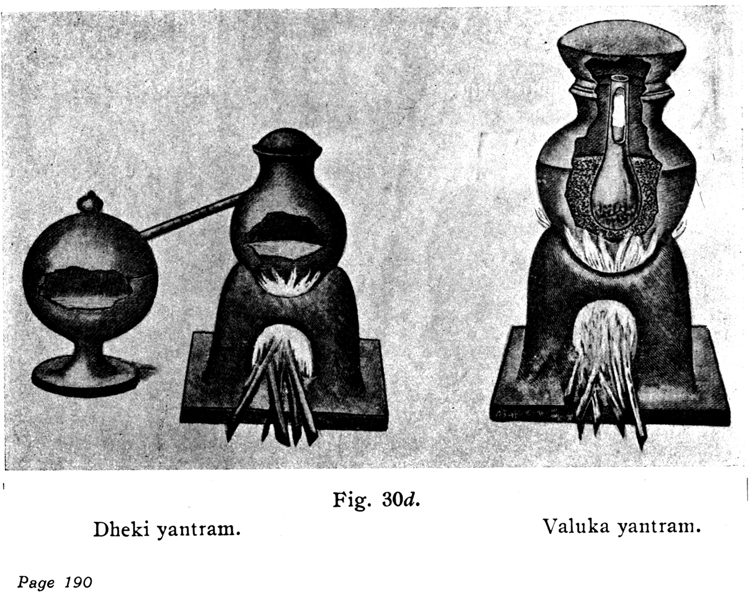

“There were more than 32 pieces of apparatus used for chemical and pharmaceutical investigations and they are called Yantras (yanthraani). Descriptions of only three Yantras viz.Kosthi Yantra, Tiryak Patana Yantra and Deki Yantra are given for illustration.” [2, 17]

Equipment of the period ran the gamut from earthen jars and bamboo pipes to furnaces and decoction contraptions. The Kosthi Yanthra, for example was used for extraction of Sattva (metal content from minerals). The Rasatha Samucchaya describes the instrument in detail and how charcoal in the furnace is used. [2, 18]

“Kosthi apparatus is used for the extraction of metals from the ores. Water, vessels and the apparatus are for the distillation of alcoholic preparations. A pair of bellows and pipes of bamboo and metal are also essential. Iron crushers, grinders, boat shaped and round mortars for grinding ingredients are necessary in the laboratory. Heatable iron mortar, vessels of the same type, sieve having thousands of holes, cloth pieces, rods and sticks, circular rings and frames, soil suitable for making crucibles, husk, cotton…etc. are required for the laboratory experiments.” [2, 15]

Then there is the Thiryaka Patana Yanthra, which is used for distillation. “Place the chemicals in a vessel provided with a long tube inserted in an inclined position, which enters the interior of another vessel arranged as a receiver. The mouth of the vessel and the joints should be luted with clay and cloth. Now put a strong fire at the bottom of the vessel containing the chemicals, while the other vessel is in cold water.” [2, 18]

Third, is the Dheki Yanthra: “Below the neck of the pot is a hole into which is introduced the upper end of a bamboo tube, the lower end of it fitting into a brass vessel filled with water and made of two hemispherical halves. Mercury mixed with the proper ingredients is subjected to distillation till the receiver gets sufficiently heated.” [2, 19]

Other contraptions utilised in the manufactury of goods or production of compounds include the Dhoopa Yanthram (fumigating apparatus) and Vrnthaaka Yanthram (Aubergine Crucible). [3, 191] Other devices included the closed crucible (andhamusha) used for metal purification, but for brevity’s sake, we will expound upon the remainder later.

Essential to the practice of chemistry beyond its equipment and raw materials, are the resultant compounds.

Acids

“The preparation of mineral acids is incidentally des-scribed in several exclusively medical works, composed probably in the 16th and the 17th centuries; e.g. in Rasakaumudi by Madhava, Rasaratnapradipa and Bhaishajyaratnavali by Govindadasa ” [3, 229-230]

Acid is one of the essential components to the study of chemistry. It is defined in modern chemistry as an atom that loses its subatomic particles to a more receptive one. It is characterised as a sharp or sour material (acidus in Latin) that can break down another. This is particularly edifying as acids are often referred to as aamla (sour) in Sanskrit texts. However, as per dhravya guna, acids are better termed dhravakas or dharavarasas.

“Description for preparing mineral acids by distillation: —Smakhadravarasa or liquid for dissolving conch-shells; this is to be prepared by distilling a mixture of alum, sal-ammoniac, saltpetre and sulphur. Cowrie-shells and metals dropped into the liquid are at once dissolved.” [3, 197]

This ability to breakdown other materials is often termed “the killing” of a substance. The killing of iron is on such example.

“One of the most important chemical activities carried out in such a well-equipped laboratory was known as the killing of metals. Suphur was used to ‘kill’ all the metals and suphur was known as the enemy of metals (copper) ‘sulvaari’ (sulva+ari), which finally became Suphur in English. Sulphur is compared to a lion and a metal to an elephant. ‘Just like a lion kills an elephant, sulphur kills all the metal.” [2, 21]

“What wonder is that Calaine (rasakah), one of the zinc ores gets converted into gold when roasted with copper (sulva) three times.’ Today we understand that when Zinc ore is roasted with Copper or Copper ore, brass is produced. This yellow metallic alloy resembles the colour of Gold and hence this ancient claim.” [2,22]

“Ancient scientists also observed that base metals like Iron easily undergo corrosion while the noble metals do not. In their assessment, among the six metals God, Silver, Copper, Iron, Tin and Lead, the resistance to waste (corrosion) is in the order in which they have been named.

Sarvanam rajatham thaamram theekshavangabhojangamaah |

Lohakam shadvadham thaccha yathaapoorvam thadhakshayam || – (rasarnava: -7-89, 90)” [2, 22]

Alkalis (Caustics)

“The three alkalies are the borax, trona (natron) and yavakshara (carbonate of potash). The ashes of sesamum, Achyranthes arpera, Musa sapientum, Butea monos-perma, Morigna pterygosperma, Schrebera swietenioides, Raphanus sativus, Zingiber officinale, Tamarindus indica and Ficus religiusa respectively are regarded as the standard plant ashes.” [3, 137]

Alkalis are substances that can turn fats into soap. They are typically termed as caustics and closely connected to various salts. The importants of salts was known to the Ancient Indians. Alkalis were divided into mrdhu (mild ), madhyama (middling), and theekshna (strong) per the Sushruta Samhita. The existence and use of Borax was also mentioned. [2, 64]

“Various types of salts have been distinguished by Kautilya; viz. saindhava, derived from the country of Sindhu; samudra, produce from sea-water; bid; yavakshara, literally ashes of barley (potash), but often employed for nitre; sauvarchala, derived from the country of Survarchala; udbhedaja, that which is extracted from the saline soil.” [3, 56]

The prepartion of metallic salts was termed ayaskrithi. [3, 66]

“Caustic alkalis play an important role in our daily modern life. They are essential for a variety of industries, which manufacture consumer articles for daily life such as paper, textiles, soap and detergents, plastics, medicine, metallurgy and several other industries. Today over a million tons of caustic soda are manufactured in India every year from sea salt by electrochemical methods. Our ancestors in India however, prepared this essential commodity from wood ashes, limestone and seashells. The details fo the method of the preparation of alkali are described in Sushruta Samhita (SS).

‘Some well-grown trees in the forest are cut into logs and these are piled in a place free from strong wind. Lime stone/sea shell should be placed one the piles and then set on fire by stalks of dry plants. When all the wood is burnt out, the fire is extinguished, the ashes of the logs and the burnt lime are collected and kept separate and dissolved in water. The extract of the ashes is then mixed with limewater to get lye, which is separated from the precipitate by filtration. The solution is concentrated to different extents by boiling and it is possible to get dilute, mild and caustic alkali. (mrdhu manda theekshna kshaara).'” [2, 13]

“Wood ash contains potassium and sodium carbonates (K2CO3 & NA2CO3). Limestone and seashells contain calcium carbonate (CaCO3). On heating strongly, the carbonate decomposes into calcium oxide (CaO) ‘quick lime’ and carbon dioxide (CO2), which excapes into the air. Calcium oxide reacts with water vigorously and gives calcium hydroxide (CaOH2) which is lime water indeed…This was the most efficient and scientific method of preparing caustic alkali until the end of 19th century when electrochemical method became more popular.” [2, 14]

Sulphides

Sulphides were copiously produced in Ancient India. From mercury to iron and beyond, they were deployed for myriad purposes.

Tamrayoga (Copper compound)

‘Take a thin leaf of Nepalese copper and embed it in powdered suphur. The subtances are to be placed inside a saucer-shaped earthenware vessel and covered with another. The rims are luted with sugar or powdered rice paste. The apparatus is heated in a sand-bath for three hours. The copper thus prepared is pounded and administered with other drugs.’

The product of the reaction is obviously a sulphide of copper.” [3, 110]

Medicine

Medicine (bhaisajya) is quite possibly the most fundamental application of Indic Chemistry. From powders and pills to concoctions and decoctions to antivenin itself, sound understanding of chemistry was required to ensure patients were properly treated with patience.

“The Bhava Prakasa, written about 1500 A.D., prescribes calomel in the treatment of phirangaroga (lit.the disease of the portugese; i.e. syphilis) and gives the following recipe: “Take of purified mercury, gairika (red ochre), brick-dust, chalk, alum, rock-salt, earth from ant-hill, kshari lavana (impure sulphate of soda), and bhandaranjika or red earth, used in colouring pots, in equal parts; rub together and strain through cloth. Place the mixture in an earthen pot, dover it with another pot…and the white camphor-like deposit in the upper part is collected for use.” [3, 207]

It is a pity that Jawarharlal Nehru so disparaged Hindu-culture for the Western, himself being enamoured and afflicated with a phirangini. Had he not done so, he might have made use of this treatment for the ailment he contracted in his later years…

“The chemical reactions, involved in the above methods for the preparation of calomel, may be explained as follows: Alum, magnesium sulphate or ferrous suphate, when heated yield some sulphuric acid. This reacts with common salt to liberate hydrochloric acid. The latter undergoes aerial oxida-tion in contact with ferric oxide from the brick dust, gairika, clay, etc., acting as a catalyst, and sets free chlorine,which attacks the mercury, giving rise to calomel. Alumina from alum or from clay may also catalyse the reaction to a certain extent like the ferric oxide.” [3, 207]

Key Personalities

Sushruta

Charaka

Vagbhata

Varahamihira

Siddha Nagarjuna

Bhavamishra

Bhikshu Govinda

Vrindha

Chakrapani

Yasodhara

Somadeva

Baalabhadhra

Brahmajyothi

Gaha Nandhanaatha

Manthana Bhairava

Nadhi

Svacchanda Bhairava

Vyadhi

Important Texts

“There are about 44 known ancient and medieval Samskrit texts on a technical subject such as chemistry alone”. [2, iii-iv] Here are some of the most important ones.

Sushruta Samhita

Charaka Samhita

Bhava Prakaasha by Bhava Mishra

Rasarathnaakara

Rasarnava

Rasahrdhaya

Kakachandesvarimatham

Rasendhra Choodamani

Rasa Prakaasa Sudhaakara

Rasa Chinthaamani

Rasakalpa

Rasarathna Samuchhaya

Rasaraaja Lakshmi

Rasanakshathra Malika

Dhaathu Rathnamaala

Dhaathukriya Dhaathumanjari

Rasaarnava Kalpa

Sarveshvara Rasaayana

Dhaathuvaadha (Tibetan Texts)

Dhivya Rasendhrasaara by Dhanapathi

Gahanandhanaatha

Rasarathnaavali by Garudadhatthasiddha

Goraksha Samhitha by Gorakshanaatha

Banddhasarvasava

Rasesvara Siddhaantha

Rasavisva Dharpana by Harihara

Rasa Kankali by Kankali

Rasaraaja Mahadhadhhi by Kapali

Yogarathnaakara by Kesavadeva

Rasa Kautuka by Mallari

Rasayoga Mukthaavali by Narahari

Rasarathna Pradheepa by Raama Raaja

Rasendra Bhaaskara by (Siddha) Bhaaskara

Rasadheepa by (Siddha) Praananaatha

Rasarathna by Sreenaatha

Rasadharpana by Thrimallabhatta

Rasakashaayavaidhyaka by Vaidhyaraaja

Yogasudha Nidhi by Vandhimisra

Rasasarvesvara by Vasudeva

Rasa Dheepika by Anandanubhava

Rasaraaja Mriganka by Bhojadeva

Rasanchandhrodhaya by Chandrasena

Charpata Siddhaantha by Charpata

Conclusion

Modern India, or Post-modern India rather, is at a crossroads. On the one hand it has a proliferation of bloviating bloggers who are long on hyperbolic pontification and performative attention-seeking, and short on actual constructive work. On the hand, Bhaarathavarsha is facing a civilizational smear-campaign like never before. It can be summed up as: “We want what’s yours without you or permitting esteem to you.” Said an other way: “We claim what’s yours in order to give civilization to you“. Indeed, much of it hearkens back to a century ago.

“Recent research by Sri Dharampal and others have shown that the colonial invaders and rulers had vested interest in distorting and destroying the information regarding all positive aspects of Hindu culture.” [2, iii]

Our useful idiots (the higher the caste supremacist, the more useful the idiot…) are only too happy to oblige, uploading all sorts of nonsense to placate their performative attention-seeking. As a result, much like Yoga is separated from its scientifically-verified benefits, all Indian chemistry is conflated with mere alchemy.

“The conventional understanding today is that Hindus were only concerned about rituals, spirituality and the world after death. Contribution of Hindus to the field of astronomy, fundamental particles, origins of universe, applied psychiatry and psychology and so on are not well documented and relatively unknown. Ancient Hindus had highly evolved technologies in textile engineering, ceramics, printing, weaponry, climatology, meteorology, architecture, medicine and surgery, metallurgy, agriculture and agricultural engineering, civil engineering and town planning.” [2, iii]

An introductory article such as this can only delve into so much before reaching the end of brevity. A companion article will therefore follow this one to balance breadth with depth. The full spectrum of Indic knowledge, indeed chemistry alone, can take up reams. The juxtaposition with modern science stretches word limits even more.

“Comparison of contemporary developments in science and technology to the works of ancient Hindus is inappropriate. Objectives, methodology, frames of reference and data are different for both. Contemporary science, generally perceived as Western development, seeks to understand nature more with a sense of conquering nature for subsequent exploitation of the same.” [2, iv]

“The phraseology ‘the scientific traditions of Hindus’ is in itself a misnomer as it was the Hindu who first conceptualized the process of science. Pratyaksha-anumana-agama-pramana and the various methods of deriving knowledge and proof have been discussed extensively in various ‘Darshanas’.” [2, iv]

As a result, this article centred its purpose on a basic introduction to the scripture of chemistry, that is Rasa Saasthra. Like any scripture, the sacred essentials of a Saasthra don’t change (as with mokshasaasthra and dharmasaasthra for example). However, vidhya expands or contracts over time. In the present time, the needs are different given the devolving state of mankind, and Indians in particular.

“A positive image of one’s heritage (for history is a conscious effort of what we want to remember) is essential for the communities to develop self-esteem, self-confidence, which are prerequisites for growth and resurgence of communities. Individuals and communities with such self-esteem can contribute to the progress of India and for the welfare of mankind. The documentation and dissemination of India’s scientific heritage is essential from this point of view.” [2,v]

A predisposition for exaggerated claims and bigmouthed breast-beating helps no one. Referencing Hindus deities as proof of plastic surgery is even more self-defeating given the ample evidence in the Sushruta Samhita of such surgeons. It is imperative than Indian teachers not just communicate knowledge or thrash disobedient students, but assertively instill emotional discipline in them. This becomes all the more crucial in a literally combustible field such as chemistry. It is neither for the useful idiot nor for the idiot-savant.

The story of the tiger and four brahmins is illustrative here. It is important not just to learn the methods and prove our intelligence, but also to gain the wisdom of when & where to use them.

“Hindus belong to a race, which has dwelled on the most fundamental questions about life, death, nature and its origin. Bold questioning by Hindus has given birth to theories, axioms, principles and a unique approach to life.” This approach has led to the evolution of one of the most ancient and living cultures on the face of the earth.” [2,iii]

Click here to Buy this Book!!!

References:

- Mehatre, Dhulappa (Dr.). A Text Book of Practical Dravyaguna Vignana. Chaukhambha Orientalia Varanasi.2016

- Murthy, A.R.Vasudeva & Prasun Kumar Mishra. Indian Tradition of Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Bangalore: Samsrita Bharati.2013

- Ray, P. & Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray. History of Chemistry in Ancient and Medieval India. Varanasi: Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy. 2022

- Sen, Madhu. A Cultural Study of the Nisitha Curni.Amritsar: Sohanlal Jaindharma. 1975

- Basham, A.L. The Wonder that was India. New Delhi: Rupa.1999