Lumos

“What is the difference, Potter, between monkshood and wolfsbane?”

… For your information, Potter, asphodel and wormwood make a sleeping potion so powerful it is known as the Draught of Living Death. A bezoar is a stone taken from the stomach of a goat and it will save you from most poisons. As for monkshood and wolfsbane, they are the same plant, which also goes by the name of aconite.” – J.K. Rowling [1].

This first part of the essay traces the western history of the Bezoar, which has been depicted as an ultimate antidote. Wolfsbane, which plays its evil twin is discussed in the sequel. The Bezoar-Wolfsbane pair appear to be a marker of knowledge transmission across civilizations. As we search the forbidden forests of history, we find Indic contributions hiding in plain view in unexpected places.

Medieval Arabic Descriptions

(All emphases within quotes are mine)

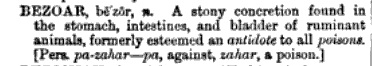

Western accounts trace the Bezoar to 9th-11th century Arabia and Persia. English dictionaries attribute the origin of the word to the Persian pad-zahar for ‘anti-Poison’, which was corrupted to the European bezar and bezoar [2].

An article [4] that studies the Arabic origin of some English words says:

“.. In medieval Latin, bezoar is bezahar in the late-12th-century Arabic-to-Latin translations of the medical books of Ibn Sina (died 1037) and Al-Razi (died c. 930) … It is lapis bezaar | lapis bezahar in the late-13th-century Arabic-to-Latin translation of the medicines book of Serapion the Younger …“.

Important Arabic texts like Al Beruni’s book on mineralogy ‘Kitab al–jamahir fi ma’rifat al jawahi’ in the 10th-11th century CE, and Jewish texts by Moses Maimonides in the eleventh-twelfth century CE refer to Bezoars [7]. Al-Beruni is known to have traveled through India and studied its traditions and we share excerpts from a translation [3] of his book:

“… this stone should have been the costliest among stones, for, whereas jewels are things of the body and adornment, and are of no use in bodily ailments, the bezoar stone guards the body and the soul and saves them from being harmed… Hamzah and Nasr both say that it is primarily associated with India and China…

“Hajar al-’l’ays (animal bezoar) is a Persian theriac... It is taken out of the stomachs of the mountain goats, but is of a very rare occurrence. It is called hajar al-tays for this reason, tays meaning the he-goat. Some through apocopation and orthographic error called it hajar al-bīsh. But this orthographic error is very true, correct and noble, since it is a theriac for aconite poisoning …”

Hajar ~ stone in Arabic and Aconite ~Wolfsbane. Note the transcendental and material properties attributed to Bezoars by Al-Beruni. ‘Bīsh’ was a word also used by other Arab scholars including the distinguished eleventh century Islamic scholar Ibn-Sina who learned from Indian knowledge systems and acknowledged this fact.

Arabia to Europe: Gayat Al-Hakim to Picatrix

Many in Europe were introduced to Bezoar stones and Wolfsbane (alcondiz in Medieval Latin [11]) through references in the Picatrix, the 13th century Latin book on astrology and magic. Picatrix is a translation of the Arabic text Gayat Al-Hakim (the Goal of the Sage) dated to ~tenth century. Going by their titles, the Hogwarts school library seems to be a more suitable place for these books, but scratch deeper and we find research material that merits the attention of Swadeshi Indologists.

The remainder of this section is devoted to an initial study of these works from an Indic perspective. The Bezoar story resumes in the next section.

What’s really interesting about Gayat Al-Hakim are the references to Hindu deities, profound Vedic concepts, and ideas in Jyotisha. Hasan Ali Khan, is his book ‘Constructing Islam on the Indus’ [14] states its content: “A medieval Arabic text on Indian astral magic, Ghayat al-Hakim, comes to the aid of the Suhrawardi Order in Uch, by throwing new light on the subject of Shaivism. It gives the names of the Hindu deities that preside over the major planets ..”.

Saif et al. [5] in their work that surveys medieval Islamic talisman and magic, delineate the basis of Gayat-Al-Hakim: “The magic of The Goal of the Sage is based on the knowledge of correspondences– that is, the rules of sympathy or antipathy among animals, plants, minerals, even colors and scripts, on the one hand, and celestial/spiritual entities on the other. The magic of this text can be considered astral, natural, and spiritual. The operator in this case needs to have a vast knowledge of planets, signs, and lunar mansions in addition to information on all kinds of animals, plants, and minerals that correspond to the powers of the celestial bodies.“. This correspondence is the basis of its Latin translation as well.

This foundation of Gayat-Al-Hakim reflects a medieval Arabic understanding of the fundamental Vedic correspondence and resemblance principle: Bandhuta or Bandhu [18]. Compare the previous paragraph with this original Hindu concept that Rajiv Malhotra has expounded upon in his path-breaking book ‘Being Different’ [6]:

“Bandhu is a concept used to explain how the whole and the parts are held together in integral unity. All aspects of the world stem from a common ineffable source, and what we perceive as nature is but a pointer to a higher reality. There is interlinking among the various faces of this reality, such as sounds, numbers, colours and ideas, and this interlinking is bandhu. The subtle and transcendental worlds on one side correspond with the perceptible world on the other. The term describes the relationship of the microcosm to the macrocosm wherein the former is a map of the latter, and paradoxically one mirrors the other…

… The Vedas abound in attempts at finding connections among the numerous planes of reality. This serves as a cardinal principle of all Vedic thought and moral discourse.”.

"All schools of Vedanta agree that there is one Ultimate Reality that is Supreme Consciousness and that there is nothing independent of this reality. This Ultimate Reality is the raw material that turns itself into the universe." - Rajiv Malhotra on Hinduism's integral unity [6].

The aforementioned microcosm-macrocosm relationship is a central element of Vedic Yajna, an important Sanskrit non-translatable for which no Arabic or European equivalent exists. The presence of key Sanskrit non-translatables in the original Vedic description yields a reductive rendition (digestion) unless these keywords are retained as is in the translation [6]. For example, the magical trio enumerated in Gayat-Al-Hakim, namely, natural, astral, spiritual is an epistemically weakened reading of the original trinity in Vedic cosmology: Adhibhuta, Adhidaiva and Adhyatma who are integrally united via Bandhus.

The sustained influence of Picatrix on European thought and expression has been documented by western scholars. In addition to the Hermetic, esoteric, and mystical traditions in Europe [13], its impact on the European Renaissance has been recognized. In his book ‘Astrology in the Renaissance : The Zodiac of Life’, the Italian scholar and expert on the cultural history of the Renaissance, Eugenio Garin (1909-2004) recognized the key role of Picatrix in this regard [12]:

“.. given the need to have it constantly to hand, not only as a real source, though obviously not declared as such, but also as a document illustrating a general position and way of thinking: for all these reasons it is fitting to pay it more attention than is usual. In reality the Latin version of the Picatrix is as indispensable as the Corpus Hermeticum or the writings of Albumasar for understanding a conspicuous part of the production of the Renaissance, including the figurative arts. “.

Let’s review an example.

Vedic Basis of The Vitruvian Man

Leonardo Da Vinci is recognized as the most famous personality of the European Renaissance. One his most iconic works is the 15th century masterpiece: the Vitruvian Man inscribed within a square and circle.

By Leonardo da Vinci – Leonardo Da Vinci – Photo from www.lucnix.be. 2007-09-08.

The rendering of the sketch, based on Da Vinci’s accompanying notes, are attributed to the description of symmetries in the human body in Book-III of the Latin work De Architectura (~30 BCE) of the Roman architect Vitruvius that resurfaced in the early 15th century. Book-III recommends a design of temples using the relative proportions and visible symmetry of the human body as analogy [20]. There are several other ‘Vitruvian men’ sketches of that era. However the vision and scope of these sketches go far beyond such design considerations:

"Leonardo envisaged the great picture chart of the human body he had produced through his anatomical drawings and Vitruvian Man as a cosmografia del minor mondo (“cosmography of the microcosm”). He believed the workings of the human body to be an analogy, in microcosm, for the workings of the universe."

- Encyclopedia Britannica Online [15].

Picatrix influenced many Italian and European intellectuals of that time. It is known to be the basis for the fifteenth century trilogy of books on Occult Philosophy by Renaissance writer Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa [13], whose own Vitruvian-man sketch (‘Man in a Pentagram‘) has been viewed along similar cosmological lines.

The parallels in the iconography of these sketches, and the Purusa and altar geometry in Vedic Yajna discussed in the ancient Sulba Sutras (no later than 800 BCE) have not gone unnoticed, and James Kelley [16] presciently ponders this question: “it appears possible that a central symbol of ancient Indian religion―the archetypal man with limbs outstretched—may be the origin of that image that so haunts our Western minds: the Vitruvian Man, whose measurements purport both to illustrate the secret of the squared circle and to show forth the sacred proportion that undergirds the cosmos“.

Here, we substantiate its epistemic roots: these sketches reflect a Renaissance-era digestion of the original Vedic principle of correspondences. The following line in Garin‘s essay [12] on Picatrix encapsulates Da Vinci’s way of thinking.

"Doubtless we are on a different track with Leonardo, far from magicians and astrologers, even if for him man is still a microcosm, and so an integral part of the whole, symmetrical and linked to the whole by infinite and mysterious bonds." - Eugenio Garin.

The 10th-13th century CE time period witnessed a mass transfer of Indic knowledge from India to the west through similar reductive translations: from Sanskrit to Arab/Persian to Latin and other European languages. For example, Ganita revolutionized a Roman-numeral bound Europe emerging from the dark ages.

This preliminary analysis reveals a latent but significant Indic influence on Western thought and artistic expression prior to European entry into India. Gayat-al-Hakim and its Latin translation Picatrix have served as an early vehicle of digestion [6] of key Vedic concepts into the then nascent Islamic thought, European ‘Pagan’ traditions, and the Renaissance itself.

Footnote: A most prominent western work on Gayat-Al-Hakim [19] is by the famous Indologist David Pingree. He authored many academic treatises after studying Jyotishastra and other Sanskrit texts for decades without letting their profound wisdom illuminate and dispel his Eurocentric prejudices.

https://indicportal.orgvedanga-jyotisha-indology/

India to Europe

Between the 13th and the 16th century, Bezoars made their way into Europe as their royalty became paranoid about being poisoned by plotters. The rare Oriental Bezoar became a prized possession among the wealthy, driving up its demand and price. The story of how the knowledge about Bezoars traveled to Europe has been well studied [7] and some of the writings of interest include the 1563 work by Garcia da Orta: Colóquios dos simples e drogas da India or the “Simples and drug colloquies from India” that gained credibility in Europe:

“Unlike scholars of the stature of Mattioli, Laguna, Gessner and Aldrovandi, who develop their work in Europe, Garcia da Orta claimed to have first hand knowledge acquired during travels throughout India which allowed him access to materia medica, natural remedies and medicines, from faraway lands” – [7].

Garcia mentions the use of the Bezoar stone in Goa. Those aware of how Ganita’s time-keeping and Calculus traveled from India to Europe would not be surprised by the uncanny ability of Jesuit priests to show up in the right place at the right time. In this case, they cashed in on the Bezoar craze in Europe: “Jesuit priests in Goa, India formed shells, silt, amber, resin and sometimes bits of actual bezoars and crushed gemstones into hardened balls called Goa stones. These were also believed to counteract poison and cure the plague and were fabulously expensive” – [2].

Within a decade, more books were written that served the purpose of improving the European understanding of medicines and antidotes obtained from the ‘Orient’. Soon after, ‘Occidental Bezoars’ from South America too began to be procured [7] although the more reliable Oriental version remained a prized possession!

By the 16th century, use of bezoars was widespread among the very rich — they were valued at 10 times their weight in gold. Queen Elizabeth I even had a bezoar set in a silver ring - [2].

This was the period of the next wave of knowledge transfer directly from India to Europe in multiple scientific disciplines. It preceded a string of scientific findings there after European scientists and intellectuals recast and extended Indic results to fit within their own civilizational framework (e.g. reworking the Calculus invented by Ganita scholars in Kerala centuries earlier). Unlike the first wave, where the Arab scholars did not hide the Indic roots of their learning, the Jesuit priests and European researchers digested and claimed what they wanted without crediting the original Indic sources.

By the 17th century, the Bezoar’s fame and notoriety peaked in Europe even as the general understanding of Bezoars remained poor. Consider the landmark case of English common law in 1603: Chandelor vs Lopus [17]. A hundred pounds was paid to a seller to acquire a Bezoar that later turned out to be a fake stone. A lawsuit resulted and the seller eventually got away without punishment. The resultant legal repercussions lasted a couple of centuries.

The western side of the story pretty much stops here but leaves enough pointers regarding the original source traditions that nurtured the science of antidotes.

Provenance

In his 1807 book on natural history [9], Buffon states that the ancient Greeks and Romans had no knowledge of the Bezoar and where to find them. He mentions that the Arabs knew about the properties of the Bezoar but could not clearly describe the animals that produced it. And then there’s the mysterious but deadly Wolfsbane. Where then can we find the indigenous traditions that systematically analyzed, validated, and updated the knowledge regarding such toxins and precious medicines since the most ancient of times, and maintained a continuity of this understanding throughout history?

In the concluding part, we explore the Indian origins of this knowledge.

References

- J. K Rowling. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. 1997.

- Loraine Fick. The Magical Medicine of Bezoars. science.howstuffworks.com. 2019.

- Abu Rayhan Muhammad Ibn Ahmad Al-Biruni. The Book Most Comprehensive in Knowledge on Precious Stones: Al-Beruni’s book on mineralogy. Edited by Hakim Mohammed Said. Pakistan Hijra Council. 1989.

- Collection of etymologies and word histories of English words that came from Arabic words. 2017.

- Liana Saif, Emilie Savage-Smith, Venetia Porter. Amulets, Magic, and Talismans: Blackwell’s Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture. 2017.

- Rajiv Malhotra. Being Different: An Indian Challenge to Western Universalism. Harper Collins. 2011.

- Luis Millones Figueroa. The Bezoar Stone: A Natural Wonder in the New World. Hispanófila Vol 171. 2014.

- Garcia de Orta. Coloquios dos Simples e Drogas Da India. 16th century CE. Archive.org.

- Georges Louis Leclerc comte de Buffon. Buffon’s Natural History: Containing a Theory of the Earth, a General History of Man, Of the Brute Creation, And of Vegetables, Minerals, etc. etc. Vol 8. 1807.

- Hashem Atallah (Translator), William Kiesel (Editor), Maslamah ibn Ahmad Majriti (Author). Picatrix (Ghayat Al-Hakim) The Goal of the Wise. Vol. 1. Ouroboros Press. 2002.

- Dan Attrell (Translator), David Porreca (Translator). Picatrix: A Medieval Treatise on Astral Magic (Magic in History) 1st Edition. Penn State University Press. 2019.

- Eugenio Garin. (Excerpts) Picatrix in Renaissance Astrological Magic. 1976.

- Peter Levenda. The Tantric Alchemist: Thomas Vaughan and the Indian Tantric Tradition. Ibis Press. 2015.

- Hasan Ali Khan. Constructing Islam on the Indus: The Material History of the Suhrawardi Sufi Order, 1200-1500 AD. Cambridge University Press. 2016.

- Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Leonardo Da Vinci – Anatomical Studies and Drawings.

- James L Kelley. Prajapati Purusa and Vedic Altar Construction. 2018.

- English Legal History and its Materials: LopusChandler. http://moglen.law.columbia.edu.

- Subhash Kak. Prajna Sutra. Baton Rouge. 2006.

- David Pingree. Picatrix: the Latin Version of the “Ghayat Al-hakim” (Latin). Warburg Institute. 1986.

- An English translation of Book 3 of the de Architectura by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio. http://penelope.uchicago.edu.