Contained within the Study of Silpa is the Sastra of Chitra. Continuing our Series on Classical Indic Art is the second installment. Today we cover Saastriya Chitra Sastra, more colloquially known as Classical Indic Painting.

Introduction

As our previous post on Classical Indic Art discussed, there is a lucid distinction between Fine Art (silpa) and Arts & Crafts (kalaa). Naturally, painting is often classed under both, despite the fact that its roots are as a fine art. Nevertheless, for consistency’s sake, since Silpa also refers to sculpture, it is best to avoid confusion & refer to painting as Chitra or Chitrakalaa.

Ancient dramas are replete with descriptions of not only pratimas but portraiture. The Prathimanataka and Viddhasalabhanjika are two such plays.

King Prasenajit from Kosala is said to have had a beautiful picture gallery in his Royal grove, with artwork from royals and commoners alike. Adi Sankaracharya mentions silpa as a pujavidhana, or legitimate manner of worship. [1, 17] King Bhoja from Dhar, declared it the first among all the fine arts. There is a long and unbroken history of aristocratic patronage of this finest of arts.

King Somesvara III Bhulokamalla born in the Kalyani Chalukya lineage described himself as chitra-vidya-virnachi (‘master of the art of drawing and painting’). His Abhilashitaartha-chintaamani, better known as Maanasollaasa, is an encyclopedic work with large sections dedicated to the Fine Arts (Silpa) and Performance Arts (Gandharva).

“The paintings of the Pandyan king and queen at Sittannavasal, Rajaraja Chola with his consorts at Tanjavur, Viranna & Virupanna at Lepakshi are telling examples of kings and noblemen re-sponsible for larger portrait murals.” [1, 3]

As such, the history of authentically Indic Art dates back millennia. While it may make for a nice narrative to stitch prehistoric art to that of the modern Indian man, the scope of this article will, true to form, focus on art drawing direct or indirect influence from the Sastras. But to properly acquaint oneself with Saastriya Chitra Sastra, one must understand its language.

Terminology

- Chitra Sastra—Study of Painting

- Chitra—Any Painted Object

- Ardha Chitra—Relief Painting

- Chitrabhaasha—A 1 dimensional Painting or Drawing

- Chitra Sutra—Standard text on Painting

- Chitrakalaa—Art of Painting

- Chitrakaara—Painter

- Chitrashaala—Paint Gallery

- Chitralakshana—Classification of Paintings

- Chitralankriti rachana vidhi—Mode of arranging paintings as decoration

- Chitradosha—Defects in painting

- Chitraguna—Merits in painting

- Chitragriha—Art house

- Chitramandapa—Picture platform

- Chitraphalaka—Picture board

- Chitrasutradana/Rekhapradana—Drawing the sketch

- Chitracharya—Eminent Authority on Painting

- Chitravidyopadhyaaya—Teacher of the art of painting & sculpting

- Chitronmilana—Infusing life into a picture

- Chitra Bhumibandhana—Canvas

- Chitrapata—Painting scroll

- Chitra lekhana/Varthika/Thoolika/Koorchaka—Paintbrush

- Samudgaka—Brush box

- Aviddhachitra —General study

- Rasa Chitra—Water colour

- Alakthaka—Red dye for feet

- Rekha—Line

- Rekhakarma—Delineation & Articulation of Form

- Raikhikha varthana—Line shading

- Thinduvarthi—Pencil for sketching

- Thorana-salabhanjika—Damsel under a sal tree, as bracket for ornamental gateway

- Viddha-salabhanjika—Portrait statuette

- Varthika—Paintbrush

- Varnaka—Determinant sketch

- Varnasamskaara/Rangasamskaara—Preparation of colour

- Varnikakaranda-samudgaka—Box full of colours

- Vithi/Oviyanilayam—Picture Pavilion

- Krtabandha—Mouldings

- Bhittichitra/Kudyaka—Wall painting/Mural

- Oordhvaka—Ceiling Mural

- Bhooshana—Decoration

- Bhoomika—Floor decoration

- Alpana/Rangaavali—Floor patterns

- Lekhya—Drawing & Sketching

- Lekhaneem—Pen

- Laavanya— Delineation of Beauty

- Kaalasthaana—Place of amusement or passtime

- Vinodasthaana—Passtime

- Lanchana—Emblem

- Laghu-likhita—Minimum of drawing that is the acme of skill

- Mandapa—Pillared Hall or platform

- Maangalyalekhya—Auspicious picture

- Nagaraka—Urban connoisseur

- Nithyavinodha—Perpetual entertainment

- Paada-peetha—Footstool

- Sikharakalasa—Steeple

- Silpa Sastra—Sculpture, Iconography, and Fine Arts in general

- Silpin—Sculptor, Iconographer, and Artist in general

- Prathima kalaa—Iconography/Image formation

- Prathima—Image/statuary

- Murthi—Religious Icon/Idol

- Rupa—Form/Image

- Rupakrithi—Of beautiful form

- Purnamurthi—Full effect of form

- Mudras—Hand gesture or Poses

- Thaalamana—System of measurement

- Thaala—Measure

- Vetradanda—Cane staff

- Sutikagriha—Childbirth apartment

Theoretical Foundations

As discussed in Sthaapatya Veda, the theoretical foundations of all Indic Art, including Chitra Sastra, are in the Veda.

Beyond this, there are numerous other tomes and treatises. Vishnudharmottara is considered the standard text on Classical Indic Art (Part III gives a full account on divisions, methods & ideals of chitrakalaa). Four others form the 5 main works on Chitra: Manasollasa, Aparajita-prccha, Samarangana-Sutradhaara, & Silpa Ratnam. There are others such as Sivatattvaratnaakara, and numerous works on Silpa specifically. Some like the Prajapatisilpa are now lost.

“The Vishnudharmottara covers several subjects like dance, music, prosody, grammar, architecture, sculpture, etc. Painting is also included therein. There is a great stress laid on the close relationship among fine arts like dance, music and art.” [1,5]

Interestingly, it provides a classification of painting as follows: satya (natural), vainika (lyrical), naagara (sophisticated), and mishra (mixed). The legendary origins of painting are attributed to Narayana who created Urvashi by drawing her on his thigh. He is said to have then taught this art to Vishvakarma.

Upon this edifice, a long tradition of Pauranic and saastric commentaries were developed. Chitra vidya is found not only in dedicated Sastras and Sutras on Silpa & Vaastu, but also in dramas and poems. Perhaps the Ratnavali of Sriharsa is the most famous work which touches on elements of Chitra. Lothario King Udayana notices the painting of Ratnavali and is smitten.

Regional artists have developed their own schools rooted in the classical tradition, and artisans and the masses have their own folk styles as well. But to understand the interrelationships between all of these, one must first study the key concepts.

Key Concepts

Indian #Art demands of the artist the power of communion with the soul of things, the sense of spiritual taking precedence of the sense of material beauty, and fidelity to the deeper vision within.#SriAurobindo #IntegralYoga pic.twitter.com/FpxFQrvp4O

— Sri Aurobindo (@integralyog) January 31, 2018

Shadanga

Rupabhedaah pramaanaani laavanyam bhaavayojanam |

Saadrsyam varnikabhanga iti chitram shadangakam ||

The fulcrum of Chitra Sastra centres around the concept of shadanga, or the 6 limbs of painting, as listed by Yasodhara above. These angas are rupabheda (variety of forms), pramana (proportion), lavanya yojana (creation of lustre & iridescence), bhava yojana (emotion infusion), sadrsya (likeness of portrayal), varnikabhanga (colour mixing). [1, 2]

Concepts such as foreshortening (kshayavriddhi), shading methods (patra, raikhika, binduja), and modes of representation were well known. Proportionality (pramaana), eye shapes (chapakara, matsyodara, utpalapatrabha), and poses ( sthaanas, such as rijvagata, ardhaju) were fundamental to chitra. Shapes of hair were also specified (kunthala, dakshinavarta, taranga, simhakesara). Nevertheless, symmetry was considered essential to an excellent piece of artwork. [1, 21]

According to the Vishnudharmottara, there are general guidelines for what is considered elegance in chitra:

“The line sketch, the most important, firmly and gracefully drawn, is considered the highest achievement by the masters rekham prasamsantyacharyah; there are others who consider shading and depiction of modelling as the best vartanam apare jaguh; feminine taste appreciates decoration in art striyo bhushanam incchanti; but the common taste is for the splendour and glory of colour varnadhyam itare janah.” [1, 2]

Related to the line sketch is the concept of Shading. Varthana (shading) has three varieties: binduja-varthana (stippling), patra-varthana (cross-hatching), and raikhika-varthana (fine-line shading). [1, 2]

“The best picture was with the minimum of drawing, api laghu likhiteyam drisyate purnamurtih” [1, 2]

Upon this foundation, various types of paintings developed.

Painting Types

The Maanasollasa lists 5 types of paintings:

Viddhachitra—Portraits or Still lifes. These are realistic or exact copies.

Aviddhachitra—General study. Merely resemblances. What impressionism is to realism.

Bhaavachitra—Expresses various rasas. Emotion expressed prioritised over resemblance

Rasachitra—Coloured solution (drava). Similar to water colours. Kolam is included here.

Dhoolichitra—Characterised by bright colours.

It is important to note here that Chitra in general refers to any painted article (including sculptures or metal objects). A figure in relief (high or low) is termed ardhachitra. A true painting, therefore, is termed chitrabhaasha.

Portraiture was itself a process. Experimental sketches (hastalekha) were drawn as a preliminary exercise followed by a final varnaka, or determinant sketch. The whole process was known was chitrasutradana. The colourisation of the final outline would infuse life in the work, a stage known as chitronmilana. [1, 17]

But no painting was possible without a proper brush.

Brush types

Varthika was an implement used to apply the or plaster paint onto a surface. They were sketching sticks or crayons, made from the sweet-smelling root khachora, which was mixed with boiled rice, and rolled to a stump. Brick powder and other agents were often added as well.

As for paintbrushes proper, the tiny tulika was made from a thin bamboo rod attached with a copper pin and feather. Soft animal hair mixed with lac (wax) made the standard brush. The largest was the koorchaka. It should be noted that the tulika, or salaka, was utilised for unmilana, which was the final touch, where the eyes of a figure were opened.

Subjects were painted not only on canvas (patta), but also on walls (murals being known as kudyaka or bhittichitra).

Medium

Brick plaster, clay plaster, and ointment are the main media used as primary agents, called Lepya. Lepyakarma refers to their preparation, which can often be very detailed. [1, 407] The two main types of ointments are sudhaa-bandhana (made from white stone pebbles & bilva liquid) and mrttika-bandhana (a concoction of butter, milk, atasi flower, barley powder, wheat grains, milky tree bark, guda-samyuta bakula, and Indravrksa). [1, 409]

In general, paint colours (ranga or varna) were made from mineral agents.

Colours

Colours in Chitra Sastra are have 2 classifications types, 1 from the Manasollasa and the other from the Vishnudharmottara. The Pure colours (suddharanga) listed by the first are 4 in number (red, white, black, and green). The Primary colours (Moolaranga), per the second, are listed as follows:

Gairika (red), neeli (blue), suddha/svetha (white), kajjala (black), haritala (ochre yellow). These were then followed by the secondary colours (antarita) or compound colours (misravarna). Alternately gaura is often used for fair (reddish white). Red seems have the most numerous gradations or shades:

“The Silparatna gives three gradations of red Sindoora for light red, Gairika (mountain-born) red (mineral chalks) for a middle tint and Laaksa (lac) juice for a deep colour.” [3, 412] Elsewhere, however, we see other descriptions, pale red (dhoomracchaaya) from conch powder and red mountain chalk, Darada (vermillion), Dhosara (tawny), and alakthaka (red dye).

Indigo was used for blue and turmeric for yellow. Metallic agents were also employed: kanaka (gold), rajatha (silver), thaamra (copper), traapusa (tin), abhrak (mica), & loha (iron). [3, 417]

Vajralepa and nirjasakalka were animal and vegetable binding agents for colours. [1, 19] A big brush, koorchaka, was used with a wash (akshalana). [3]

Andhaka Thaala

Andhaka-pramaana is an foundational aspect of portraiture. Andhaka is a model that allows an artist to determine measurements (thaala) and proportions(pramaana). It is an index that is used as a reference point. Mukhandaka, Vrttandaka, and Alasandaka are the preliminaries. Body dimensions (kaayaa-pramana) are a separate consideration. Male figures are classified as hamsa, bhadra, malavya, ruchaka and sasaka, along with their Female counterparts. These categorisations determined the body dimensions of the subject.

Why was so much emphasis placed upon correct measurement? Here was the belief behind this, especially regarding religious iconography:

Even when (duly) invoked by the best of Brahmins, the gods never enter images short of (Saastric) measurements and devoid of the marks (laksanas of divine form); (but) demons, ghosts and hobgoblins always enter into them, and so a great care should be taken to avoid shortness of measurements, (An image) possessed of all the beautiful marks is said to be excellent from every point of view. [3, 403]

Maharishi Markandeya goes on to say this in the Vishnu Purana:

“Blessed is a work of art (endowed) with all (the Saastric) marks, (as it brings luck ) to the country, to the king and the maker, (and is as the gods) long for it. An image, there-fore, should be properly made by all men with great care, (endowed) with all (the Saastric) marks.” [3, 403]

Related to this is the concept of plumb lines. These are 3 in number: brahmasutra (runs from the forehead middle hairline (Kesanta) to the feet), and the 2 pakasutras (start from either ear, pass through the chin, and run to the feet). [1, 403]

Plumb lines lead in to the next key concept.

Sthaana

- Rijju/Rijvagata—Straight pose

- Anrijju—Not straight

- Ardhavilochana—Side view

- Pristhagata/Paravritta—Back view

- Sachikrita—Nearly side view

- Sanakriti—Globular

- Parsvagata—Side view

- Pristhavastika—Legs crossed till back

- Maharajaleela—Seated at east with hand resting on knee

These are the main stances used for subjects in Chitra Sastra. They are determined by both angular considerations (front and sidelines) as well as measurements (in angula). While the Manasollasa gives only five such “attitudes”, these stances are more comprehensive and collected from several other commentaries. [3, 404]

Chitrashaala

The Naradasilpa has a chapter dedicated to the chitrashaala. While silpashaalas are more generic art houses, chitrashaalas are specifically dedicated as galleries of painting. While all types of paintings could be shown at temples, only those representing sringara, hasya and shaantha could be shown in private residences, especially the King’s residence. Bhavasabalata, the confluence of emotions, can often occur.

Sayana-chitrashaala

These are galleries of Princesses who established an art annex next to their sleeping apartments. It was believed that looking at an auspicious object whence waking up would bring auspiciousness throughout the day.

Abhisheka-chitrashaalikas

These are galleries adjacent to bathing apartments.

Guhya-chitrashaala

These were private galleries, typically at the residence of the well-to-do. These included not only wealthy merchants, but also courtesans and the less respected classes of society. Socialites such as vitas (courtiers), dhurtas (rakes), and chetas (sycophants), were frequenters of such places, along with patrons of these women who lived by their beauty. [1, 10]

Dedicated institutions were known as vithis, and rows of such mansions referred to as vimanapankhti. These public galleries were often massive, and had ornamental doorways & balconies, massive pillars, and gopuras. They were perfumed, and were open in the evenings for visitors to pass their time, or for lovers to congregate.

“The Naradasilpa prefers the chitrasala to be located at a junction of four roads, opposite a temple or royal palace, or in the centre of the king’s highway; it could be drum-shaped or circular in plan, and have a verandah, a small hall, a main central hall and side halls with stairs leading to the upper storey. It would be supported by 16, 20 or 32 pillars, have several windows, an ornamental canopy” and many other such structures and fixtures. Chandeliers and mirrors were afforded prime of place to illuminate halls. [1, 10]

Themes

There were a variety of themes and motifs in ancient Indic artwork. As can be seen today, much of it was devotional, but much of it more material. Romantic scenes between apsaras and their paramours, as well as scenes with nagas, devas, asuras, yakshas, kinnaras, and garudas were all commonplace. Nature scenes were also commonplace with pashu (beasts) and pakshi (birds) being favourite motifs.

Regarding day-to-day life, beyond the nobility and its pervasive hunting scenes, one finds the prasaadhika (attendant) and pratihari (usher) often featuring. Nevertheless, the most celebrated themes were Rasaleela (folk dance in a circle), Panagosthi (drinking bout), and Jalakreeda (water sports). [1,11]

These themes could be done in Prakritika (folk style), discussed further below, as well as Sanskritika (classical style). Finally, Patras styles of painting delineated natural scenery, especially of a region. They were landscapes of sorts, and were typically dedicated to specific aspects (i.e. sun, moon, forest, season) that would be evoked in the chitra by the chitrakaara. [3, 438]

The Painter

“It is the most difficult art and can be finely executed only by a painter not only expert in hands – the craftsmanship, but also fully drunk in nectar of divine intuition. Painting is as much a saadhana as Music, both requiring an exercise of mind and body” [3, 443]

The chitrakaara has a fabled history in Bharatavarsha. Arguably the most famous was in fact a woman. The Love Story of Usha & Aniruddha is well-known to most rooted cosmopolitans. It was the friend and confidante of Usha, the aptly named Chitralekha, who was able to delineate the eminent Kings & Princes of the age to determine exactly whom was the literal man of her dreams.

There is another less legendary and more historical one dating to the second century BC inscription, in a Ramgarh cave. It takes note of a rupataka and his danseuse sweetheart.

“As art permeated life in ancient India, every young man and woman of taste had a knowledge of art, dance and music as esssential factors of literary aesthetic education. The non-professional artists, with enough knowl-edge adequately to appreciate art trends in the country, were in abundance and judged the art of the professionals.” [1,12]

Pass times, vinodasthana, were numerous in ancient India, and it is only natural that the fine arts feature prominently. An urbanite of taste, nagaraka, was expected to have cultivated his skill at painting, with a dedicate room to the arts. This would feature a veena hanging overhead, a paintboard (chitraphalaka) and box full of brushes (varthika-samudgaka).

Chitrakaaras were however professional, while the amateurs were dindins. Above either were the chitracharyas famed for their hastochchaya (good hand). Dindinas were castigated for ruining pictures through darkening touch ups and violating the original lustre of colours through dabbing, while Chitracharyas could repair them effectively.

The Uttararamacharita mentions a chitrakaara named Arjuna, who painted Rama’s journey, in the palace. These masters of the brush were invited to special occasions such as royal marriages and accorded respect, particularly when commissioned to do work.

“Painting being a fine art, is ornament of a town, hobby of townsmen and a civilized trait of citizenship. That every cultured man had in his house a drawing board and a vessel for holding brushes and other requisites of painting, is corroborated” [3, 383]

Schools of Bharatiya Chitrakalaa

19th century Mysore style painting of Mahishasuramardhini, unfortunately sold at a antique shop in Mumbai pic.twitter.com/XoZWrJvBIs

— aryabhatti (@aryabhatti) January 8, 2016

The ancient work, Aparaajita-prccha, gives 6 styles of Chitrakalaa (Naagara, Draavida, Vesara, Kalinga, Yamuna, and Vyantara). Over the years, however, many different styles and schools have emerged. [3, 370]

To map all the schools of Bharatiya Chitrakalaa would be an expansive and imposing task, particularly when telling the truth is the top priority. Historical paradigms aside, there are nevertheless some nostrums which must be accepted in the present period. These are that Sastra is the fount from which these various schools spring forth or are inspired from.

Next, is that truly Indic schools are not just attached to the landscape by happenstance, but also by spirit. Finally, that freedom and creativity within the guidelines of sastra allowed the various desi schools to flourish and build upon the core. No doubt, foreign inspiration was there from time to time, especially in the latter periods, but syncretism should not be pretext through which the native is subsumed by the foreign. As such, here is a listing of the truly Classical Indic Schools of Chitrathat are major in achievement and Bharatiya in spirit.

Amaravati

Amaravati may be on the Eastern ghats, rather than the Western ghats of Ajanta, yet its influence spread far and wide. This school is most closely associated with the Satavahanas. The paintings and sculptures of the early period of the Ajanta align with the Amaravati silpas. They also correspond to other Satavahana sites such as Jaggayyapeta.

Recently the Bedsa cave dated to the same period features fragments of painting with a damsel as its subject. The ekavali she wears recalls Amaravati and Karla. [1, 27]

Gupta

6.77)"(Like the special appeal of art of Ajanta springs from the remarkably inward,spiritual,psychic turn given to its conception & method)" pic.twitter.com/JfPBtNsYeC

— Mohit Bansal (@Auro_Mere) January 27, 2017

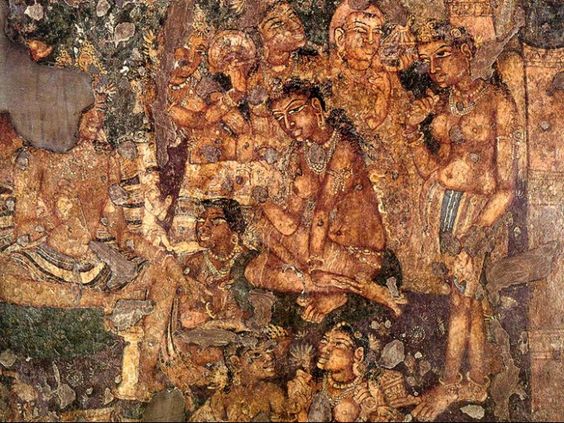

“Some of the artificial caves dedicated to religious purposes, however, give us samples of the work of highly developed schools of painting, and few would dispute that the murals of Ajanta are among the greatest surviving paintings of any ancient civilization.” [5, 377]

The most celebrated of all of India’s paintings, the ardhachitra featured at Ajanta is among the finest in the world. Rather than a school in and of itself, Ajanta is the product of many generations of contributions. The earliest pieces at Ajanta date back to the Satavahana era, such as the famed reconstruction of the ‘Andhra Princess’ featured above. It is under the later Gupta dynasty that we see the this romantic and serene guhashaala (in the truest sense) come into its own. It features themes primarily from the Buddhist Jatakas.

Ultramarine remains the most vibrant of the colours used here. With a total of 22 caves, Ajanta is an artistic wonder of the world. Though under the official rule of the Vakatakas, due to the regency of Princess Prabhavati Gupta, it was thought to be a virtual extension of the Pataliputra imperium.

Further, it demonstrates many of the same techniques applied at Bagh (near Gwalior) as well as Sigiriya in Sri Lanka, thought to be contemporaneous.

Nevertheless, an inscription has been found mentioning a section of Ajanta being dedicated by Varahadeva, minister of the Vakataka King Harishena. [1, 41]The walls of Ajanta were covered with a coating of clay and white gypsum. Though there has been flaking, after millennia, it has kept well considering the climate. The paint pigment used remains striking. One can only imagine the lustre of the original state. [5, 377]

In 1930, Laurence Binyon, Director of the British Museum, wrote: “Whoever studies the art of China and Japan, at whatever point he begins, starts on a long road which will lead him ultimately to Ajanta.” Scholars in all Asian countries trace the roots of their classic paintings to the murals of India.[10]

Bhanja

Visit #Sitabinji of #Keonjhar District, a place that is famous for its #FrescoPainting. http://t.co/tI7xtRGobd pic.twitter.com/yidW73KAbG

— Visakha Travels (@VisakhaTravels) August 17, 2015

Following the Gupta paramountcy, a precursor to the Palas, the Bhanja school of Odisha is worthy of mention as well. Though an obscure name to most, this Odia dynasty is known for the Kalinga king Maharaja Disabhanja. Dating back to the 8th century CE, the collection of murals at Sitabhinji in Keonjhar district is the earliest remaining artifacts of Odia chitra. It features a 17 x 10 mural of a royal procession, replete with a king on elephant back, escorted by cavaliers.

Pallava

The Kailasanatha temple at Kanchi is of great antiquity. This rock-cut structure is attributed to the Pallava King Rajasimha, who was assisted in this artistic endeavour by his Queen Rangapataka.

“The paintings in the monuments of this king give us splendid examples, though not many, of the Pallava phase of painting” [1, 52]

Panamalai (with an exquisite Parvati mural) also provides us with lovely examples of this artistic phase. Fading though they are, these murals nevertheless, are superbly designed. They give glimpses into the level of mastery that must of have been reached by ancient Bharatiyas. With an identifiable style of line and colour in cave temples, such as the one at Mamandur, these successors to the Satavahanas made their mark on the art of Tamil Nadu.

Chalukya

The Chalukyas were a great imperial dynasty with a tremendous impact on the literature and art of the Dakshinapatha. Due the interregnum of the Rashtrakutas (a collateral branch of the Chalukyas) being capped by the Western Chalukyas of Kalyani, the rise-fall-rise of the Chalukyas can be treated as one spectrum of art.

While the third phase of Ajanta paintings are attributed to the early Chalukyas, other sites such as Vatapi (Karnataka) and Ellora are credited to them as well. The Chalukya style no doubt spread west, to Gujarat for example, where an offshoot dynasty long established itself. Lovely specimens of chitrabhaasa are to be found in Jaina illustrations there, such as the well-known Jain Kalpasutra manuscript.

The Rashtrakuta chitra contribution is best characterised by the specimens of ardhachitra at Ellora.

Chola

One of the most spectacular and best preserved collection of paintings can be found at the Brihadeeshvara Temple, in Thanjavur. Credited to Emperor Rajendra Chola, it features very detailed delineations that are devotional in nature. Though there are fragments of early Chola paintings at Narthamalai and Malaydipatti (among others), it is at this temple endowed by the great Thalassocratic sovereign of Tamil Nadu that we see this school in all its Thousand year glory.

Rajendra managed to exceed his father not just in military might but in artistic endearvour. Nevertheless, it is of his predecessor that an actual portrait survives.

Called Nityavinoda (demonstrating his taste in art), Rajaraja is considered the greatest of the Chola line, and he endowed a temple of Lord Shiva at Rajarajeshvaramudayar. [1, 63]

Pala

The Pala Empire of Bengal reached its highwater mark with Dharmapala. At the height of their power, these emperors of the East did a veritable digvijay of Bharatavarsha, but were ultimately humbled only by the Southern Rashtrakutas.

Regardless, this regal Buddhist dynasty would define the art of Bengal for centuries. Due to the onslaught of foreign invasion, most of what survives is in recovered palm leaf manuscripts. The Prajnaparamita manuscript from the reign of King Mahipala is arguably the most significant.

Images in metal work from Kurkihar and Nalanda also stand out, as do some samples from Sundarbans, found in local museums today.

Vijayanagara

There were many streams in the confluence of Vijayanagara, some of which can be treated as their own schools. These include the Kakatiyas from Telangana, the Hoysalas from Karnataka, and the Pandyas from Tamil Nadu. The Kakatiya painting contribution can be found at Pillalamarri and Tripurantakam, the Hoysala at Moodbidri (in palm leaf manuscripts), and the Pandya at Thirumalaipuram & Sittannavasal (known for its Jain art). [1, 57]

Regardless, the Rayas of Vijayanagari soon evolved their own style, noted for angular features and ochre colours, which would colour the annals of the City of Victory.

Specimens of Vijayanagara chitrakalaa can also be found at Tirupati, Chidambaram, Tadpatri, Kanchipuram, Kalahasti, and Tiruvannamali.

However the most impressive specimens of the Vijayanagara school are at Lepakshi.

While Ajanta and Amaravati enjoy greater notoriety for their ancient Andhra/Andhra-inspired Art, Lepakshi is a standout for the late medieval period.

Most of the paintings at Lepakshi are damaged, and some erased by the passage of history. Nevertheless, there remains a substantial collection to showcase how this site is truly a cultural gem.

“enough remains to show what considerable mastery the painters had attained over brush and colour and how well their mind worked in creating panels of charming portraits, the stories of Sivalila (Pl.12), the coronation of Rama, Arjuna fighting Kirata, Krishna as Vatapatrasayi and so forth.” [1, 77] Among the other specimens are the murals of the Bhikshatana, Kalari, Gangadhara (Fig.9) and Tripurantaka, which are considered to be dramatic and original in concept.” [1, 77]

“the 24 by 14 ft fresco of Veerabhadra on the ceiling before the main sanctum sanctorum is the largest in India of any single figure. ” [2]

“Parvati with her companions, Lepakshi, Andhra Pradesh, 16th century. This lively paintings reflects the cosmopolitan culture of the Vijayanagar empire. The rich and varied textiles are remarkable. The angular features and protruding eye exhibit the pan-Indian medieval traditions of painting.” [10]

Nayak

While the Vijayanagara empire continued for more than half a century after the Fall of The City, the centre of gravity was steadily shifting to the successor states. These Telugu Nayak kingdoms eventually enjoyed independence, and ruled sovereignties in Tamil Nadu. Meenakshi & Alaghar at Madurai, and Tenkasi Sankaranarana kovil and Perur are all symbols of the contributions of these survivors of Talikota. Their art dominated the Tamil region in the 17th and early 18th centuries. The two main branches of this school were Thanjavur and Madurai.

Thanjavur

Raghunatha Nayak’s contributions at Thanjavur and Kumbakonam are well known. Along with adding to the extant contribution of the Chola Emperors, the Thanjavur Nayaks added their own panels. The Maratha Empire would later take over from these Vijayanagara offshoots. This period also provides a branching point for strains of modernism making their way through contact with European colonialists.

Madurai

Tirumala Nayak was an highly reputed patron of the arts. The sixty four lilas of Shiva are memorialised at the Meenakshi temple. These and others are credited to the masters of Madurai.

Rajput

“The use of orpiment in Jaipur painting and Rajput painting as such only reminds us that the Rajput school, though greatly influenced by the Mughal school retained some of the earli[e]r traditions intact.” [3, 415]

In fact, this is the main schism that defines the Rajput tradition (both historically and artistically). The Jaipur style betrays Mughlai persianate influence due to its proximity to the Delhi court. In contrast, Udaipur upholds the native spirit via its irrepressible pride in the folk tradition of Rajasthan. The Rajput style spread wide out of this romantic desert land (including branches at Bikaner & Jodhpur), and reached north to Kangra and east to Bundi, where the Baramasa format become popular.

Baramasa paintings are a distinct style of miniatures that developed under Rajput patronage. Literally meaning 12 months, 1 painting for each month is created. More folk than classical in nature, it is rustic in both inspiration and popular in its implementation.

While epic themes feature prominently in Rajput paintings, it remains rooted in the land as well. Rajasthan’s pastoral people are given prominence in paintings, and it is as much the chitra of the Ranas and Rawals as it is of the ryot. Classical in implementation, it is often folk in spirit.

The Rajput school is, at present, credited to Sringaadhara from Marwar, born in the reign of King Sila. He is considered the principal artist who engendered the style for which Rajputana chitra is traditionally known. King Sila is thought to be the 7th century Shiladitya Guhila of Mewar. As such, rather than Jaipur being the launching point for the Rajput style, it was quite the reverse. It is in Udaipur that patronage for and preservation of authentic Rajputana is found. [3, 442]

“Rajputana Painting, is essentially Hindu in expression, and in many aspects demonstrates that it is the indigenous art of India, a direct descendant of the classic frescoes of Ajanta.” [3, 467]

Nevertheless, there is a third branch that is often classed with the Rajput style that in reality launches into its own school.

Pahari

Branches of the Pahari school include Kangra, Guler, Garhwal, Basohli, & Chamba. Kullu and Jammu are both often included as associates. Pahari painting, as embodied by the Kangra branch, is characterised by the use of azure. [3, 415]

“Pahari painting does not denote great inspiration or display any decided expression of thought or feeling. It is an art of patient labour and naive devotion. Its chief features are delicacy of line, brilliancy of colour and minutness of decorative detail.” [3, 469]

Romantic themes are prominent at Kangra, and here Nayaka is used in the classical sense of Romantic heroes. Themes from Purana and Tantra figure prominently.

A number of portraits of Pahari Potentates also survive to this day. Characteristics of Pahari painting include clean delineations and palpable brushwork.

Kerala

Without a doubt, the first name that comes to mind when one thinks of Kerala Art or even modern Hindu Art, is Raja Ravi Varma. He undoubtedly embodies best the various veins of modernism that made its way into colonial India. But before this Travancore royal made his mark, Kerala had a previous doyen in Srikumara. Given generous patronage by King Devanarayana of Travancore, he composed the work Silpa Ratnam that remains a gem to this day.

It should be noted here that Kerala painting dates as far back as the Cheras of the 8th century (if not earlier). The cave temple at Thirunanthikkarai (now in Tamil Nadu) features a lovely face in classical style. [1, 58]

Folk

No account of Indic art would be complete without mention of some of the folk traditions of painting prominent throughout India. Perhaps the most popular is the artful and playful Madhubani school of Bihar.

Madhubani

Very down to earth and easily accessible to art aficionados of all types, this school of art is folksy in spirit yet epic in orientation. Even the origins are traced back to one of Mithila‘s most famous figures (King Janaka), making it Mithilanchal’s most treasured art.

Though simple in design and execution, Madhubani is known by the wide features of its figures and the detail in patterns.

Patachitra

Although Patachitra is quite clearly an all-India sanskrit term (‘cloth painting’), it has at present, become distinctly associated with the eastern state of Odisha. With its pastoral themes and lovely borders, it has become literally wearable art.

The style is easily identifiable and has become a souvenir of sorts for travelers to the state.

Kalamkari

Related to Patachitra, is its southern neighbour of Kalamkari. This art of Andhra obviously evolved as part of the native folk tradition. It branched off from its Odia counterpart in name, due to the rise of the Golkonda state, giving it the persianised kalam kari. Interestingly enough, Vijayanagara’s influence is evident among Golkonda & its 4 sister states [1, 99]

Either way, its patachitra roots are obvious. Although some of its implementations deal with Turkic themes, the general spirit remains Telugu in essence.

As mentioned above, there are a number of artists and even schools outright influenced by modernism, and now post-modernism. However, these topics are outside the scope of the present article, which is focused more on the organically native Classical Tradition.

Important Texts

Silpa Sastra

Vishnudharmottara Purana

Samyuttanikaaya

Aparajita-prccha

Samaranga-sutradhaara

Manasollasa

Silpa Ratna of Srikumara

Agastya-Sakaladhikara

Chitra lakshana of Nagnajit

Naradasilpa

Sarasvatisilpa

Prajapatisilpa

Kasyapiya-Amsumad-bheda

Maanasaara

Balagopalastuti

Siva-tattva-ratnakara of Basava Raja (17th Century)

Sarasvati-chitra-karma-sastra

Personalities

“The Indian painter, like the sculptor, usually dedicated himself to his art. He made it an offering to the divine spirit and personally obscured himself. The result has been that most names of artists in India are lost in oblivion.” [1, 17]

Nevertheless, a few names have come down to us in the present time.

Narayana

Naga Raja Nagnajit

Maharishi Markandeya

Arjuna from Ayodhya

Kumaradatta from Pratishthana

Bimbisara from Magadha

Paramara Bhoja

Chalukya Somesvara III

Sivasvamin, Chitracharya

Sringaadhara from Marwar

Dhiman & Bitpalo (father and son from Pala Bengal)

Srikumara from Travancore

Raja Ravi Varma

Conclusion

Please save Treasure trove of old Tanjore paintings in neglect at EttukaalMandapa in Gandarvakottai TN.See article: https://t.co/yyqurUNEU4 pic.twitter.com/FyEn2efNAC

— aryabhatti (@aryabhatti) December 29, 2016

Perhaps what is most prominent about Classical Indic Painting is its interconnected-ness with other disciplines. This is seen not only in the matryoshka doll type classical connection of Sthaapatya → Vaastu → Silpa → Chitra, but elsewhere as well.

“Markandeya: Without a knowledge of the art of dancing, the rules of painting are very difficult to be understood. Hence no work of (this) earth (oh) King should be done even with the help of those two, (for something more has to be known” [3, 433]

“Markandeya said: The practice of (dancing) is difficult to be under-stood by one who is not acquainted with music. Without music dancing cannot exist at all“. [3, 433]

What is the reason for painting and dancing to be so interlaced? According to the Vishnudharmottara, Chitra is considered as much the art of imitation (anukarana) as Natya is. [3, 434] Aesthetics, of course, are prominent in both as this accomplished danseuse explains here. In the case of painting, from rasa, springs forth rasa-drsti.

Though referred to as the nava rasa, 2 more have accumulated over the ages, bringing the total to 11 (sringara, haasya, bhayaanika, bibhatsa, karuna, raudra, veera, adbutha, shaantha, vatsalya, & bhakti ). Attached to them are rasa-drstis, which are sentiment-glances communicating the overarching rasa desired. They are 18 (or 20) in number (lalitha, hrsta, vikasita, vikrta, bhrkuti, vibhrama, sankuchita, urdhvagata, yogini, dina, drsta, vihvala, sankita, kunchita, jihma, madhyastha, sthira, vipluta, vikortha, & madira) with a number attached to the same rasa.

Vaamanabhatta compared drama (nataka) to picture (rupa) in his Kaavyaalankaara-sutra. In fact, he specifically states this is why a dramatic composition is called rupaka. [3. 435]

It should also be noted that, contrary to conventional wisdom, calligraphy of a high level was also practiced in Ancient India. “A scribe, who was a contemporary of the Western Chalukya king, Vikramditya VI, boasts of his skill in arranging beautiful letters in artistic form, entwin-ing into them shapes of birds and animals.” [1, 14]

Chitrakalaa Today

The so-called “elites” of modern India would do well to learn from the nobility of old, which generously commissioned artwork by professional painters. If chitrakalaa, true bharatiya chitrakalaa, is to be revived, then rather than giving patronage to foreign tastes and artistes that patronise them, they must support local artists and artisans to revive classical Indic painting. What is the point of all that money if you don’t have taste? Perhaps there is a lesson here for New India’s nouveau riche:

Hindu Kings built temples, lakes and ponds instead of courts and jails. They built roads, guesthouses. They planted trees. They encouraged art & culture.#Periyava

— Sage of Kanchi (@haraharasankara) November 21, 2017

“Literary reference alone would prove that painting was a very highly developed art in ancient India. Palaces and the homes of the rich were adorned with beautiful murals, and smaller paintings were made on prepared boards. Not only were there professional arts, but many men and women of the educated classes could ably handle a brush.” [5, 376]

If the artists of old thrived and spread their art Northwest and East, it is because chitrakaaras received patronage from the movers and shakers of their millennium. What is considered fashionable at present hardly holds a candle to what was practiced in the past.

“The dry sands of Central Asia have preserved paintings which, though not strictly Indian, owe much to Indian inspiration…The many murals and paintings on boards found at sites in Chinese Turkistan and other parts of Central Asia are mostly somewhat later, and who greater deviation from Indian models, though their debt to India is quite evident. They date from a period when the trade route to Chine was wide open, and give proof of the debt which Chinese art, despite its very individual character, owes to India.” [5, 379]

Paintings of late YG Srimati of Mysore.

So elegant.

why don't we hear more of such artists?

MF Hussein couldn't paint like to save his life pic.twitter.com/YXsqDH8WNx— aryabhatti (@aryabhatti) November 7, 2017

Perhaps the emphasis of this authentic elegance is what is missing today. The etic lens has percolated from indology into the arts themselves. Such a reality is all the more the tragedy given the promise of the emic:

Indian art, be it painting or music, architecture or sculpture, is a class by itself. India’s culture being more spiritualistic than material-istic, naturally all her arts are imbedded in its philosophy. Indian artist is a philosopher first and artist afterwards. [3, 444]

The greatness of Indian #art is the greatness of all Indian thought and achievement.#SriAurobindo #IntegralYoga pic.twitter.com/d1m0jUrWa7

— Sri Aurobindo (@integralyog) November 28, 2017

References:

- Sivamurti, C. Indian Painting. New Delhi: National Book Trust.2013

- Kumar, Pushpendra Ed. Silpa-Sastram. Delhi: Eastern Book Linkers.2006

- Shukla, D.N. Vastu-Sastra (Vol.II): Hindu Canons of Iconography and Painting. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. 2003

- Shukla, Lalit Kumar. A Study of Hindu Art and Architecture (with special reference to the terminology). Chowkhamba. 1972

- Basham, A.L. The Wonder that was India. New Delhi: Rupa & Co. 1999

- Dabhade, Shrikant B. The Technique of Wall Painting in Ancient India. Malkapur: Arun Printing Press. 1973

- S, Nayanthara. The World of Indian Murals and Paintings. Chilibreeze. 2006

- Charak, Sukhdev Singh & Anita K. Billiwaria. Pahāṛi Styles of Indian Murals. New Delhi: Abhinav Publ. 1998

- http://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/travel/The-hanging-pillar-and-other-wonders-of-Lepakshi/article13383179.ece

- http://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl2021/stories/20031024000107000.htm