Introduction

Part-1 traced the western history of the antidote-poison pair of Bezoar & Wolfsbane, recognizing the duo as a marker of knowledge transmission from India to Europe.

This transfer initially occurred through Arab/Persian sources and later by direct appropriation. A preliminary study reveals a trail of reductive translations of Vedic concepts like Bandhuta and subsequent digestion into European ‘pagan’ traditions and Renaissance expression.

This concluding part studies the Indian provenance and Vedic basis of toxicology and antidotes. We find the antidote-poison pair mentioned in the most ancient Indic texts. The content is divided into four subtopics. Readers can skip ahead to a subtopic using the page jumps below.

A Question of Etymology

Al-Beruni’s 10th-11th century description [6] mentions the primary source of Bezoar stones as India and then China and states that “Some through apocopation and orthographic error called it hajar al-bīsh. But this orthographic error is very true, correct and noble, since it is a theriac for aconite poisoning.’

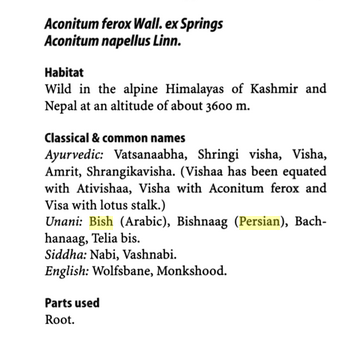

Bīsh (beesh) is the ancient Arabic/Persian term for Wolfsbane, i.e. the Indian Aconite plant Vatsanabha [7]. This name is derived from Vatsa (calf) and Nabhi (umbilicus) based on the shape of its tuber [1]. Bīsh is a corruption of the Sanskrit Visha.

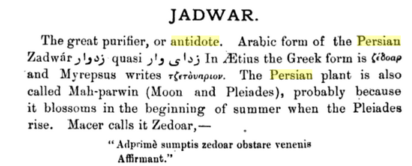

The ancient Arabs and Persians hailed a plant (Nirvishi) found in India and China as an ‘ultimate purifier’ and antidote to Bīsh and called it Jadwar/Zadwar [8, 19], which became Zedoar/Zedoare in Europe.

“The history of this drug is beset with many difficulties, on account of the vague meaning of the term Jadwar; the name by which it is generally known, and which appears properly to mean the great antidote. Under Jadwar, the author of the Makhzan-el-Adwiya gives Antila as the Arabic name, and Saturyus as the Greek. Speaking of Bish he says that the Hindus suppose that the only plant which can grow near it is the Jadwar, which is an antidote to it, and that they also affirm that there is a kind of rat, called ‘Bish mush bisha,’ which lives upon Jadwar, and is an antidote to Bish ; this is the Buka Bish Mush of Ibn Sina.“.

An Indian reader may guess that ‘Bish Mush Bisha’ is from Visha-Mushika. In these descriptions, Bish-Jadwar are viewed as polar-opposite twins growing side-by-side. If Al-Beruni was comparing the Bezoar to Jadwar, then a portmanteau of Bīsh–Jadwar yields another meaningful reconstruction.

There once was a Dormouse who lived in a bed Of delphiniums (blue) and geraniums (red) And all the day long he'd a wonderful view Of geraniums (red) and delphiniums (blue)... " - The Dormouse and the Doctor, A.A. Milne.

It is worth noting the near-complete absence of Ayurvedic references in these colonial journals that continued to cite Arab/Persian texts that translated Hindu findings. If they had looked into the original texts, they would have benefited from an authentic, first-principles understanding of antidotes and toxins in Ayurveda. It is only when we examine the original Sanskrit names that we begin to appreciate the different dimensions of these plants [4].

Ayurvedic Roots

For brevity, two references provide the necessary background for answering queries on Ayurveda specific to this post: The ICP series on Ayurveda explains its origin, objectives, terminology, concepts, personalities, main texts, impact, and history [3].

https://indicportal.orgclassical-indic-medicine-i-ayurveda/

A brief but valuable review of ancient Indic medicine by the Centre for Policy studies (CPS) [2] specifically addresses the question of epistemology.

The Ayurvedic knowledge system is based on the Vedic principle of correspondences (see Part-1) and Unity of Consciousness [4]. These principles are central to the ancient Charaka Samhita. The Sharira Sthana section of this Samhita contains a chapter Mahatigarbhavakranti Sharira that explains the ancient Indic ideas of embryology:

एवमयं लोकसम्मितः पुरुषः|

यावन्तो हि लोके मूर्तिमन्तो भावविशेषास्तावन्तः पुरुषे, यावन्तः पुरुषे तावन्तो लोके इति; बुधास्त्वेवं द्रष्टुमिच्छन्ति||१३||

“Therefore the individual is an embodiment of the universe. All the material and spiritual phenomena of the universe are present in the individual and vice versa. This is how the wise desires to perceive.” [1].

Maharishi Charaka. Photo by Alokprasad,Balajijagadesh – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

The Purusa Vichaya Sharira chapter in the same section dives deep into the nature of Purusa, the integral human being and explains the importance of practically applying these Vedic concepts in the context of healthcare and medicine. Any healthcare system that deletes these guiding principles rooted in Satya, Rta, and Dharma will become increasingly fragile and unsustainable.

सर्वलोकमात्मन्यात्मानं च सर्वलोके सममनुपश्यतः सत्या बुद्धिः समुत्पद्यते "seeing the universe in the purusha, and vice-versa, gives rise to true knowledge" [1].

This Samhita is an important and highly accessible work but is not the ‘first text’ of Indic medicine, which originates in the Vedas. Translated keywords from the Samhita were selectively quoted in the western medical literature after Abhinash Chandra Kaviratna’s English translation of the Charaka Samhita [11] was published in 1890. Kaviratna notes how Indic medicine has stood the test of time and influenced different civilizations:

“Professor Wilson is of opinion that the Arabians of the eighth century cultivated the Hindu works on Medicine before those of the Greeks; and that Charaka and Sushruta, and the treatise called Nidåna, and others, were translated and studied by the Arabians in the days of Haruh and Mansur (A.D. 775) ..

The reader will find that some of the highest and latest discoveries of hygienic science were well known to the ancient medical authorities of India …

..Many persons who have enquired into the matter, without yielding to the prejudices fostered by Western culture, are of opinion that many diseases peculiar to India can be cured more effectually, cheaply, and quickly, by aid of intelligent native practitioner relying on Charaka than by pursuing Western systems of cure.“

The scope of this Samhita is huge as the CPS study [2] notes: “… the canonical medical texts describe 600 to 700 drug plants with their different parts forming different drugs, 165 varieties of animals again with different products and parts acting as different drugs, and 64 main minerals… All this makes for an enormous pharmacopoeia. “.

A brief discussion of Aconite in Ayurveda is presented first followed by a summary of Bezoars.

Vatsanabha

Vatsanabha is a useful example for drawing a contrast between the traditional Indic and western understanding of nature’s diversity.

Indic vs Western View of Vatsanabha

The names for Vatsanabha include both Visha and Amrita. Vatsanabha can be deadly poisonous but is also an invaluable herb for healing certain sickness. Rajiv Malhotra’s ‘Being Different’ [4] comments on this key principle of Ayurveda in a book section that explains the reasons behind an inherent Indic comfort with chaos:

“… The same kind of contextual sensitivity is shown in preparations of herbal medicine, as well as in medical diagnosis and prescription. Here, health is defined as the balance of opposites and involves moderating the extremes.

… Certain poisons are even used as cures in Ayurveda because toxins, too, depending on the context, have therapeutic properties. The invention of vaccination by Indians was based on the principle of using the opponent constructively to strengthen the whole system. Different plants and foods contain distinct juices (rasas) which may be harmful if taken pure, but mixing and cooking can make them useful…“.

Another ancient example of a ‘poisonous plant’ that has been used in preparing Ayurvedic medicines is धतूरा (Datura). The traditional skill and knowledge required to safely use plants like Datura in formulating medicines is just as relevant and important today:

.@SastraUniv prelim lab simulation finds anti-COVID property in toxic traditional plant to be diluted proportionately & used with another traditional material. Need access to Govt labs to validate @moayush @IndiaDST @CMOTamilNadu @Vijayabaskarofl @DrRPNishank @CSIR_IND @DBTIndia pic.twitter.com/hEgKPdBLeq

— S.Vaidhyasubramaniam (@SVaidhyasubrama) April 9, 2020

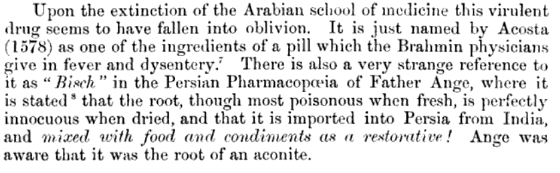

On the other hand, anxiety and confusion gripped the 19th century colonial botanists who sought a mechanistic classification rule to distinguish between ‘poisonous/harmful’ vs ‘non-poisonous/harmless’ varieties of Indian aconite. One can find Colonial-era books categorizing Visha, Ativisha, and Nirvishi simplistically as poisonous, most-poisonous (summum venenum [24]), and non-poisonous varieties of aconite, respectively. In this process, the wonderful Nirvishi (Delphinium denudatum) was erroneously classified as a ‘non-poisonous’ aconite variety. Inevitably, this rigid and fragmented western understanding resulted in Amritam being reported as a synonym of Visha [24]. Researchers were taken aback by the fact that a notorious poison (aconite comes from the Greek akonitos, attesting to its use in poisoned arrows/spear tips) was being used by Hindus as powerful restorative medicine [25]:

Kumkum Bhagya: To complete the tale of serial misfortune, the Vatsanabha antidote Jadwar (Nirvishi, Delphinium denudatum) eventually became Zedoary in English [26] which refers to an entirely different Ayurvedic root Krachura, i.e., the white turmeric variety (Curcuma zedoaria from the Sanskrit Kunkumam). This is another herb known in Ayurveda and Nirvisha is one of the 100+ Indic names attributed to this plant [19].

From plants to humans: The British Raj was applying 'race science' and classifying complex and diverse Indic Jati-Varna into the linear European category of castes [5], which can be termed the 'summum venenum' of their actions.

Aconite Toxicology in the Ayurveda

Among the eight clinical branches of Ayurveda [3], the Vishagaravairodhika prashamana deals extensively with antidotes for a variety of toxins (toxicology). This is also known as Agada Tantra. Charaka Samhita consists of eight sections of which the Chikitsasthana devotes the chapter on Vishachikitsa to a discussion of the various aspects of treating and managing cases of poisoning [27]:

“Action of poison depends upon properties of poison. If poison or venom possesses all ten properties which is described in Charaka Samhita that poison or venom becomes fatal to Human being. Hence for treating these poisoning, formulations must be potent with faster and specific actions. Vishaghna yogas are the formulations which counteract the deleterious effects of Visha (poison)…“.

Vishagna Yogas (Agadas) have also been noted in other sections of the Charaka Samhita including the kalpasthana and sutrasthana [1]. The properties of Aconite and many other herbs were analyzed, the extraction and preparation of healing medicines recorded, and the knowledge passed on over hundreds of generations. We briefly point out the three plants that are of interest to this discussion:

- Nirvishi (Delphinium denudatum [19]). Recognized as Vishadoshagni. Antidote for poisoning due to Vatsanabha, snake bites, digitalis. It has several other useful healing properties [21].

- Ativisha (Aconitum heterophyllum). Recognized as Vishavinashini in the Dhanvantari Nighantu [13]. It finds mention in the Charaka Samhita. This herb has several medicinal properties. See [20] for details.

- Vatsanabha (Aconitum ferox). This Indian aconite variety has also been identified in [31] as ‘Yat parshve na taro vriddhi’, which does not allow other plants to grow near it. It is mentioned in the ancient Sushruta Samhita [29]. It was probably known since times immemorial and mentioned in the Atharvana Veda [31] whose content includes bhaiṣajyāni for curing diseases [28]. The interested reader is referred to the ICP series on Indic medicine [3] for a broader discussion of Ayurveda and Bhaisajya.

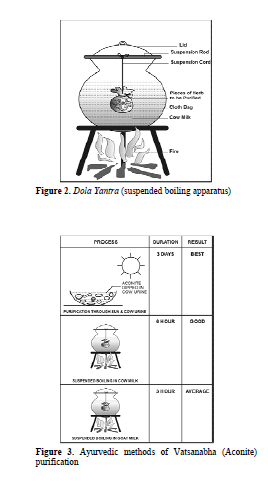

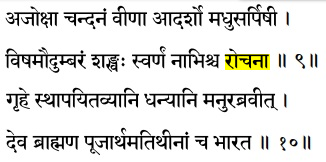

There are multiple Ayurvedic formulations that use Aconite. Ancient Ayurvedic texts recognized its toxicity and emphasized caution in the Aconite purification and treatment process prior to internal use [31].

Gorochana

That Vishaharakas (antidotes) in nature can be obtained from three sources: the earth, plants, and inside certain animals was known in India since the most ancient of times. The Deerghanjiviteeya chapter of the Sutra Sthana section of Charaka Samhita [1] classifies drugs into three types based on their origin. It lists the various substances of animal origin including honey, milk, bile, .. horns, nails, hoof, .., and finally, hardened/congealed bile (rochana).

मधूनि गोरसाः पित्तं वसा मज्जाऽसृगामिषम्||६८||

विण्मूत्रचर्मरेतोऽस्थिस्नायुशृङ्गनखाः खुराः|

जङ्गमेभ्यः प्रयुज्यन्ते केशा लोमानि रोचनाः||६९||

This last substance, rochana, refers to the bezoar. Gorochana, also referred to as Gopitta in the Indian texts is obtained from the gall bladder of the cow. Bezoars from other animals were also known but given the importance of Gau Mata in Indic civilization, the emphasis here is on Gorochana. The Visha Chikitsa chapter of the Charaka Samhita lists multiple antidote formulations containing Gorochana including the very powerful Mritasanjivana agada and mahagandhahasti [1].

The Dhanvantari Nighantu [13] is recognized as an important Ayurvedic text written prior to the 13th century CE. It mentions an ancient list of anti-toxins and antidotes along with their properties and actions. It recognizes Gorochana as a vishahara, a destroyer of poison. A survey of Ayurvedic texts containing Jantava dravyas, i.e. formulations of animal origin including Gorochana, Kasthuri, and Mrigsringi [12], cites several sources that discuss Gorochana and its multiple properties and benefits:

"Gorochana is also called as pingala, pinga, medhya, gouri, gomati, mangalya, vandaniya, ruchira, agrya, pavaki and ruche,

It is pachana, sheetaveerya, soubhagyadayi. It alleviates visha, netravikara, bhutabdha, and grihabadha." - Dhanvantari Nighantu.

Among the eight auspicious substances mentioned in The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols [9]: we find that ‘precious medicine’ refers to Gorochana. The author remarks: “The precious medicine is derived from the intestinal-stones or gallstones that are found in certain animals, particularly elephants, bears, and cattle. The Sanskrit term gorochana refers specifically to the stones or ‘bezoars’ found in cattle…

The story of the transcendental provenance of Bezoars is narrated by the author and is interesting for the links established between various entities of the cosmos:

“A Vedic legend relates how the god Indra once cast the five precious minerals: gold, silver, coral, pearl, and sapphire or turquoise, into the great ocean. These precious substances were eventually consumed by elephants, bears, … pigeons, which then formed bezoars within their bodies. …

Their medicinal properties are reputed to counteract poisoning, promote clear thoughts, and alleviate fevers and contagious diseases. The superior, mediocre, and inferior forms of

these stones are reputed to respectively cure seven, five, or three patients who have been

poisoned.”

A slightly different set of five precious substances that grace Mahavishnu’s Vaijayantimala correspond to the Panchamahabhutas, the five elements of nature that are discussed in the Charaka Samhita.

The use of Bezoar-stone like Vishakallu has been known for long within the native healing customs of Southern India [22]: “a kind of medicated stone, “Vishakallu” (poison stone), is used by the indigenous group “Kani” in Kerala, India, to treat snakebite …”. Given this widespread knowledge of antidotes in India unlike the west, it is difficult to find many Indian stories of fake Bezoars. Gorochana was considered sacred in India and available for the benefit of all, unlike the Bezoar in the west that was marketed exclusively to the rich and powerful.

Indic knowledge traditions are reduced to "ethnobotany", "ethnomedicine", "ethnomathematics", etc., while the western medical, agricultural, and botanical sciences that emerged by digesting Indic traditions are privileged as "universal/mainstream".

Smriti, Purana, & Itihasa

- The ancient Vishnusmriti [14], Chapter 23 and Verse 58, mentions Gorochana as one among six beneficial and propitious products that come from the cow.

- गोमूत्रगोमयं सर्पि क्षीरं दधि च रोचना ।

- षदंगमेतत् परमं मांगल्यं सर्वदा गवाम् ॥

- The 12th century sacred Tamil text Periyapuranam [30] was recently featured in our daughter portal and has stanzas mentioning the Seva performed by the great Hindu saint Nandanar who was a humble leather worker by profession. Nandanar, who lived prior to the 8th century CE, extracted the sacred Gorochana from cows and offered it to the nearby temples for Pooja (stanza 14). Evidently, knowledge of Gorochana existed in different communities since ancient times.

- … சேர்வுற்ற தந்திரியும் தேவர்

- பிரான் அர்ச்சனை கட்கு

- ஆர்வத்தினுடன் கோரோசனையும் இவை

- அளித்து உள்ளார்.

- Vidura’s words (Vidura Neeti) in the Udyoga Parva of the Mahabharata [15] mentions Gorochana and other substances that are considered auspicious. Unsurprisingly, many of the items mentioned here are also present in the Tibetan list:

- Baij Nath Lala [10] cites the Drona Parva to list the activities that are to be ideally followed by a Hindu King (Yudhishthira as exemplar), stating that he “touched various articles calculated to bring good fortune, — clarified butter, honey, gorochana -and looked at floral garlands, waterpots, auspicious and well-decked maidens, and then entered his audience chamber.“

- In the Anushasana Parva of the Mahabharata [16], we find a Gorochana-Purusa connection: “That man who worships every day the Aswattha (Ficus religiosa) and the substance called Gorochana and the cow, is regarded as worshipping the whole universe ..“

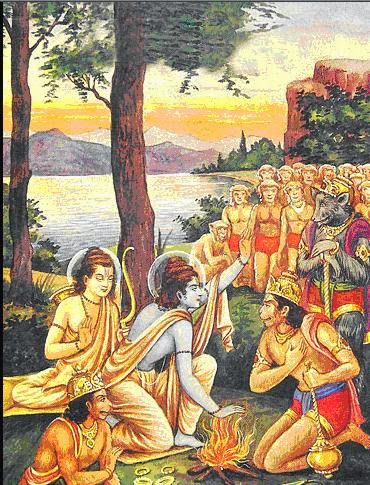

- Finally, the most ancient Valmiki Ramayana Adikavya [17, 18] mentions Gorochana in the Kishkinda Kandam when Sugriva is welcomed back to Kishkinda by his subjects with a variety of gifts and offerings:

- दधि चर्म च वैयाघ्रम् परार्ध्ये च अपि उपानहौ ||

- समालंभनम् आदाय गोरोचनम् मनः शिलाम् |

References:

- Charak Samhita Live Edition. The Definitive Online Edition of Ayurveda‘s Core Treatise on Healthcare.

- Science and Society: An Indian Perspective. Ancient Indian Medicine: Towards an Unbiased Perspective. Centre for Policy Studies, India. 2011.

- Nripathi. Classical Indic Medicine: Ayurveda. 2018.

- Rajiv Malhotra. Being Different: An Indian Challenge to Western Universalism. Harper Collins. 2011.

- Rajiv Malhotra. Breaking India: Western Interventions in Dravidian and Dalit Faultlines. Amaryllis. 2011.

- Abu Rayhan Muhammad Ibn Ahmad Al-Biruni. The Book Most Comprehensive in Knowledge on Precious Stones: Al-Beruni’s book on mineralogy. Edited by Hakim Mohammed Said. Pakistan Hijra Council. 1989.

- C.P. Khare. Indian Herbal Remedies: Rational Western Therapy, Ayurvedic and Other Traditional Usage, Botany. 2004.

- William Dymock, CJH Warden, D Hooper. Pharmacographia Indica, A History of the Principal Drugs of Vegetable Origin Met with in British India. Vol 1. 1890.

- Robert Beer. The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Shambhala. 2003.

- Baij Nath Lala. Hinduism Ancient and Modern: As Taught in Original Sources and Illustrated in Practical Life. 1905.

- Abhinash Chandra Kaviratna. Charaka Samhita: The Greatest Scientific Work of Ancient Indian Wisdom. Translated into English. Calcutta. 1890.

- Umakant N.R. Introduction of Jantava Dravyas-Gorochana, Kasturi, Mrigasringi – A Literary Survey. International Journal of Applied Ayurved Research. Vol. 3. 2018.

- Reshmi Pushpan, Smitha Jain, Anita M. G., and K. Nishteswar. A Review of Vishahara Dravyas (Alexiterics) of Dhanvantari Nighantu. International Journal of Research in Ayurveda and Pharmacy. Vol. 8. 2017.

- विष्णुस्मृति – The Institutes of Vishnu- Together with Extracts from the Sanskrit Commentary of Nanda Pandita called Vaijayanti. 1881.

- Vidura Neeti: Sanskrit Text with English Translation. http://www.sanskritebooks.org.

- The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa. Book 13: Anushasana Parva. Translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli.

- Valmiki Ramayan, Book Four. Chapter 26. ValmikiRamayan.net.

- Valmiki Ramayana: Kishkindha Kandam. Translation by Girish Chandra Chackravarti, 1891.

- Umberto Quattrocchi. Medicinal and Poisonous Plants: Common Names, Scientific Names, Eponyms, Synonyms, and Etymology. CRC Press. 2012.

- M.D. Ukani, N.K Mehta, and D.D Nanavati. Aconitum Heterophyllum (Ativisha) in Ayurveda. Ancient Science of Life. Vol. 16. 1996.

- Jadwar- Delphinium Denudatum Uses, Research, Side effects.

- P. Durairaj, M. Kamaraj, S. Senthil Kumar. Ethnobotanical survey of folk plants for the treatment of Snakebites in Tiruchrapalli district of Tamil Nadu, South India. International Journal of Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences. Vol 3. 2012.

- Lt.Col. Madden. Elucidation of some Plants mentioned in Dr. Francis Hamilton’s Account of the Kingdom of Nepal. Transactions of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh. 1858.

- John Forbes Royle. Illustrations of the Botany and Other Branches of the Natural History of the Himalayan Mountains (etc.) 1839.

-

Friedrich August Flückiger, Daniel Hanburgy. Pharmacographia: A History of the Principal Drugs of Vegetable Origin, Met with in Great Britain and British India. 1879

-

The Pharmaceutical Journal. The Official Organ of the Pharmaceutical Society. Vol 75. 1905.

- PVU Venkatrao, and RP Prahlad. Vishaghna Yogas in Charak Samhita. International Ayurvedic Medical Journal. Vol 6. 2018.

- Niranjan Jena. Ecological Awareness Reflected in the Atharvaveda. Bharatiya Kala Prakashan. 2002.

- Kaviraj KL Bhishagratna (Editor). An English Translation of the Sushruta Samhita. Calcutta. 1911.

- Sekkizhar. Thirunalaippovar Nayanar Puranam of Periyapuranam. shaivam.org.

- Sanjeev Rastogi. A review of Aconite Vatsanabha usage in Ayurvedic formulations: traditional views and their inferences. 2011.