The Ancient Chronicles of Sri Lanka are the Deepavamsa and Mahavamsa respectively. Though blended with mythical origins, they are nevertheless, the most complete history from antiquity on the Sinhala people. While they are a distinct ethnic-nation, the Sinhalese have long acknowledged their connection to Indic Civilization, and are seen as fellow dharmics by many/most Hindus.

Appreciating difference within a common cultural matrix is what has allowed Dharmic culture to flourish for millennia. Top-down, narrow-minded and rigid impositions (along with cookie-cutter, 1-size-fits-all solutions) are what has typically led to antagonism and misunderstanding between peoples of a common origin. This is all-the-more high stakes when there are people of differing origin, but common cultural cause within a territorial nation, or civilizational state.

The beautiful Island of Ceylon deserves recognition for its own civilizational contributions and cultural history. What better way to begin than with its ancient-most chronicle: The Deepavamsa.

Author

Composition

The voyage of Prince Vijaya is the stuff of legend, and yet, shows precisely how the ethnic warp-and-weft of this once war-torn land, weaves back into the Indian weave.

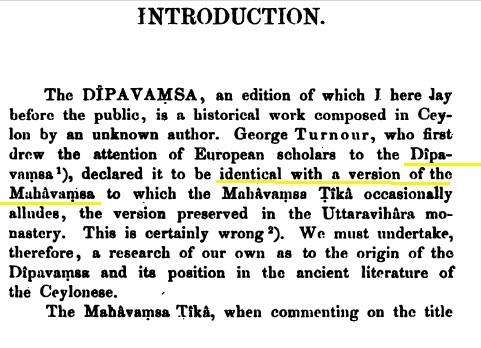

The Dheepavamsa and Mahavamsa are described as two versions of the same substance. While some argue that the texts are different, it is quite clear that they may as well be different recensions of the same text. They effectively commence the same way, cover the same topics, and serve the same purpose.

Of the two, the Dheepavamsa is deemed the elder, and is dated to approximately 302 CE. It is seen by some as a more incomplete redaction of an earlier text. Available manuscripts are found to have gaps in them, making scholars more reliant on the later Mahavamsa.

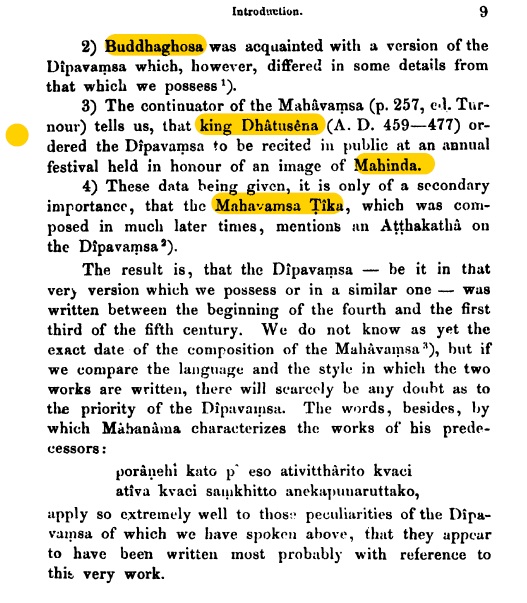

Interestingly, the Dheepvamsa was ordered to be recited in the Royal Court of Sri Lanka. The great Buddhaghosa was also acquainted with it, and is credited with the sinhalese Samanta-paasaadika. There is also a Mahavamsa teeka on it. Both the Dheepavamsa and Mahavamsa were works in Pali, but were found in foreign alphabets as far as Burma (Myanmar) and Tibet.

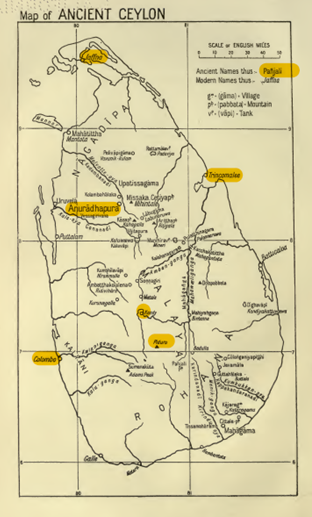

Both the Dheepavamsa and Mahavamsa go into tremendous description of geographical sites. Not only is the island of Sri Lanka itself discussed, but the founding of key cities such as Thamraparni and Anuraadhapura are also mentioned.

Nevertheless, Sinhala and its kings have their own identity, which, along with the Tamil, should be respected in due measure. However, the links between Sinhala and Southern Nepal, via the Buddha, should not minimised. The Dheepavamsa is intrinsically a Buddhist work, and the centrality of Siddhartha Gautama is apparent throughout the text.

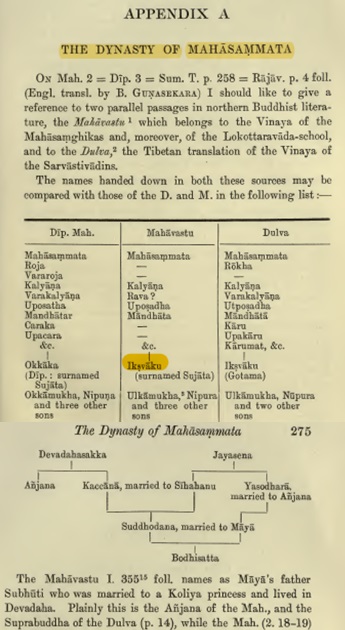

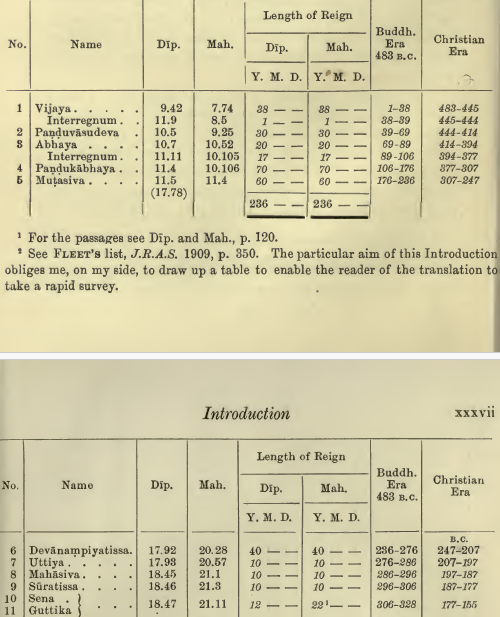

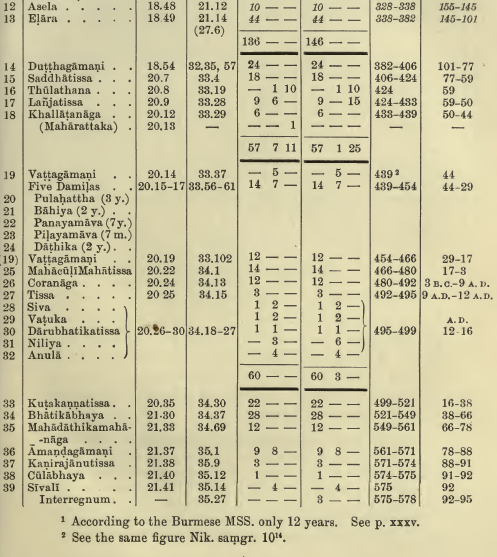

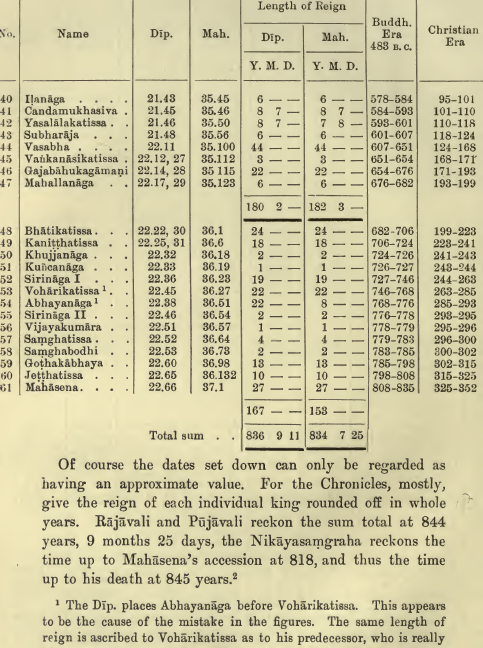

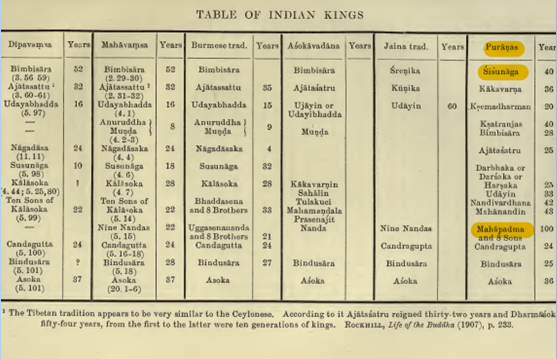

The various lineages of Emperors of Magadha are discussed along with contemporaneous Sinhalese Kings. Nearly 600 Hundred years worth of monarchs are mentioned. It is an exhaustive litany of the potentates of this island, during its earliest ages.

Although it is quite clearly a Buddhist text, tying the Thathagatha with the very importance of the island, it places Sinhala within the wider Civilization of Bhaarathavarsha, which it frequently describes via the bauddha malaprop “Jambudipa”. Jambudhveepa, of course, refers to the entire Continent of Eurasia, with Bhaarathavarsha/Bhaarathakhanda referring to the Indic division of the Island of the Rose-apple vine.

Despite the incongruent minutiae, it is evident that the Dheepavamsa-Mahavamsa corpus was of singular importance in the history and tradition of Sinhala dhveepa. It is an island nation of tremendous antiquity, with frequent interactions not only with the Tamils of Southern India, but with the peoples of Bihar and Bengal in Northern and Eastern India.

The connections and connectivity between these regions was made possible not only via the mature navigation capabilities of these peoples, but also the long-standing shipping lanes between various port-cities across the subcontinent. These, of course, are best understood by closely reading selections of the composition itself.

Selections

Descriptions of the Island of Sinhala in the Dheepavamsa are vivid and illustrative in its length and breadth. Geographical features redound in copious detail. Its natural wealth and beauty are caught in captivating imagery. The text notably uses the classical indic measure of yojana in this Sri Lankan text.

§

The first monarch of the Sinhalese traces his origins to Bengal (Vanga desa). However, he and his coterie were soon exiled by the King for their irresponsible conduct.

§

Devanampiya Tissa’s conversion to Buddhism via Devanampiya Maurya’s son Mahinda. Devanampiya Tissa is described as Emperor Ashoka’s friend and ally, following the former’s conversion to the Bauddha Dharma.

§

Sri Lanka’s connections with India and Buddhism go beyond the conversion. The Sinhalese royals themselves married into the Sakkiya/Sakka (Saakya) clan of Southern Nepal/Northern Bihar. The progenitor of this line was interestingly named Pandu.

Conclusion

All and all, the connections between the two societies are apparent. A nation and civilization are two different but related politico-cultural formations. Indosphere or otherwise, Sanskrit and Sanskrit-descended languages such as Prakrit/Paali connected the peoples of Southern and South-east Asia in a way that is difficult for other civilizations to match. It is not only about ethnicity or culture, but the cultural mores and spiritual morays that imbue the peoples at the heart of the Indian Ocean.

With Sathya as the foundational value, ethnic identities can be valued but transcended in the aim of a shared humanity. Vasudaiva Kutumbakam, via Dharma of course.

References:

- Oldenberg, Hermann. The Dipavamsa. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services.1992

- Geiger, Wilhelm. The Mahavamsa. Oxford. 1912