After a long gap, we return to matters literary. Classical Indic Literature is often classed as the epitome of inspirational, heroic, and virtuous composition. Poetry, poesy, and poetics itself were not only systemised, but also subjected to the rigours of Sanskrit and Sanskritic composition.

“The mahakavya (epic form) of literature with its themes based on puranic or historical episode and containing all the essential features of poetic embellishments was a product of this age. Benevolent monarchs, who themselves were endowed with literary talent, encouraged such poetic writings.” [1,9]

However, the influence of Indic Epic literature was not limited to India itself. It cast wide shadows across caste and country lines in a veritable Indosphere.

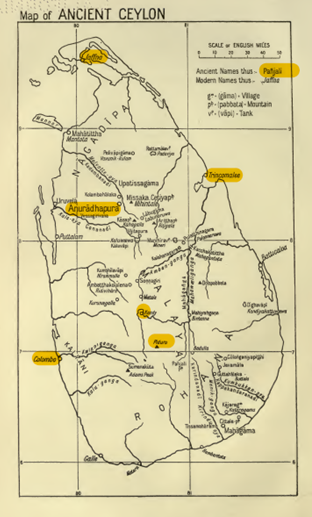

One of those key countries in greater Bhaarathavarsha was Sinhala Dhveepa—known to us today as modern Sri Lanka. Indeed, it produced a Kumaradasa who once received and hosted our own Kalidasa. But to understand the impact of and the connection between the two, a brief history lesson is in order.

Introduction

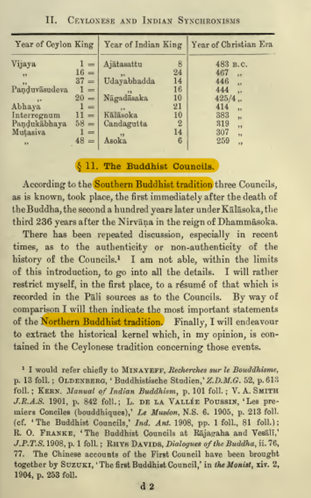

Sri Lanka and the Sinhalese language and culture remain both independent and distinct from India, and yet, intrinsically united with it. This modern, mostly Buddhist country hosts both the Theravada and Hindu cultures, along with other world religions. However, relations between the parent civilization and the sovereign country were not always acrimonious. From Devanampiya and Devanampiya Tissa to Kalidasa and Kumaradasa, there was a massive cultural connect between the two dharmic lands. The origins of this unveil just how deep-rooted the relationship is.

Sinhala Dhveepa

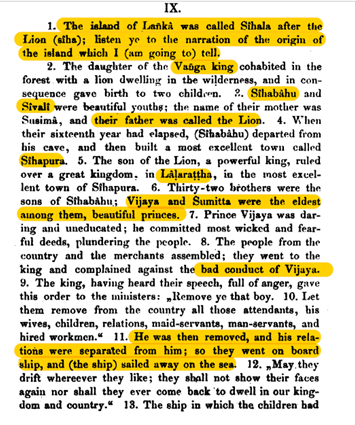

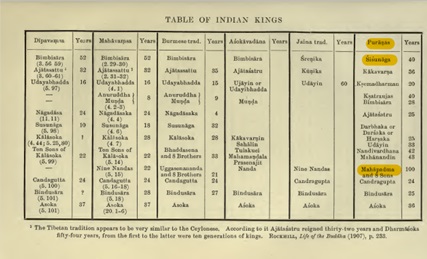

There are 2 great epics in the history of Sinhala dhveepa. These are the Deepavamsa and the Mahavamsa . The voyage of Prince Vijaya is the stuff of legend, and yet, shows precisely how the ethnic warp-and-weft of this once war-torn land, weaves back into the Indian weave.

The first monarch of the Sinhalese traces his origins to Bengal (Vanga desa). However, he and his coterie were soon exiled by the King for their irresponsible conduct.

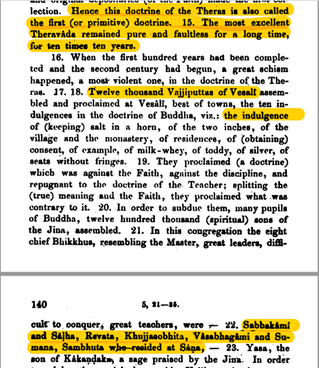

Interestingly, the Deepavamsa refers to Mahayana to as ‘heretical’ and ‘sinful’ in the view of strict Theravadins. No doubt, the criminal Kapalikas infiltrated here too, having already caused great damage to the Vaidika dharma.

Background

“The classical age of Sanskrit literature generally known as the Golden Era, which is identified with the post-Gupta period of Indian history, brought out some of the best literary creations.” [1, 1]

The cultural impact of this period can be found throughout Indic Civilization. From Kashmir to Kerala, this was no exception (even in that extension known as Sri Lanka).

“A complete manuscript of the original Sanskrit poem transcri-bed in Malayalam script was, providentially procured by the Government Oriental Manuscripts Library, Madras, in 1920…Identification of quotations from Janakiharana in a metrical work entitled Janasrayi Chandoviciti provided the clue to fix an upper limit to the date of Kuamradasa. King Madhava Varman of the Vishnu Kundin dynasty of Andhra Pradesh, also known as Janasraya, author of the work on metres, belongs to the last quarter of the 6th century.” [1, 10]

One can see here, not only the centrality of Sanskrit in Classical Indic Culture, whether in Bhaarathavarsha or Sinhala dhveepa, but also the cultural impact of the Imperial Pallavas. Dhraavida Desa (modern Tamil Nadu & Kerala)and Sinhala dheevpa frequently intervened in each other’s affairs; however, the relationship between Dharmic Tamils and Sinhalese was not always adversarial. In matters cultural and civilizational, the two would often be reminded of the greater literary kinship.

Kumaradasa himself provides information on himself. In this particular manuscript, the colophon contains the requisite biographical evidence to sketch out his background.

“From the colophonic verses of the Madras man-uscript of Janakiharana, we learn that the poet’s father was Manita, a military officer in-charge of the rear guard of King Kumaramani of Ceylon; that he lost his life in the battlefield; that the poet had two powerful uncles, Megha and Agrabodhi, who brought him up from infancy; that he was a sickly child and that he wrote the poem under the patronage of his uncles.” [1, 10]

Tragedy often inspires the most eloquent of works. Kumaradasa’s life proved to be no exception. With repeat exiles to Sri Vijaya and Bhaarathavarsha proper, poesy provided plenty of passtime to this peripathetic prince.

“In 1967, two Sinhalese scholars, Paranavitana and Godakum-bara brought to the notice of scholars a 9th century inscription on a pillar in Madilla in Sri Lanka, According to it, in the troubled political situation that was prevalent in Sinhala, a Yuvaraja by name Mana was killed and his infant son was taken away to a place of safety on the mountains. This son was named Kumara Dhatusena was was taken to Srivijaya, beyond the seas for security reasons. The exiled prince studied Sanskrit and reached Kanchipuram along with his cousin Manavarman and sought the help of the Pallava king…He studied under Dandin and began composing his poem Janakiharana, at Kanchipuram, with the help of the benevolent King Narasim-havarman.” [1, 10]

“Manavarman captured the Sinhalese throne, continued to patronise the poet and made him a Yuvaraja. When Agra-bodhi V, son of Manavarman, came to the throne, the poet had to flee Sri Lanka again and take refuge in Srivijaya. The king of Srivijaya being a Buddhist, asked the poet to write a poem on a Buddhist theme and accordingly he wrote Srighananda on the lines of Asvaghosa’s Soundarananda. Kumaradasa eventually returned to Sri Lanka and met his end there.” [1, 11]

His princely peregrinations now in the past, kingly Kumaradasa could now take up his royal duties in tandem with his poetic predilections.

Kumaradasa & Kalidasa

krittika 🔥

alba by kumāradāsa pic.twitter.com/YDdoSQFzn5— śivamayī 𓃠 (@shreemastrology) July 11, 2022

The twain are connected not only by poesy, but by history, and yet Kalidasa’s sojourn in Kumaradasa’s kingdom is said to be marked by tragedy.

Obligated to visit Kumaradasa after so many months, Kalidasa eventually took his leave and crossed the Palk Strait to Sri Lanka. One night he crossed paths with a courtesan named Kaamini. Though she did not know who he was, she was intrigued by this old man from India.

“O stranger to this land, you come from India where people are honest, trustworthy and observe the dharma. You inspire confidence in me and I will tell you why I am awake at this hour.” [4, 16]

This young beauty said she was the sweetheart of Kumaradasa. Though her love for him was requited, the prince had laid down a condition for marriage: He had composed a half a verse that she was to complete. However, the task was beyond her, and she asked this most skilled of poets to help her.

Elated, Kaamini thanked Kalidasa and led him to a room to rest. However, fear soon overcame the courtesan, and she wondered what would happen if Kumaradasa discovered she did not complete the couplet. Worried that he wouldn’t marry her if he found out the truth, she secreted herself back into the old man’s room and stabbed him in the heart.

The most celebrated of poets cried out in agony, “Kumargupta, Goodbye. Kalidas is unlucky; he could not see you“. [4, 17] Then he died.

Horrified at what she had heard, Kaamini checked his baggage to see if it was indeed the Raja Kavi, and she soon found a copy of Meghaduta, along with a freshly composed kavya. She cursed herself and then killed herself with the same knife. The next day Kumaradasa came to the villa only to stumble upon the horrific scene. He read the newly composed couplet and the freshly composed poem, and realised what had happened. It is said that at Kaamini’s and Kalidasa’s funeral, the Prince was so overcome by grief that he jumped onto Kalidasa’s pyre with the couplet in his hand.

So passed the Sanskrit similist in Ceylon. The story may stretch credulity, but it nonetheless accounts for the poet’s vast knowledge of the length and breadth of the Indian Subcontinent.

Whether united by fire or by literature, Kumaradasa’s work shows the influence of Kalidasa.

“The Suktimuktavali of Jalhana, an anthology of quotes from other poets, contains a number of eulogies by poet Rajasekhara on earlier poets. One of these, as already mentioned, contains a re[f]erence to Kumaradasa’s Janakiharana and Kalidasa’s Raghuvamsa.” [1, 18]

“The last canto of Janakiharana is based on the 13th canto of the Raghuvamsa. Both deal with the same part of the story, Rama’s journey to Ayodhya by the aerial chariot. The very first verse of the 13th canto of Raghuvamsa is echoed in the third verse of the 20th canto in Janakiharana. The description of the oceans, forests, hermitages, mountains and rivers are similar to those in the Raghuvamsa; the only difference being that he adds a description of the Himalayas not found in the Raghuvamsa but again inspired by the description of Himavan in the opening canto of Kalidasa’s Kumarasambhava.” [1, 20]

Achievements

- Prince (sometimes mentioned as King) of Sinhala dhveepa (island of Sri Lanka)

- Credited with the Srighananda & most notably Janakiharanam Mahakavya poems

- Janakiharanam: is a work in 20 cantos [1, 1]

- Employs as many as 23 metres, with vamsastha as the most common one

The Janakiharanam remains Kumaradasa’s singularly spectacular achievement. Though he is said to have authored other compositions, including a Bauddha one at the request of Sri Vijaya’s Buddhist king, he is best known for this.

“He has exhibited his skill in handling the most popular metres like the vamsastha as well as the rare ones like the nardataka. He handles these metres with ease. Following the poetic conven-tion, he generally employs a single metre throughout a canto, with large ones to mark the conclusion of each canto.” [1, 47]

Janakiharanam

Kumaradasa limits the scope of this epic poem to the subjected-matter of Raavana’s abduction of Seetha Devi and Sri Raama’s subsequent battle and rescue of her. There are vivid descriptions of the goings-on of royal palaces as well as seasonal descriptions worthy of the Rtusamhara.

Kumaradasa is open in his respect for Valmiki , and there are passages of his work that causes one to reminisce of the Aadhikavi himself:

Tvayaa jaraavesajadikrtasya vane vinaathasya gurudvayasya

Vicakshushoyam vrata jeernamurteh bhagnah kimaalam-banadanda ekah

Why did you break the only supporting staff of the helpless blind parents, emaciated by vows and imma-culate by old age.

(Janakiharana, I.75)

Gatistvamagateenaam ca caksustvam heenacakshushaam

samaasaktaastvayi praanah

You are the hope for the otherwise hopeless, you are the eyes for the blind and our life breath depends upon you.

(Ramayana, Balakanda, 64.10)” [1, 15]

“Sandhyaaraagotthithaisthaamraih anteshvadhikapaandaraih

Snigdhaairabhrapatacchedaiah Baddhavrana mivaambaram.

The sky looks as if bearing a bandage on wounds in the form of dark bits of clothes in the form of clouds which are tawny due to the evening twilight and are whitish on the edges.

(Ramayana, Kiskindha Kanda, 28.5)

The foregoing lines of Kumaradasa have close similarity with the above.

Niraasasyotkasya shutati navameghasya hrdaye

rayaadudyaddhaaraa asrja iva nirbhaanti taditah

The lightning appear in the midst of the fresh clouds, like the gushing streams of blood from a broken heart.

(Janakiharana, XI.96)”

[1, 17]

Kumaradasa the Scholar

Though a poet at heart, not much is known about our literary hero other than his scholarly reach. Indeed, in many ways, a true poet was not a mere wordsmith, but combined the virtues of learned men with the artistry of bards.

“The Indian idea of the poet tended from early periods to become a combination of learning and artistic gift, i.e.vyutpatti and sakti. The greatest of the poets was also a profound scholar; but one like Kalidasa carried his learning lightly, and the instances where his erudition showed itself were few and far bet-ween.” [1, 49]

“While Kalidasa introduces such learned ideas but rarely and mostly through similies, Kumaradasa presses into service slesa (paronomasia) A survey of the instances where Kumaradasa shows his skill in enriching his work with learned concepts, proves his acquaintance with the whole field of Sanskrit learning.” [1, 49]

Most interesting, however, is the entrance of one of the shaddarsanas into the discussion. Notably, it is the dhrshti of Kapila himself that makes its entrance in the compositional world of Kumaradasa.

“Kumaradasa’s knowledge of the Sankhya philosophy is con-firmed by a verse where he describes the armies of raksasas who come to spoil the sacrifice of Visvamitra. The entire verse with the help of slesa presents one of the fundamental doctrines of the Sankhya school, namely the three gunas:

Pisaacaraksastatibhirnirantaram

krtaandhakaaram rathacakrarenubhih

Asaankhyagrhyaa api tatua sainikaah

Jagajjagussatvarajastamomayam

The verse literally means:

“The innumerable hordes of pisacas and raksasas, creating darkness by the dust raised by the wheels of their chariots, though they were not Sankyas, proclimed the world as con-stituted of sattva, rajas and tamas.” [1, 51]

“Throughout his poem, Kumaradasa exhibits his close acquain-tance with the Puranas and the Itihasas. Many stories and anecdotes contained in Hindu mythological literature are refer-red to by the poet on various occasions…in Canto II he refers to the omiscience and omnipotence of Visnu” [1, 56]

“The poet shows familiarity with Buddhist literature as well. In the contexts of sending the princes for the assistance of Visvamitra, Kumaradasa emphasises the importance of paropakara or service to others which is in line with the Buddhist teachings.” [1, 52]

Nevertheless, one sees the breadth of the poet-king’s comprehension extend past poesy and philosophy to proper artistry as well. Specifically, once can see the interconnectedness of Classical Indic Sangeeta.

Kumaradasa also demonstrated his acquaintance with music and dance, notably in canto VIII, v.100:

“Athahrdayangamadhvanita vamsamrdanga krtaanugamai-ranugatavallakeemrdutarakvanitairlalanaah

Tamusasi bhinnasadjavisayeekrtamandaravai

Ssayitamabodhayan vivdhamangalageetipadhaih

The orchestra in attendance comprises flute (vams[i]) drum (mrdanga) and lute (vallaki), to the accompaniment of which ladies sing auspicious songs (mangala-giti-padas).” [1, 61]

Legacy

Kumaradasa is regarded, not unduly, for his mastery of slesa (paronomasia) and vyuthpathhi (mastery in vocabulary & grammar)

“Janakiharana by Kumaradasa is a product of that era. Belonging to Sinhala (Ceylon), Kumaradasa came under the compelling influence of Kalidasa. Traditional legends abound indicating the contemporaneity of these two poets. ” [1, 1]

“The ideal of mahakavya as the medium of presenting a noble heroic character for the edification of the reader, engendered the bringing into the writing the essential elements of Indian culture as enunciated in the various branches of mental and moral disciplines. Poetry thus gradually assumed in a pronounced manner, an educative role; it was thought of as a legitimate medium for expounding scholarly matters.” [1, 49]

The Janakiharanam is remembered as a luminescent case of this. Descriptions are vibrant and yet tasteful (a concept many modern pedants have yet to grasp…). It is teeming with pathos and remains Kumaradasa’s preeminent legacy in the subcontinent.

Perhaps it is best to remember the Sinhalese Prince and Indic Personality Kumaradasa as the poet Rajasekhara did, by underscoring his poetic daring in naming the elite literary company beside which he could sit.

“There is a reference in Janakiharana (I-17) to the ruler of Kataha (Kedah in Malaya) and the reference to the commercial importance of Kanchi (I-18) or Kanchipuram. Rajasekhara makes a specific reference to both Kalidasa and Kumaradasa in the following verse:

Jaanajeeharanam kartum Raghuvamse purah sthite

Kavih Kumaaradaaso vaa Raavana vaa yadi kshamah

When Raghuvamsa (the royal family of Raghus) is already there, only Ravana and poet Kumaradasa could dare to do Janaki harana (the abduction of Sita or the poem of that name).” [1,11]

References:

- Swaminathan, C.R. Kumaradasa. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. 1990

- Oldenberg, Hermann. The Dipavamsa. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services.1992

- Geiger, Wilhelm. The Mahavamsa. Oxford. 1912

- Bhatt, H.D. Shailesh. The Story of Kalidas. Publications Division, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting. Govt. of India. 2003