From Antifragility to Integrality

Note: Emphases within quotes are added by this author.

Section-1: The Roots of Fragility

“Logically, the exact opposite of a “fragile” parcel would be a package [whose] contents would not just be unbreakable, but would benefit from shocks and a wide array of trauma…We gave the appellation “antifragile” to such a package; a neologism was necessary as there is no simple, noncompound word in the Oxford English Dictionary that expresses the point of reverse fragility. For the idea of antifragility is not part of our consciousness—but, luckily, it is part of our ancestral behavior, our biological apparatus, and a ubiquitous property of every system that has survived.” – Taleb, Nassim Nicholas [5].

Reading the above extract, it is tempting to argue the following:

Dharma civilization has continuously survived, flourishes and grows to this day because it is antifragile whereas others were fragile and self-destructed due to internal contradictions or perished due to external onslaught. This is too simplistic an explanation. Dharma transcends antifragility and thrives by embracing its deeper vision of purna or ‘integral unity’ [8], i.e., integrality.

The opposite of fragility is not robustness, and the neologism of antifragility also falls short. The opposite of fragility is integrality.

The western worldview of a synthesized universe has enabled the west to materially advance through mass mechanization and instrumentation in the last few centuries. An implicit belief is that the world around us is ultimately made of separable components, with a robust ‘God’ exiled to an irreconcilably different domain. The best that such a system can achieve is limited to local antifragility (gaining from small shocks) [11] since any synthetic union is intrinsically fragile and falls apart when subjected to sufficiently high stress.

Tesla wants to die-cast nearly the entire underbody as one piece versus the 400 parts of a conventional car. https://t.co/adBcq8xRE0

— Popular Science (@PopSci) September 24, 2023

Every synthesized entity is fragile and perishable. The opposite is the integral entity that is imperishable.

Integral is not the same as robust. To avoid this confusion, we must turn to dharmic teachings to understand integrality, whose deep understanding and real-world application is unique to dharma civilization.

Antifragile Jarasandha, Robust Bheema, and Integral Sri Krishna Avatara

Integrality arises from the ancient Vedic understanding that our world is ultimately not a union of independent components but a seamless unity of Consciousness. In the Mahabharata, the seemingly invincible King Jarasandha epitomizes (local) antifragility. Every time he’s taken slightly apart in battle he recombines and returns reinvigorated. In the ultimate analysis, his fragility and fault-line persists because his body was formed through a synthetic union of two halves; he lacks integrality. The robust Bheema eventually starts to tire in this dvandha yuddha (duel) with antifragility. Sri Krishna paramatma who embodies integrality, enlightens Bheema about the limits of Jarasandha’s antifragility. Bheema permanently ends Jarasandha’s tyranny by taking him apart and throwing the two halves sufficiently away from each other.

To better understand the integrality property we turn to a brilliant modern commentary of Sri U.V. Ranganathan Swamy on the Bhagavad Gita. A section of this talk focuses on two verses from Chapter-2 of the Gita [1] that tell us everything about integrality versus fragility.

Verse-17 talks of the all-pervasive atma and its indestructability.

अविनाशि तु तद्विद्धि येन सर्वमिदं ततम् |

विनाशमव्ययस्यास्य न कश्चित्कर्तुमर्हति ||

The video commentary then explains the next verse (18) that compares a deha (from diha upachaye, i.e., synthesis of components; the human body is a deha) that is intrinsically fragile, unlike the atma that is component-less and integral and therefore untouched by fragility.

अन्तवन्त इमे देहा नित्यस्योक्ता: शरीरिण: |

अनाशिनोऽप्रमेयस्य तस्माद्युध्यस्व भारत ||

The two-point summary of this discourse on the indestructibility of the atma is as follows:

- The atma is so subtle that it pervades everything and cannot be pervaded by anything else and therefore cannot be destroyed.

- This atma does not have any components (unlike a Deha), so it cannot be destroyed.

A crystal-clear meaning of ‘fragile’ (and its antithesis) is obtained automatically from these two shlokas as ‘that which is not integral’ or ‘that which is made up of components.’

Fragmented Worldview versus Integrality

The western assumption of an inherently fragmented world, which stands in stark contrast to the lessons in the Gita, is nicely captured in a philosophy blog [10] (see this post for context).

“… much of Western civilization is based on separating the parts. One date is separate from another, history separate from math which is separate from biology. It’s a world view we inherited from Newton and Descartes, so useful in many ways and disastrous in others. However, there has always been an alternative view of the universe as a single, totally interconnected system. You’ll find that in Eastern traditions, American Transcendentalism, and at least some aspects of quantum physics.”

For example, Mathematics and Philosophy are separate fields whereas their Indic counterparts, Ganita and Darshana, are integral. The hyphenated identity of the “philosopher-doer” is another synthetic construct, as opposed to the Yogi. The ‘Antifragile’ book [5] associates the monotheist God with robustness. On the other hand, Bhagavan is integral. A full discussion of the western predilection for synthetic unity can be found in Sri Rajiv Malhotra’s book ‘Being Different’ [8]. Note that the views of “Eastern traditions, American Transcendentalism, and at least some aspects of quantum physics” mentioned above are not different sources as each one traces back to the ancient Vedic principle of integrality (or integral unity): the seemingly different parts, variability, and diversity that surround us are but a dependent reality, with no independent existence of their own as they are manifestations of one ultimate reality [8].

Given the unsurpassed longevity of dharma civilization, it is apparent that sustainability is better understood in terms of fragility-integrality, rather than the fragility-antifragility guidebook for a world governed by pure, non-karmic randomness.

Decolonization as fragility reduction

Rather than think in terms of binaries, it is practically useful to use the degree of integrality as a measure of inherent fragility. The two waves of colonialism that besieged India led to unprecedented loss of life and loot, but it is only now we see its long term civilizational impact in the form of mental colonization. This is where society is eager to embrace the gains of synthesized unity offered by modernity that consists of superficially strong but intrinsically fragile connections (e.g., mutually beneficial deals) between constituents. Such a system grows in complexity and latent fragility and eventually collapses [13, 17]. Avoiding this fate requires genuine decolonization (very different from the materialist theory of decoloniality proposed by Marxist schools of thought) where external socio-political rejuvenation emerges from a corresponding inner transformation within us (in short, a Yajna). Without such an integral transformation, a colonized people will remain fragile and end up replacing the colonizer’s fallacies with home-brewed versions and turn into re-de-re-colonized trishankus.

The Ganita of decolonizing is simply this: to continually become less fragile and more integral at every level.

This inner-decolonization cannot be achieved by only moving away from something negative but by moving toward Satya (e.g., through vrata, Ritamic decision policy, part 4) and replacing every entrenched fragilizing dependency. Our most significant fragility is our past karma that is independent of which political party or ideology governs Bharata.

Integral decision making seeks to minimize external dependencies and increase our ‘freedom from’ while antifragile decision-making focuses on positioning ourselves to maximally preserve the ‘freedom to’.

We provided evidence in Part-1 that Arthashastra understood antifragility well enough to use it in compatible settings without putting it on a pedestal. I am not rejecting antifragility, which remains an important idea, but pointing to the deeper truth of the Upanishads. Just as (a lack of) vocabulary led to the neologism ‘antifragile’, western languages do not possess equivalent words for key Sanskrit words (termed ‘non-translatables’ [7]) because the integrality of dharma implicit in these terms is absent in western traditions, including the so-called ‘pagan’ ones. However, we do find equivalent dharmic terms within Indic languages like Tamil as explained in our daughter portal article.

The ethics of antifragile decision-making to gain from randomness is derived from the Golden Rule of Christianity [5] that synthesizes common cause for mutual benefit: “do to others what you would have them do to you”. In contrast, the ethics of integrality is, as one would expect, entirely self-contained: Tat-Tvam-Asi [8]. A ‘payoff’ maximizing decision policy based on the former type of freedom (‘options’) yields gains that are ultimately transient but increase long-term fragility whereas the latter (Ritamic decision policy) sheds karmic baggage to progress on the path to Moksha. Reaching the deepest meditative state and the highest level of consciousness is the ultimate state of integrality.

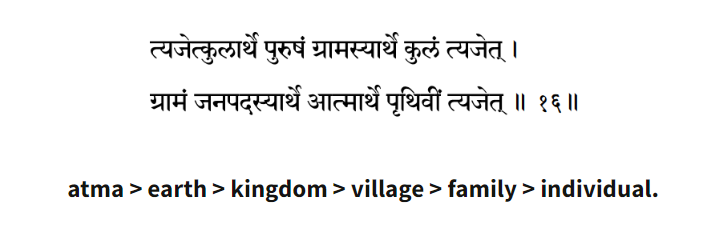

Next, let us see how this integral worldview is used to make decisions in challenging circumstances by returning to the very first quote in this series from the Vidura Neeti [2].

Section-2: Antifragile Pyramid of Synthetic Unity versus Integral Vidura Neeti

“Taking personal risks to save the collective are “courage” and “prudence” since you are lowering risks for the collective [6].

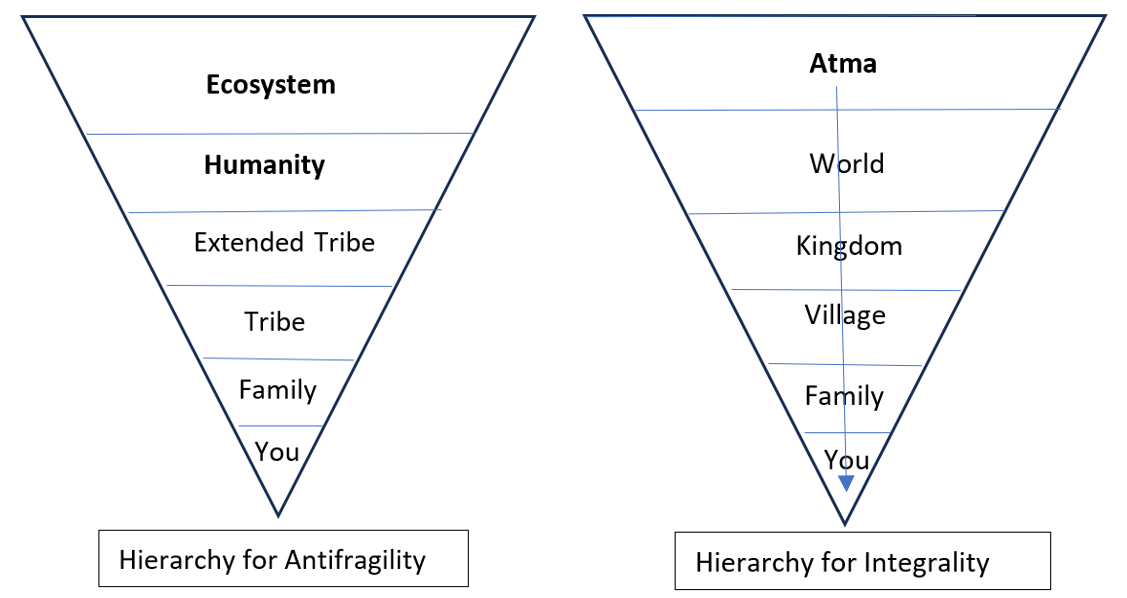

On the left is a simplified depiction of the ‘antifragility pyramid’ given in the book ‘Skin in the Game’ [6]. The idea is that when the entity in the lower-level embraces fragility and nobly sacrifices itself for the sake of the higher layer, the overall system is antifragile. Every layer on the left side consists of fragile material entities from ‘you’ and all the way to the ‘ecosystem’ on the top.

“… the antifragility of the higher level may require the fragility—and sacrifice—of the lower one… consider traditional societies. There, too, we have a similar layering: individuals, immediate families, extended families, tribes, people using the same dialects, ethnicities, groups..” – [5].

This logic holds regardless of how harmful the ecosystem is to those outside. In other words, it is a unidirectional and ‘natural’ transfer of fragility from the top to the bottom to serve and protect a specific ecosystem. Now, a similar idea is presented in the Vidura Neeti of Mahabharata millennia ago [2].

Note how the ‘pyramidal’ representation of Vidura Neeti on the right differs in a crucial way: The highest material layer (‘earth’) is given up for the all-pervasive atma which transcends all other levels and is the most subtle and the most expansive at the same time as explained by the Mahavakyas of the Upanishads. The seamless unity of the adhyatmic and material layers has sustained Bharata and helps it withstand the longest test of time while all other civilizations have perished. Only a civilizational vision that places material gain below the goal of serving every jivatma-paramatma earns the undying mutual respect and support of every kingdom. A village will be ready to sacrifice itself for only those rulers who are themselves willing to give up their kingdom, wealth, and lives to uphold dharma. This dharmic resonance among layers leads to harmony, which is also the essence of Rta.

Vidura’s integral Neeti does not directly prioritize the sustainability of the overall system. What it does is promote the adhyatmic adherence at every level to maximize integrity, which in turn minimizes the long-term fragility of the system. Any social system that lacks this integral bond (bandhu) will inevitably perish.

Let us examine how such an integral approach to decision making has worked for Bharata.

Section-3: Integral Decision Making

Example 1. Leadership: From Arjuna to Hemu to Indian Military Officers

Battles can be won through antifragile positioning, but civilizations are sustained when the decision policy seeks integrality. Let’s discuss the ‘Hemu in the Tent’ question: what would’ve happened had King Hemu as the commander-in-chief decided not to enter the battlefield of Panipat in 1556 and stayed safely in the tent.

If you have a time machine, and you have the chance to go back in time and are allowed to change one thing from Indian History.

— The Kaipullai (@thekaipullai) December 22, 2021

Just one.

What would you change?

I will ask Hemu to be in his tent and not on his elephant in the second battle of Panipat..

This is a brilliant question raised in social media that requires a counterfactual (‘what if’) analysis. Assuming everything else played out the same way in the battle and Hemu was not present on-site to receive the critical wound, that battle would have indeed had the opposite outcome. However, it does not automatically mean that the trajectory of India thereafter would also have positively changed. It may well have been worse. Why?

Rather than view this decision in isolation, Ritamic decision policy (part-4) would ask the policy question: what would be the outcome of adopting ‘Hindu King in the Tent’ as a rule: If the Hindu army won, the king would claim the spoils of war and if he lost, he’d live to fight another day. Such antifragility goes against Vidura Neeti. Any Raja who is unwilling to stake his life when declaring war and prefers to let others fight and die will not enjoy the trust of his Praja and his reign would eventually collapse. As discussed in part-3, Arjuna had to fight and either die and attain Swarga or prevail and enjoy the glory on earth. This is a fundamental lesson of the Bhagavad Gita. Arjuna did not monitor the battlefield from the gallery but put his life on the line every day where a single stray arrow could have ended his life per his karma. This is not just some ancient long-forgotten principle. This integral decision-making tradition is precisely what keeps India safe today.

Few (if any) militaries in the world suffer as high officer casualties as the Indian defense forces. Major Gaurav Arya (Retd.) states that officers form less than 4% of the Indian army but account for more than 12% of the casualties [15]. The Indian military keeps alive the dharma tradition of officers leading from the front and is the core of its officer training. This in turn motivates the NCOs and Jawans to trust the officers with their lives and charge up near-vertical slopes of Kargil to accomplish superhuman feats.

Join me in paying homage to

— Vikas Manhas (@37VManhas) June 28, 2022

MAJOR PADMAPANI ACHARYA CAPTAIN N KENGURUSE

CAPTAIN VIJAYANT THAPAR

on their balidan diwas today.

All three belonging to 2 RAJRIF have immortalized themselves fighting at TOLOLING in KARGIL on June 28, in 1999.

राजा रामचंद्र की जय#FreedomisnotFree pic.twitter.com/0ooyy7ShA1

Kargil was not merely a battle. It is as momentous as any fought by Bharata in the last millennium. The balidan of officers, NCOs, and Jawans alike transformed India from within. The popular claim that ‘New India’ began in 2014 is inaccurate. Sustainable change is never top-down. The seeds of change were planted in the icy lap of the Himalayas and nourished by the oozing lifeblood of hundreds of those Abhimanyus. It is up to us to decolonize from the inside-out and ensure that this is not a false dawn.

Dharmic armies prevail in the long term precisely because every time a Hemu will be found in the battlefield and not in the tent.

Example 2. Development and Lifestyle Choices: Fragile Growth vs Integral Purushartas

‘Small is beautiful’ (SIB) is another concept that has been explained through the lens of antifragility by associating increasing fragility with an increase in size [5]. The eponymous book by Schumacher [12] brings out the fragility of fragmented growth embraced by the West and in that process, SIB makes the case for development that is more in line with the Purusharthas. Integrality has remained central to Indic thought from the Mahabharata to the Yoga of Sri Aurobindo to the modern work of Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya (integral humanism). This principle is also evident in the 2014 IAA speech of Indian PM Narendra Modi.

The extracts from Schumacher’s book below reflect the truth of the purushartas, while noting that his writings were influenced by the economic ideas of practicing Buddhists [14].

“An attitude to life which seeks fulfilment in the single-minded pursuit of wealth – in short, materialism – does not fit into this world, because it contains within itself no limiting principle, while the environment in which it is placed is strictly limited …

If human vices: such as greed and envy are systematically cultivated, the inevitable result is nothing less than a collapse of intelligence… If whole societies become infected by these vices, they may indeed achieve astonishing things but they become increasingly incapable of solving the most elementary problems of everyday existence.

The exclusion of wisdom from economics, science, and technology was something which we could perhaps get away with for a little while. As long as we were relatively unsuccessful; but now that we have become very successful. The problem of spiritual and moral truth moves into the central position. “

The western philosopher-doer’s quest for integrality within their own worldview failed (see part 2) and by the 18th century, the west opted for lopsided growth that yielded rapid material gains accompanied by a collective loss in wisdom and abrogation of personal responsibility at the individual level within their own society; the horrors of colonialism, mass religious conversions, wholesale loot, and genocide for the rest of the world (read The Brush of Dharma).

Today, we come across high achievers in various fields ending up as depressed failures after reaching the pinnacle of material success earned through decades of hard work. It appears paradoxical that they seemed happier during their struggling phase, and it was their ‘success’ that led to their decline. Bharatiya tradition understood millennia ago that any unbounded quest for gain (Artha and Kama) sans dharma is ultimately counterproductive, and this is beautifully explained in the story of the Yaksha’s seven jars.

Example 3. Integrality of Involution versus Antifragile Evolution

Finally, let examine the idea of local antifragility as the basis of evolution.

“.. the most interesting aspect of evolution is that it only works because of its antifragility; it is in love with stressors, randomness, uncertainty, and disorder.

… some parts on the inside of a system may be required to be fragile in order to make the system antifragile as a result. Or the organism itself might be fragile, but the information encoded in the genes reproducing it will be antifragile. The point is not trivial, as it is behind the logic of evolution.

“organisms need to die for nature to be antifragile—nature is opportunistic, ruthless, and selfish.” [5].

Western science and religion both give the prime of place to randomness. The assumption of an objective, pure (metaphysical), non-karmic randomness is widespread across modern STEM domains. Extracts from Prof. Taleb’s book [5] explains how evolution thrives on randomness. By representing nature as a hierarchical system of randomly interacting components, researchers can build useful mathematical models of nature and its evolution by utilizing the latest results from the modern fields of statistics and probability.

Wittgenstein, who understood antifragility better than most, concluded that Darwin’s theory of evolution did not explain the extraordinary diversity of species and questioned the human ability “to understand the whole process which gave it birth” [16]. Clearly, he felt that the modern answers to nature’s puzzle were missing some pieces, which leads to the following question from an Indic perspective.

Is Rta, with its genetic code, DNA, and their chemistry, itself the source and master of all creation and sustenance with nothing beyond? Is there no ultimate reality that is underlying its evolution?

Swami Vivekananda rejects such a Ritam-centric view. Swami ji did not dogmatically reject the modern theories of evolution as false but views them as an incomplete snapshot of what is really an integral whole by stating that every evolution is preceded by involution. The following extracts are from Swami Vivekananda’s discourse on immortality in his Jnana Marga, Chapter 8 [3] delivered in the US.

“There is one thing more, which the ancients perceived, but which in modern times is not yet so clearly perceived, and that is involution. The seed is becoming the plant; a grain of sand never becomes a plant. It is the father that becomes a child; a lump of clay never becomes the child. From what does this evolution come, is the question. What was the seed? It was the same as the tree. All the possibilities of a future tree are in that seed; all the possibilities of a future man are in the little baby; all the possibilities of any future life are in the germ. What is this? The ancient philosophers of India called it involution. We find then, that every evolution presupposes an involution. Nothing can be evolved which is not already there… It was always there, and only manifests Itself.”

If we accept the Vedic assertion of one ultimate reality, then involution → evolution (along with Karma and Satya → Rta) is a consistent and profound explanation (with the exact characterization of that reality left as an open question); if we assert that the material domain is separate from other realms like western science and religion, then involution and integrality get replaced by a dogmatic belief in non-karmic metaphysical randomness. It is worth investigating the last part a bit.

The west has largely viewed uncertainty/chaos/multiplicity as undesirable, to be feared, or conquered so order can reign [8]. In dharma, the seemingly random unfolding of events is simply the uncoiling of what already exists, which impacts us as per our karma. Order and chaos are effortlessly integrated for sustainable decision policy for a better future (parts three, four). Rather than a ‘ruthless and opportunistic’ nature, harmony is the true essence of Rta in dharmic thought [4]. Unsurprisingly, it is Bharata as a society and as a civilization that has demonstrably shown that it is way more comfortable with diversity and uncertainty compared to the west, and Swami Vivekananda explains why:

… As long as you see the many, you are under delusion. “In this world of many he who sees the One, in this everchanging world he who sees Him who never changes, as the Soul of his own soul, as his own Self, he is free, he is blessed, he has reached the goal.

Stand as a rock; you are indestructible.”.

This soul/self that is mentioned by Swami Vivekananda is the atma that Vidura also talks about, and the ‘One’ indestructible reality is Brahman, and the Mahavakyas equate the two. This lucid expression of integrality is Swami ji’s application of the ancient Vedic worldview rooted in Satya and not Rta. This ICP post [4] must be read in its entirety to understand the sheer folly of prioritizing Rta ahead of Satya. It is not just some metaphysical or intellectual point at stake here, for this misplaced priority attacks the very integrity of dharma civilization and dharmikas.

Rta are the recurring transient imprints of Satya across the sands of time, and we can choose to follow these Ritamic footsteps to move ever closer to Satya.

[to be concluded].

Selected References and Further Reading:

- Bhagavad Gita (Chapter 2). Commentary by Swami Mukundananda. https://www.holy-bhagavad-gita.org/chapter/2.

- Vidura Neeti. sanskritdocuments.org, Srimatham.com, and English translation by KM Ganguli.

- Swami Vivekananda. Jnana Yoga. CHAPTER 8.

- Indic Civilizational Portal. Satya, Then Rta, Then Dharma. 2016.

- Nassim. N. Taleb. Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder. Random House. 2012.

- Nassim. N. Taleb. Skin in the game: Hidden asymmetries in daily life. Random House, 2018.

- Rajiv Malhotra and Satyanarayana Dasa Babaji. Sanskrit Non-Translatables: The Importance of Sanskritizing English. Amaryllis. 2020.

- Rajiv Malhotra. Being Different: An Indian Challenge to Western Universalism. Harper Collins. 2011.

- Rajiv Malhotra. Vivekananda’s Ideas and the Two Revolutions in Western Thought.

- Forrest D. Poston. Why Write: Legos, Power and Control. philosophyandnonsense.net. Circa 2012.

- Miguel Equihua, et al. “Ecosystem antifragility: beyond integrity and resilience.” PeerJ, Vol 8. 2020.

- E. F. Schumacher. Small is beautiful: Economics as if people mattered. Blond & Briggs. 1973.

- Nolan Lawson. The collapse of complex software. https://nolanlawson.com/2022/06/09/the-collapse-of-complex-software. 2022.

- Michel Danino. India’s art of simple living- The New Indian Express. 2018.

- Major (Retd.) Gaurav Arya. The Chanakya Dialogues. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DS4E6p-kk0k. 2023.

- O. Drury. The Selected Writings of Maurice O’Connor Drury: On Wittgenstein, Philosophy, Religion and Psychiatry. Bloomsbury Academic. 2017.

- Joseph A. Tainter. “The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press, New York, 1988.

Acknowledgment: Thanks to Smt. Prakruti Prativadi ji and Sri. Nripathi Garu for reviewing the content and their valuable feedback. All errors within this post belong to the author.