In a recent article, we presented a History of Nepal from Legendary & Ancient times to the Medieval Era. However, understanding a people necessitates studying their literature. In this next article, we discuss the Literary Nepali Tradition.

Introduction

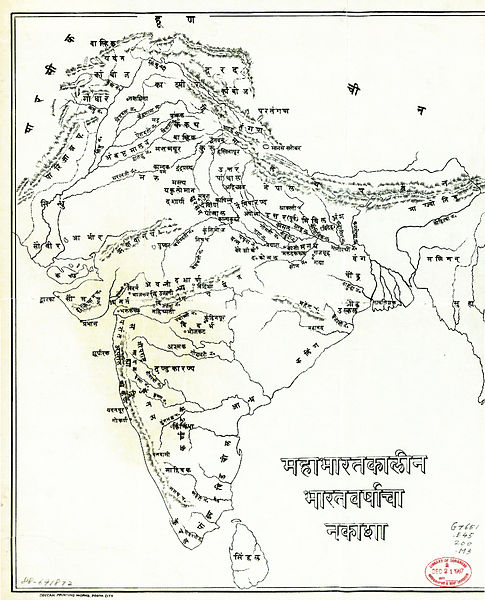

Often forgotten is the ancient place of Nepal, or more Puraanically, the Kiraatha desa within Bhaarathavarsha. Perhaps no story best evokes this notion than the Kiratarjuniyam.

In this epic poem (Mahakaavya) drawn from a famous episode in the Mahabharata, Arjuna fights Siva, in the form of a Kiraatha (mountain hunter). This community has been a part of the periphery of Indic Civilization since time immemorial. Whether they are a modern Indian community (Gorkha) or a modern Indic nation (Nepal), the Kiraathas have a close knit relationship with dharma.

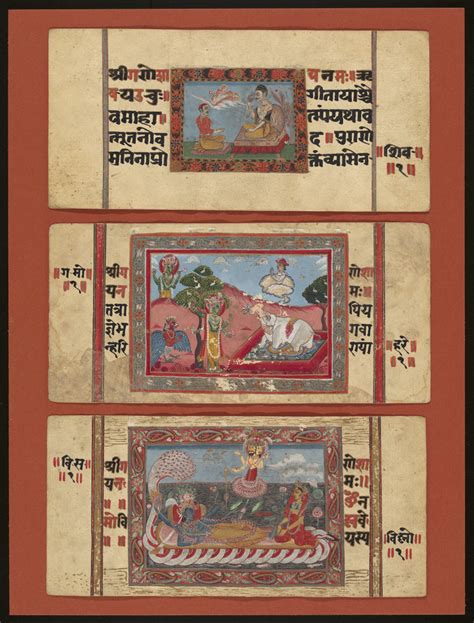

Perhaps one of the foundational works on this connection is the ancillary text attached to the Skandha Puraana, known as the Nepal Mahatmya (Glory of Nepal).

“Nepaalamaahaatmya draws a parallel between Valmiki and Gunaadhya. ‘Both come to Nepal, Valmiki because Naradha, instructed by the gods, pointed out to him, to the north of the hill of Changu-Narayan, the confluent of the two branches of the Virabhadra as the ‘sacred spot worthy to be the cradle of a poem as pure’ as the Ramayana’ Gunadhya, because [S]iva has imposed upon the demi-god of whom he, Gunadhya, is the human incarnation, as condition of his deliverance, after the composition of the Brhatkatha, the erection of a lingam on sacred spot difficult of access; both before leaving Nepal, Valmiki, to return to his hermitage, and Gunadhya to heaven, erect commemorative lingams, the Valmikicvara and the Bhrngicvara.” [2, 413]

Dated to the 10th century, the Nepal Mahatmya is a pivotal puraanic affiliate work that provides insight into Sacred Nepal and its origins. The connection between the Brihat Katha and Nepal is developed in greater detail elsewhere. The author Gunadhya (Gunaaddhya) is destined to go to Nepal in order to established the sivalinga called Bhrgnishvara. Here is an excerpt of the story:

“Gunaadhya is the gana Bhrngin cursed to be born as a human at Mathura. He “sets out for Ujjayini where King Madana, the consort of the learned Lilavati, daughter of the king of Gauda, is ruling. The Pandit Carvavarman, who is in the king’s service, appre-ciates the talents of Gunadhya and obtains for him a place of pandit at the court. Then comes the story of the king’s mistake on the word modaka. Gunadhya asks for twelve years to teach him grammar, Carvavarman only two. There is a bet as in the other version of the legend. Carvavarman wins it… Carvavarman wins it, thanks to the revelation of the grammar Kalapa (Katantra). Gunadhya is condemned to silence; he goes to live as an ascetic in a hermitage.” [2, 416]

The origin of the Brhath Katha is indeed of significant value to Indic Civilization. Many of the stories emanating from it provide key episodes on historical emperors, like the Satavahanas. Elsewhere, it relents to return to the more mystical.

“The ascetic Pulastya passing by, advises him to write his tales in the Paicaci language; he will afte-rwards go to Nepal, erect a linga in honour of Civa and thus obtain deliverance from the curse which has made him a man. Gunadhya writes his poem with minerals on the leaves of trees; as he composes he recites the verses aloud; the wild animals surround him to listen to him and they forget to eat; the game served at the royal table is lean that the king complains; the cooks blame the hunters; these in exploring the woods meet Gunadhya surrounded by the attentive animals; they themselves, falling under the spell, remain to listen. There is no longer any game for the king’s dinner; enraged, he goes to see what has become of the hunters, sees Gunadhya and presses him to come again to Court;

Gunadhya refuses, ‘Sire, I have com-posed 900,000 delightful verses in Paicaci, you must have them written in Sanskrit, as for myself I will go to Nepal.’ He goes to Nepal,sees the Pacupaticvara, then setting forth for the temple of Pacupati he performs around the valley the pradaksina which the Nepalamahatmya describes at great length; it is the guide book of the modern pilgrim. Having returned to the temple Gunadhya gathers all the munis who live in Nepal; establishes the Bhrngicvara and in an aerial chariot (vimana) reascends to the kailasa to resume his place among the ganas. Even at the present day, under the form of a bee, Bhrngin returns, at each phase of the moon to have a look at his linga.” [2, 417]

However, the value of Legendaria aside, the Nepali literary canon proper finds a place in more recent history, with the rise of the Nepali language as we know it today.

History

“Khasas, who spoke an Indo-Aryan language, entered the area which became much later the westernmost part of the kingdom of Nepal.” [1, 6]

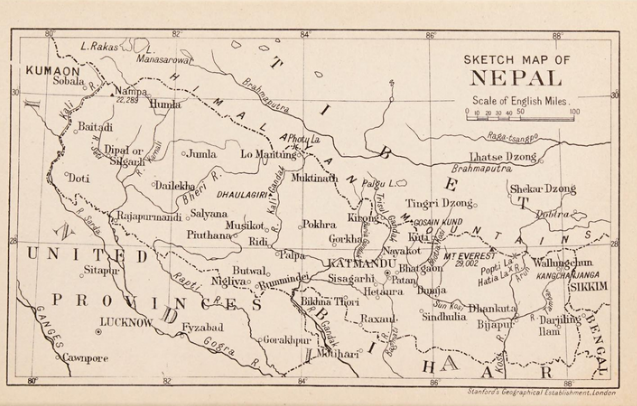

Nepal, historically, has meant many things, before the one thing we know it as. Is it the land of Mithila? The land of Lumbini? The land of the Newaris? The land of the Khasas? Or is it the land of the Gurkhas? These questions become all the more centripetal when one considers that the Nepali is considered an Indian language as well, being widely spoken in Darjeeling.

“The earliest known examples of the ‘Old Nepali’ or the speech of the Khasas occur in a series of epigraphs found there. They belong to Asokachalla (c. 1250), Akshayamalla (1280 A.D.), Aadityamalla (1321 A.D.), Punyamalla (1328, 1336, and 1337 A.D.) and Prithvimalla (1356 and 1358 A.D.) In a Sanskrit in-scription found at Bodhgaya, dated c. 1274, Asokachalla describes himself as ‘Khasaraajaadhiraaaja’ or the king of the Khasa country. The name Khasa appears in many Old Nepali inscriptions of his descendants.” [1, 6]

The period of 1255 and 1533 A.D. “synchronises with the era which wit-nessed the decline and disintegration of the Khasa empire, the advent of the Rajputs and the rise of petty princedoms. The ancestors of Prithvinaaraayana Saaha, the ruler of Gorkha, whose conquests resulted in the forging of a single kingdom of Nepal claimed Rajput descent. They established themselves as rulers in such new princedoms as Dhor, Bhirkot, Satahoo, Garahoo and Kaski.” [1, 7]

Thus, we find the history of Nepali as we know it, closely inter-twined with people from middle India as well. Indeed, the word Gurkha/Gorkha itself originates in the name of Guru Gorakhnath, who provided training for one of the most elite warriors of the Subcontinent.

“Dravya Saaha, a scion of the family, dislodged the tribal chief of Gorkha in 1559 and subsequently this new principality expanded at the cost of its neighbours. His descendant, Prithvinaarayana Saaha, conquered the kingdoms of the Nepal valley in 1768-69 and transferred his capital there from the small township of Gorkha. Thus his enlarging kingdom came to be known as Nepal. His descendants seized more and more territories to the east and west of the Nepal valley and by 1809 the kingdom of Nepal took its present shape. The Khasa speech was spoken in Gorkha. The ascendancy of Gorkha gave a new importance to this language as it came into a wider official use. The language then came to be called Gorkhali by the people of the subdued regions.” [1, 7]

However, the modern madhes is known for its association with the historical Indian region of Mithila, and the trans-Himalayan Nepali-Indian tract is often called “Mithilanchal”.

“Another important kingdom to be conquered by Gorkha was the Sena kingdom which once included large parts of low-lands in central and eastern Nepal. All the extant documents of the Sena kings are in Maithili. The Tibeto-Burman Mongoloid tribes of Eastern Nepal, collectively called Kiraatas, acknow-ledged the overlordship of the eastern branch of the Sena house. Even these Kiraatas used Maithili in their correspondence and many documents survive to bear out.” [1, 8]

This close association bound different ethnic groups not only culturally but linguistically. Khasa, Gorkhali, Maithili, and ultimately Sanskrit became the languages around which the self-anointed “Giri-raaja” or King of the Mountains, would express himself.

“Previously Nepal denoted only the Kathmandu valley and ‘the language of Nepal’ meant Newari, Newars of the valley often use the name ‘Khay-bhay’ or ‘Khas speech’ for Nepali.” [1, 4]

Language

“Nepali is a kind of a lingua franca used widely through the Himalayan area.” [1, 1]

From the history of language in Nepal to the history of the Nepali language, one traverses a meandering and misty path at comprehending comprehension in these Kailaasan clefts.

“The History of the Nepali language can be traced back at least form the early part of the thirteenth century A.D., as evinced by a num-ber of epigraphs; that prose writing in Nepali began earlier than in many other modern Indo-Aryan langauges; that constraints stunted in general the growth of Nepali literature; yet that its achievements in different genres–are facts little known to many.” [1]

As mentioned previously, the sway of Nepali runs far past the modern boundaries of the political state. This is less due to conquests and more due to the widespread economic migration of gorkhas and other ethnic nepali peoples.

“Nepali is a modern Indo-Aryan language and is widely spoken in the state of Sikkim, the northern districts of West Bengal, many pockets of north-eastern States, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, and its speakers can also be found in many major towns and cities of the country.” [1, 1]

“A number of similarities between the languages spoken in the lower Himalayas from Nepal to Chamba led Bains to call them ‘Pahaari’ or ‘Mountaineers’ Language. It has been sub-divided into three groups, namely, Western Pahaari of the Punjab Himalayas, Central Pahaari of Garhwal and Kumaon and Eastern Pahaari of Nepal. Eastern Pahaari is another name for Nepali.” [1, 4]

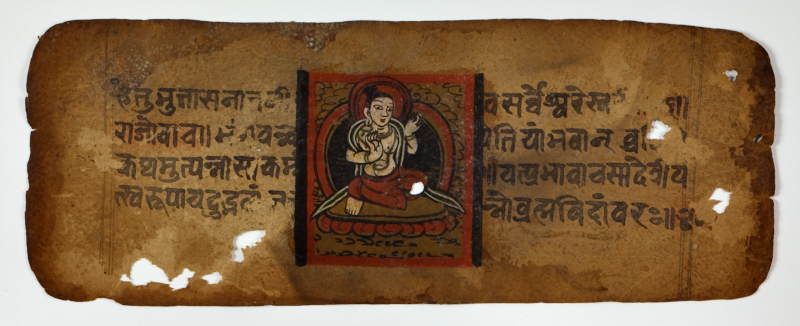

Brahmi and Devanagari, nevertheless, remain the traditional scripts of Nepal.

“As far as the orthography of the language is concerned, the devanaagari alphabet seems to be in use from the very beginning. Though Newari was written in as many as nine different scripts, all derived from Brahmi, the Khas-Kuraa, or Parbate was written in devanaagari. ” [1, 11]

“The North Bengal University is the only university in India which offers Nepali as a subject for study in honours and post-graduate courses.” [1, 225]

Literary Tradition

The literary tradition of Nepal draws much from the fount of the Classical Indic Canon. From the Nepali Ramayana to the Nepalamahatmya, one finds the inter-linking of India proper and the Indian frontier to be multi-farious. And yet, while Kiraatha desa is old, the Nepali literary tradition is comparatively new.

“For years Nepali remained as a reflex of Sanskrit literature. The classical language was patronised by the rulers of different principalities. Though Nepal produced many eminent scholars, only a rare few of them wrote in Nepali also. The spread of Nepali as the most important language not only in Nepal but also in other sub-Himalayan areas was a historical fact.” [1, 226-227]

The last millennium, proved to be pivotal to this once provincial language. Its native scholars would accumulate artefacts and analyse their origins.

“Baalkrishna Pokhrel collected and edited the specimens of the Nepali prose of five hundred years from 1336 to 1866 A.D. in his Paach Saya Varsha (Five Hundred Years, 1963)…The epigraphs dating from the late thirteenth century show that Nepali was a fully developed language by then. Many words in them look strange but to one who knows modern Nepali the language does not sound foreign.” [1, 25]

Nevertheless, Royal patronage (as always) would become instrumental to the preservation and propagation of this bhaasha.

“If the use of Nepali for administrative purposes appears from the thirteenth century, its role as a medium of literary expression can be traced only from three centuries after. A short biography of Raam Saaha (c. 1606 A.D.), the king of Gorkha in the early seventeenth century, is often regarded as the first non-epigraphic prose writing discovered so far. But its language appears to be comparatively modern.” [1, 25]

“Prithvinaaraayana Saaha’s maxims, now published under the title of Divyopadesa (Divine Precepts), is an important work of the period. After his conquest of the Nepal valley in 1769 the king is said to have taken respite and laid down guidelines for the future polity and economy of the kingdom. His oral direc-tions are said to have been taken down by his renowned com-mander Sivaraamsingh Basnet.” [1, 26]

Other notable high culture works include the 1776 Bhanudatta’s translation of the Mitralaabha portion of the Hitopadesa. Then there is the Lakshmi-Dharma Samvaadh or Dialogues between Lakshmi and Dharma in 1794, by Raambhadra Paadhya. “More renowned was Saktiballabh Aryaal, a scholar at the court of Prithvinaaraayana, who besides being the author of a Sanskrit drama Jayaratnaakara Naataka is now re-membered more for the literary value of the Nepali translation of his other Sanskrit work, Haasyakadamba (Flowers of Laughter, 1798).” [1, 27]

Nepali Literary Forms

“Compared with prose, the history of Nepali poetry is of much later origin…Folk ballads, songs and stories contain some vestiges of more ancient literary products. Nepali indeed has a rich heritage of folk literature having a perpetual charm.” [1, 226-227]

From laharis to bhajanas and beyond, there is a plethora of literary forms in Nepali poesy and prose. Other than the aforementioned, is the famous all-India one:

“Kavitta is another form of versified composition which con-tains a heroic tenor and also suggests the oldest form of Nepali poetry.” The most popular kavitta khaado jagaaune, the one which invokes the sword” [1, 18]

There are, along with riddles the common literary form known as idioms, which are called tukkas in Nepali. [1, 21] Related to tukkas are the proverbs or ukhaans, which number in the thousands. Here are a few samples:

“Arkaako aas nita upavaas

One who depends on others will have to fast for ever…

Ausar auchha parkhadaina

Opportunity comes but it does not wait.” [1, 22]

Then, there is the every popular prose form, known as Gadhya Kaavya in Classical Indic Literature. Here, there is a massive list of works that draw directly from the common, trans-himalayan canon.

Sanskrit Literary Influences

“Nepali prose appears to have developed then more in translations from Sanskrit. Among the important works of early nineteenth century we have Daivajna Jyotinarasimha’s Tulasi-stava (1809), an anonymous translation (1818) of Dandin’s Dasakumaaracharita, Vijayaananda’s translation of the Gadaa-parva from the Mahabharata in 1829 and Bhavaaneedatta Paande’s render-ings (pre-1835) of Visaakhadatta’s Mudraaraakshasa, Aatmabodh, some portions of the Mahabhaarata, Maarkaandeya Puraana and Hitopadesa. Bhavaanidatta’s works were literally retrieved from a dustbin where they were thrown by his descendants.” It is sug-gestive of how many old manuscripts must have met with similar fate.” [1, 27]

Elsewhere, one may find the direct incorporation of Sanskrit metronymy in both poetical and practical literature alike.

“Daivajnakesari Aryaa’s Gorakshaayogasaastra (1820) is a prose work which ends with two stanzas. A treatise on the good and bad characteristics of horses called Asva-subhaasubha-pareekshaa has recently been discovered and its authorship is assigned to him. Its eighty-eight stanzas are composed in a number of differ-ent Sanskrit metres, namely, Totaka, Svajaati, Saardoolavikridita, Maalini, Upajaati, Vasantatilaka, Sravini, Bhungaprayaata, Upachitra, Sragdhara and Bhadrika.” [1, 31]

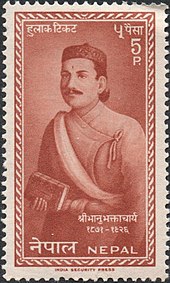

The use of Saardoolavikridita and Sikharini is considered to be a notable trait of Nepali literature. The acme of this trend and indeed, Nepali literature itself was the most prominent author of this genre: Bhanubhakta Acharya. His Raamaayana would animate and proliferate throughout Nepal.

There are of course, many, many more works and authors, but they begin to spillover into the era where Nepal’s near-protectorate status vis-a-vis the British Indian Empire began to have noticeable effects. Everything from the introduction of Christianity to the rise of Revolutionary and even Marxist literature, influenced the drama, poetry, and prose of the period. That is a matter for another time.

“If Hindu mythology and Sanskrit works inspired indigen-ous writings, Christian missionaries were not lagging behind in the task of acquainting Nepali speakers with the Christian scriptures. The full text of the Bible was brought out from Serampore in 1821 and one year before J.A. Ayton’s first Nepali grammar in English with Nepali words printed in the devanaagari had been published from the Fort William College. However, the credit for the first full book to be printed in Nepali in the devangaagari type goes to the Serampore Bible”. [1, 28]

As one will see in a future post on the topic, much of the distancing between India proper and Princely Nepal is a product of Post-Modern and Modern Global influences. Free thought also means foreign thought and foreign ideas, which also influence once bound brothers to begin to bend towards newer, non-newari/non-mewari friends.

But why try to rephrase what is composed better by others:

“The birth and growth of Nepali took place in Bhaaratvarsha or the Indian sub-continent long, long before the emergence of political India and political Nepal of today.” [1, 2]

Selections

The selections from the Nepali Literary Canon could run the gamut. However, Early Modern and Post-Modern Nepali literature could be another article in and of itself. Instead, these selections focus more on traditional Nepali literature. It is traditional in the sense that it is not at the cutting edge, but rather, at the cultural beating heart of the Nepali people and their civilizational heritage: “For a better understanding of the history of its origin and development, we may begin by posing the question, ‘Why was Nepali generally known as Khas-kuraa or the speech of the Khasas till the last century?’ The nearest relatives of Nepali are Kumauni and Garhwali, spoken in Uttar Pradesh [Uttarakhand] in the im-mediate western vicinty of Nepal.” [1, 3]

§

Perhaps the first literary form worth considering as a selection is the most simple: the riddle.

“Questions posed in these riddles are marked for the brevity and artistic use of language which tease and stimulate the brain and imagination of children:

Bhu bhu garchha bhamaraa hoina

kaadhmaa janai baahun hoina, ke ho?

It hums but is not a bumble bee,

It wears sacred threads, but it is not a Brahmin, What is it?

(The answer is charkhaa or spinning wheel)” [1, 20]

§

This next selection is from Jnaandil’s Udaya-Lahari (1877). The Lahari was a form of short poem common in Nepal.

“Ain bajryo dhaniko firyo jagamaahaa

Ghusyaahaa bhichaaree nisaap herchha kaahaa

Ghusyaahaa bichaaree jagatamaa firchhan

Dhana bhannyaa Saadhu jaani jaani girchhan

Laws are made for the rich, such appears the universal rule,

From judges taking bribes none can get justice.

There are men in the world who are untrue:

Like [sadhus] who run after wealth,

Be sure, they will fall down the precipice.” [1, 63]

§

“Daakmaan Rai, a constable in the police force [Darjeeling], has this to say of the British Raj:

Dhanyai raichha sarakaar chaar varna paalne

Dhanko laalach dekhaaee haad maasoo gaalne

Angrejko yati dharam bado khubai maane

Duniyaalai fakaai fakaai bal baeesa khaane

Bravo to the government which keeps four varnas in shape

And tempting with money our bones and flesh does take;

This is the trait that the English have, I know,

By wooing, others lives they swallow.

He was equally critical of the businessmen from the plains whose wont he describes was to cheat the simple hill folk“. [1, 159]

§

“The Nepali Brahmins are not supposed to plough the land. But land was the sheet-anchor of economy, the source of all wealth, power and prestige, and the priestly caste, bringing more and more land under it by various means, was turning to be the class of land-owners and rich agriculturists. In the bhajan written jhyaayre, Jnaandil sang:

Kalikaa Brahma jati satamaa giryaakaa

Halo chha piyaaro Veda naparnyaa

Bhakti nindaa chhodi aafnu karma garnu

Dasai karma chhodi halo maathi dharnu

Kaadhamaa halojuwaa goroo chhan kaahaa

Badaa hoo haamee bhanchhan naraloka maahaa.

The Brahmins of this Kali Age are fallen from Truth,

They don’t read the Vedas, the plough is dear to them.

Ignoring all their duties, loaded with ploughs and yokes like oxen, They still think they are superior to all men.” [1, 65]

§

“But language, religion, culture and thought transcend political frontiers. Bhaanubhakta Aachaarya, the Nepali national poet who took his birth and died in Nepal, wrote:

Barho durlabha jaanos Bharatabhumiko janma janale

Let people know it rare to be born in Bharat-land

and Lakshmiprasaad Devkotaa, regarded as the most significant poet of modern times in Nepal, sang:

Meetho laagccha malaaee taa priyakathaa praacheena Samsaarako

Haamraa Bhaaratavarshako udayako haimaprabhaasaarako

Dear are to me fond stories of the ancient world,

Of our Bharat, of her rise, shining forth as sno-glow” [1, 2]

References:

- Pradhan, Kumar. A History of Nepali Literature. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. 2020

- Krishnamachariar, M. History of Classical Sanskrit Literature.Delhi: MLBD. 2016

Editor's Note: All emphasis ours in quoted paragraphs.