The name of Mewar brings to mind heroism and desert valour. But the land of the Aravalli mountains was known for more than just its history or even aridity. To sustain any kingdom, indeed, any state or country, agriculture is required.

“Mewar’s contribution to agriculture can best be understood through its water bodies, lakes and water management systems. Udaipur till date is known as the city of lakes.” [2]

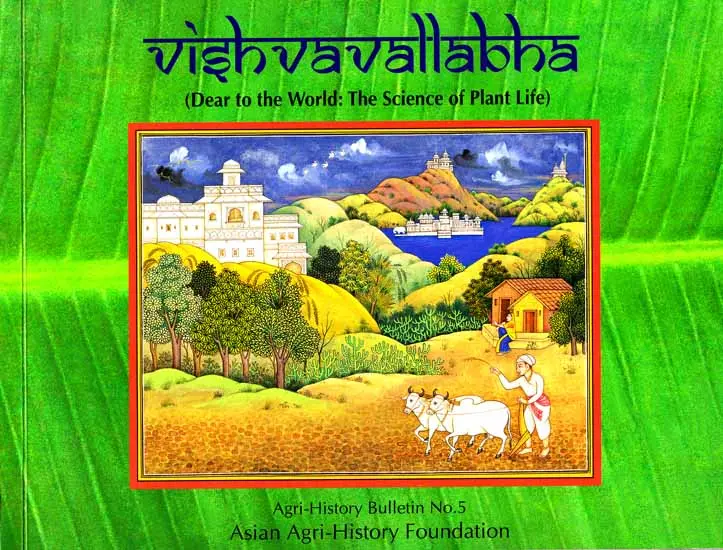

Scarcity begets necessity, and research into the realm of agriculture was furthered through the trials and tribulations of Rajputana’s most famous state. The Vishvavallabha by Chakrapani Mishra was the result of this circumstance. Despite being composed in the 16th century, and being one in a long line of works on the topic, it was rather advanced in its study of the topic of horticulture.

“What is amazingly admirable is its focus on science and technology; its fullest utilisation through the establishment of several departments.” [2]

Author

To properly understand a work brings to bear the need to understand the author. The Vishvavallabha’s composer was a learned man of respected lineage.

” Chakrapani Misra was the Court Pandit of Maharana Pratap. He was a Mathur Brahmin and belonged to the Nasavare Chobe family, Dr BM Jawalia writes in a 1989 volume commemorating Rana Pratap. Misra was the ancestral title for the family, which had served the Ranas of Mewar. ” [2]

Indeed, Chakrapani came from a long-line of scholars attached to the rulers of Rajputana’s leading kingdom.

“His great-great-grandfather Ashanand served in the court of Maharana Kumbha as Purana-vacaka in the 15th CE; his son, Sukhdev was also at the same post. Gajadharin, the next generation is a scholar honoured by Rana Raimal. Ugra Misra is his son, another well-respected scholar, to whom Chakrapani Misra was born.” [2]

It is said that Maharana Pratap himself directed Chakrapani Mishra to research and compose a manual on the welfare of plants and crops, or more correctly, Vrkshaayurveda.

“During his reign, Maharana Pratap developed Chavand as his capital and his kingdom flourished from 1586 until his death (19th January 1597). Maharana Pratap protected his own honor as well as that of his people all throughout his life“. [1,v] One such personage was the author.

Other manuals were also attributed to Chakrapani. These were Rajyabhishek Paddhati, a work on Royal Coronation Ritual, and Muhurthamala on Astrology.

“Chakrapani was well versed in the Vedas, the 6 systems of philosophy, and also other religious treatises and several branches of science.” [1, vi]

Maharana Pratap “had forbidden farming on level lands and had ordered his farmers to cultivate only hilly regions for providing food to his army and preventing Akbar’s army from having an access to the same. It also prevented the Mughals from looting and destroying crops. These circumstances could have prompted the king’s specific request.” [1, 99]

What has been increasingly lost is this benign and sattvic attitude and mentality possessed by brahmanas, who humbly served their dharmic patrons. Rather than take credit for the reigns of rajas (like many revisionist historians do today), they credit their king with encouraging them to take up areas of learning, as Chakrapani Mishra does by his own written statement. [1, 96] This is done not for award, aggrandisation or exposition, but for contribution to the welfare of polity and society-at-large. Rather than ruling-by-proxy as Chanakya with Chandragupta, this is actually what is meant by brahma and kshatra going hand-in-hand. Knowledge is a spiritual undertaking for the material and spiritual benefit of others.

“Historians of science have commented that brilliant minds like Chakrapani Misra were trustees of knowledge, highly respected by peers and juniors, assisted by scholars contributing to the development of knowledge. ” [2]

Composition

Vishvavallabha is loosely translated as ‘Dear to the World’ and is a composition on the Science of Plant Life. [1]

“In the midst of struggles against the Mughal Empire in the 16th CE, Chakrapani Misra undertook the task assigned to him by Rana Pratap to prepare a treatise on various branches of learning and science. In 1577 CE, he composed Vishwa Vallabha in Sanskrit, as was the norm of the age. “[2]

Though certainly not the first to write on the topic of Vrkshaayurveda, Chakrapani Mishra’s opus stands out for a number of reasons, not these least, its methodical nature.

“Its nine chapters reveal that it deals with examining the ground for water, rules for ascertaining sources of water on the basis of types of soils, rocks and vegetation, digging of wells, step-wells, ponds and tanks, methods of blasting hard rock, equipment used in digging wells, methods of purification of sour and hard waters, and analyses of soils and plantations. Soon enough, the 16th CE treatise begins to read like a manual on agri-extension services prepared by a Ministry of Agriculture in the 21st CE!” [2]

The manuscript itself is found in worn and somewhat corrupted condition at Jodhpur, and is a copy dated to the 19th century. [1, 102]

“The entire composition is in verse form except the subtopics, which are designated in prose. The writer has very good command on long meters like Sragdhara, Shardulavikridita, Prithiv, and Mandakranta, which he has frequently used throughout the composition“. [1, 102]”The author makes a passing reference to plants brought from foreign lands but discourages their plantation.” [1, 101] “The verses describe construction of lakes for villages and pleasure resorts for kings, ponds, wells, and potholes. Besides, some verses explain the techniques for breaking rocks and for preventing damage to implements.” [1, 109]

What is intriguing about the treatise is the continuity of its more practical aspects. Specifically, one sees usage of the exact units of measurement that were stipulated thousands of years ago in the Arthasaastra. Units such as hastha and aadaka are staples of Pauthavam, and utilised copiously in the Vishvavallabha. “A good deal of this information apparently was taken from Brihat Samhita of Varahamihira“. [1, 110]

There is also mention of gardening. “Verse 8 suggests that for developing a good garden the land should not be under ripe grass, mash…and tila…This probably was because of the grain shattering varieties of grasses, mash, and tila, which could create a continuing weed problem.” [1, 111] A notable point was that fumigation is also suggested through the use of the neem tree’s bark. [1, 113]

Indic texts on Agriculture have been previously discussed, such as the Krshi Paraasara and Lokopakaara. Separately, the Indian knowledge base of arbohorticulture can be traced “from Atharvaveda through Agnipurana, Brihat Samhita, Surapala’s Vriksayurveda, Upavana-vinoda to Vishvavallabha.” [1, 114] Here are selections from the oeuvre at hand.

Selections

I. “Having saluted the lotus like feet of Shri Raghavendra as also those of my preceptor, I shall expound the everlasting knowledge on water and also the technique of planting, etc., of trees, depending on it.

How much water is available underneath the ground? What are the indicative signs to find it and at what depth…is it available? In which direction do the currents flow? Is there an obstruction of a rock, etc.,? Is the water sweet or otherwise? Is there sand underneath? —This and all that which is conducive to the welfare of mankind, I shall impart now narrate after consulting the sciences, which impart everlasting knowledge.” [1, 58]

§

II. “A village where water current underneath does not exist even within the limit of thousand dandas (where a danda is a measure of length equal to four hastas) in directions stated to be auspicious for constructing wells, a well situated in an inauspicious quarter too, does not lead to misfortune. It may be used for watering trees, etc., without any harm.” [1, 68]

§

III. “If water of a well is saline, khadira used with churna (chalk powder), turns it into a desirable taste. If it is turbid, it can be purified with palashabhasma” [1, 69]

§

IV. “A lake is stated to be superior when measuring a thousand dandas (1.8 km) (1 danda= 4 hastas, 1 hasta = 1 forearm = approx. 18 in or 45 cm) in length. It is mediocre when the length is half of that and inferior when the length is half of that of the mediocre one. Depending on the room available, they are indeed big or small.” [1, 67]

§

V. “If a dam is constructed between two hillocks or if an extensive land lies in front of a mound, a huge lake, a tank or reservoir always having a plenty of water can be constructed in the basin at a low cost.” [1, 67]

§

Click here to Buy this Book!!!

References:

- Sadhale, Nalini & Y.L.Nene. Vishvavallabha. Secunderabad. Agri-History Foundation. 2004

- Mansukhani, Raju. ‘Chakrapani Misra: Ode to a forgotten man of science’. DNA India. June 18, 2019