In an age of Navic Satellites & Unmanned Amphibious Vessels, it becomes difficult to appreciate just how impressive ancient Navigation used to be. Particularly in a post-modern India that unquestioningly accepts modern technology without valuing the practicals of the past, knowing the value of the ancient arts can often be a tall order.

And yet, Naava Sastra, i.e. Indic Shipping & Navigation is nearly forgotten. Though elements are discussed here and there in sections of the Arthasastra or in dicta of the Mahabharata, the reality is the Indic Art of Shipbuilding and Sea-travel was indeed standalone.

Introduction

Ship-building and navigation has long been an essential part of commerce. Not only seafarers, but riverine boatmen and lake ship-owners are not unknown even today (see the famous Dal Lake and its Shikara boats). However, it is the brave captains of the sea who have historically inspired imagination.

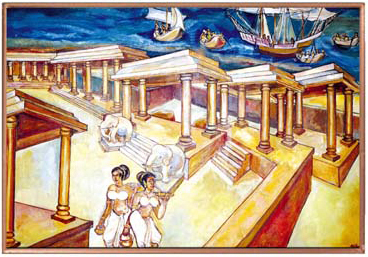

From Bhrgukaccha to Arikamedu to Kalingapatnam to Tampralipti, ancient India had many storied ports (pattana) and many fabulous merchant-seafarers. Later still, the Andhra Satavahanas famously struck coins with images of their ships, and Pallavas and Cholas expanded into the Lakshadweep, Andamans, and South East Asia. The Brahmin Kaundinya is credited today with his own ship, having been the historical merchant explorer who established an Indic alliance with the local Cambodian princess. The names Kambhoja, Sri Vijaya, Yava (Java), and Suvarna (Sumatra) are all sprung from this Indic influence, which was mainly cultural and commercial and rarely colonial (in the modern, de-humanising sense). [4, 479 ]

During India’s own colonial era, European sailors were routinely astonished at the size and innovation of India’s ships (which often reached 1500 tonnes displacement). Despite the decline in Dharmic power, the Maratha empire would establish a powerful navy (established by Shivaji Raje) that would challenge Colonial ships ’til the very end.

It was the Indic tradition of Ship-building and Navigation that made it all possible. And while modern science and engineering has far and away outstripped the traditional craft, the best sailors & practicioners are those who first learn the traditional way, then cutting-edge way. After all, if everything even your thinking can be outsourced to AI & “Google devta”, soon you will be too.

That is the imperative of studying the antediluvian tradition of Indic Ship-building and Navigation.

Terminology

- Vahithra—Ship

- Naava/ Plava—Boat

- Nauka—Skiff

- Sanjatya Naava—Ocean-going vessels

- Prabhancha—Coastal vessel

- Mahandrahs—Large riverine vessel

- Krudraka Naava—Small river boats

- Svatarnam—Private ferry boats

- Himsarika—Private ships

- Pattana—Port

- Nangara/Nagarasila—Anchor

- Mandhira—Cabin

- Anithra/Dhanda—Oar

- Phalaga—Plank

- Rajju/Soothra—Rope/Rig

- Karna—Rudder

- Patha—Sail

- Panipala—Sail cloth

History

“The sub-continent of India has a rich maritime past and heritage. India or Bharat owes this rich heritage to the advantageous, central geographic location of the Indian peninsula, surrounded on three sides by the vast expanse of water” [1, 1]

The History of Indic Ship-building often commences with stray mentions of boats and sailors in the Rig Veda and Satapatha Brahmana. However, most archaeologists commence with the Indus Valley Civilization, known to us today as the Sarasvathi-Sindhu Sabhyatha.

“How old is the maritime heritage of India? The fact that Indian products like ivory, ebony, muslins and sandal-wood were found in the Great Pyramids of Giza belonging to the third and fourth dynasties of Egypt points to the entry of Indian produce into the valley of Nile at the height of the Egyptian Civilization through overland routes or more likely the sea-route.” [1, 1-2]

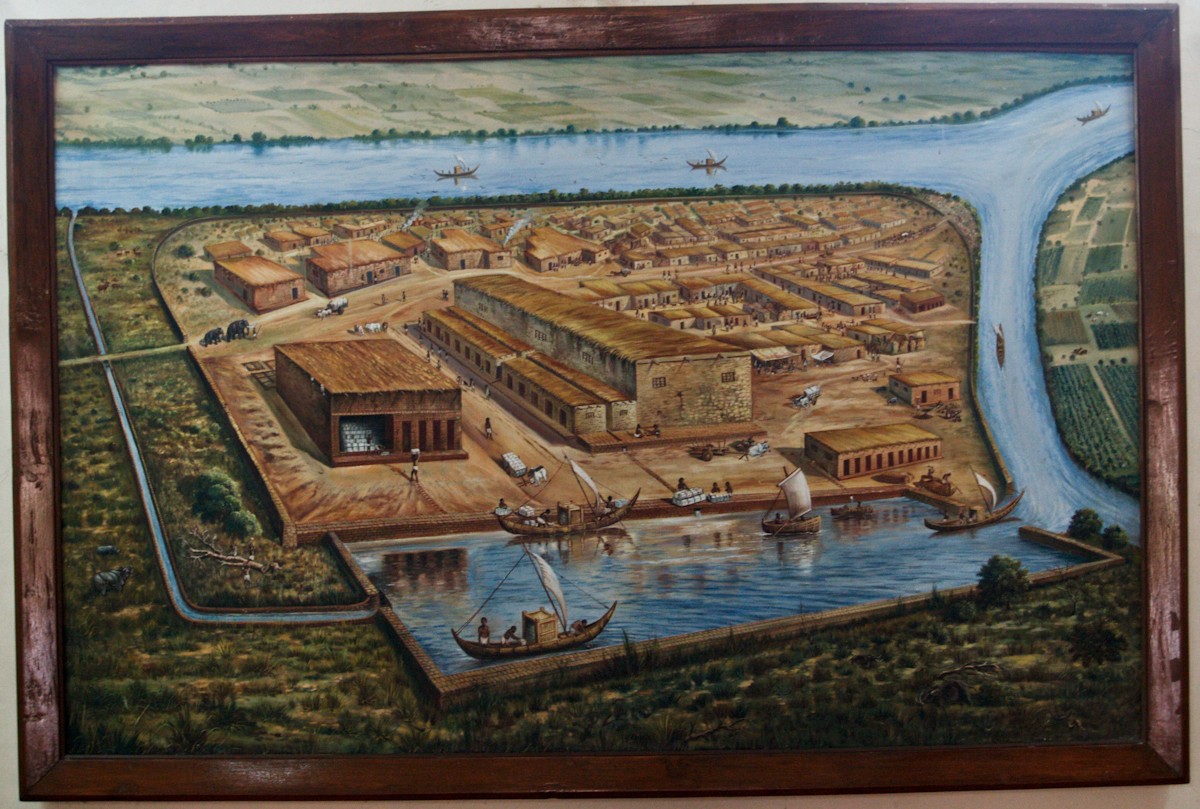

“A number of port sites of the period have been identified: Lothal, Prabhasa, Todio, Dwaraka, Navinal, Kanjetar, Hathab, Mehgam, Bhagatrav, Surkotda and Dholavira. G.F. Dales relying on the excavations at the port sites of the Gulf of Khambhat and Kutch, belonging to the Indus Valley Civilizations, states that these ports were engaged in the ‘highly organized ea-trading ventures’ into Mesopotamia and other regions in the West. The Sumerian clay tablets indicate that the maritime water crafts were’ exceedingly large at the time of the Egyptian Third dynasty, possibly a size of 100 tons’“. [1, 2]

Not only is there plentiful evidence for the construction of reed boats and lateen sails, but even soapstone seals from Lothal Merchant guilds found in Mesopotamia. There is a very antique history of Commerce between the Indian Subcontinent, Mesopotamia, and Egypt. These ancient civilizations were influenced by and influenced each other. Indeed, coastal and commercial people are almost always the most cosmopolitan. Unlike their inland and insular co-ethnics, they often find common cause and interest with the more humanistic peoples of the international sort. In a world filled with hidebound tribalism, it is the humanists (secular or dharmic) who often think more about the benefit of all humankind, rather than merely their own clansmen or “klan”.

This awareness of the wider world and interchange with it, results in a duality in the Indic mind. On the one-side it is highly regimented and rooted in the land, and on the other, noted for some of the most commercial and internationally enterprising people on the planet. Perhaps this was due to the manifold nature of the over-discussed varnashrama dharma. The much-maligned “bania” of today, was once respected as the Dharmic vaishya and vanija of old. He who earned money honestly and gave charity generously, was naturally appreciated. Even the Buddha appreciated the munificence of merchant-men like Anathapindika.

“Many Buddhist Jataka tales give interesting accounts of sea-voyages in the Ratnakara (Arabian Sea) and the Bay of Bengal. The Surparaka (Sopara) Jataka attributed to fifth century B.C. talks of a Bodhisattva steersman helping a group of merchants on a sea voyage. Being a master navigator, he was not only an expert in orientation of the boat direction in relation to stars, but also in estimating location in the open sea and with reference to the colour of the sea-water.” [1, 2]

“The earliest historical representation of a boat belongs to the Buddhist monument. The Bharhut bas relief of the 2nd century B.C. shows a boat attacked by a sea monster. The canoe of the Sanchi sculpture also belonging to the 2nd century B.C. is on the eastern gateway of the number one stupa….The sculptures in the caves of Kanheri at the fringe of Brihan Mumbai (Greater Mumba) belong to 2nd century AD. There is a representation of a shipwreck, and the voyagers praying to god Padmapandi.” [1, 35]

For this reason was there not only an Artha Saasthra, but also a Naava Saasthra. This scripture of shipbuilding is mentioned elsewhere as Nauka Saasthra. “A Sanskrit work by name Nauka Shastra is believed to have existed in the past. At present it is not traceable. There is a tamil palm leaf manuscript in Col. Mckenzie’s collections in the Tamilnadu State archives by name Navoi Shastra. This text seems to have been handled by many amateurs who have to a large extent mutilated and damaged the work. This work appears to have been authored by Trikuta Nambi and completed in A.D. 1502“. [1, 55]

However, that wasn’t the only text type. There were others which made their impact directly or indirectly as well. “An early Sanskrit work, named Vriksha Ayurveda or the science of plant life or botany talks of four different types of wood for a variety of timber uses. The Brahmin class of wood is light and soft and can be easily joined to other timber. The Kshatriya class is light and hard but cannot by joined to any other class of timber. The wood that is soft and heavy belongs to the Vaishya class and the Sudra wood is hard and heavy.” [1, 55]

Bhoja Paramara was a great King, commander, and polymath. He was a unique confluence of manliness and intellect that is lacking today. His widespread understanding of manifold areas permitted him to not only draw from Naava Saasthra, but apply to his own military.

“A compilation by Bhoj Narapati of twelfth century, under the name Yuktikalpataru makes use of this caste classification of timber of the earlier text and gives significant warning to ship-builders that no iron should be used in holding or for plank joinery, since the boat will then be exposed to magnetic influences at sea. The boats have to be niloham. The text goes further to classify the boat forms which will be discussed in later chapters.” [1, 55]

“The Yuktikapataru states that the best wood for boat timber is of the Kshatriya class and that mixing of woods of different classses and castes is not desirable since such a boat built of mixed wood will not last long and will rot fast. But the later day Navoi Sastra and Kappal Sattiram talk of using a variety of timber in combination in a boat, based on their specific qualities of suitability for specific boat components.” [1, 59]

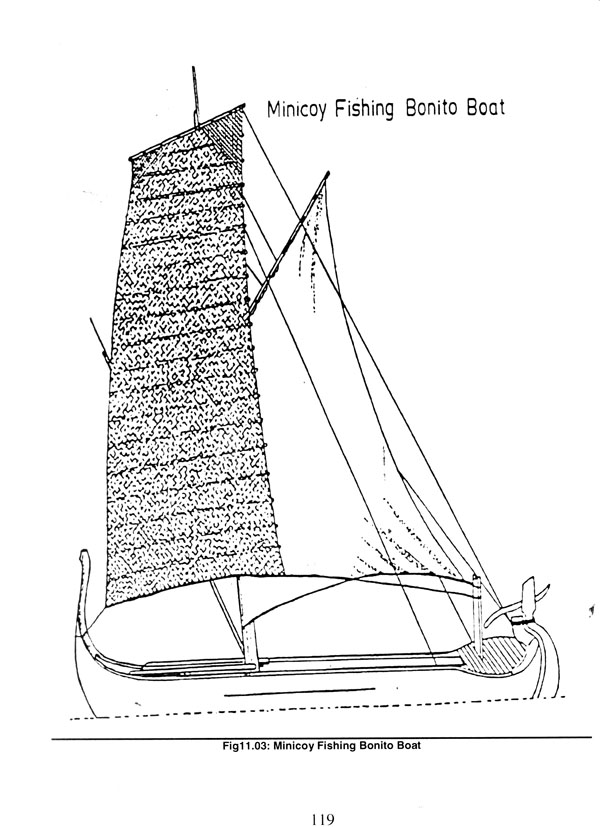

Despite the somewhat antiquated classification system, ancient Indians had a keen eye for the wood of the keel. Teak wood is considered the best, though it was generally not used for Keel and Hull due to floating limitations. Jack fruit, mango, neem, and aini were other favourites. Timber defects are warned against, especially bores due to insects and fungal infestations. Damp wood is to be avoided for this reason. [1, 59] These and other aspects can be discussed later.

Returning to the history of Indic Ship-building and Navigation, one finds the progress from the reed vessels of the Indus valley to the war-boats of the Vedic period, to the mature and sometimes massive vessels of the medieval with 600 tonnes displacement.

Although, sculpture and painting provides some insight into the seafaring capability of ancient India, it is accounts of war that often provide deeper insight.

Perhaps the most famous Naval battle was one that acted as a feint. Alexander of Macedon recorded that his invasion of India was preceded by 2 others (Cyrus & Semiramis), and both ended in failure (Indians assert that so did Alexander’s). Regardless, Semiramis is said to have battled with the Indian King Stabrobates on the Indus river. Though her Imperial naval vessels were triumphant on the river, her army was drawn in to the Eastern Bank of the Indus and ultimately defeated by the Indians. This is the first recorded “historical naval clash” in India.

“With the dawn of the historic era, during Mauryan times, a great voyage took place in the Bay of Bengal known as Bali yatra. this voyage took hundreds of Kalingans from the coast of Orissa by coasting to Kalingan Turai in the north of Srilanka, from wherethe voyagers proceeded gurther east aross the southern Bay of Bengal to Java and Bali to settle in those areas. Even today, Indian migrants are called ‘Klings’ in Bali.” [1, 3]

Elsewhere, the Burmese of Bamar desa (Brahma desa) had countless commecial links to Andhra. This was the case to such a degree that the native Bamars/Myanmas referred to Indians as Tailings (from the Telugu-speaking Telinga desa). The Ubhaya Saasana of Maharaja Ganapati Deva Kakatiya protected commerce from around the world, at the great port of Motupalli.

Returning to the Arthasaasthra, there is mention of the “Navadyaksha, and other naval officers, posted at the ports. He appears to have been a sea-customs official. A class of navigators, sailors, ship-wrighters and maste rcarpenters formed guilds.” [1, 3]

Medieval

The Early Medieval period feature a number of Naval clashes that made it to even the famously sparse Indic historical record. Featured as a frequent place for such boat-led battles.

“A sea-battle is talked about as having taken place in 610 A.D. at Puri (Gharapuri or Rajpuri?) between the Mauryas and the Chalukyas. A second sea-battle is referred to around Thane between the Konkan Silaharas and Kadambas. A third one, monumentalized at Eksar near Borivli by means of Viragals (herostone) is the last battle of the Silharas against the Yadavas. It brought to end the coastal Silhara rule in 1265 A.D.” [1, 4]

It should also be noted that Thane was the site of the first Arab caliphate invasion of Indian proper; however, this was defeated by the Chalukyas. “In the deep south, the Pallavas and later the Cholas built strong naval fleets and promoted sea-trade with the regions across the seas. The Pallavas and Cholas had sent naval fleets to Srilanka, Maldives and Lakshadweep (the Palaya-teevu) and even conquered Sandima Teevu (Old Goa). But the major achievement of Indian, sea-movement is the large naval expedition of Rajendra Chola to Srivijaya and Sailendra Kingdoms of Southeast Asia.” [1, 5]

Enterprising Indians first established mercantile guilds (sreni) that explored and established commercial outposts in South East Asia. Due to the presence of pirates and later piratical empires, Imperial Armadas would be sent to secure sea lines of communication as well as trade monopolies. Despite this competition between Indians and Indianised Kingdoms in South East Asia, these were typically resolved with token tributes and restoration of privileges (in contrast to the religious cruelty of the piratical portuguese and the artificial famines of the brutish empire). Imperialism may be the way of the world, but industrialised colonialism need not be. While one intermingled and respected local agency & autonomy, the other sought to stamp out whole religions and genocide whole populations.

Colonial

Naava Saasthra has long been understood to be the main stay of Indic Shipping. However, it has long been acknowledged to be lost. And here is no surprise to this, as the british destroyed Indian shipbuilding as actively as they destroyed the Indian textile Industry: “competition and all that, dear boy“.

However, it wasn’t the british empire, but the Pallava empire that first planted its flag on Lakshadweep. It is postulated that the Maratha empire militarised its presence on the Andaman & Nicobar island. It’s difficult to prove for sure as the british burnt the government house of Pune.

The Maratha Navy is admired by the Indian Navy today not because it was the first or even the most expansive, but due to the All-India and All-Indian Ocean orientation of its founder Shivaji. Indeed, the Delhi Turkics and mughals were hardly sea-empires and neglected this arm terribly (despite the piratical exploits of the Siddi of Janjeera). It was Shivaji Bhonsle who saw how the Portuguese implemented their ransom on Indian Ocean vessels, requiring a protection money pass called Cartaz. Imagine that, a non-Indian ocean country licensing Indian ocean vessels.

Seeing this, Chhathrapathi Shivaji challenged them and even the british through a litany of sea-worthy craft. Though the Vijayanagara Empire laid Burma and Sri Lanka to tribute through its powerful navy and massive maritime ships, the Maratha vessels were more modest but swift war-boats. They took the concept of the fast-moving Deccan Light Horse and applied it to the sea with deadly effect. Soon the Europeans (who had better boats and cannon) were hoisted by their own petard. The Maratha brown-water force soon became a blue water navy and established a military presence even as far as the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

“Early Tamil merchants knew them as Nakkavaram, while after the tenth century AD they were known to Persians and Arabs as the ‘Langabalus’. ” [1, 257]

It is for this reason that the Maratha Navy is so celebrated. It is easy to build big from a strong foundation, hard to start from scratch and challenge converging colonial powers and literally global thalassocracies. Even here, it was Nanasaheb Peshwa who betrayed the Angre Admirals, by teaming up with the British to destroy the Maratha stronghold of Vijaydurg, in 1756 CE. Once the victory was scored, the British ensured Indian shipbuilding would not rise again until V.O.C.Pillai (Tata & Wadia opium collaborators notwithstanding).

Modern

The Republic of India’s Navy remains a regionally powerful & internationally respected fleet, and is widely seen as a growing arm of a rising global power. Today it fields 150 ships & 300 aircraft. It is 75,000 strong with 2 aircraft carriers, 1 amphibious transport, 4 landing tanks, 13 destroyers, 15 frigates, 2 ssbns + 17 conventional submarines & 17 missile corvettes.

All of this is on top of a massive merchant marine and an explanding shipbuilding capability via Mazagon Docks Ltd & Cochin Shipyard, and so on.

Vessels

“Kautilya’s Arthasastra talks of seven types of water crafts. The Rajatarangani talks of a sea-voyage of a Kashmir prince to Srilanka. The process of hinduisation of islands of the Southeast Asian archipelago, especially Sumatra, java and Borneo seems to have taken place during this period, with an emigration of Brahmins as evidenced by the early Sanskrit inscriptions in those areas.” [1, 4′

Manufactury

Wood planks and joining material are critical inputs for any sea-worthy vessel.

Readers may recalled our article on Rasa Sastra, and how India specialised in developing natural chemical glues. Caulk is one such:

“Caulking is a vital process for keeping the adjoining planks firmly water-proof especially in the lower bottom, below water level, constantly under water. Caulking is done with help of a mixture in oil, who contents are secret among the main carpenters. Even if the caulking composition is understood, the exact proportion of each element in the mixture is never revealed and this caulking mixture varies regionally all along the Indian Coast.” [1, 81]

1 common mixture is lime, tree resin (kundarga), frankincense, groundnut oil, linseed oil, or neem oil. This is then heated over a flame to create a dark-coloured, high-viscosity fluid. This is then poured between planks of wood, on layers of coir, husk, or fibre. This effectively makes a leak-proof vessel.

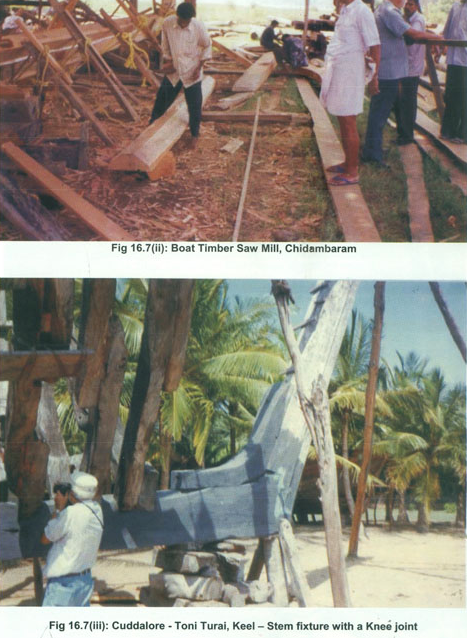

“The master carpenter looks for specific timber species for a particular boat component…He looks for the required specifications of length and girth as well as suitability for plank joinery by different methods. Freedom from physical structural defects of growth, especially in the segments intended for logging is an essential pre-requisite…Knots, knuckles, bores and cavities in the trunk, weak cut-sections and hollow heart are more difficult to trace. The Tamil palm leaf manuscript, Navoi Sattiram, has a couple of stanzas relating to Maram Vettu Vastu Sastra (the sequence of vastu or architecture, pertaining to tree felling forest for timber), and Marakala Muhurta (auspicious time for building boats) and Era Edukka (rules to lay the keel).” [1, 57]

“The nailed boats are of two major forms of build: either carvel or clinker. Carvel build has planks fitted edge to edge, flush with each other. Clinker build has the planks overlapping each other in a vertical direction. This build is also of two forms: the lower plank is fully exposed on the outer sidetouching the water, while the upper plank’s lower side overlaps the other on the inner side…The war boats of the Maratha Navy in the 17 and 18th centuries were mostly clinker built. The overlap of planks on above another prevents water spilling from lapping waves from entering into the boat.” [1, 82]

The manufactury of ships was therefore a mature and well-developed industry in the India old. Despite its peculiarities it produced a variety of categories & types of ocean and river going craft. These were then adapted to the specific local needs of Indian transport.

“Normally the timbers of ancient Indian ships were not nailed or riveted, but lashed together; this was done to avoid the imaginary danger of magnetic rocks, for the technique of nailing a ship’s timbers was certainly known in India in the medieval period. In fact sewn or lashed timbers were more resilient than nailed ones, and could stand up better to the fierce storms of the monsoon period and the many coral reefs of the Indian Ocean. ” [2, 227]

Categories

Sewn hulls, carvels, and 3 masted ships are very common from the Satavahana era onwards.

“The Periplus of the Erythrean Sea is perhaps the earliest western work which mentions some of the Indian boat forms. The Kotimba and the Trappaga are stated to being used in the Gujarat coast, especially the Gulf of Kambhat as pilot vessels. In the Southeast Tamilnadu coast, Kolandia and Sangara are mentioend as the crafts, but no further details are provided. Early Sanskrit texts tal of the nau, nauka, Navoi and Pota with anchors. The Yukti Kalpataru mentions Dirgha and the tall ship Unnata, with sub-classes like the Manthara, that is safe and strong, while the Urdva, the Garbhini, Suvarnamukhi, Anurdva are believed to have evil effects. Early Tamil Sangam literature mentions nearly 20 different types of water-crafts, but of them, Vankam Navoi, Marakalm are of the sea-going type,w hile the Ampi is coastal. The Kappal Sastram in Tamil carries technical details of building a boat plank by plank”. [1, 7]

The main categories of vessels are sewn, dugout, raft, lashed, nailed. These categories would have been recorded in painstaking detail in the typically pedantic texts of India. The Indian preference was for lashed or pegged boats. Nails were seen as easily corroding and unreliable. “Nailed boats must have come into vogue on Indian coast quite late. The wide prevalence of sewn or stitched boat forms for both coast and overseas voyages, irrespective of the size of the boat…nailed boats came into use only as late as the 12th century A.D….In fact, the early arrivals among the Portuguese boats on Indian shores were taken aback by the larger size-upto 600 tons—of the sewn boats built in India and employed in overseas cargo and passenger traffic. ” [1, 94]

Sewn

“The traditionally built timber vessels were mostly sewn or stitched over most of the West Coast, south of Bombay and the East Coast as far north as Lake Chilka. In Gujarat the boat planks were pinned together using Vadhera joints. It is only on Bengal Coast with a Southeast Asian tradition boats were nailed. Sewing holes are bored with hand drills at close distances close to the rims of the planks and the sewing twine is taken through them for fastening. A combination of pegging, use of wooden wedges and stitches enhances overall strength of the stitched hull, imparting it a quality of resilience that stands the vessel in grounding, crashes, and wreck.” [1. 64]

Sewn boats can be found throughout the Indian Ocean, but especially in coastal India, Persia, Arabia, Sri Lanka, and the East Coast of Africa. As with the dhow, discussion is rife as to who influenced whom. Jute fibre is used to sew these vessels together. For a 100 ton vessel, 50 tons of coir, fibre, and husk are needed to sew it together.[1, 77]

Dugout

“The dug-out is built by scooping out the wood, with the aid of adze, leaving the sides of a thickness of 10 to 15 cm, and a bottom or base that is somehwat thicker, about 20 cms. The top is opened out so that 2 to 4 men can sit within. ” [1, 69]

Mango is considered ideal for this type of vessel. Canoes of this kind can actually be rather large. The Choura Island Nicobar canoes are large enough for 20 men. Pseudo-dugouts can be made by covering planked or sewn boats with pitch (inside and out).

Outrigger

The next category of vessel is the outrigger (balance board). This is ideal for medium distances in shaky waters. The balance board provides ballast against choppy waters and reduces the likelihood of capsizing. “Today, outrigger boats are found on some stretches of the coasts of Sri Lanka, in the Gulf of Mannar, south of the Palk Strait, especially around Kilakkarai, and in a segment of hte west coast between Goa and Dabhol.” [1. 71]

Catamaran

“A distinctive type of raft, characteristic of a great part of the Eat coast of India, south of Lake Chilka in Orissa and a small part of Southern Kerala, south of Quilon is the Catamaran. The word is an anglicized corruption of the Tamil word Kattumaram, meaning a number of logs tied together. It is an extraordinary arche-type, ideally suited as surf-rider. ” [1, 24]

“The fishing community of the Coromandel coast are all HIndu mukkuvar and sembadavar. Their use of the catamarn type is not so much controlled by the surf environment as by the functionality of the type in relation to the specific fishing nets.Even discarded logs of old catamarns are refitted for use as rafts in backwater cast net fishing in shallow surfless waters.” [1, 31]

Types

The major types of vessel are raft, outrigger, carvel, and clinker. However, native approaches to shipping established native designs and forms.

The native designations for local craft may vary from region to region and indeed from age to age. The Yuktikalpataru of Bhojadeva describes 2 major divisions of boats, Saamaanya (ordinary) and Visesa (special). The former is for river boating and the latter are for seafaring.

He gives 10 types of Saamaanya boats, with their dimensions (converted here to feet): Ksudra (24x6x6), Madhyama (36), Bheema (60), Chapala (72), Patala (96), Bhaya (108), Dheergha (132), Pathraputa (144), Garbhara (168), and Manthara (180). The proportions were firstly 4:1:1 (LengthxWidthxDepth), but more typically 2:1:1.

Visesha vessels used iron foils, copper nails, and lodestones. They were subdivided into Dheergha and Unnatha: Dheerghika (48x6x4.8), Tarani (72), Lola (96), Gattwara (120), Gamini (144), Tari (169), Janghala (192), Plavini (216), Dharini (240), Vegini (264).

Unnatha Vessels were typically taller: Urdhva (48x24x24), Anurdhava (72), Svarnamukhi (96), Garbhini (120), and Manthara (144). Some of these were considered to be more fortunate than others. Some were deemed outright unsafe for navigation.

Paramaara Bhoja also identified masted vessels by colour: White (4 masted), Red (3 masted), Yellow (2), and Blue (1). Boats were known to carry everything from royal treasures to horses and royal family members. Sarvamandhira were for all of the above, Madhyamandhira for pleasure trips (cabin on middle), and Agramandhira for long voyages and naval warfare (cabin on prow). [1, 106-7]

Pleasure-boats were also known and relied upon by princes to woo their lady loves.

Regional Forms

Regional Boat forms come in a variety of names and types, too numerous to detail here. Nevertheless, we have provided some examples: The Gujarati nauri is deemed the equivalent of the Arab bhoom or dhangi. The Gujarati baggala is the equivalent of the Arab dhow. The kotia is a large, native 2 masted vessel. [1, 197]

The Konkani galbhat is a descendant of the famed Maratha ancestor, used to great effect against European colonial powers.

Tamil Nadu has one of the most robust collections of native boat forms. We will list them as follows:

Rafts & Floats: Maram, Teppam, Kattumaram (Catamaran), Mitappu, Punai, Mitavai.

Dug-outs and outriggers: Cankatam, Kulla-doni, Oruva, ZVattai or Vattal, Vallam, Parisal or Catti-toni.

Coasters and Lower river boats: Ampi, Toni, Podam, Pataku.

Seagoing vessels: Suluppu, Vankam, Kalam, Marakalam, Padagu, Doni, Kappal Sampan, Navoi Matalai. [1, 207] The largest of these are 50 to 300 tonnes, with keels of 50 feet. [1, 218]

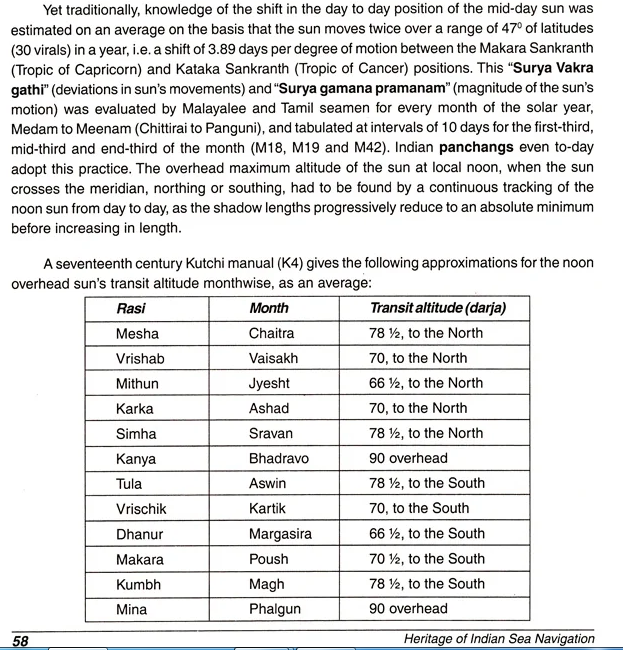

The Lakshadweep and Andamans also have their own distinct styles of vessels. However, for the sake of brevity, we will merely make reference to them.

Navigation

“Whether or not the Aaryans of the Rg Vedic period knew the sea, by the time of the Buddha hardy sailors had probably circumnavigated the sub-continent, and perhaps made the first contacts with Burma, Malaya and the islands of Indonesia.” [2, 226]

Ancient Indians were known for their ability to navigate via the stars and the monsoon winds. The field of study was a veritable science of its own, and the practical art of using the magnetic compass was known to Indic Civilization (matsya yantra). The placement of an iron fish in a bowl of oil was used to point to magnetic North. In tandem with star charts, this formed the basis of navigation.

The account of the seafarer Bodhisatva is particularly illuminating because it provides us with a sense of the Indic perspective of navigation and geographical orientation.

“He identified an area as Usamalin (wearing hoof garland) by recognizing a specific fish noted in abundance. An area farther away was noted as Dadhimalin because of it silver-bright, whitish appearance with foam, and yet another as Agnimalin because of its golden, yellow look. Still another sea segment was noted as Kusumalin (garland of Kusa grass) with the luster of sapphires and topazes and another as Nalamalin (red garland), close to the ‘edge’ of the ocean. The bodhisatva could identify the bottom sediments in different parts of the sea. L.P.Jaiswal in the journal of Bihar and Orissa Research Society identifies Dadhimalin with the Red Sea, Kusumalin with the Persian Gulf while other scholars identify Agnimalin with the Red Sea and the Dadhimalin with the luminescent and frequent fluorescent occurences in the open Arabian Sea. The Nalamalin at the end is identified by some with the Gulf of Khabhat” [1, 3]

The results speak for themselves. Indian merchants and seafarers left accounts and artefacts from Madagascar to Malaysia. Clearly the ban on sea-travel was more or less restricted to the top-most varna, with vaisyas and soodhras being comparatively more free to traverse and trade with the world. The robuts starcharts for navigation show an All-India approach. Indeed, this topic could be an article to itself.

“At this time Socotra had a considerable Indian colony, and the name of the island may be of Indian origin. Indian merchants were met by Dion Chrysostom in Alexandria. ” [2, 228]

Key Personalities

Vasishtiputra Satakarni

Narasimhavarman Pallava I

Silhara

Pulakesin Chalukya

Rajendra Chola

Krishnadeva Raya

Chhatrapathi Shivaji

Kanhoji Angre

Important Texts

Naava Sastra

Nauka Sastra

Artha Sastra

Kappal Sastram

Yukti Kalpataru

‘Our Hindu Navy’ by Pavgee (1931)

“A History of the Maratha Navy and merchant Ships’ by B.K.Apte (1973)

‘The Sailing Craft of India’ by L.Varadarajna (1987)

‘The Culture of the Catamarans’ by B.Arunachalam (1993)

Conclusion

“The oldest ship traces in the archaeological past was built about 6000 years before present. It is the funeral ship of the Egyuptian Pharaoh Cheops of the IV Dynasty. The watercraft was 133 feet long and 26 feet wide. Her bow and stern are curved upwards and are decorated with carvings of flowers of papyrus reeds. The technique of construction of this large ship is well advanced for the times. However the boat and its sails indicate that it was a riverboat of the Nile…The seaborne trade of Dilmun (modern Bahrain), Magan and Meluha with Sumeria indicate such a reed boat could sail upto the Indus valley. The boat, light in weight and with a shallow draught, could carry a large cargo.” [1, 16]

Getting a sense for the scale of Indic navigational achievements can often be a difficult task. On the one hand are the colonial and post-colonial narratives, which deprecate everything native in favour of the foreign. On the other hand, are the “astralaya” proponents who have the audacity to lecture on history (or any serious topic for that matter). This is the damage that serial motormouths (and the rewarding of such buffoons by an even more buffoonish citizenry) can do. In contrast, serious scholars (who have validated the theoretical through their own practicals) have adumbrated on the achievements of Indic seafarers.

“Thor Heyrdahl, in his work on the ‘Maldives Myster’ based on his investigations in the Maldives came to the conclusion that around 1500 BC, the Maldives people-hindus-were in contact with the last phase of Indus valley civilization across the tropical seas. He had visited Lothal and Bhagatrav on the Narmada estuary and found the same type of reed, bardi or Typha angustata, growing in plenty in the fresh water swamps of the estuaries.” [1, 16]

Indeed, the very origin of the Sinhalese culture is rooted in Indic seafaring from Eastern India.

“The Mahavansa of Srilanka mentions the voyages of Prince Vijaya and his 700 men in pre-Christian era to Srilanka from the ports of Bengal. The maritime traditions of Bengal appear to have continued over the centuries and the numerous folklores embodied in the works known as Padma Purana or Manasa Mangala Kavyas talk of many Bengali sea-voyages and shipwrecks.” [1, 247]

So integral to the culture is sea-faring to the East, that the people of Odisha have a beautiful festival called Bali Jatra, dedicated to the annual ship-voyage from Odisha to Bali, Indonesia.One can of course drone on and on, but in this age of drone warfare (both aerial and naval), perhaps it is best to conclude here for this introductory article.

Seafaring, since time immemorial has sparked imagination and fantasy. Such flights of fancy are what motivate men to travel halfway across the world, whether in search of wealth, adventure, or war over women.

References:

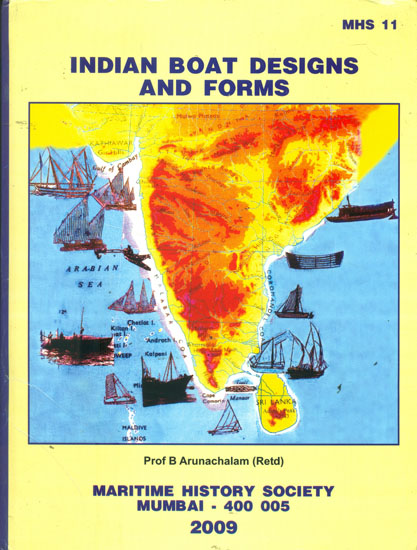

- Arunachalam, Prof B. (Retd). Indian Boat Designs and Forms. Maritime History Society. Mumbai. 2009

- Basham, A.L. The Wonder that was India. New Delhi: Rupa.1999

- History of Maratha Navy and Merchant Ships: https://msblc.maharashtra.gov.in/pdf/pdf/A%20history%20of%20the%20maratha%20navy%20and%20merchantships.pdf

- Majumdar, R.C. Ancient India.New Delh: MLBD. 2003