It is rare in history that a true vairagi emerges to lead with both courage and intelligence. One who is skilled in both combat and wisdom is the one who is truly fit to rule. However, one who has the character to sacrifice himself for the cause is the one who truly embodies Rajadharma.

In this stage (year 5119) of the Kali Yuga, such a figure is rare and revered. One such Personality, who was a larger-than-life personality, commanding respect across sampradayas and regions of Bhaaratavarsha, was verily named Banda Bairagi.

Our next installment in our Continuing Series on Sikh Dharma is Banda Bahadur Singh.

Background

mannai Dharam saytee san-banDh.

The faithful are firmly bound to the Dharma. (3-9)—Sri Guru Granth Sahib ji

A man as commanding and controversial as Banda Bahadur Singh ji would invariably come from a background with some minor controversy. The petty personalities of the present time often fight to assert claim over figures who through magnificence, are respected across parochial lines. There are a number of motivated accounts making even more untruthful claims. [2, xx] One regarding Banda Bahadur Singh ji was whether or not he had become a full Sikh or had remained a Hindu. And the answer is simple:

The founder of the first Sikh Raj was born a Dogra Rajput named Lachman Dev, and died an amritdhaari Sikh called Banda Bahadur Singh.

While details are sparse (including his date of birth, ~ 1670) [2, 6], he is known to have been born in Rajouri, Jammu to Ram Dev and was initiated into Sikh Dharma by Guru Gobind Singh at Nanded, Maharashtra. Though he thought to name him “Gurubaksh Singh”, the Tenth Guru anointed his Sikh officially as “Banda Singh Bahadur”. This is because the Leader of Sikhs himself had to become a Sikh. In a poetic twist of fate, this connection between Guru and Sishya was established when the two first met decades before, in a chance meeting. And thus we one must return to the land of Bahadur’s birth.

Lachman Dev grew up a quiet boy in the cold northern regions of India. As a Dogra Rajput from Jammu, he learnt shastar vidya at a young age. But in an era of foreign hegemony, when the Rajas themselves had been humbled, his father Ram Dev was a humble cultivator. Young Lachman had no interest in tilling the land. Though he was from Buttana (Rajauri), he spent time in Haripur as well. It is believed by many that Lachman Dev met Guru Gobind Singh in early adulthood, possibly even before he became a bairagi. All this would explain why Guru ji sought out Lachman in Nanded. Nevertheless, in the interim period, Banda was a committed athlete (though his build was more sinewy than stocky).

He had studied in a pial school (village school) taught by Pandit Dev Dutt. Despite being a bright student, he had no interest in ostentatious learning. Banda focused on athletic contests, and wrestling, but was famed as an archer. To this day, shikaar is a passtime of the rural residents of Jammu. But at this time, there was also the famous incident where Lachman lost all love for hunting.

He had gone out on shikaar with his cousin Mul Raj and came upon a female deer. When his arrow met his mark, he soon found out to his horror that the deer had been pregnant, and its progeny squirmed briefly in agony before passing. It was then and there that young Lachman was set on the path of a renunciate. Soon Swami Janki Prasad, a Vaishnav vairagi, took him under his wing and gave him deeksha. [1, 33] All this happened around 1685 CE.

By 1708, young Lachman Dev had become Swami Madho Das. He travelled throughout the trans-Himalayan tract with Swami Janki Prasad, and did pilgrimage throughout Kashmir. Having taken a vow of celibacy, he was now a bairagi. That is, he was one who had attained Vairagya (detachment) from the worldly concerns of the world. Having departed from Swami Janki Prasad, Swami Madho Das now established himself at Nanded as his own master, with his own chelas, at his own ashram.

As an ascetic, he was given the name “Madho Das” by his Vaishnav Guru, but he would soon be named something else. The Tenth Sikh Guru sought him out in the South, at Nanded (Maharashtra), when Madho Das was 38. “Before that fateful meeting, his allegiance had been to Vaishnavite and Sh[aiv]ite traditions. He was a natural fighter and hunter and…had studied religious texts, spirituality, and Tantra “.[1, 13] It is commonly known that some among Kashmiri Pandits had through practice of Kaulachara, attained occult powers. Madho Das was credited with having attained them. Some have taken liberties to say that he enjoyed using them to ridicule others.

It was a controversial crossing of paths. Knowing full well that Madho Das was a vegetarian vaishnavite, Guru Gobind Singh had two goats slaughtered nearby, and his followers soon partook of roasted mutton. Madho Das’ chela Nitya Nand informed him of what happened. While some believe he then used his occult powers, they had no effect on the spiritually enlightened Tenth Guru. Guru Gobind then smiled, and gave his apologies for his followers slaughtering goats in a place of sanctity, and asked for purificatory rites to be performed by Madho Das himself. He then said:

“I respect you for the concern that you have for all forms of life and I can feel the pain that you feel at the killing of these goats. But tell me, do you feel no pain at the killing of thousands and thousands of people who have been victims of Mughal tyranny through all these long years?” [1, 39]

And with that, Tenth Guru soon had gained his greatest follower, who now called himself his ‘Banda’. The bairagi was now attending the Sangat of the Sikhs, learning not only about the Khalsa and its maryada, but also the nature of the enemy they faced, and what had to be done to succeed against it. The importance of having both worldly sense and spiritual sense was inculcated in all. He also lectured on how varna vyavastha had been misused, and dharma corrupted by changes such as the zamindari system (which was used by the Mughals and their chamchas to oppress the common man). To restore true Dharma, force of arms would be required (and Bhai Binod retrained Madho Das in archery, and taught him the Military History of the Sikhs).

Finally, Guru taught Banda Bahadur a key change in battle tactics, which incidentally, the Marathas had used to successful effect (and one learned from the enemy itself):

“There was no shame, in abandoning a battle as a war was rarely made of a single battle, but was almost always a series of battles. Only when there was a no hope of another battle must they continue to fight against overwhelming odds to the very end and die as martyrs to the cause and thus serve as an inspiration to the generations to come.” [1, 44]

“Banda Singh Bahadur is among the most colourful and fascinating characters in Sikh history. From an ascetic he was transformed into Guru Gobind Singh’s most trusted disciple. So much so that when the seriously injured guru could not lead his Sikh army against the Mughal forces, he appointed Banda Singh Bahadur as his deputy. As proof of this appointment he gave Banda his sword, a mighty bow, arrows from his own quiver, his battle standard and his war drum.” [1]

Banda would need all this very soon. When Guru Gobind Singh had been attacked by two Pathan assassins (likely at the behest of Bahadur Shah or Wazir Khan), the wounds (though treated…curiously by an Englishman) would prove mortal. English physicians had an odd way of turning up at the exact wrong time, among not only the Marathas, but even the Mughals, and Sikhs. This, despite the advanced state of Indian Medicine. The wound was poorly sutured, and while some claim it was the Guru’s love of bows (despite medical stipulation for rest) that caused the wound to reopen, other possibilities should be considered as well. Regardless, the Guru had given Banda a series of commands, including the need to take the advice of the Panj Pyaare, and most importantly, gave him amrit:

“Sugar crystals were added to water in an iron cauldron and the water was stirred with a sword to the reciting of prayers till the sugar dissolved. The guru gave this amrit, nectar, to Madho Das to drink. ‘I give you the name of Gurbaksh Singh.It is an apt name because you are indeed, for me, a bakshish, a reward from God. But in my heart I will always think of you with the name that you gave yourself, Banda. May you always be my Banda Singh Bahadur.” [1, 21]

Finally, Guru Gobind Singh led his newest Sikh in recitiation (jap) of Japji Sahib (morning prayer of the Sikhs). With that, Banda Bahadur Singh was off.

“He attempted an arduous punishing journey of some 2,500 kilometres, with no training, no weapons, no army…Yet, in 20 months, Banda Singh Bahadur captured Sirhind and established the Khalsa Raj…His deeds were that of a mortal, legendary accomplishments not rhetorical or magical. he prepared the coming generations of Sikhs for future conflicts: Sikhs warring with Afghans, Persians the Mughal empire.‘” [1,13-14]

Against heavy odds, Banda and 25 Sikhs split up into small detachments to avoid drawing suspicion. They reconvened at pre-determined points (in Rajasthan and Punjab), and finally linked up at Bharatpur. Along the way, they had been given news of the passing of Tenth Guru, and their finances had also dried up. A total of 31 Sikhs now remained directionless, and unsure of where even their next meal would come from. At that point a stranger named Sant Singh (a Lubana Sikh) approached and gave his dasvand. After testing him for good faith, Banda Bahadur gladly accepted, and began a campaign to build confidence among the poor and oppressed (irrespective of caste or creed) in the Sikh cause. [2, 22]

His first move was to crush a dacoit gang led by Randhir Singh, raiding Bangar villages. Like the cinematic Seven Samurai, the Sikhs of Banda ambushed the dacoits and defeated them. Suddenly his ranks swelled with volunteers. Unable to give regular pay, he promised a share of the booty taken from the dacoits.

From there, he set his sights on Sadhaura, Malerkotla, Samana, Saharanpur, Panipat, Jalalabad, and above all, Sirhind. Sirhind was where the wicked Wazir Khan resided. This dusht had cruelly bricked alive the two younger sons of Guru Gobind Singh, for refusing to convert. With the Mughal occupied in the Dakshinapatha, the conditions were ripe for Banda to strike. But being a bairagi, he was wise. He did not let the thirst for vengeance against Wazir and his wazir, drive his decision-making. After consulting with the Panj Pyaare, he took stock of the situation and his force strength.

Only 1,500 men were core committed regulars (with only 500 horse). Another thousand or so were mercenaries under Ram and Trilok Singh, who were middling in loyalty. Lastly, there were assorted free-booters who were less interested in the cause, and more interested in profit. Therefore, Banda first ensured he had a strong intelligence network, and good logistic supply from Banjaras and other gypsies. Aiming at minor victories, he would challenge the regime’s image in the minds of the populace. They would start from the periphery then head to the core. With that strategy, and with a force of 4,000 soldiers, he aimed for Samana.

Battle of Samana

Samana was said to have been founded in the 12th century by the Samanand family. It was a town south west of Patiala. It was very wealthy, but exploited the peasantry. As such, the average man and woman hated the ruling elite.

“there was no governance in Samana, no concern for the welfare of the people, no civic pride. There was only, among the rich and powerful, self-centred effort to be even more rich and powerful.” [1, 70]

Despite all this, it was surrounded by a strong wall, and each haveli was a well-supplied mini-fort. Against these difficult odds, it was decided that the wall would be scaled, and the attack would first be concentrated on Sayyad Jalaluddin. Once his fort was captured, there would be height advantage against all the other havelis.

Banda was also fortunate in that reinforcements arrived. Mali and Ali Singh had been in the service of Wazir Khan, but were disgruntled and joined with Banda.Others included Fateh Singh (descendant of Bhai Bhagu), as well as Karam Singh and Dharam Singh.

On the night of November 25, 1709, the attack began, and by sunset of the 26th, the battle was over. So much did had the common populace groaned under this oppression, that it is said to have risen up and slaughtered their overthrown rulers, sparing no one. Man and woman had both treated the population cruelly, and Banda could do nothing to hold the mob at bay, lest he and his army too be targeted. That is the danger of vengeance, for once the spark is ignited it is difficult to tend the fire. To placate the mob, Banda held quick trials and executions of the ringleaders of the rulers. This was a war to punish the wicked.

He then divvied up the booty, and saved the rest for his treasury. He credited Bhai Fateh Singh’s bravery with distinction and gave him command of Samana. Other administrators were also appointed, with 3 of the 5 coming from scheduled castes. Langar was established, and all men, irrespective of caste or creed, sat together in common meals. [1, 80]

Battle of Sadhaura

From Samana, numerous victories followed. Guram, Thaskar, Thanesar, Shahbad, and Mustafabad were all besieged and captured. As the rulers of Thaskar and Thanesar had been kind and just, they avoided pillage and bloodshed. The same could not be said for the others, which had a ruling elite like Samana’s. Banda then set his sights on Sadhaura. Sant Singh’s relatives give him aid and rest at the town of Kapoori. Saudhaura was targeted not just because it groaned under a greedy elite, but because it had a reputation for religious intolerance. Hindus were not permitted even the right to cremate their dead, and coerced conversion was rampant. The city was ripe for overthrow.

Banda Bahadur’s order-of-battle now was 8,000 foot and 1,500 mounted. But Sadhaura’s fortifications were strong and well-guarded, by Osman Khan’s crack Mughal cavalry of 1,500, and equal number of foot. Banda decided to use the vast plain of peasantry, eager for justice, to swarm the 8 towers that guarded the fortress town. Realising he might be eventually overwhelmed by the peasantry, Osman decided to ride out. Though the casualties were numerous among the peasantry, Banda had prepared for this eventuality. He kept his best troops in reserve, and had them strike at his signal. Osman Khan soon fell, and the scales tipped in favour of the Sikhs. What followed was sheer butchery. The common man’s quest for vengeance could not be gainsaid. “The entire city was [razed] to the ground.” [1, 101]

Battle of Sirhind

Sirhind was second only in importance to Lahore. But the faujdar, Wazir Khan, had become insolent, and did not follow the orders of the subah (province) governor at Lahore. Thus, Sirhind became the real seat of Mughal power in the Land of Five Rivers (Pancha Naada).

“Wazir Khan, taking his cue from the bigotry of Aurangzeb, launched a policy of discrimination against the non-Muslims and subjected them to acts of great cruelty and barbarism, a policy which reached its peak in the martyrdom of Guru Gobind Singh’s two young sons in 1704.” [1, 109]

Crossing of Ropar

Advised by the traitor Suchanand, neither unmarried nor married women were respected by Wazir Khan, and rapine and plunder were rampant. As such, contact was first made with the enemy at the crossing of Ropar. Here, Sher Khan decided to ride out against the Majhaili Sikhs. Banda noticed this, and attacked, squeezing the Mughal contingent between the two forces. Though the Mughals had artillery, numbers, and Pathan reinforcements, a dust storm made visibility difficult. Using this advantage, the Sikhs struck the next morning, and the engagement was won. Banda then captured Banur and Ropar, and finally faced Sirhind.

At the critical battle of Sirhind, Banda divided up his army into jathas (battalions). Interestingly, each jatha was based on some form of solidarity (tribe or caste), to boost internal cohesion and loyalty. Though Suchanand had sent his nephew to infiltrate Sikh ranks, Bhai Binod Singh used the nephew for disinformation instead. Banda had 35,000 troops (though 11,000 were mercenaries or free-booters). Wazir Khan had 15,000 disciplined soldiers.

“The final measure suggested by Suchanand showed the level of cynicism to which he had allowed himself to sink. He, a twice-born Brahmin, advised the faujdar to call upon the mullahs to declare a holy war.” [1, 114]

To date, it hadn’t been a religious war, but the ruling elite’s policies now made it one.

Battle of Chappar Chiri

Wazir Khan rode out to meet Banda at Chappar Chiri, which was 10 miles from Sirhind. Armed with cannon (arranged in a semi-circled), he was well-prepared against the Sikh army. Banda called a council of war and it was decided to place the bulk of the reserves behind the hills. Banda would serve as general from there, and ride down only at last resort. The battle began on May 1710.

Artillery proved to be devastating against the Sikh jathas. Though their morale was high, it was flesh and bone against gunpowder and iron. Raj Singh soon informed Banda that the free-booters did not joined the fight, and men were losing heart. It was then that Banda Bahadur rode out through cannon. Fateh Singh and the Malwa Sikhs rode with him, and Bhai Fateh eventually fought a duel with Wazir Khan and killed him. The Chaar Sahibzaade had been avenged.

Using diversionary tactics, Banda’s army was able to mount the walls of Sirhind. Mob vengeance began again. The traitor Suchanand was captured, and gorily put to death, along with his son. Justice had been served. Those who had misused power and position would not be spared.

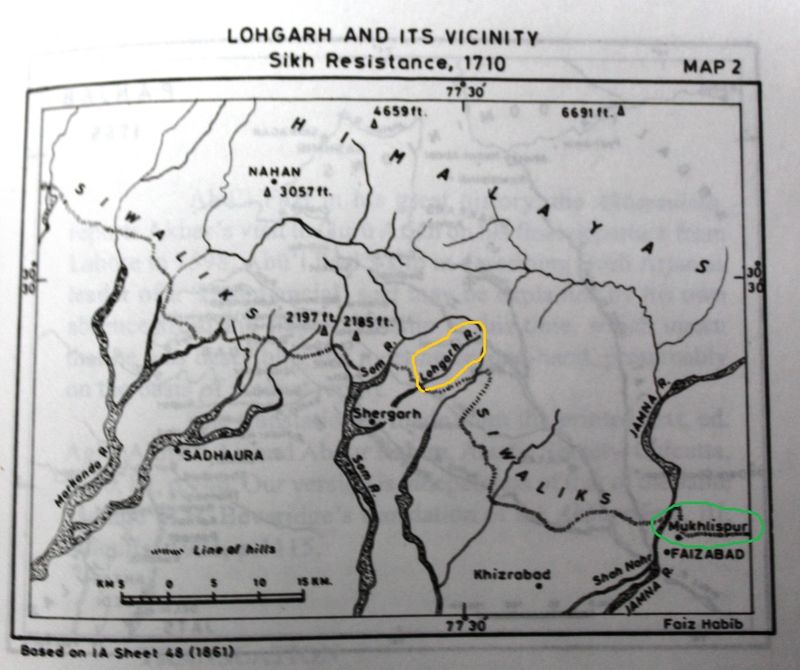

“There is no greater excitement than that which accompanies the birth of a state and if the capital of the state is also born at the same time, all the excitement focuses on the new town. So it was with Lohgarh. The entire region was gripped by a raging fever. After centuries of rule by foreign invaders, the natives had at last come into their own. ” [1, 131]

Battle of Lohgarh

After, Sirhind, Banda’s hand was strong. Bahadur Shah had moved from the Deccan to Rajasthan, facing an insurgency there. Capitalising on the situation, Banda captured Saharanpur, several other cities. The area between the Jhelum and Jamuna was now under his sovereignty. Only Delhi itself remained. He established an effective administration, and the aam admi of all castes and creeds rejoiced in his rule.

The overgrown landholdings of the zamindars were confiscated and distributed among the peasantry. Zamindars themselves were dismissed, and new revenue collectors were appointed, using the batai system of revenue (2:1, tiller: state). [1, 139] He then built his capital at Mukhlispur, and renamed it Lohgarh (in honour of the Tenth Guru’s fort). It was renovated, given an armoury, granary, stables, treasury, and arsenal. Despite being strategically well-placed, it would have to face the full might of the Mughals. Aware of this, Banda began training his soldiers. Coins were struck in the name of Guru Nanak Dev and Guru Gobind Singh:

Sikka Zad Bar Har Do Alam Fazl Sachcha

Sahib Ast Fath-i-Gur Gobind Singh

Shah-i-Shahan Tegh-i-Nanak Wahib Ast

Coin struck for the two worlds [spiritual and secular]

with the grace of the true lord, Nanak, the provider

And the victory of the sword [power] of Guru Gobind Singh, King of Kings, and the true Emperor. [1, 154]

As for the nature of the rule, it is clear in the seal of his Hukumnamahs:

Degh, O Tegh O Fateh O Nusrat Bedrang.

Yaft az Nanak Guru Gobind Singh

By the blessings of Guru Nanak and Guru Gobind Singh achieved the victory over the enemy and started ever giving, charity for the poor. [1, 155]

Though he never called himself Guru or King, Banda Bahadur Singh was now to become a king in all but name. However, all this was not to last. Though strategically placed, it would be difficult to outlast the resources of an entire empire, without reinforcements. Delhi itself was now under threat, and Bahadur Shah was forced to march against Banda Bahadur.

The Mughal had offered favourable terms to the Rajput Insurgency of Raja Amar Singh. As a result, Delhi could turn its full attention on Banda Bahadur. Bahadur Shah also received reinforcements from Raja Chatrasal of Bundela. The first engagement was at Thanesar. Bhai Binod Singh made a stand at Amingarh, in a thick grove. Though this neutralised the Mughal cavalry advantage, greater numbers soon overwhelmed the Sikhs, and they fell back in orderly retreat (first to Thanesar, then Sadhaura). Meanwhile the governor of Jammu had his army march on Sirhind in a surprise attack. While the Sikhs under Subha Singh rode out, morale dimmed when he fell to a stray bullet. Though they retreated to the fort, they soon realised they did not have numbers to hold out and vacated in the night.

On December 4th, the Mughal caught up with his advance force, and now prepared to march on Banda Bahadur at Mukhlispur. Though the Sikhs held their ground at Sadhaura, they were vastly outnumbered (with Imperial forces growing by the day). Banda then called a war council. They realised the Sikhs would be defeated at Lohgarh, so he sought the advice of the Panj Pyaare. The Mughals had 60,000 well-supplied, while the Sikhs had less than 15,000. The Mughal himself had ordered that Banda be caught or killed. Realising the importance of the bairagi to the cause, the Sikhs decided to have Banda escape. An imposter was put in his place and garb to fool the Mughals into thinking the “King of the Sikhs” remained at the fort. This noble Gulab Singh was soon martyred, and Banda made his escape with his companions. [1, 191]

Himalayan Politics & an Alliance

In a bit of a home-coming, the once-upon-a-time Lachman Dev returned to the land of his birth. The Himalayas were the place he long called home, and he soon found himself embroiled once more in Hill Raja politics.

While Bahadur Shah was said to have been losing his wits by the day upon discovery of Banda’s escape, the sacha Bahadur was now off to punish the Hill Rajas. Part of his mandate from Guru Gobind Singh was to punish not just the invader but the tyrannical. The debauched rajas of the region had too long been minions of the Mughals. Banda sent hukumnamahs for the Sikhs to assemble at Kiratpur. From there his army marched. The Raja of Sirmur (Nahan) was a friend of Guru Gobind Singh, and his son Bhup Prakash had been executed by the Mughal, as the Raja Hari Prakash permitted Banda to excape through his territory. [1, 207]

On the other end, was Raja Bhim Chand of Kahlur (Bilaspur), the worst of the Hill Rajas. He had behaved treacherously towards Tenth Guru. The Raja of Mandi was another such. Both had failed in Rajadharma, and both were defeated. While the former was killed, the latter was reinstated after he sued for peace. Other recalcitrant Rajas joined in submission, and promised support. They had all forgotten that Raja existed for Praja, and not the other way around.

The last Raja was Uday Singh of Chamba. Though he never showed hostility to the Sikhs, he never showed submission either. Banda marched to the outskirts of his territory. Uday Singh sent his Pradhan Mantri to inquire about their purpose. When Banda explained it was peaceful, Uday Singh welcomed him with open arms. Raja Uday had been known to be just to his prajas. Though Banda did not style himself as king, the Raja saw him as one. Soon Uday offered the hand of his niece, Rajkumari Sushil Kaur, in marriage.

Banda was in a quandary. He had been a bairagi his whole life. Although some Sikhs maintain Guru Gobind Singh had stipulated celibacy for him, it is also known that the Sikh maryada insisted upon grhastashrama (or the life of a householder). He soon turned to Bhai Binod Singh and the Panj Pyaares.

“In the early historical accounts compiled by the Sikhs like Rattan Singh Bhangu and Giani Gian Singh, we do not find any mention of the Guru’s command to Banda to remain celibate.” [2, xi]

So they decided that since Banda was now a Sikh, and the friendly Raja could turn hostile if his generous gesture were rejected, that the “King of the Sikhs” had to be married. Now secured with the alliance of the Raja of Chamba, and the submission of the other Rajas, Banda was now well-equipped to resume raiding Mughal territory. Batala was the first. [1, 219]

Bahadur Shah had now died of dementia, but he had ordered “that all Sikhs be considered as pagans be exterminated“. [1, 231] Though his son was soon crowned, the latter was soon deposed and executed in 1713 by Farukhsiyar (through support of the Sayyid brothers). Meanwhile, the Sikhs were now in the verge of striking Lahore. But as with Delhi, a few years back, they were unsure about holding it.

Banda instead recaptured Sadhaura and Lohgarh. Lost gains were soon recouped. But the new Mughal had his sights focused on Banda, and did not spare Sikhs (civilian and soldier alike). “Thousands of Sikhs were killed, their heads strung together and hung on the gates of the towns. Those who survived abandoned the towns and once again sought the safety of the hills or of remote villages.” [1, 232] The noose was now tightening around Banda. Samad Khan, governor of Lahore, had been threatened with dire consequences if he failed. He rushed to Lohgarh. Realising a stand here would be futile, the Sikhs again escabled to Jammu, in the winter of 1713. [1, 233]

Near the Chenab River, Banda Bahadur made camp with his wife, and loyal Sikhs. Mata Sushil Kaur had now given birth, and his son Ajay was now growing up.

“He led a simple, spartan life and had no desire for material possession, for rich clothing and food”. [1, 252]

Like his father, Banda now began to till the land, and his companions soon reverted to prior occupations, from artisans to shopkeepers to entertainers. It is said that Mata Sushil Kaur had a difficult birth, and because a second child was no longer possible, Banda was asked to take a second wife. After much argument, he finally “married Sahib Kaur, daughter of Sri Chand, a Khatri of Wazirabad.” [1, 254] She would soon be pregnant with his second son, Ranjit Singh.

Finally in April of 1714, Sardar Jagat Singh defeated the Pathans of Khanuwan. Atrocities against the Sikhs had been so great, that many rose up in fury, and began hitting back at Mughal minions. 7,000 Sikhs marched on Sirhind, and they inflicted many casualties before orderly retreat. And so, Banda decided to ride out once again. Mata Sushil insisted on riding with him, along with young Ajay. This would prove to be fatal.

Battle of Gurdas Nangal

Banda marched to Kalanaur. Despite the faujdar declaring holy war, the religious zealots were defeated and put to the sword. However, Banda spared the civilian population. Colossal landholdings were again shared among the peasantry, allowing them once more the pleasure of dharmic and dignified labour. Batala too was also retaken. Bhatti Rajputs outside the forest of Lahore had also risen up. But Samad Khan managed to crush them. A number of armies soon convened at Lahore in 1715, with reinforcements again from the Bundelas. Realising the net that was being stitched, Banda decided to hastily build a fort at Kot Mirza Jan. Unfortunately, when it was half completed, the Mughals attacked with all their might.

An orderly retreat was then made to Gurdaspur. Though at first it appeared to be an ideal ground for a stand, it was soon surrounded not only by enemy soldiers, but also a downpour of water. It would be difficult to make an escape now. The siege of Gurdas Nangal carried on for 8 months (just as at Anandpur). But only 800 Sikhs faced 30,000 Mughal soldiers, with numerous cavalry and canon. It was a hopeless battle. It was then decided that Bhai Binod Singh would make a dash to safety, so that the Khalsa Cause could live to fight another day. His sorties had inflicted many casualties, with Sikhs inside the fort firing their matchlocks. Now Binod Singh would make his escape.

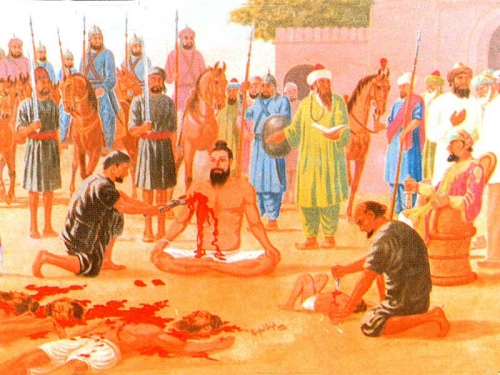

Some hold that Banda knew full well he now faced a tragic end, while others assert he had been given an offer of safe passage if he did not hold out to the bitter end. Regardless, what followed afterward was sheer barbarity. His entire party was arrested and humiliated in irons. Mata Sushil Kaur killed herself with a knife, to avoid dishonour. [3] One by one, Banda’s companions were tortured to death.

There is nothing to indicate Banda Bahadur met or was an aficionado of Bulleh Shah, though some sufi sympathetic writers have fantasised this. Nevertheless, a poetic life, deserves a poetic epitaph. As such, we turn East, where Rabindranath Tagore himself eulogised Banda in his native Bengali, below. Banda Bahadur was born in Jammu, lived as a bairagi in Maharashtra, and fought to liberate the Punjab—but he inspires a civilization to this day. Om Shanthi.

Pancha nadir tirey

Beni pakaiya shirey

Dekhite dekhite Guru mantre

Jagiya uthhechhe Sikh

Nirmam, nirbhik.

Hajar konthe Gurujir Joy

Dhoniya tulechhey dik

Nutan jagiya Sikh

Nutan ushaar Surjer paane

Chahilo nirnimikh…

Sabha holo nistabdha

Banda’r deho chhinrilo ghaatak

Shanraashi koriya dagdha

Sthir hoey Bir morilo

Na kori ekti katar shabda.

Darshak-jan mudilo nayan

Sabha holo nistabdha. [Partial Translation]

§

The Mughals and Sikhs together kicked up

the dust of Delhi thoroughfares;

Who will offer his life first?

There was a rush to settle this;

In the morning hundreds of heroes

offered heads to the executioner, calling “Glory be to Guruji”;

The Kazi put into Banda’s lap one of his sons;

Said…must kill him with own hands;

Without hesitation, saying nothing,

slowly Banda pulled the child on his breast;

Then slowly drawing the knife from the belt, looking at the boy’s

face, whispered

“Glory be to Guruji”, in the boy’s ears.

The young face beamed;

The court room shook as the boy sang,

“Glory be to Guruji”;

Banda then threw the left arm around his neck

and with the right plunged the knife into the boy’s breast;

The boy dropped to the ground, smiling, saying “Glory be to Guruji”.

The court was dead silent.

The executioner tore apart Banda’s body

with a pair of red-hot tongs;

Standing still the hero died;

not uttering a sound of agony;

The audience closed their eyes;

The court was dead silent [1, 7]

Achievements

- Led the Sikh Rebellion of 1709-1716 CE

- Established the First Sikh Raj’s capital at Lohgarh (Mukhlispur)

- Minted Coins in the Name of Guru Naanak Dev and Guru Gobind Singh.

- Liberated half the Punjab, and threatened Delhi itself with Siege

- Administered numerous cities with justice and good governance

- Brought villains such as Wazir Khan and his wazir to justice

- Punished recalcitrant Rajas and allied with just Rajas

Banda Bahadur Singh raised a Sikh Army virtually from scratch. Given Guru Gobind Singh’s blessings and insignia, he marched forth from Maharashtra and sought to Liberate the Land of the Five Rivers. While some hold that he had been given Five Commands from the Guru, it is known that the condition of celibacy did not appear in early Sikh histories. [2, xx] It is also thought that Farukhsiyar forged or forced the letter written by Mata Sundari, to ensure dissension in Sikh ranks. Banda’s success, however brief, becomes all the more impressive given the odds he faced, and was likely undone by bheda.

The Mughal empire had been ground down and defeated by the Marathas, with a tenuous peace signed in 1707, establishing Maratha independence; however, all of Northern India was still in Mughal hands. Against these resources, Banda Bahadur Singh and Sikhs faced terrifying odds. Alliances were tenuous and political support even more so. But he accomplished magnificent victories agains the Mughal power, and gave a stern reminder that the wicked would be brough to justice—however long it took.

Above all, he gave expression to the dream of the Sikh Gurus, and raised the banner of Guru Gobind Singh’s Khalsa.

Banda Bahadur’s most impressive achievement is in fact the summation of his legacy:

“He prepared the coming generations of Sikhs for future conflicts, which later greatly helped Maharaja Ranjit Singh in creating an empire of the Sikhs” [1]

Legacy

“Banda Singh Bahadur appeared in Sikh history for a relatively short period (1708-1716) but, after the Sikh gurus, influenced it more significantly than any other inndividual.” [1]

Born as Vaishnav Hindu Lachman Dev, he is beloved as Baba Banda Bahadur Singh by the Sikhs and attained martyrdom as one. He was given amrit & “baptised” into Sikh Dharma by none other than the very master of Sastra and Suhstra known as Gobind Singh. The Tenth Guru of the Sikhs was in a sense his first Guru as well as his last, having encouraged Banda as an adolescent in archery and having given him command of the Khalsa Army as a man.

His life was an embodiment of how to remake society. Bharatavarsha as a culture and civilization had declined from the great examples of Bhagvan Ram, Dharmraj Yuddhisthir, and the great Rishis of yore. It took a Rajarishi like Banda Bahadur, “King of the Sikhs”, to revive the ideals of Rajadharm. At a time when Vijayanagara and the Andhra Nayaks had long fallen, Maharana Pratap had passed, and Sambhaji Raje had been martyred, the great Banda Singh Bahadur revived the spirit of Rajadharma.

He sought to expunge wickedness both within the Bharatiya Samaaj and without. He brought the wicked Wazir Shah (and his wazir Suchanand) to justice, hammered recalcitrant Rajas who prioritised pride & debauchery, and was the terrible thorn in the side of the Mughal invaders. Delhi itself was within reach of this son of Jammu.

And yet, history took another turn. Banda Bairagi has long been critiqued by all, when in reality, the fault is within ourselves. Some Hindus say Banda never took amrit (when he in fact did, and had to in order to lead the Army of Tenth Guru). Some Sikhs say Banda himself “grew arrogant” and sought to set himself up as Guru (but there is no indication of that). And finally, others blame him for not abiding by the letter of Mata Sundari (Wife of Guru Gobind Singh). But as time has again and again proven the Gullibility of Indians, how many stopped to asked whether Farukh Siyar forged the letter or forced its composition? This was a time-tested tactic used by Mughals, and Turks. It was used successfully by the Afghan Sher Shah Sur when he faced a superior and more numerous Army from the Rajput Confederacy.

Thus, Banda Bahadur’s life is living proof that, “To remake society, we have to remake ourselves.” [4, 10] How many failed to respond to Banda’s call-to-arms? How many Rajas refused to ally with him? How many rejected giving him the benefit of the doubt?

But as Banda himself proved, “The sources of human happiness and social cooperation are not exactly the same as those of scientific inquiry. For the proper adjustment of man to the new world, and education of human spirit is essential.” [4, 10] Who better than a bairagi and “Banda” of the Tenth Guru to teach modern Indians by example.

Rather than external collaboration, we need internal collaboration. The “various aspects of the whole universe work in co-operation in order to maintain its integrated harmony and unity, rather than enter into conflict with one another, resulting in disintegration of the whole. These parts help each other to sustain themselves mutually..without human community there is no responsibility of the individual, and without such responsibility, without true morality in purely human sense, no human community can maintain itself.” [4, 11]

“That is why Indian thinkers have emphasized holistic philosophies rather than taking partial view of world…Dharma stands for that principle, that law, that order, which keeps up unity, harmony and solidarity of all created objects….Dharma is the very foundation of this universe (dharmo’sya Vis’vasya ‘ jagatah pratishta“. [4, 11]

While Dharma was strong in the ranks of Banda’s Army, the faithless were few, and the rank-and-file was fired up with the spirit of Tenth Guru. But when Dharma had declined, due to unwillingness to face the atrocities of Mughals, preference for life of comfort, Banda was betrayed and his cause ill-fated. The symptoms arose again after the passing of Ranjit. Why did the Mighty Sikh Empire fall in 1849? True, there were traitors, and British subversion, but there was also Rani Jindan and the incessant politicking within the ranks of Ranjit Singh’s appointed Sardars. The ambition of Nau Nihal, Sher Singh, Rani Chand Kaur, and the Sandhanwalias had sped up the unwinding of the empire. [5, 120]

It is this human penchant for pettiness that has undone dharmic rajyas time and again, and is the greater lesson in not only the loss of Lahore, but the downfall of the first Sikh Raj, the Maratha Samraaj, and the Rajput Confederacy, and many other Dharmic polities in the past thousand years. It is time for those who follow Dharma to learn this lesson of Rta. Indeed, the stakes now are higher than ever before.

As Parminder Kaur wrote in Sikhism In the Context of Indian Spiritual Tradition, “We are passing through a phase where we as a nation and world on the whole are on the brink of destruction. Violence in all forms is rampant in every nook and corner of today’s world. Modern war technology seems to threaten total annihilation of mankind. Taking into consideration our own country, we find collosal loss of sense of moral values. Divisive tendencies, regionalism, inter religious collisions are daily affairs. It is imperative therefore that we must find a way out to redeem ourselves from a situation like this. It is high time that we remind ourselves of our ancient wisdom and heritage which give relief and peace to mankind.” [4, 5]

Baba Banda Singh Bahadur was once such giver of relief to Bharat. He punished the unjust, scourged the wicked, and protected the innocent and weak. But it is best to summarise the life of this meteoric man in his own words:

“I will tell you, whenever men become so corrupt and wicked as to relinquish the path of equity and to abandon themselves to all kinds of excesses, then the Providence never fails to raise up a scourge like me to chastise a race so depraved; When the tyrants oppress their subjects to the limit, then God sends men like me

on this earth to mete out his punishment to them.” ~ Banda Singh Bahadur

References:

- Dhillon, Harish. First Raj of the Sikhs—The Life and Times of Banda Singh Bahadur. New Delhi: Saurabh Printers. 2013

- Singh, Sobhan. Life & Exploits of Banda Singh Bahadur. Patiala: Punjabi University. 2000

- Dhan Dhan Banda Bahadur Singh. http://www.bandasinghbahadur.org/vanshawali.php

- Kaur, Parminder. Sikhism In the Context of Indian Spiritual Tradition. Patiala: Gracious Boks. 2009

- Grewal, J.S. The Sikhs of the Punjab.Cambridge. 2017